The first time I met David Schindler 30 years ago, he occupied an office the size of a closet on the eighth floor of the zoology building at the University of Alberta.

Piles of scientific papers erupted about the room like academic volcanoes. So much paper obliterated a desk that Schindler perched his computer on a TV tray. He didn’t like cities, and drove to work every day from Wildwood, Alta., 100 kilometres west of Edmonton. There he and his wife Suzanne Bayley were correctly known as “dog people.” They owned 85 sled dogs.

But that’s not what dumbfounded me. Schindler just didn’t look or behave like a university professor. People commonly mistook the lake ecologist for a rig worker or a farmer. The short muscular man could lift a car, ride a 10-dog sled team over 5,000 kilometres of terrain every winter, wrestle a group of men down a stairway (yes, he did that at Oxford University), hunt a moose and happily down a bottle of whiskey with no noticeable effects.

And then there was the peerless, cutting-edge science. By the age of 50, Schindler was one of the world’s top freshwater ecologists. Politicians and bureaucrats feared him because he wielded scientific evidence the way a Samurai swung a sword. His groundbreaking research on phosphates, acid rain, climate change, UV radiation and transboundary pollutants had rattled governments in North America and Europe and driven important policy changes around the world.

Schindler’s work, and that of his many collaborators, had also changed the daily life of Canadians. Whenever anyone added a phosphate-free detergent to a washing machine, they were honouring the work of Schindler’s team at the Experimental Lakes Area, one of Canada’s greatest science experiments.

Last week Schindler died at the age of 80 after a long struggle with an inflamed heart. I lost a patient mentor and friend. Canada lost something far greater: a giant of freshwater research, a guardian of the boreal, a defender of treaty rights, a speaker of uncomfortable truths. A visionary scientist.

“He was the greatest and most influential water ecologist on the planet,” noted long-time colleague John Smol, the Canada Research Chair in environmental change at Queen’s University.

But Dave was much more than that. In a mining republic often cavalier about water, he constantly offered a different ethic. He cared about the sanctity and beauty of lakes and their creatures with a fierce passion. And he worked tirelessly for the welfare of future generations. His energetic life flowed defiantly like some untamed northern river. And whenever the banks overflowed, well, that was only natural. He was a force of nature for nature.

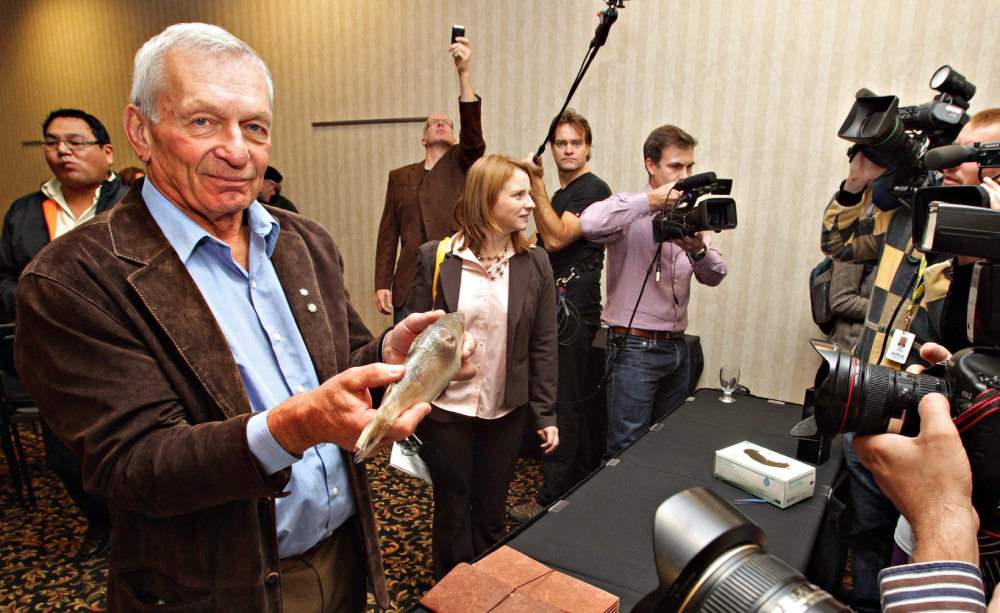

To his many colleagues, Schindler set a new bar for the communication of science. It wasn’t enough to publish a paper. If your research had policy implications that affected fish and ordinary water drinkers, Schindler believed scientists couldn’t be wallflowers. They had a moral duty to present the data to politicians whether they wanted to hear it or not.

A rare combination of gifts placed Schindler at the pinnacle of his field. First and foremost, he knew the literature on water science — knowledge grounded by years of paddling on lakes and rivers like a voyageur. (Dave often sat down in his barn to read a stack of scientific papers while doing constant one-arm curls with a 40-pound dumbbell.) He also had the capacity to lead a team and the work ethic to get the job done. Next, he got excited. Then he didn’t leave the evidence on a shelf. “He was determined to show that science had value in everyday lives and that you dismiss it at your peril,” recalled Smol.

He was not only a force of nature for nature, but for those by his side, as well.

In 1974, a wildfire threatened the Experimental Lakes Area near Kenora, Ont. While fighting the blaze a helicopter had dropped a water bucket in a lake. Schindler, of course, volunteered to dive to the bottom and retrieve it. As the float plane ferrying Schindler to his task emerged from clouds of smoke, the pilot prepared to touch down on the lake with firefighting helicopters swirling about. Schindler just had time to cover his head before the plane hit a boulder jutting out of the water.

With his face bloodied and one arm broken, Schindler kicked open the door and jumped into the water. The pilot, dazed and battered, confided he could not swim. (Dave always chuckled at this point in the story.) After coaxing the man into the water, Schindler cradled the pilot with his good arm and swam to the rock ledge. Here he waited for help by lodging his broken arm in a rock crevice while hanging onto the pilot. The next day he showed up at work with a cast on his arm and an imprint of the instrument panel on his face. He explained that he couldn’t stand the stench of the pulp mill in Dryden, Ont. coming through the window of his hospital recovery room. "And I hate hospitals.” And that’s vintage Schindler.

BEGINNINGS

David Schindler was born in Fargo, N.D. in 1940 because there wasn’t a hospital in his hometown of Barnesville, Minn. He grew up the first of four siblings in a German immigrant family in the northern lake country where remnants of tall grass prairie still butted up against the forest. His father and uncles ran a potato wholesale business, a 1,200-acre farm and a beer depot. His mother Angeline, a college grad, taught music.

But it was the geography of water that shaped Schindler’s life. Once he had finished his farm chores, he headed to lakes named Pelican and Cormorant. There he fished for pickerel and sunfish bigger than his hand. He owned his first .22 at the age of six (to shoot starlings) and bought his first outboard motor, a Hiawatha, at 12.

When not mucking about outdoors, Schindler often got lost in the novels of James Oliver Curwood. During the 1920s the bestselling author wrote adventure tales that mostly took place in Canada’s boreal forest. (The Canadian government even hired Curwood to travel around the north.) His popular sellers included The Wolf Hunter, The Flaming Forest and Kazan, Wolf Dog of the North. They left Schindler with one desire: “Boy, I wanted to see that country.”

At school, teachers directed him toward engineering and medicine but neither caught his fancy. The wrestler and football player (he declined an invitation from the NFL) wanted to work outdoors. By chance a science teacher at the North Dakota State University suggested biology and sent him off to measure the energy contents of lake organisms with a bomb calorimeter over the summer. And that’s when the water bug seized him.

One thing led to another, and Schindler soon found himself studying on a Rhodes scholarship with Charles Elton, one of the founders of ecology in Oxford, England. Elton had written The Ecology of Invasions by Animals and Plants, a classic describing how global biological exchanges were eroding lakes and landscapes with invasive species. The book put Schindler’s hair on end and made him an ecologist for life.

At Oxford, Schindler displayed an aversion to being intimidated. The very day the Midwestern farm boy arrived, a group of mostly British students barged into his room and asked him to sign a petition protesting the Bay of Pigs invasion of Fidel Castro’s Cuba. Schindler politely declined: he knew nothing about the issue. When the group said they would not leave until Schindler signed, a pushing match ensued. “I shoved one guy and a whole bunch tumbled down the stairs. I was hauled into the master’s office and given a lecture on civil behaviour.” Over his career Schindler posted a lot of bureaucratic reprimands on his office door.

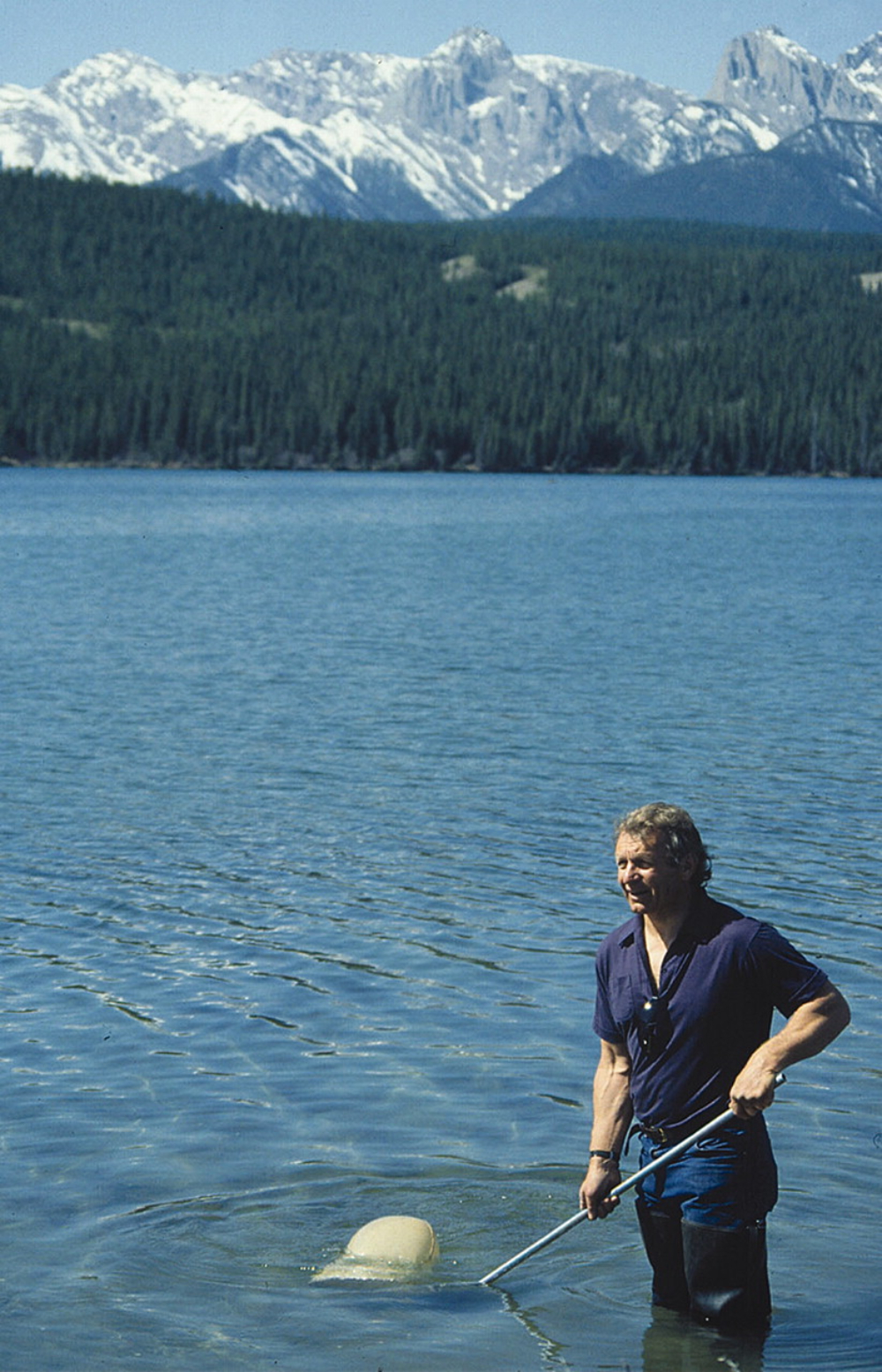

In 1967, the able young scientist was recruited by Jack Vallentyne at the Fisheries Research Board of Canada to work in the lake country of northwestern Ontario. Vallentyne had hired a bunch of topnotch ecologists from Japan, the United States and Switzerland and promised them great things. The idea was to take water ecology out of lab bottles into the real world: whole lake experiments. If it could be done, it would revolutionize limnology, the study of inland waters.

Aware of Schindler’s physical prowess and can-do attitude, Vallentyne offered the Young Turk the directorship of the entire program the day before he departed to Kenora. “I’ll think about it and let you know once I get there,” replied Schindler. “Then he just railroaded the operation from there on in,” recalled Vallentyne. “We just knew he was going to be effective.”

When Schindler arrived at the site, he found the camp in an uproar. Sleeping bags and outdoor motors had been unpacked into pools of mud. The generator was too puny to power the ATCO trailer. And the cook was chasing an undergraduate student around with a meat cleaver. “He didn’t like students,” recalled Schindler. “We found out the man had a history of poisoning and starving people in logging camps. I fired him.”

Within two weeks Schindler had the camp up and running. That summer, he picked and surveyed the 46 lakes that became the famous Experimental Lakes Area.

THE WATER BATTLES

At the time, eutrophication dominated headlines by turning Lake Erie and other bodies of water into a giant soup of algal blooms. Richard Vollenweider, a researcher who looked like Albert Einstein, suspected phosphates were the problem but had little proof. The soap industry blamed carbon as the culprit, and swore suds were completely natural.

It took a few years, but by 1974 Schindler and his “mosquito bite brigade” conclusively proved that phosphates from detergents and farm fertilizers produced noxious algae blooms and smothered oxygen levels.

One of his experiments inspired awe in many scientists. The ELA team divided a lake with a large rubber curtain. They added nitrogen and carbon to both halves of the lake, but phosphates to only one half. The side contaminated with phosphates “exploded into teeming green soup within weeks.” The team then took a picture of the ecological drama from the air, which quickly made Lake 226 something of a celebrity. The photograph eventually appeared in more than 400 publications. James Elser at Arizona State University later called the photograph “the single most powerful image in the history of limnology.”

Vallentyne later threw Schindler, an introvert, into state-by-state hearings in the United States as politicians debated what to do. Whenever he had to confront the advocates for the detergent industry (Schindler called them “soapers”), he gave an authoritative presentation and showed the photograph: “And, thanks to that one picture, I usually succeeded. That one picture said things to people who knew no science.” It also improved water quality around the world.

Next came the threat of acid rain caused by the sulphurous emissions pouring from metal smelters and coal power plants. Schindler proposed a whole lake study of acid rain based on the pioneering work of Harold Harvey and his students in the Sudbury region. Even though Canada then had higher acidifying emissions than Scandinavia and more sensitive lakes, the bureaucrats accused him “of inventing and exaggerating the problem.”

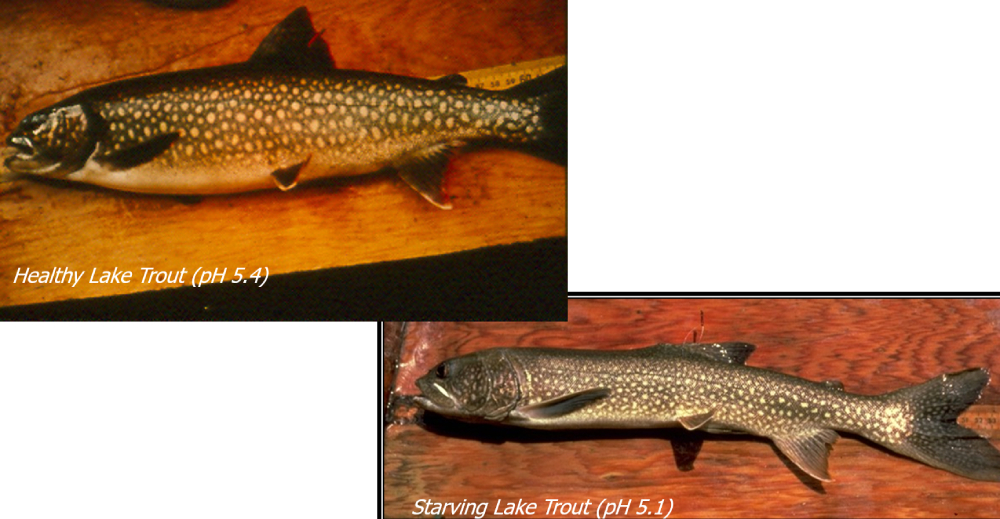

Schindler considered his acid rain research some of his finest work, and it was. By adding sulfuric and nitric acids in different quantities to boreal lakes the ELA team discovered that even very slight acidification could damage a lake’s food chain. The acids, in fact, prevented the reproduction of crayfish, crustaceans and minnows favoured by young trout. Once three or four key food species disappeared, the trout literally starved to death.

Published in Science, the study proved that everybody had underestimated the effects of acid rain on lakes.

Schindler had another dramatic before-and-after photograph to share. One showed a healthy lake trout before the acid was added to the lake. The other showed the same fish lean and emaciated. “Students gasped when they saw the starving lake trout,” said his son Daniel, an award-winning fishery biologist.

“My hypothesis was that if you killed off just a few species in a boreal lake which has on average between 300 and 400 conspicuous species, you changed the whole ecosystem,” recalled Schindler years ago. “And we showed that at ELA again and again.” In other words he proved how truly fragile the boreal ecosystem was. It didn’t have much fat to spare.

Adele Hurley, then an acid rain campaigner based in Washington, D.C., and long-time friend, remembers watching Schindler perform at a congressional committee room on Capitol Hill. All she could see was the back of Schindler’s head as he confidently addressed a room of mostly unsympathetic politicians representing the coal and auto industries.

His testimony helped to change the U.S. Clean Air Act to reduce acidic emissions. It all culminated in the Canada-U.S. Air Quality Agreement signed by Brian Mulroney and George Bush in 1991. “For decades, David Schindler walked the fine line between science and advocacy,” recalled Hurley. “He has been our Northern Star, shedding light and offering direction.”

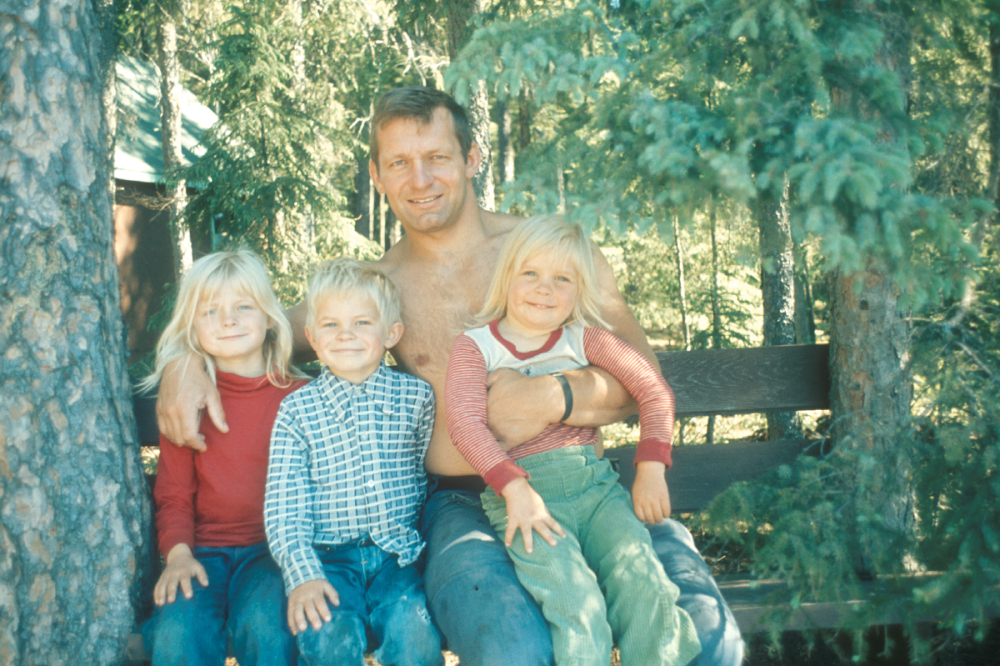

Meanwhile Schindler led a full life as a father and husband. All three of his children, Eva, Daniel and Rachel, grew up at ELA research station. His son Daniel began life in a crib fashioned from a Furuno Echo Sounder crate. His children revelled in the wild surroundings. Schindler believed that girls could do anything that guys did, and vice versa. There were no gender roles. Daniel learned how to sew (his dad even made him his first down jacket) and the girls learned how to split wood and paddle canoes. Everyone learned how to build a fire, cook and ski. “Life was a continuous adventure,” said Daniel. “He encouraged us to be courageous, fair and practical. And he liked having fun.” Not surprisingly, all three of his children grew up to become “gum boot biologists.”

But his wife Kathe, who was born and raised in Chicago, found life in the bush hard, and they divorced in 1977. Two years later he met Suzanne Bayley, a formidable wetland ecologist, at a science conference in Virginia. They married in 1980. They have been bouncing ideas off each other like paddlers swatting black flies ever since.

If anyone could keep up with a man who routinely pushed people and ideas to the limit, it was Bayley, who routinely described Schindler as a man who was “really four people trying to live one life.” She is every bit his match intellectually, and in bluntness of speech.

Schindler didn’t limit his focus to acid rain. He was one of the first scientists to defend First Nation treaty rights and incorporated traditional knowledge into all of his studies. “Dave was practicing reconciliation even before most of us understood the meaning of the word,” noted Erin Kelly, a former student and now the deputy environment minister for the Northwest Territories.

During a 1975 international conference of limnologists in Winnipeg, Schindler drew up a petition challenging Manitoba’s Churchill-Nelson River Diversion project because of its impact on Indigenous people.

The two rivers, which drain one of the largest watersheds in North America, then supported five First Nation communities and a lucrative white fish and walleye fishery that sustained them. Schindler and other scientists foresaw their demise if the project proceeded and wanted then premier Ed Schreyer to know he was conducting a deadly experiment in the boreal and violating treaty rights.

Despite strong scientific objections, the project was built with disastrous results: widespread mercury contamination of fish and the erosion of permafrost along thousands of kilometres of shoreline on South Indian Lake that may last 300 years.

He was no better disposed towards British Columbia’s Site C dam project. In a 2018 Tyee article, Schindler explained that mega-dams are falsely advertised as green generators of emissions-free energy because they strangle water systems and flood soils and vegetation, which then decompose and release methane and carbon dioxide over time.

By the time Schindler left the ELA in 1989, he had seen the boreal region transformed in the very ways he had warned about through his work. When he started there, a person could canoe for days in natural solitude. Now people and clearcuts peppered the place. Countless logging roads and skidder trails allowed snowmobiles and ATVs access summer and winter, disturbing wildlife and over harvesting fish. Trap lines were routinely vandalized. “It was like waking up with cancer every day. But it wasn’t in me but in all my surroundings.”

Schindler left the Experimental Lakes project in 1989 to take up a teaching job at the University of Alberta. The change in scene did not result in a change of pace. He immediately got embroiled in a huge political fight over the allocation of one-fifth of Alberta’s northern forests to Japanese multinationals for milling. Although he literally embarrassed the federal and provincial governments into funding a study on the impacts of pulp mills on northern rivers, the projects proceeded. Schindler concluded that in Alberta, “policy was not based on science but was expected to determine science.”

Nevertheless, much to the dismay of many Alberta’s politicians, Schindler routinely conducted applied science in the public interest. When it became evident that the Swan Hills Treatment Centre in Alberta was discharging toxins into the atmosphere, Schindler and his students took snow samples around the waste facility with the help of a local trapper. Their findings forced a recalcitrant Alberta Environment to limit fish and game for a 20-kilometre radius.

“For me, science is like eating and drinking,” Schindler has said. “I’d feel pretty empty on a day when I didn’t do any.”

Long-time collaborator Bill Donahue considers Schindler one of “the most important and effective ecologists and environmental scientists in history, not just in Canada. I’d like to think Canadians will understand and recognize that.” Jules Blais, a University of Ottawa biologist who tracked pollutants with Schindler in the Rockies, agrees. “He was an iconic figure in environmental science and fearless advocate for justice.”

Over the years Schindler accumulated more than 100 awards and honours. The Swedes, for example, awarded him the equivalent of two Nobel prizes.

Yet when he won the prestigious Stockholm Water Prize in 1992, the Alberta legislature refused to recognize the honour because of his pulp mill work. The political snub bounced off Schindler like water droplets. He once told a colleague that awards were nice but really mattered more as political tools: “They give him trust, capital and credibility. They opened doors. Powerful people returned his calls,” said John Smol.

Compounding that credibility were his unassailable ethical standards. “I was taken aback at how aggressive he was about not taking research money from oil and gas companies or timber industries for his grad students,” recalled Mark Boyce, an ecologist and fishing buddy. “It had to be clean money. That was very uncommon, and it made quite an impression on me.”

In 2000, Schindler invited me to his home in Wildwood, Alta., on the Lobstick River. After visiting the dogs, we went for a drive. “I want to show you the future of the boreal,” he said.

We got in his Subaru and headed south. We passed through a forest mangled by an assortment of roads, seismic lines, oil wells and power lines. It wasn’t a scenic tour. Invasive species like blue weed grew in the disturbances like gangrene in a wound.

Along the way we saw neither bird nor beast. We stopped at the Pembina River and walked down to its shore through a cut line marked “Danger: High Pressure Pipeline Right of Way.” The sign had five bullet holes in it. Schindler sat down on a cut poplar and said, “This is it.”

“This is what?” I asked.

“This is the future for Canada’s largest ecosystem. Unless we do something, this is the best-case scenario.”

Schindler gave the boreal another 50 years. He predicted that climate warming, clear-cut logging, air pollution and industrial development would rub the ecosystem out. With it would go the culture and history of more than half of Canada’s Indigenous people.

By his clock, today we have fewer than 30 years left.

Schindler, who always saw solutions as clearly as he identified problems, didn’t want Canada to extinguish its boreal soul. For starters, he strongly supported the 1999 Canadian Senate report The Boreal Forest at Risk, which concluded governments should set aside 20 per cent of the boreal for intensive timber production, and another 20 per cent for parks and wildlife reserves. The rest should be left alone with the preservation of biodiversity as the primary goal. But Canada is doing the exact opposite.

Schindler’s prescription included a national boreal science institute that would focus on trees and lakes. Although Canadians didn’t think of themselves as a boreal people, he didn’t think they would remain a wealthy people unless they did. To Schindler, boreal living really meant two things: “Keep it small and keep it diverse; the boreal is not a landscape that can support large populations.”

Throughout his career Schindler cultivated a special vocabulary for federal and provincial politicians who shunned scientific evidence. It included clowns, bozos, turkeys and the adjective pea-brained. He observed that Conservatives avoided science, while the Liberals just ignored it. Educating politicians about science-based policy was like playing chess with a gorilla, he said. “The game is boring, and you know you are going to win, but you have got to be prepared to duck once in a while when they get angry and take a swing at you.”

But Schindler innately built bridges, too. “He had also a knack for connecting with First Nations people — trappers and Chiefs included — for a number of good reasons, including his and Suzanne’s passion for sled dog racing and for their mutual contempt of bullshitters working for industry and especially government,” remembers veteran science journalist Ed Struzik.

“Dave had a way with words that could toss a smooth talker onto the shit wagon. I think that’s why [the late Alberta premier] Ralph Klein both loathed and admired him, and why [former deputy prime minister] Sheila Copps would phone him up late at night to get some advice on how to reform management of the national parks service.”

Sometimes he preferred to communicate via a well-executed practical joke. After an ELA colleague bought a new Kevlar canoe, the man boasted too much about its lightness. That gave Schindler an idea. He borrowed some lead sheeting left over from an experiment. Together with his son Daniel, they duct taped the lead under the seats and gunwale. The owner only discovered the added weight during a portage when the lead popped out. “I can still remember dad’s giggling the whole time we taped on the lead,” said Daniel.

One day in the late 1970s, Schindler brought home a pair of Siberian Huskies for the children. Then the kids wanted a sled. Bayley bought four more dogs. More animals followed, and Schindler and Bayley were soon entering competitive races on the weekends in the 1980s.

Sled dog racing is bit like football: you need 100 players on the roster to put 20 on the field. That meant nearly 90 dogs. Procuring food for the dogs, let alone naming them (entire litters were named after lakes, vegetables and Arctic ships) was an exercise in complexity, but Schindler considered his dogs a rare kind of inspiration.

“My mind works best while riding behind a dog sled,” he said. “I get a lot of ideas out there.” Some of his best thoughts also came while picking up dog shit. In the early 1990s he and Bayley had the best six and 10 dog teams in Alberta. They didn’t quit until they stopped winning and the snows got sparse due to climate change.

In the 2000s, Schindler probably gave more public talks than he did scientific ones. He never liked crowds (to him, five people were a crowd). But he felt he had duties to fulfill. The public had funded the science, and they had a right to know what they paid for. And he didn’t think universities earned their rent unless they engaged with local communities, rural people and First Nations. “What drives me to do this stuff is seeing all of this good environmental science lying around on shelves in ivory towers that nobody puts into practice.”

Schindler didn’t just talk about science either. He read broadly and thought philosophically. He might start a paper on climate change by quoting the Qu'ran: “By means of water we give life to everything.”

When he lifted his eyes to take in the whole planet, he cautioned, “Continued human population growth can only be done at the expense of other species, and the global biogeochemical cycles on which higher forms of life depend. Signs are all around us, in rapidly decreasing biodiversity which is decreasing more rapidly in freshwaters than in any other type of ecosystem.”

Schindler saw through political methods of dodging the ecological consequences of money-backed enterprise. He was the first scientist to criticize what he called “the impact statement boondoggle.”

The environmental impact assessment, a mechanism which now dominates most big project reviews in Canada, worked with a brutal simplicity. Politicians set aside cash for industry consultants to produce “diffuse reports containing reams of uninterrupted and incomplete descriptive data.” Enormous funds were spent with no credible scientific return. This ensured that little real science got done in the public interest. Schindler’s 1976 critique, which appeared in Science, is more relevant today than ever.

Digby McLaren, a renowned geologist and former president of the Royal Society of Canada, described Schindler as a realist who just talked about what he saw. “He is a fearless man. I love him. If Schindler sees a house on fire, he’ll tell you and that’s not pessimism. And if he is saying Canada’s house is on fire, he’s got the case to support it.”

In 2007, Schindler realized that the rapid development of the oilsands was setting Canada’s house on fire. After an Alberta Tory minister boasted that the expanding project had no measurable impact on local waterways or the Athabasca River, Schindler’s bullshit detector went off with a bang. He had read the scientific literature and knew that any large-scale clearing of watersheds always resulted in the increased erosion of chemicals. The literature also documented how the upgrading of fossil fuels and the burning of petroleum coke left a tell-tale chemical fingerprint in the atmosphere.

He assembled a team and hired Erin Kelly, his former PhD student, to do the fieldwork. His hunch resulted in two studies that left provincial and federal politicians squirming like men with their pants on fire.

The first 2009 study found that oilsands air pollution from mines and upgraders blackened the snow with thousands of tonnes of bitumen particulates and toxic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons during the winter within a 50-kilometre radius of the project. When the snow melted in the spring, the contaminants washed into the Athabasca River. The pollution amounted to an undisclosed annual oil spill between 5,000 to 13,000 barrels.

A followup 2010 study concluded that air pollution and watershed destruction by the oilsands industry annually added a rich brew of heavy metals including arsenic, thallium and mercury into the Athabasca River and at levels up to 30 times greater than permitted by pollution guidelines.

Schindler worried about the Indigenous communities that lived downstream in Fort Chip, and that depended on fishing for their nutrition, livelihood and culture. He put in endless days and weeks of work, pro bono, working with them and other northern communities to figure out ways to combat pollution risks. “We will miss him,” said John Malcom of the Original Fort McMurray First Nation. “He was a world class spokesman for humanity. If words and tears could help, I would shed a thunderstorm for him.”

In response to the oilsands findings, the provincial and federal governments promised independent monitoring, but it has since been effectively neutered by industry and the Alberta government. Now the Alberta government even wants to release the water contained in the toxic tailing ponds into the Athabasca River.

In 2012, the Harper government launched a co-ordinated attack on the country’s environmental legislation — long before Donald Trump did the same in the United States. One of the government’s key targets was funding for the Experimental Lakes Area. Suddenly a program that cost $2 million a year and that had saved the nation billions in terms of water pollution bills was no longer needed. Only a coalition of scientists and citizens saved the program from the dustbin of history.

But then the Harper government, which advocated for mining interests at home and in Latin America, attacked federal science libraries, effectively ordering the destruction of unique irreplaceable research holdings. “In retrospect, I am not surprised at all,” Schindler told The Tyee at the time. “Paranoid ideologues have burned books and records throughout human history to try and squelch dissenting visions that they view as heretical, and to anyone who worships the great God Economy monotheistically, environmental science is heresy.”

ENDINGS

Seven years ago, Schindler retired at the age of 73. He and Bayley found an old ranch facing the Bugaboo Range in the interior of B.C. The 150-acre property ran down a bank to meet the clean waters of the Columbia River. Among its willow studded wetlands, Bayley still conducts research on the impacts of climate change.

The size of the workshop sold Schindler on the property. He filled it with tools, jigs and hardwoods. There the aging farm boy continued another one of his hobbies by building handsomely-crafted furniture made of cherry and other hardwoods for his grandchild. “I liked working with cherry, and Suzanne liked the product,” he said with a chuckle. Nearly every workstation in the shop still has a piece of furniture in some state of construction. Schindler never believed in working on one project at a time.

I last saw Dave about a month ago at his home. Five years ago, he fell on some ice while walking their two dogs. He broke some ribs, and then a virus invaded his heart. The heart damage limited his mobility and energy, but it did not dim his spirit.

In the kitchen we talked about old times and friends. (I was masked and physically distant.) He noted that life goes by quickly, and moves like a wind.

I suggested that fear of the future often haunted many ecologists, but I thought his work was really driven by a deep love for the present. And I asked him where that love of water began.

He said it all started with his grandmother. His mother really couldn’t handle his energy, so she regularly packed him off to his grandmother’s place on the farm.

She let the lake country instruct the boy. Their blue waters taught him the meaning of freedom. These same waters, in their own way, selected a master student. And this student also brought fish home for dinner.

And then I said goodbye knowing I would not see him again in this world.

I told him that we might meet next time on still water on a large lake. He would be paddling through an early morning mist and the fish would be jumping. Somewhere a loon might call. And I would hail him from my own canoe.

And he smiled.

And whenever I find those peaceful waters, I know exactly what he’ll say: “Come, we have work to do.”

For 30 years, Andrew Nikiforuk wrote about Schindler and his freshwater science research for the Globe and Mail, Harrowsmith, Canadian Business, Outdoor Canada and The Tyee. His book 'Pandemonium' is dedicated to David Schindler. ![]()

Read more: Energy, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: