Since COVID-19 spread to Canada and pandemic lockdowns fell in place, Rahil Adeli has been deeply distressed that her path towards permanent residency is in jeopardy.

“If you make a very simple mistake, you can put your situation in danger,” said Adeli, an international student who graduated from Simon Fraser University with a master’s degree in urban studies two months ago. “It’s a one-time, life opportunity.”

She is anxiously waiting to receive her post-graduate work permit, a time-restricted program issued to international students after they graduate that allows them to work as they fulfill requirements towards permanent residency in Canada.

Permits are issued based on a student’s length of study, ranging from eight months to three years, and recipients can only get one permit in their lifetime, driving up the stress towards making it count.

While the graduated students can work any job with the permit, the pandemic has severely constrained their ability to find the skilled, full-time and continuous work — often, at least a year of it — that they need to qualify for permanent residency.

Canada’s international student population has tripled over the past decade, and these days approximately one in five post-secondary students are international.

B.C. boasts the second-highest number of these students, at 144,675 and steadily rising as of 2019, according to Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada.

More than 58,000 former international students immigrated permanently to Canada in 2019 through the post-graduate work permit program.

Though she obtained an undergraduate and master’s degree in her home country of Iran and then her recent master’s degree in Canada, Adeli says the job market looks increasingly slim for her. Neither her current part-time contract, which ends in two months, nor her several roles as a research assistant throughout her degree will count towards her permanent residency.

The permit issuing process itself has also faced significant delays in recent months due to COVID-19.

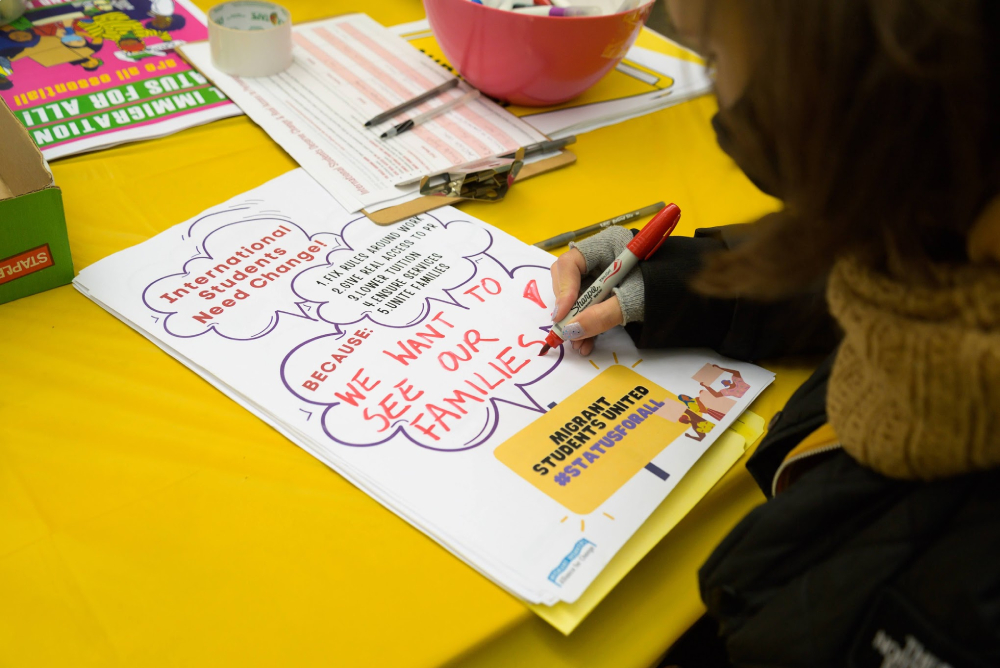

Given these realities, student activists are calling on the federal government to make the permits renewable. They say that an estimated 17,000 people across the country hold expiring permits and face deportation if action isn’t taken by the end of the year.

“Millions of people across Canada have lost work and wages, and many students, of course, are deeply impacted. But even though COVID-19 has changed everything, these unfair immigration rules are staying the same,” said Sarom Rho, the national co-ordinator of Migrant Students United, the only national representative body of this group in Canada.

On Oct. 25, Rho and other members of Migrant Students United protested outside a downtown Toronto immigration office, carrying a three-metre-high mock-permit with “Renew PGWP,” the acronym for the permit, stamped across it in huge red letters.

They wanted to “make it loud and clear that migrants should not be punished for the pandemic,” particularly not former students, said Rho.

Migrant Students United does not have an exact breakdown of people facing expiring permits by province, but Rho estimates that the number in B.C. is likely in the thousands.

In response to a request for comment, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada said that it has introduced a number of measures to assist international students and other migrant workers, including creating a process for workers who need to change jobs quickly and allowing people with visitor status to apply for a work permit without having to leave the country.

The government also extended the deadline for visitors and study or work permit holders to update their lapsed permits until Dec. 31. But these moves do not apply to non-renewable permits, like the post-graduate work permit.

“The Government of Canada recognizes that international students bring tremendous economic, cultural and social benefits to Canada and annually contribute more than $21 billion to the economy,” a representative said in a written statement to The Tyee.

The office said it has introduced a number of “facilitative measures” meant to help international students, including allowing virtual schooling to count towards an eventual post-graduate work permit application.

“[The government] will often reiterate what’s already done, and say they are looking into matters, but that’s not a real answer,” said Rho.

On Oct. 30 the federal government announced an immigration plan to support Canada’s economic recovery, promising to welcome immigrants at a rate of about one per cent of the population over the next three years.

Rather than a real show of growth, the plan compensates for this year’s decline in immigration due to the pandemic, adding about 50,000 spots to bring yearly totals to just over 400,000.

Neglecting to mention migrant students in that announcement was a major oversight, activists say.

“That was a failed opportunity for [the federal government to] ensure that all migrants and undocumented people have real access to permanent residency and full and permanent status for all,” said Rho.

Felix Otterbasch, a former international student who got his permanent residency after graduating and who has worked at SFU and the University of British Columbia in student recruitment roles, has seen many friends and students derailed by tough work requirements.

“It basically puts a burden on international students that are graduating, [wanting to take] entry-level positions that might be more in line with their interests and skills, but they don’t take it because it doesn’t meet the kind of classification that they need later down the road.”

Adeli is concerned that she will receive a one-year permit and have to scramble to find fitting employment and fulfill work requirements to apply for permanent residency before it expires.

“Now I’m thinking that I need to find a job, any job, even one that I don’t want, under any conditions, to be able to get that one-year work experience to be eligible for PR,” she explained.

The recent protest represents just one aspect of the changes that members of Migrant Students United have been advocating for. They are also asking the government to loosen the requirements for what kind of work can count towards permanent residency as well as address rising international student tuition.

Otterbasch has grappled with whether making the permit program renewable is a viable solution to the problems international students face.

He agrees that there needs to be a short-term fix, but that “post-pandemic, I think it’s more about reforming how [migrant students] can qualify to be a skilled worker.”

Migrant students, and young people more broadly, have been filling many of the jobs deemed essential during the pandemic, like working in food services and delivery. But those jobs do not count towards permanent residency either.

“With what we know about racialized unemployment, finding a high-skilled and high-wage job, even in the best of times, is difficult for migrant students. But under COVID-19, it’s nearly impossible,” said Rho.

And when students do find a job, Adeli explained, they often have to commit, no matter the circumstances.

“What frustrates me the most is that you have to stay in any job, even if you’re being insulted, even if you’re getting exploited,” she said. “Because your presence here, your eligibility to stay in the country, is tied with the work that you’re doing.”

The government is not morphing quickly enough to fit the changing economy, Otterbasch noted — for instance, many new graduates are working gigs or contracts to make ends meet, work that isn’t eligible under the post-graduate work permit program.

To solve these issues, Rho said, the government needs to take action sooner rather than later.

“Every day that passes without response means that time is running out.” ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Education, Coronavirus

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: