[Editor’s note: Following this report a halt was put to tanker traffic in Active Pass. Read the followup piece.]

On a calm Friday afternoon in late April, avid naturalist Barry Swanson was watching Active Pass from his home on Galiano Island, keeping an eye out for the killer whales that swim by on a regular basis.*

Instead of orcas, he was shocked to see an oil tanker traversing the narrow channel.

The MV Kassos was sitting low in the water, its hull heavy with petroleum products bound for Los Angeles.

Swanson is the co-founder of the non-profit Salish Sea Orca Squad, a group that works to raise awareness about the region’s killer whales. In an interview with The Tyee, he says he was very concerned to see dangerous cargo being shipped through the narrow waterway.

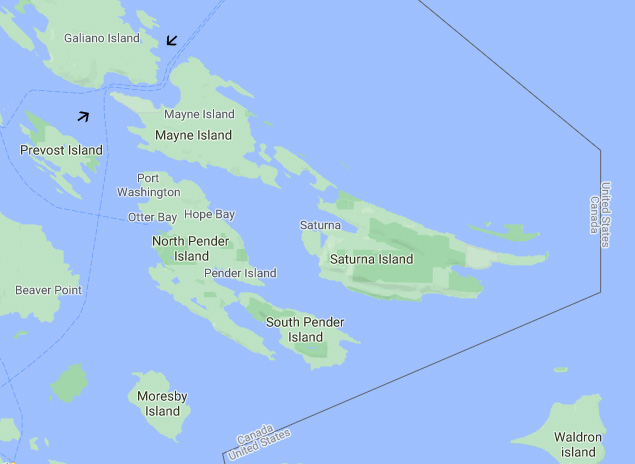

Active Pass sits between Mayne and Galiano Island. The channel is deep but narrow — 302 metres wide at its skinniest — and features strong currents, rip tides and a blind corner, according to Fisheries and Oceans Canada. It’s also a route favoured by BC Ferries, connecting Tsawwassen to Swartz Bay and the mainland to the Southern Gulf Islands.

It’s extremely unusual for an oil tanker to take Active Pass instead of the neighbouring Boundary Pass, favoured by almost all other commercial routes for its wider, calmer waters. Swanson says he’s never seen an oil tanker take the pass before.

“When you have a tanker travelling through these waters... there is always tremendous danger with dangerous goods being spilt in any amount. It would be a disaster for that to happen,” Swanson says.

Swanson and his partner, Rachelle Hayden, reached out to marine oil spill expert Gerald Graham with a picture of the ship and the question. “Is this route even legal?”

The short answer to that question is yes. But that raises questions about maritime safety and the future of commercial shipping in B.C. waters.

Both Swanson and Graham, who has worked in oil spill prevention for 30 years, assumed the route would be off limits following a deadly crash in Active Pass between a B.C. ferry and a freighter 50 years ago.

On Aug. 2, 1970, around 11 a.m., three passengers were killed when the 159-metre-long freighter MV Yesenin crashed into the side of the Queen of Victoria. The day was bright and clear and the tides were nearly slack, meaning currents through Active Pass were minimal, according to reporting by the Delta Optimist.

NB It's called "Active" for a reason! https://t.co/33tJBMwDf3

— Gerald Graham (@SalishSeaFuture) May 4, 2021

After the crash, ship pilots avoided using Active Pass, but no rules were created to ban them from taking that route, says Pacific Pilotage Authority CEO Kevin Obermeyer.

The authority is a federal Crown corporation that oversees shipping in B.C. waters. Under the Pilotage Act, it contracts pilots from the private company BC Coast Pilots to guide all ships over 350 tonnes through coastal waters. This ensures all ships are piloted by licensed professionals familiar with the area and the region’s conditions, Obermeyer says.

As a safety measure, all pilots’ shifts are capped at eight hours to ensure they’re not overly tired when clambering on to the big ships and guiding them through the coastal waters. When a trip is expected to take over eight hours, two pilots will be on board to trade off when one hits their eight-hour mark.

Once a BC Coast Pilot is at the helm, they can more or less take the ship wherever they want. Pilots must follow the loose guidelines under collision regulations of the Canada Shipping Act and most large ships stick to a traffic separation scheme in waters heavily used by commercial boats, Obermeyer says. Ships also have to check in with the coast guard’s Marine Communications and Traffic Services, which keeps tabs on ship locations.

Under the Canada Shipping Act, the Pilotage Act and the Canada Marine Act, which Transport Canada says together regulate marine safety, the MV Kassos was following the rules when it took an oil shipment through Active Pass.

The MV Kassos is 102 metres long, which means it’s considered a small tanker, Obermeyer says. There are rules for tankers over 40,000 tonnes transiting Boundary Pass, but nothing specifically for tankers this size, he says.

But a small tanker, similar in size to a medium-sized ship in the BC Ferries' fleet, can still pack a hull full of oil. Graham calculates it can carry up to 41,513 barrels of oil — if one of the ship’s 12 cargo tanks ruptured, 3,459 barrels of oil could spill out.

Graham was also upset to see the tanker going through the pass while being closely followed by BC Ferries' Salish Raven. Swanson says a Seaspan transport preceded the tanker.

“The danger is, whether or not there are ferries there, it’s a riskier route than Boundary Pass,” Graham says. “It’s not rocket science; you don’t need a PhD in nautical engineering to see the risk is a relevant thing. If you can avoid it, or get the risk as close as possible to zero, why not do it? In this case you’re taking a risk, an unnecessary risk, however slight, by sending a tanker through there or any commercial vessel through there.”

FYI, here's @lostfrequency__'s April 23 shot of the laden tanker MV Kassos in Active Pass, & my @MarineTraffic screengrab of the @BCFerries vessel MV Salish Sea in close proximity. NB Active Pass is not the recommended route for medium draft and large vessels, let alone tankers. pic.twitter.com/zDKlxVLjTv

— Gerald Graham (@SalishSeaFuture) April 30, 2021

So why did the pilot take the riskier route?

According to Obermeyer, it was to save time and money.

This was the MV Kassos’s second time navigating Active Pass. The first time it was empty and heading to the Imperial Oil Ioco Terminal dock in Port Moody. The second time it was filled with petroleum products and bound for Los Angeles, Graham says.

For both trips the route was calculated to take less than eight hours so that only one BC Coast Pilot was on board, Obermeyer says. But the pilot miscalculated the tides (tidal forecasts can have all the right information but still miss the mark, similar to weather forecasts, he says), and the MV Kassos was slower than predicted.

The pilot decided to take Active Pass instead of Boundary Pass to shave two hours off the journey and avoid going over their eight-hour shift, which would be a safety regulation violation, Obermeyer says.

To have a second pilot on board costs more money, and when a pilot goes over their eight-hour shift the shipping company has to pay a penalty that increases pilotage fees, he adds.

In an email between Graham and Obermeyer, which Graham later published, Obermeyer said the pilot has an “exemplary track record” with over 10 years of experience taking “much larger vessels through Active Pass.”

The pilot has not worked as a BC Ferries captain, Obermeyer told The Tyee.

In the same email, Obermeyer says the Pacific Pilotage Authority will issue an internal notice to pilots “that will stop liquid bulk carriers under pilotage of any size transiting through Active Pass unless it is for some unforeseen emergency.”

That notice will go out this week, Obermeyer told The Tyee.

BC Coast Pilots also issued a statement April 30 saying it will review the route.

The MV Kassos will be the last tanker spotted in Active Pass, Obermeyer says.

But that might not be true, warns Karen Wristen, executive director of the Canadian environmental organization Living Oceans Society.

Only Transport Canada has the authority to restrict traffic to designated shipping lanes, Wristen wrote in an email to The Tyee.

“It’s nice of the Pilotage Authority to recommend to their pilots that they avoid Active Pass; but they can’t make them avoid it, and if the ship’s master and the pilot both want to save time and money, they will take the pass,” she says.

A notice to pilots means a pilot could be punished by the Pacific Pilotage Authority if they took Active Pass, but the notice isn’t backed by law so there is nothing to deter a ship’s master from pressuring a pilot to take the shorter route, Wristen says.

“The effect of the notice, hopefully, will discourage such conduct; but it won’t prevent it,” she says.

Restricted traffic is exactly what Swanson and Graham want to see. It’s “selfish and completely unacceptable” that a pilot would take an oil tanker through Active Pass to save time and money, Swanson says. The Salish Sea is an extremely healthy environment, but an oil spill or similar environmental disaster would devastate local marine life, including southern resident killer whales, Swanson says.

For Graham, issuing a notice to pilots is a “fantastic step in the right direction,” because it would help a pilot put their foot down if a captain was pressuring them to take the Active Pass shortcut.

But as an internal document, the public won’t be able to read it and won’t know when there is an infraction, he says.

A notice to industry would take the protection a step further by creating a public document holding the ship’s captain and owner accountable, but the notice to pilots might be enough to protect the pass, Graham says.

Graham also points to Obermeyer’s email that says the notice to pilots will cover “liquid bulk carriers under pilotage of any size transiting through Active Pass,” which would apply to small tankers, like the MV Kassos, and ships up to six times its size.

One way Transport Canada could restrict commercial traffic through Active Pass is to introduce size restrictions on the vessels allowed to use the waterway, Wristen says.

At this time, Transport Canada is not considering introducing size restrictions or any additional safety measures for Active Pass, spokesperson Cybelle Morin said in an email.

Under the current regulations there have been no collisions between commercial vessels in Active Pass in the past 50 years, Morin says.

“Transport Canada, along with our partners in the Canadian Coast Guard, continue to monitor high traffic areas on the B.C. coast, including Active Pass, and will address issues if and where necessary,” Morin wrote.

That stance is shocking, Wristen says.

B.C.’s waters are set to see an increase in tanker traffic as projects like the Trans Mountain pipeline come online. That might not mean an increase in tanker traffic in Active Pass, as Trans Mountain hearings have suggested tankers would follow set shipping routes, Wristen says, but taking the pass can still save shipping companies time and money, so why would they avoid it?

“There’s a huge problem inherent in taking a reactive stance to safety where accidents involving laden oil tankers in the Gulf Islands is concerned,” Wristen wrote in an email.

“A single oil spill in Active Pass would be carried so far, so fast on the high currents there that ‘cleanup’ would be impossible. It would foul beaches throughout the Salish Sea, impact the southern resident killer whales and their critical habitat and countless other marine species. It would impact fisheries and tourism for decades to come.”

* Story updated on May 11 at 8:40 a.m. to reflect how the mammal-eating transient orcas are spotted every couple of days in Active Pass, not the fish-eating southern resident killer whales. The southern resident killer whales swim through Active Pass a dozen times per year, according to the Salish Sea Orca Squad. ![]()

Read more: Transportation, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: