As the climate crisis mounts, British Columbia is moving to promote use of electricity over oil and gas in cars and homes. But if electrification is the future of the province, it also is the past. During the expansionist boom times of the mid-20th century, dams rose as monuments to industrial progress under the banner of BC Hydro, the new crown corporation forged for the job.

Now the utility is constructing a new dam in Peace region, and Site C’s big cost overruns are well known. Less understood is how Site C extends a pattern in B.C. of colonial destruction, logging and flooding Indigenous territory without consent.

The climate emergency could, in fact, present a greater opportunity for First Nations to expand their production of renewable energy, selling their own-generated power across B.C. But the province, having bet big on Site C, has all but closed the door to such aspirations. Not that First Nations are giving up trying.

Today begins a two-part series that tells the story of how B.C.’s electricity system dispossessed First Nations, and how an Indigenous-led movement is working to wrest power back. At stake, they say, is nothing less than a sustainable energy grid that atones for the land it’s built upon.

‘The power trench’

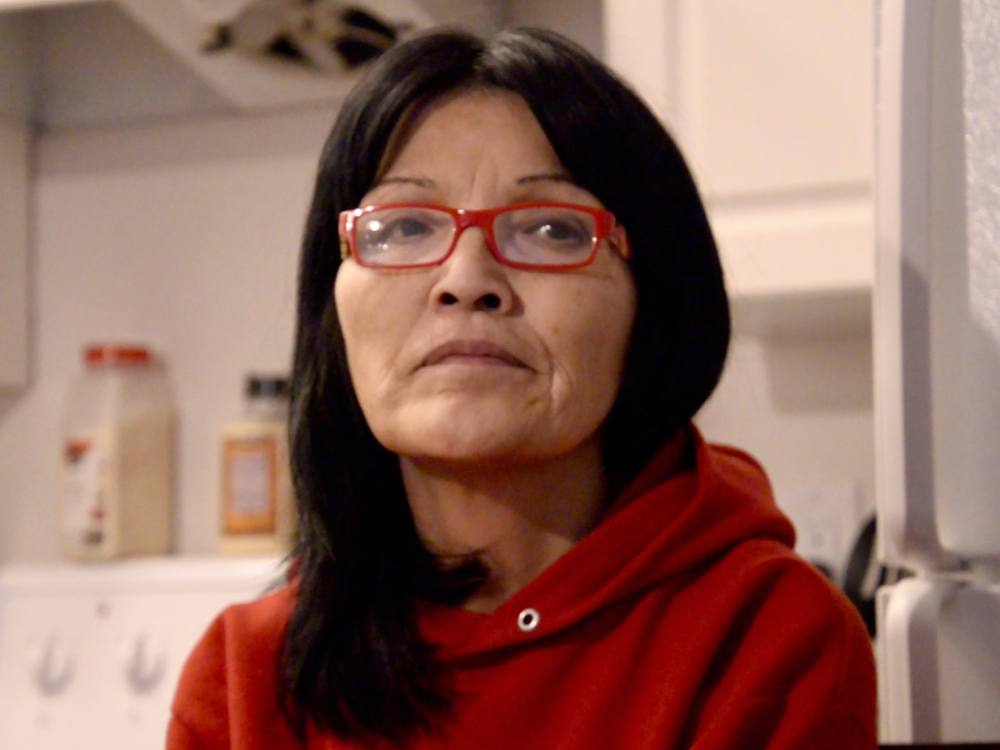

Kathy Poole was eight years old when she was awakened in the middle of a warm summer night in the late 1960s. Her family’s log cabin in Finlay Forks, a town north of Prince George, was about to be submerged by a suddenly forming reservoir that would rise until it became the largest lake in British Columbia, deeper than the Eiffel Tower is tall. The riverbank beside the house began falling away as water pulled at its edges. Her parents, siblings and her grandpa Isaac started to panic. “I could see my dad getting very scared for us,” she said. “We had to get the heck out of Dodge.”

Leaving behind most of their possessions and a kitten, her mom and dad piled their family of 13 — grandfather included — into a boat. Poole remembers watching the bank collapse as they travelled north up the Finlay River. “Me and my brother, we thought the world was ending,” she said. “Some of it seems like a dream.”

But it became a living nightmare for Poole’s family — and for the Kwadacha First Nation to which they belonged. Their home was about to be sacrificed to someone else’s dream of progress. The lake that forever drowned the family house spread wide behind the W.A.C. Bennett Dam, its 186-metre-high wall blocking the Peace River in order to turn turbines, a feat of engineering that still lights a quarter of the province.

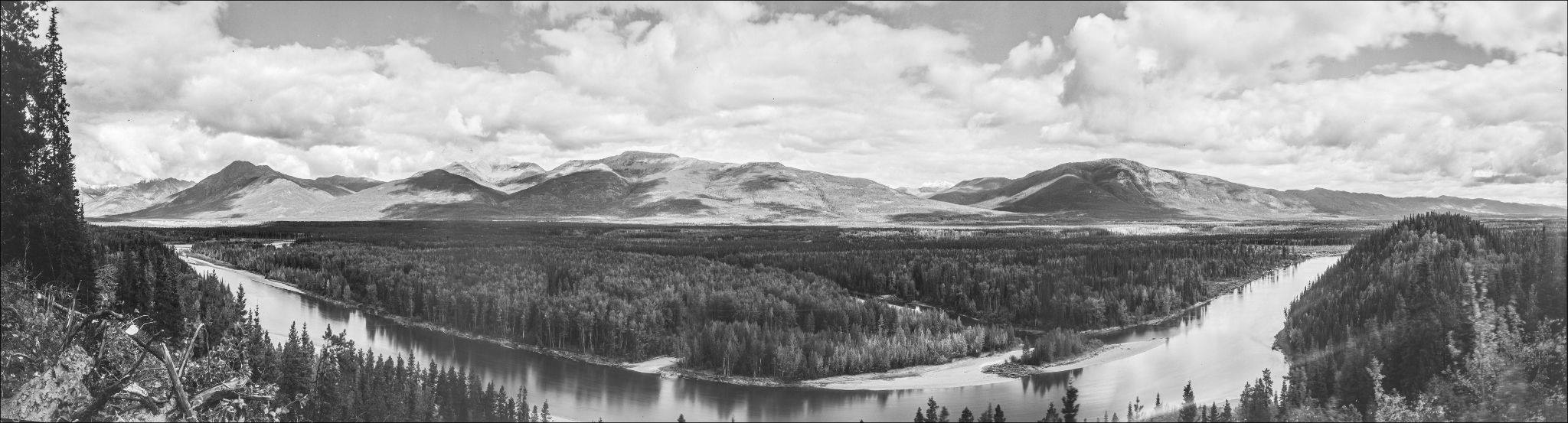

The Kwadacha First Nation is a gravelly ten hour drive north from Prince George on a good day, and it often takes a scratched door or a popped tire to get there. Sometimes referred to as the “Serengeti of the North,” the territory sits at the northern end of the Rocky Mountain Trench — a band of valleys nudged against the mountain range of the same name that extends down through British Columbia into Montana. The trench is a home to rich alluvial soils, teeming biodiversity, and the province’s biggest arteries of freshwater — the Peace and Columbia River valleys.

The trench, for Poole — and for her ancestors over the course of 13,000 years — provided food, community, culture and independence. But those who ran the province gave it their own name — the “power trench,” whose rivers would be channelled, stymied and pumped into a series of hydropower facilities.

The nation had no say in what would happen to their territory, nor did the myriad other First Nations living along the trench who would suffer similar consequences. But on TV, newspapers and in the legislature, B.C.’s hydropower bonanza marked an era of optimism, championed by the charismatic politician for whom the dam that inundated the trench was named.

‘I see thousands of jobs’

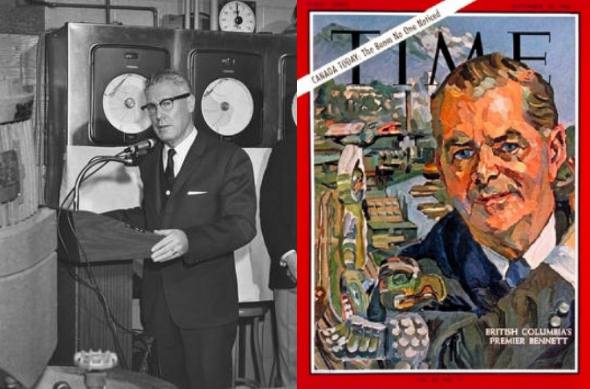

William Andrew Cecil Bennett was born at the turn of the century in a tiny New Brunswick cabin. His father was a frequently absent alcoholic, and so William and his seven siblings — of which five survived infancy — were raised almost entirely by their mother.

As a churchgoing teenager, Bennett vowed to be different. He began to covet inspirational books, like the 1894 classic, Pushing to the Front, that claimed “the world makes way for the determined man.” At 18, he joined his father on a trip out west until the two fought and split up, but Bennett never forgot the Peace River Valley. “I saw a lot of great country that was practically empty of people and needing development,” he later recalled.

In 1952, W.A.C. Bennett became premier of British Columbia, launching the populist conservative Social Credit party into power. Despite the Socreds’ stated free enterprise ideals, Bennett sprung for a surge of new roads, ferries, tunnels and a railway to the province’s north. Then he moved on to hydropower.

Bennett imagined great potential for the northern half of the province — and damming the Peace was a critical first step. “We needed to develop power lines and generating stations everywhere if we wanted to attract industry to British Columbia,” he said.

For a while, he courted the interests of Axel Wenner-Gren, a tycoon of various enterprises including the Electrolux Vacuum. Wenner-Gren’s bid for the north included a futuristic monorail, and, more interesting to Bennett, a hydroelectric dam. But when Wenner-Gren’s ties to the Nazi party surfaced, including a luncheon at the estate of war criminal Hermann Göring, the plan was swiftly sacked.

Bennett now needed a new financier, but B.C.’s private electricity company, BC Electric, refused, claiming that the province had enough power to last the next decade. So Bennett disbanded and nationalized the company in August 1961. The result was BC Hydro, the crown corporation that continues as a monopoly utility in much of the province today.

With the company under the government’s wing, Bennett, who was also the finance minister, could manipulate funds to dam the Peace. Crown corporations like BC Hydro had the added benefit of shouldering colossal amounts of debt that wouldn’t show up in government debt ledgers. The Bennett Dam also helped the premier leverage negotiations with the U.S., which wanted a string of dams built in Canada on the southern Rocky Mountain Trench, to control their flooding. The agreement, the Columbia River Treaty, was signed two years later.

Bennett’s determination to develop the Peace became a personal mythology. In interviews, he often repeated a story — its accuracy unverified — of travelling to the valley in the 1950s. “One day, I went up to have a look at the Peace, which then was a little muddy river,” he said. A trapper approached him, so the story goes, and asked “Mister, what are you looking at?” to which Bennett responded. “I see cities, prosperous cities, beautiful schools and hospitals, universities. I see women doing their baking in ovens that use electricity. I see thousands of jobs all resulting from what you and I are looking at right now.”

“Isn’t it funny,” said Bennett, describing the encounter. “One person can see something, an opportunity, a chance; and another can see only mud.”

In 1961 BC Hydro started building the W.A.C. Bennett Dam.

‘We were one big family’

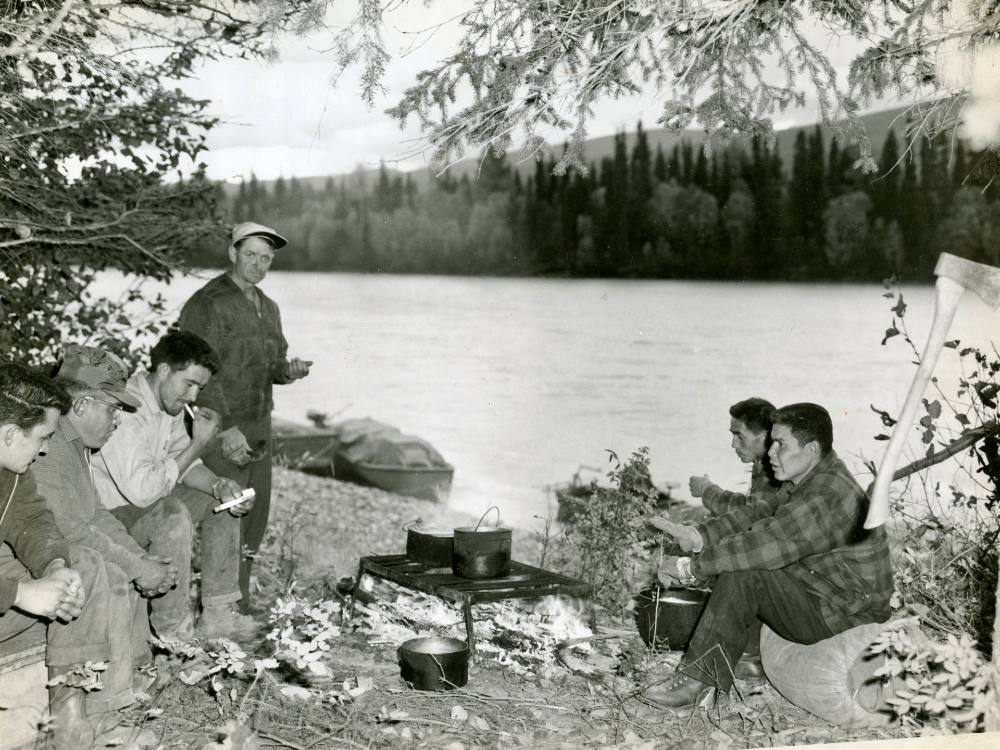

In those early days of the dam’s construction, a few hundred kilometres upstream from the site, the smell of smoke and moose meat drifted through the wall tent Kathy Poole’s father set up — complete with a floor and a stove outside — on the banks of the Finlay River.

Poole remembers carefully placing leaves on sticks, pretending they were pieces of moose meat drying in the sun, as her mom made the real thing just metres away. Sometimes river rocks impersonated huts.

Her parents were experts on the territory. Her dad, an avid hunter, was known for returning with a moose to feed the community using only a single bullet. Her mom was a midwife, and was often out delivering babies. Once August came, Poole’s family would head up the trench’s steep mountains — “very hard on the legs” — to hunt groundhogs, sheep and goats fattened up by summer feasting. Those animals would feed families through the winter.

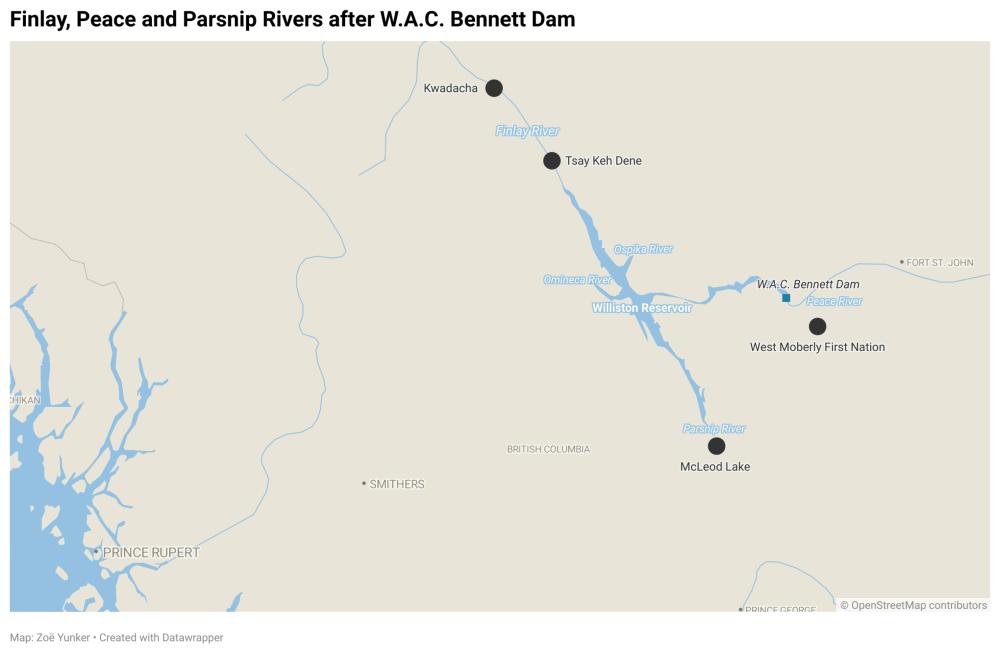

The Kwadacha are one of three Tsek’ene-speaking nations, who collectively refer to themselves as the Tsek’ene Dene. Their presence in the northern Rocky Mountain Trench dates back millennia, to the earliest known inhabitants in the province. The other Tsek’ene Nations — the Tsay Keh Dene and Mcleod Lake First Nation lived to the south on the Finlay — a river that once forked and wound together like a cluster of noodles. But to think of the Tsek’ene Dene (Tsek’ene for people) as three separate nations, before the dam came, would be wrong. “We were one big family,” said Kwadacha Nation member and former councillor Mary-Jean Poole, “’One people' they’d say.”

Tsek’ene Dene never stayed in one place too long; instead they moved on the land with the changing seasons. Towns existed, but often just as touchpoints and meeting places until families returned to the land they tended to, sometimes using controlled burns to manage wildfires and attract animals feasting on the new plant growth that follows. Fluid living helped spread out a community’s footprint, but it required an encyclopedic knowledge of the land, water and animals. “They knew where to go,” said Poole, now an elder herself, of the generations before her.

Before the dam, the nations lived throughout the Finlay River, a striation etched across the trench that met with the fingerlike branches of the Ospika and Omineca rivers before flowing into the Parsnip in the south and the Peace in the east. Those waterways provided a year-round highway for the Tsek’ene Dene, who walked ancient trails, travelled by riverboats, and in the winter, used snowshoes, sleighs and dogsleds to traverse frozen surfaces.

The Tsek’ene Dene’s distance from urban centres meant colonialism was slow to arrive. Particularly for the northernmost nation, the Kwadacha Tsek’ene, whose reserve in Fort Ware was imposed in the 1950s — along with the nation’s former name, then-called Fort Ware Indian Band. Even after that, the region was “more or less beyond state control,” said Daniel Sims, a member of the Tsay Keh Dene Nation and an associate professor at the University of Northern British Columbia. “Reserves existed, but no one was kept on reserve,” he added. That’s partly because much of the territory was roadless, and northern Indian agents were scarce.

The fur trade of the 1800s depleted animal populations and introduced a trading post at Fort Ware, but before the flooding of 1968, the Kwadacha First Nation, like other Tsek’ene communities, maintained their traditional land tenure system, tended to by family groups, extending throughout the region’s boreal forests where lodgepole pine, spruce trees and huckleberry sided thousands of boggy wetlands.

Emil McCook saw it all change.

Born near Dease River, close to the Yukon border, McCook moved to Fort Ware, his mother’s hometown, at three years old. As an adult, for 38 years, he was chief of Kwadacha. Now in his 70s, he still dons his signature cowboy hat, its brim framing friendly eyes and a grey mustache. In the 1990s, McCook would change the colonially named Fort Ware Indian Band (and its reserve) to Kwadacha, the Tsek’ene word for “big fire” — in an ode to the communal fires lit in the village to ward off up to -60 C winds that swept through the trench.

McCook was among the first generations of Kwadacha members who attended residential schools, beginning in the 1940s, where he and his classmates were barred from speaking the Tsek’ene language. When he returned from school, as a teenager, McCook would accompany his uncle, Chief John McCook, to learn the ropes. So he was there when representatives of the Department of Indian Affairs made their first and only trip to Fort Ware. Their message: Move off your territory.

“Fort Ware didn’t want to move anywhere,” McCook said. “This is our home, eh? We’re talking about our traditional homeland — our ancestors and our grandfathers.”

No one from the province properly informed the Kwadacha Tsek’ene about what was about to happen, said McCook. “We had no idea what BC Hydro’s plan, or the government’s plan, was at that time.”

The BC Forest Service released a film about the endeavour, claiming their workers used special machines to cut trees “like a child cutting flowers with scissors.” Reality was far more crude: chains dragged across the forest pushed down everything in their path. Ultimately, though, lots of forest remained in place when the water rose over it, and that created dangers that exist still today.

Ron McCook, Emil’s brother, remembers how fast it happened. He was 15, and had a job stacking wood on the icy river in preparation for the flood. “We got out there and the lake was rising,” he said, remembering the sight of water coming towards them over the ice. They didn’t have enough time to move their Jeep or a giant tree crusher, both of which are now sitting somewhere at the bottom of the reservoir that would bear the name Williston Lake.

'It gets rough’

Shirley Van Somer remembers the bright red trim on Art Van Somer’s boat, and the mirror-smooth water as her father-in-law left shore that day in the summer of 1968. In less than a year, the river had turned into 1,761 square kilometre Williston Lake, its seemingly endless horizon punctuated by masses of jagged floating logs. The late Elder Laura Seymour was standing beside her on the bank, ready to head back to camp. “No, just wait. I want to watch for a minute,” said Shirley. The boat, now just a red dot in the distance, had gone still.

“When that wind comes up out of the Peace it gets rough,” Shirley recounted. It would howl through the mountains and across Williston Lake, whipping up whitecaps twice as tall as a moose. Kwadacha’s riverboats, built with flat bottoms to skim on gravel and meander down channels, were now dangerously out of place.

Then there were the logs — a four-kilometre-long mass of stray timber floating about the lake that locals called “the plug.” You couldn’t predict where the plug would show up. Sometimes “it was nothing but logs on the lake” said Shirley Van Somer, other times, not a log in sight. Sometimes dead trunks would catapult out of the water at random as trees left standing finally relinquished their grip on the lakebed.

As Shirley Van Somer paused to fix her eyes on her father-in-law’s motionless vessel, gunshots rang out across the lake. She knew that Art’s boat was sinking. Onboard, some passengers, including Art’s seven-year-old son Ralph, couldn’t swim. Art put Ralph on a log and began to throw the boat’s cargo, including 45-gallon drums of fuel, overboard in an attempt to keep afloat. Shirley’s husband Bob was the first to make it to his father’s boat to rescue him.

“Art was never the same after that accident,” said Shirley. After a long career shuttling people and supplies the length of the Finlay River, he never worked on the water again.

Eventually, the province sold Van Somer a tugboat, which his son, Bob, Shirley’s late husband, ran for him. “Bob was on there 24-7,” she said. But even aboard a more capable vessel, the reservoir could be a deathtrap.

One late fall evening Bob Van Somer’s deckhand, William Poole, fell overboard. “Bob was pulling into shore with the barge and he had the spotlight to see where he was going and he turned around and William was gone,” said Shirley Van Somer.

Bob immediately called the RCMP detachment based in MacKenzie. “They didn't even bother coming up and looking or nothing. It was just another Indian,” said Shirley.

She added, “There’s lots of bodies in that lake.”

The Mackenzie RCMP kept a list of persons gone missing on and around the reservoir, none of whom were found. “Williston Lake is not renowned for giving up bodies,” said Sgt. Jack Keddy in a 1985 article in the Prince George Citizen. “It seems to keep them.” That’s partly because the nine rivers that once fed into the Finlay River are now flowing inside the reservoir, forming currents capable of dragging anything along with them.

‘We were cut off’

Williston Lake, named for Ray Williston, W.A.C. Bennett’s minister of land, forests and water resources, is the seventh-largest reservoir in the world. Its creation quickly stranded the Kwadacha Tsek’ene in their own territory. Their reserve at Fort Ware was farther north than the water lapped, but the reservoir created a roadblock, cutting them off from much of their territory. Travel in the choppy, debris-strewn lake was risky, and trail networks, many of them thousands of years old, were now underwater. For over a decade, many people in the nation had no way out or in.

“We were cut off from transportation,” said Emil McCook. “Unless you could afford to charter an airplane. Not many could afford to do that.”

Food became scarce. Moose, always a main staple, now were fast diminishing. In anticipation of the floods, B.C. attempted to liquidate moose herds, allowing hunters to kill as many animals as they could if they brought their jawbones to the Forest Ministry.

When the water did rise, thousands of animals died attempting to cross the reservoir, getting stuck between miles of debris. Others climbed to high ground only to be trapped as the water advanced.

In his travels with the tugboat, Bill Van Somer — Bob’s brother — reported finding hundreds of moose, elk and beaver floating in the lake. The smell of rotting animals filled the trench.

“It's very devastating for us because we live on those animals,” said Mary-Jean Poole. “Nowadays you don't see that much animals around. Not like long ago.”

Fish became poisonous. When forests and agricultural lands flood, methylmercury-producing bacteria eat the soil and vegetation — and then pollute the fish. After the floods, more than a small mouthful a week of local species like bull trout and arctic grayling could be toxic to an adult.

“We had to haul our supplies in by aircraft,” said Emil McCook. Exorbitant prices for food were compounded by the fact that communities were now cut off from worksites in places like Mackenzie and Prince George. Logging, mining and tourism industries gained stronger footholds on the territory, but for the Kwadacha Tsek’ene, money, more important than ever before, was as inaccessible as the land.

“I travelled lots when I was young,” said Kwadacha member, Laura Seymour, in the documentary film Kwadacha by the River, which vividly details the reservoir’s impacts. “I wish those were the days again.”

Immediate changes soon gave way to deeper, more lasting ones. Before the dam, families living along trap lines would come together for gatherings in the spring and wintertime at the end of harvests. Elders said those gatherings were “like Christmas” recalled Verna Charlie, a Kwadacha Nation member, who was a child when the lake transformed Tsek’ene culture. “People got disbanded and pretty much went their separate ways.”

As the years wore on, the three Tsek’ene Nations became estranged from one another, left to face the dam’s impacts alone. The McLeod Lake First Nation, the closest to industrial development, was required to stay on reserve, and Tsay Keh Dene were forced to relocate to new reserves outside of their traditional territory as their members in Finlay Forks, Fort Grahame and Ingenika were flooded. And although they were the farthest from industry, the Kwadacha Nation, too, became tied to the reserve as transportation and food systems diminished.

The reservoir, in the meantime, kept claiming lives. Nine people have drowned in its waters over the years by some estimates. One October night in 1992, Kathy Poole and her husband Brian were traversing its waters in a barge on their way to Fort Ware. They had plans to move to Prince George. Brian, a mechanic, would open a shop. But in the blackness of that night, Brian walked out of the barge’s small cabin to check around. Poole never saw him again.

For weeks afterwards, Poole didn’t sleep or eat. When she went to seek medical attention, she found out she was pregnant. She named her daughter, Brianna, who is now 28, after the father she would never meet.

‘The boom that no one noticed’

When the Bennett Dam was constructed, the technology to transmit the power to Vancouver was still nascent. And yet when Bennett flipped the dam’s switch on Sept. 28, 1968, he declared that grand project would “help everybody in this great country of ours.”

The current head of BC Hydro marvels at the bet Bennett made. “To do that today would be incomprehensible. Your risk-management practices wouldn't allow you to do such a thing,” said CEO Chris O’Riley in an interview for BC Hydro’s website.

At the time, B.C. had a population of just 1.8 million compared to 5.1 million today, and by some estimates, already had enough electricity sources to power the province for another decade. Not nearly enough for Bennett, though. “The original plan for hydro was to use publicly owned hydro power to attract heavy industry to B.C.,” said Eoin Finn, a former KPMG energy expert. Beyond powering homes, Bennett would sell power at cheap rates to industrial customers — an approach that continues today.

It worked. In 1966 Time magazine commissioned a painting of Bennett for its cover, calling the economic rise of Western Canada, “the boom that no one noticed.” Northern industries began to skyrocket, including hundreds of new mines and a slew of new pulp mills in Prince George ready to capitalize on the glut of cheap power.

But booms can break things, and the Bennett Dam’s wreckage is no exception, leaving British Columbians to weigh what’s owed to those who suffered for its progress. And after a century of jamming rivers around the world, the environmental cost-benefit balance for mega-dams remains a fierce debate (see sidebar).

The spate of mega hydro dams built around the world beginning in the 1930s channelled the spirit of what anthropologist James Scott calls “high modernism,” a method of governing that sees nature as a resource to be exploited. Water was wasted until put to proper use, and dam building seemed like common sense. Who, after all, doesn’t want more money and power? Dams quickly grew to represent symbols of a strong state and independence. India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, for example, used hydro dams — dubbed the “temples of modern India,” — as a path away from British rule.

Dam builders are “like missionaries,” said Rutgerd Boelens, professor of water governance and social justice at Wageningen University. “They want to improve the world. But according to their vision, and because they’re missionaries, they do not see what’s there already.” UNBC professor Sims characterizes the mindset this way: “Like a bulldozer, the new dams will come in order to shape society as it should be.”

In a 1975 interview, Ray Williston was asked whether the decision to build the Bennett dam and its reservoir had negative consequences. No, he said, “it was an absolute wilderness and there were no people, no nothing. Outside of Fort Ware where there were a few Indians and so on. There was nothing in the whole area.”

But authorities were very much aware of the Tsek’ene-speakers and viewed them as obstacles to further plans. “Once the dam was created, there was this push from the federal government to keep Tsek’ene people on reserve,” said Sims. As northern industry ramped up, governments suddenly needed to determine which was “Indigenous land” and which could be freely developed. “Suddenly, you go from being this community that has kind of escaped the attention of the colonial state to this community that is under a lot of surveillance, a lot of control.”

“It was that double whammy,” said Sims, describing the toxic pairing of flooding and residential schools. “Your kids have been taken and your traditional territory is now completely destroyed.”

‘We guessed what was happening’

One day in April 2010 Chief Roland Wilson of West Moberly First Nation was sitting in a monthly Chief’s meeting at the Treaty 8 Tribal Association office in Fort St. John when a technician bounded in from the second floor.

Then-premier Gordon Campbell was inviting them to a press conference at the W.A.C. Bennett Dam the next day. “They wouldn’t tell us what it was,” he said, “but we guessed what was happening.”

The next day Wilson and other Treaty 8 Chiefs stayed away as Campbell disembarked from his chartered plane, filled with officials and a group of retired BC Hydro workers dubbed the “Power Pioneers” who had helped build the Bennett Dam half a century ago.

They joined an invited group of attendees that piled out of buses and moved into the W.A.C. Bennett Dam Visitor Centre where they sat facing floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking the dam’s vast concrete moonscape.

BC Hydro, this long after W.A.C. Bennett’s reign, had 82 dams operating in 40 locations across the province. "As we travel around the world on behalf of British Columbia and tell the world that 90 per cent of our power is clean power, they are in awe," Campbell said to his audience about B.C.’s dams. "They're incredulous that we were able to think that far ahead."

Now Campbell said he intended to put a third dam on the Peace — the Site C dam, which would flood the river’s remaining intact 80 kilometres southeast of the Williston Reservoir — territory belonging to the West Moberly, Prophet River and Saulteau First Nations. Site C would sit just seven kilometres upstream from Fort St. John.

Back in the 1950s, Bennett saw Site C’s potential to turn more turbines. Successive governments tried and failed to start such a project, often because the province’s independent utility regulator, the BC Utilities Commission, said it was unnecessary. But Campbell was about to put Site C back on the plate.

Campbell wouldn’t last, but Site C would. After Campbell resigned in November 2010, Christy Clark took his place as BC Liberal premier and pushed the project forward. She took the extra step of removing the regulator from its role assessing the project. Again, hydro was yoked to B.C.’s progress, this time because Clark dreamed that the province could be a powerhouse for liquefied natural gas, or LNG.

Eastern B.C. was rich in shale gas that, if forced loose by hydraulic fracking, could be piped to the coast, compressed to liquid form, and lucratively shipped to overseas markets, or so believed Clark and the industry experts who had her ear. But the pumping, piping and super-chilling of LNG requires a lot of energy. That’s where Site C fit in. The dam would produce the power, and allow B.C. to claim its fossil fuel export was “greener” than rivals’.

But when it came to Indigenous consent, what had changed?

The Bennett dam, assured BC Hydro’s O’Riley in a 2017 interview, “was built in a completely different context… at a time when people didn't understand Aboriginal rights.” This time, he said, BC Hydro engaged and consulted with First Nations affected and signed financial agreements with six Treaty 8 Nations. And this time they would clear the reservoir’s trees first.

But the West Moberly Nation didn’t sign an agreement with BC Hydro, which went ahead anyway. Wilson’s assessment: “It's the same pile of shit, in just a different way.”

He explained that BC Hydro took the Site C plans off the shelf “and they said, ‘we're moving forward with this.’ Then they came and talked to us. By definition, that's not a consultation process — that's a mitigation process.”

When the dam was announced, the West Moberly were involved in a land planning process for their territory, setting thresholds for types of development they would allow. Site C would have vastly overshot their targets, rendering the plan moot. It became moot in any event. The province shut down the planning process with the nation, and proceeded with Site C.

The West Moberly First Nation know what a hydropower mega-project can do. Their territories are to the east of Williston Lake’s southern shores, and lie southeast of an arm of the reservoir that veers at a near right angle for about 30 kilometres to Hudson’s Hope. “The Williston reservoir completely encompasses us,” Wilson said. “It’s an actual barrier around us.” Like the Kwadacha, Wilson’s Nation moved across the land with the changing seasons. The Bennett Dam and other industrial development made that life impossible.

Now Site C stands to make those impacts even worse, said Wilson.

With local caribou herds facing extinction, West Moberly runs a recovery project that raises baby caribou in pens to give them a fighting chance. Site C, Wilson said, will destroy critical caribou habitat, making the hard job of rehabilitation near impossible.

After a string of losses in the courts, West Moberly launched a major legal challenge arguing that Site C and the two existing dams on the Peace — the Bennett and the Peace Canyon — violated their treaty rights. Last month, the case was adjourned, and the nation is now in discussions with BC Hydro and the province to settle the issue out of court.

‘Mistakes of the past’

Over half a century since the Bennett Dam flooded Kathy Poole’s childhood home, the reservoir’s banks are still receding as water slowly chips away at the sand and soil of the trench. Locals know to be cautious at the water’s edge.

BC Hydro finally apologized for the Bennett Dam’s impacts on the Kwadacha Tsek’ene and other surrounding nations during the opening of an exhibit at the dam’s visitor centre in 2016. CEO O’Riley stated that the utility would not repeat the “mistakes of the past.”

“We recognize a need to acknowledge those parts of the picture that we can’t be proud of,” he said as quoted in the Narwhal.

Eight years prior, and after almost a decade in negotiations, the Kwadacha won a $15 million settlement from BC Hydro for damages from the Bennett Dam, along with annual top ups of $1.6 million that has been disbursed to elders, and to other community programs.

Now the Kwadacha Tsek’ene are working hard to protect what’s left of their territory.

Throughout the 1980s and ‘90s, logging firms clear cut forests to within less than a kilometre from Fort Ware, said Darryl McCook, Kwadacha Nation’s current Chief.

Then the elders drew a line in the sand. “They advised a lot of us that they do not want to see logging past our community,” said McCook. “We've fought for years to protect what we have north of us.”

Under Emil McCook’s leadership, the nation helped forge the Kaska Dena Council in the 1980s — a council of five First Nations, three in northern B.C. and two in the Yukon — with whom they have close familial ties. Today, the council is working with the Dena Kayeh Institute to protect a huge swath of boreal forest in their territories, called the Kaska Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area, a 40,000-square-kilometre conservancy reaching from Kwadacha to the border town of Lower Post — the largest undeveloped forest area in British Columbia.

“It’s been years in the making,” said Darryl McCook. The nation is currently in discussions with neighboring Treaty 8 Nations and the province. McCook is hopeful. “I'm really excited,” he said. “We finally have something under our belt, not just for now, but for future generations.”

But a lasting, painful irony remains. Fifty-four years after the W.A.C. Bennett Dam flooded the valley that supported the Kwadacha Tsek’ene for centuries, the nation cannot use any of the power the mega-project produces.

BC Hydro refuses to build transmission lines to Kwadacha, so the reserve’s electricity comes largely from diesel-fired generators. And because those living in Kwadacha are considered remote customers, they pay more for their power per hour. BC Hydro provides some funding to help with power bills, but it’s often not enough. “There are a lot of people that owe a lot,” said Mary-Jean Poole.

Which raises the questions explored in tomorrow’s closing piece in this series. If B.C.’s electricity system wasn’t something that happened to First Nations, but instead was one they shaped, planned and profited from, what would that look like?

‘You have to live with it’

Kathy Poole, now an elder, still vividly remembers that long ago night when she was awakened by her parents to escape the floodwater that would change everything in the name of a certain vision of progress.

Each August she leaves her home in Prince George to visit Kwadacha, where she cooks for the other elders as they camp, prepare moose, pick berries and spend time in each other’s company. The Kwadacha Tsek’ene have begun gathering again around harvest times, as they did before the water rose. “It’s just like in the old days,” Poole said.

To make her visits, she drives off the smooth pavement and onto the single, gravelly road beside the reservoir that erased her home and claimed her husband’s life. She’s gotten used to it.

“What can we do about it?” she asked as she helped her grandkids cook rice and vegetables for lunch. “You have to live with it.”

After a pause, she added. “They should pave the damn road.”

Read the wrap-up of this two-part special report: "The Coming Indigenous Power Play": Inside the First Nations-led plan to decolonize British Columbia’s electricity. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Energy, Rights + Justice, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: