A single COVID-19 case can spread a long way. Take this example of a guest who attended a wedding in the Fraser Health region while infected.

The other 50 guests were exposed as a result, forcing them to self-isolate.

Fifteen of them ended up catching COVID-19. Despite the self-isolation requirement, some of them passed it on to others, who in turn spread the infection. A family business soon had five employees test positive. A person linked to the wedding brought COVID-19 to a long-term care home, requiring 81 seniors to quarantine in their rooms.

The result, from one guest at a wedding — three hospitalizations and one death.

This is just one real chain of transmission uncovered by contact tracers at the Fraser Health Authority.

Another chain began with an employee at an industrial worksite, which eventually spread to a car dealership, a medical clinic, a lumber mill and a processing plant.

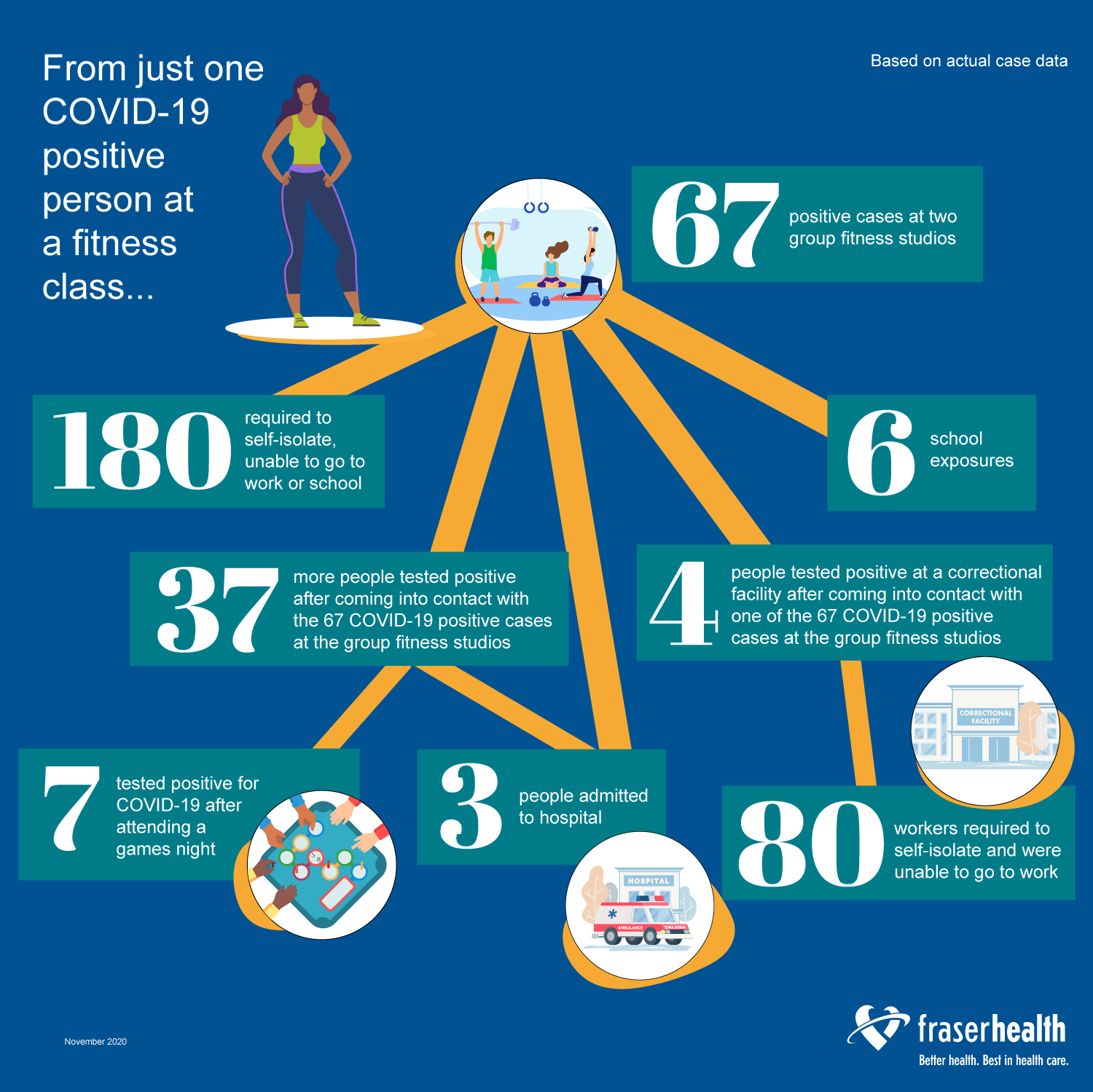

Yet another began with someone who visited two fitness studios and passed on COVID-19 to 67 others, and led 180 people they came into contact with to self-isolate. Those individuals then passed on COVID-19 to a correctional facility and eventually caused six school exposures.

For all contact tracers in British Columbia, it’s a race against time. Their goal during the pandemic: hunt down and break the chains.

“We’re working to keep up,” said Dr. Aamir Bharmal, Fraser Health’s medical director of communicable disease who oversees the health authority’s contact tracing team. “Contact tracing is an important buffer to the whole system.”

Contact tracing is the public health practice of finding the people who an infected person has come into contact with, testing them for infection, then isolating and treating them. Most tracing in Canada is done over the phone.

The strategy is used to control communicable diseases, everything from the SARS coronavirus to HIV.

“It’s really the core public health response to containing an outbreak,” said Dr. Richard Lester, an infectious diseases expert at Vancouver General Hospital and the University of British Columbia. “It’s one of the tried and true mechanisms,” he said, noting contact tracing was used in the eradication of smallpox.

The tricky thing about the new coronavirus is that someone who is positive may have a few-day lag before symptoms start to show. This means that someone who has COVID-19 may be going out and spreading it to others because they feel fine.

“In the best case,” said Bharmal, “even if someone gets tested on the first day they have symptoms and they get their results the next day, we’re already at potentially two or three days they may have exposed it to other people.”

Ninety per cent of the time, the team has been able to locate an individual within 24 hours.

Nonetheless, the pandemic has hit Fraser Health hard. The region includes the 20 cities east of Vancouver all the way to Hope. It’s home to a little over one-third of B.C.’s population and currently has 62 per cent of B.C.’s COVID-19 cases, numbering almost 15,000.

Before the pandemic, Bharmal oversaw a team of 14 communicable disease nurses.

This crew of disease detectives investigated the usual suspects like flu in care homes, and rarer ones like mumps. An outbreak of measles surfaced in the region in 2014 — the province’s largest ever — totalling 320 cases.

Contact tracing helps Bharmal’s team answer questions about a disease case: “Did someone get it from travel? Or someone else in the community?”

Early this year when COVID-19 began making headlines, the team came across some suspected cases. But the first lab-confirmed case in the Fraser Health region was found in a woman who had travelled to Iran.

It was a bad sign, because B.C. expected its earliest COVID-19 cases to be linked to China, with the first B.C.-wide case found in a man who had travelled to Wuhan. If Iran had it too, a serious pandemic was surely on its way.

“That was when we really started to intensify our actions,” said Bharmal.

The team of 14 is now nearly a team of 350. Aside from communicable disease nurses, it includes other health professionals such as physiotherapists and health inspectors, as well as aides with a minimum of high school education and some relevant experience to help fill the numbers.

The Fraser Health Authority team’s growth is in step with other contact tracers across the country, as everyone struggles to contain the second wave of the coronavirus.

Provinces are heavily recruiting for their contact-tracing teams, and the federal government is supplying what employees it can, such as workers from Statistics Canada.

B.C. is on track to hire 800 contact tracers before winter hits. Ontario has 2,750 contact tracers with another 500 on the way this month. Alberta has about 1,000, but even that isn’t enough to deal with the spike in cases. The province has since given up on contact tracing among non-priority individuals.

Overall, thousands of tracers across Canada are working to uncover a picture of how COVID-19 is making its way through communities.

“It really is a microscopic view into someone’s life,” said Bharmal. “We’re very clear that the information they share with us is confidential.... They may very well share a lot of sensitive details about where they went, who they spent time with. We need to ensure that we’re building trust.”

Bharmal adds that while the media highlights “people doing a lot of outrageous things and how that potentially contributes to COVID spread,” his team has been able to see that a lot of the time, it’s not someone’s fault that they catch the coronavirus.

“It’s made us all aware of what the vulnerabilities are,” particularly for racialized communities, said Bharmal.

Fraser Health is home to 75 per cent of the province’s South Asian population. One in five of them do not speak English, and so the health authority has been translating materials to ensure that pandemic notifications reach those communities.

There are also more multi-generational households in the Fraser region than elsewhere in B.C., and these are challenging settings in a pandemic. Bharmal heard of a situation where a member of one of these households chose to self-isolate in their car for two weeks to protect their family.

The pandemic has also highlighted how some workplaces pressure people to work while sick, as well as the inadequate housing conditions of temporary foreign workers.

For example in B.C., advocates have spoken out against the bunk rooms that seasonal farm workers reside in, with beds closer than six feet and separated by pieces of cardboard.

At the beginning of the pandemic, much of the tracing work centred in care homes and grocery stores. But as the months went by, with residents visiting more places and seeing more people, the virus has had more “points of entry.”

If a contact tracing team is able to “backtrack” to where a person got infected, such as a workplace, they might uncover more cases and help the workplace introduce new protective measures. This way, the team can help potentially prevent thousands of cases.

But the worry is that cases will spike so high that contact tracers aren’t able to keep up.

“They’re getting very stretched,” said Lester, the infectious diseases expert. “When the system is overwhelmed, we can only hire so many more nurses and health-care providers.”

Lester has been investigating how text messaging can help with patient care and contact tracing.

He’s the founder of a messaging app called WelTel, which has been used in B.C. by tuberculosis patients, mothers living with HIV, children with serious cardiac issues and remote communities on Haida Gwaii. For COVID-19, it is being used in Rwanda, Uganda and among homeless people in the U.K.

The app uses semi-automatic text messaging to stay in close regular contact with patients, followed up with phone and video calls when necessary.

“A good communication channel vastly helps to reduce anxiety,” said Lester.

With B.C. sticking to phoning patients, it is possible that human resources for contact tracing as it’s currently being done will be exhausted. A more precise approach, such as focusing on clusters, will then have to be adopted, said Bharmal.

Stricter social measures will also be needed as a line of defence.

“We are certainly in the middle of that situation,” he said. ![]()

Read more: Coronavirus

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: