The B.C. government’s response to past wrongs against Japanese Canadians should focus on building a stronger society, not helping individuals, says a new report based on consultations across the province.

Lorene Oikawa, president of the National Association of Japanese Canadians that coordinated and published the report, said education could help ensure no other group could face similar abuses.

“If we know our history, we won’t fall for the rhetoric some of the haters want to spread,” she said. “We don’t want anything that ever happened to our community to happen again to any other Canadian of any ethnicity, any orientation, any reason to ‘other’ another group and do that.”

The 36-page report, Recommendations for Redressing Historical Wrongs Against Japanese Canadians in B.C., is based on consultations between April and September, with funding from the provincial government.

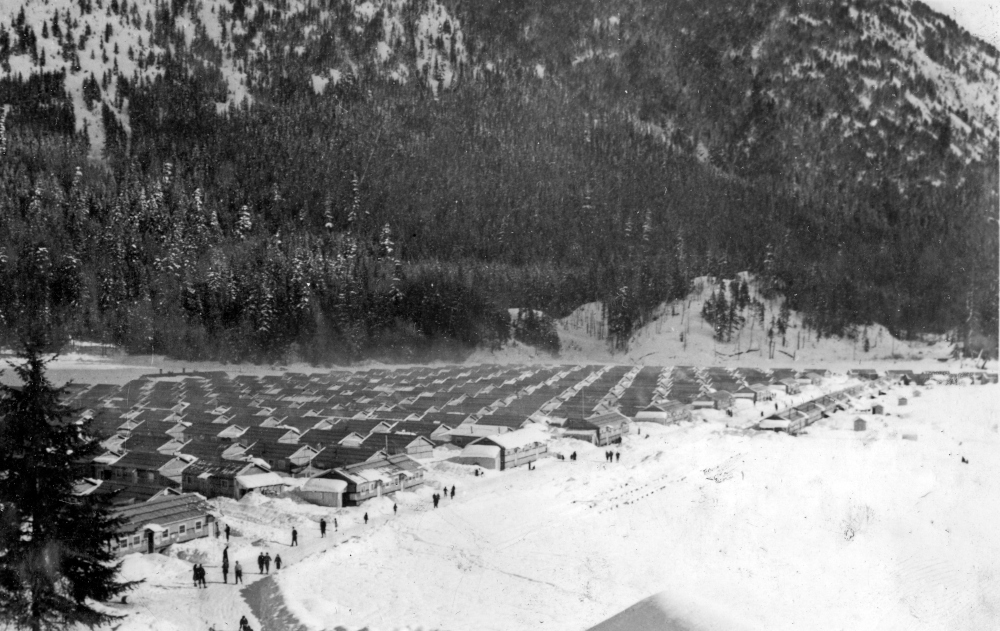

“This report is important, because it’s the voices of our community,” said Oikawa, whose parents and grandparents were among 22,000 Canadians of Japanese descent treated unjustly during the Second World War. The Canadian government took their land and property and incarcerated them in internment camps.

The report recommends the provincial government:

-

Enhance education in B.C. public schools so that every student and teacher learns about Japanese-Canadian history;

-

Take concrete steps to combat racism and discrimination, including creating an independent body to work with community groups to assess the province’s anti-racism strategy and develop programs, services, resources and policies to counter hate-motivated actions and speech;

-

Declare a commemorative day and provide funds for memorial sites, museums and monuments to raise public awareness;

-

Create a legacy fund for the Japanese Canadian community to develop programs and activities and address needs, including housing for seniors, scholarships for students and rebuilding communities; and

-

Deliver a formal apology, worded in consultation with the Japanese Canadian community, for the premier to deliver to acknowledge the B.C. government’s role in the wrongdoing.

There was a federal apology in 1988 that came with payments of $21,000 to survivors, far short of compensation for the value of land and property the government had taken.

The B.C. government offered an apology in 2012, but Oikawa said the community never accepted it.

“In 2012, the Japanese-Canadian community wasn’t involved in that apology, and there wasn’t any meaningful follow up. There weren’t any actions following from the apology.”

Meaningful action is what the community wants now, she said.

Tourism, Arts and Culture Minister Lisa Beare said she welcomes the report and was moved by the people who spoke while delivering it to her.

“This was a fantastic opportunity to have a conversation with the Japanese community about the historical wrongs that their community faced,” she said. “We’re going to take the time to study [the report] and then work with the community together to create a path moving forward.”

Asked if the province would fund the memorial projects and legacy fund recommended in the report, Beare said it was too early to say. “We just received the report so we’re just now taking the time to look at it, but we’ll work with the community to figure that out.”

Mary Kitagawa is an 85-year-old Tsawwassen resident who last year received the Order of B.C. award for her advocacy for human rights. Her personal story was included in the report.

Its recommendations are deliberately wide-ranging, she said.

“It’s not for individual things. It’s for the community, because it’s the community that suffered. They obliterated the Japanese-Canadian community from British Columbia, and it’s for the community that we are fighting for.”

Kitagawa was seven when she and her family were removed from their property on Salt Spring Island and incarcerated. Her story tells of RCMP officers forcibly taking her father away, weeks spent in animal barns with no toilets, a series of horrible shacks, and forced labour.

“When the war started, everything was taken from [my parents and grandparents],” she said. “They literally stole our land and everything that was in our house.”

While the loss of property was unjust, there also needs to be attention to what else was lost, she said. “Many of the other things that we lost, like education, our friends, our community, our dreams, our plans, things like that, were very, very important... Those are the intangibles that no one talks about.”

Money for individuals wouldn’t repair those losses, she said. “How are you going to pay anybody any amount of money for seven lost years? I lost my childhood. My sister lost her childhood too, and lost her education.”

Provincial politicians were responsible, Kitagawa said.

“They said that we had to be moved because we were a security threat, but that was a false narrative,” she said. “The RCMP and the military were keeping surveillance on all the Japanese-Canadians from 1937 on. They told the government there was no fear of any sabotage from the Japanese-Canadian community.”

Accounts from the time make it clear that B.C. politicians saw the war as an opportunity to dispossess people of Japanese descent, she said. “It was really the B.C. politicians that pushed for uprooting us and getting rid of us from British Columbia.”

It wasn’t until April 1, 1949, four years after the war had ended, that Kitagawa and other Japanese Canadians were finally free.

The government will move slowly like governments do, but the report offers a specific redress plan for it to consider, said Kitagawa, who was successful a few years ago with a campaign to get the University of British Columbia to recognize Japanese Canadian students forced to leave the school during the war.

“It takes a long time, but you can’t give up,” she said. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, BC Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: