Several years ago a team of people at Providence Health Care in Vancouver, inspired by the work of a famous author and doctor, decided to rethink how to speak with patients and their loved ones when the person’s odds of living much longer were low.

The aim was to educate doctors on how to listen closely to what patients most feared and desired in their final days, and then how to plan together the next steps.

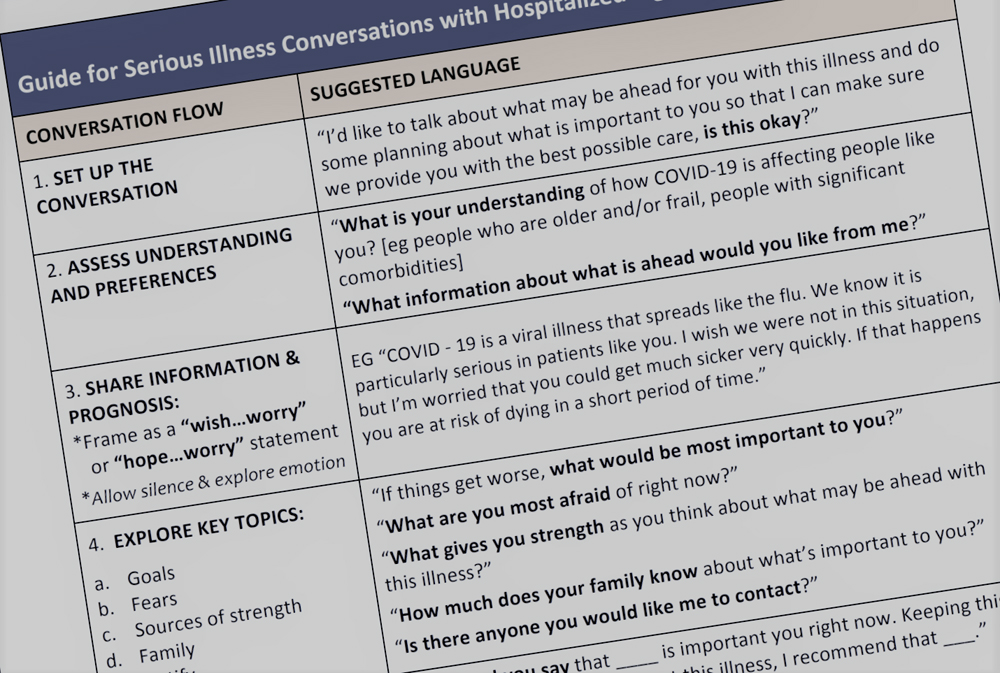

The fruit of that labour is a guide for talking with patients seriously ill with COVID-19, highly sensitive discussions that will increase as the pandemic fills hospitals.

Wallace Robinson, the advance care planning lead at Providence Health who helped create the guide, says it “is continuing the type of conversation that we’ve been advocating for, that puts the patient and the family at the centre of the conversation.”

Conversations about death and dying are difficult, and even more so because our culture is so averse to them, said Robinson. Doctors often have trouble broaching the subject, and find themselves ill-equipped to start them in a way that feels constructive, research shows.

“There’s a culture in medicine that views death and dying as a failure of our practice,” said Dr. Lauren Daley, a palliative care physician at Providence Health. “Facing that is hard.”

And this difficulty, Providence began to realize, meant that patients without a likely chance of meaningful improvement were dying in the intensive care unit, after undergoing more duress from rigorous treatment.

Drawing from the ideas of surgeon, Harvard professor and writer Dr. Atul Gawande, author of Being Mortal, Robinson’s team began building a framework for health-care providers to approach serious illness conversations in 2016, including Gawande’s script for speaking with patients and their families.

The strategy focuses on a patient’s goals for care, which could include spending time with family, managing symptoms or not being admitted to the ICU unless there was a meaningful chance of recovery. It also became mandatory for physicians to have these conversations.

From there, a doctor comes up with a care plan to align with the patient’s goals and shares their recommendations with the patient.

“The real beauty of this tool for me is that it focuses your language in a way that is human-centred and person-centred,” said Daley. “You see your patient as an expert in their own life story.”

As the coronavirus pandemic began to grow, Robinson’s team adapted their approach to create a guide to critical illness conversations in the context of COVID-19. They imagined some users might be younger or trainee physicians who may be called up to provide care should it be needed.

“It’s adapted in a way that recognizes that for a particular subset of the population, critical care interventions will cause harm and suffering without providing meaningful benefit or allow a person to survive this disease,” said Daley, noting the adapted guide is focused on the elderly and the medically fragile who may have more complicating health factors.

The goal of the guide is to help physicians clearly communicate likely outcomes and options, including when intensive care would likely only prolong suffering or the dying phase of a person’s life.

Patients on ventilators may be placed in a drug-induced coma, never to emerge if they are too sick. Intubation and ventilation are both painful and extremely uncomfortable, and could cause further distress if a patient’s body is unable to meaningfully recover while their breathing is being assisted.

Providence Health Care operates St. Paul’s Hospital and Mount St. Joseph’s Hospital in Vancouver, and a number of other facilities in B.C.

Its team’s work has been lauded by Harvard-based Ariadne Labs, a brainchild of Gawande, and others across Canada. “This is a movement in health care that we’re a part of at Providence and in B.C.,” said Robinson, noting Providence’s collaboration with Vancouver Coastal Health and other critical illness advocacy organizations.

He is unequivocal that conversations around care plans are not a strategy to ration resources or beds should it ever come to that. Those are two very different conversations, Robinson said.

“I think this conversation helps us focus on doing the right thing for the patient,” he said. “And if there gets to be a time where we don’t have enough ventilators, that’s a whole separate conversation.”

Serious illness conversations are increasingly essential as the speed with which care decisions need to be made in critical cases of COVID-19 leave many patients and families otherwise unprepared.

“There are so many people out there that cannot have these conversations,” said Virginia Garossino, an advocate for critical illness care. “And this crisis now is forcing people to start thinking about what happens if they need to.”

Garossino became an active volunteer and donor to St. Paul’s Hospital around these issues because she and her husband, Dick, craved these conversations with doctors in the last years of his life.

Between his death due to complications of dementia in October 2014 and his diagnosis 15 years prior, there were only two relatively brief conversations with physicians about how critical his illness was.

“What we missed most was a meaningful conversation,” said Garossino, noting she and her husband were comfortable discussing what they wanted in death and made their own plans. “It’s that emotional connection (with the doctor) that is so important, and we didn’t get it.”

Their planning as a couple allowed Dick to pass away at home, surrounded by family. And Garossino wants everyone in such a difficult situation to be able to achieve the same with guidance from a physician.

“Once you get into the conversation, it’s not scary,” she said, noting that patients should also be discussing their wishes with family in case someone else is charged with making these decisions. “It’s their life. They should have a say in how it ends.”

Advocates like Garossino and patient partner Karen Sanderson have been instrumental to the continuing improvement of physician education for critical illness conversations.

The programming has now trained hundreds of doctors and touched many more lives, but it’s not a finished product. It continues to evolve and adapt as new learnings come to light.

“This conversation changes everything for the better,” said Sanderson, whose own serious illness and the deaths of her parents drove her to volunteer to educate physicians on these topics.

While the pandemic crisis is putting immense pressure on families and the health-care system, Robinson hopes it might also help transform the taboo culture around advance care planning.

And perhaps that could help people get more of what they want out of life while they are in good health.

“Maybe this pandemic is a time when that culture shifts, when we are as a society more open and aware that we are vulnerable, and to think about what our goals and fears might be,” said Robinson. “It’s a sobering time, and maybe we’re reflecting on, ‘What is most important to me about my life?’” ![]()

Read more: Health, Coronavirus

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: