The RCMP’s dismal record in complying with access to information laws has prompted an investigation by the Office of the Information Commissioner.

The agency’s annual report confirmed the investigation into how the RCMP is “meeting its obligation to provide timely access in light of information gathered during various investigations.”

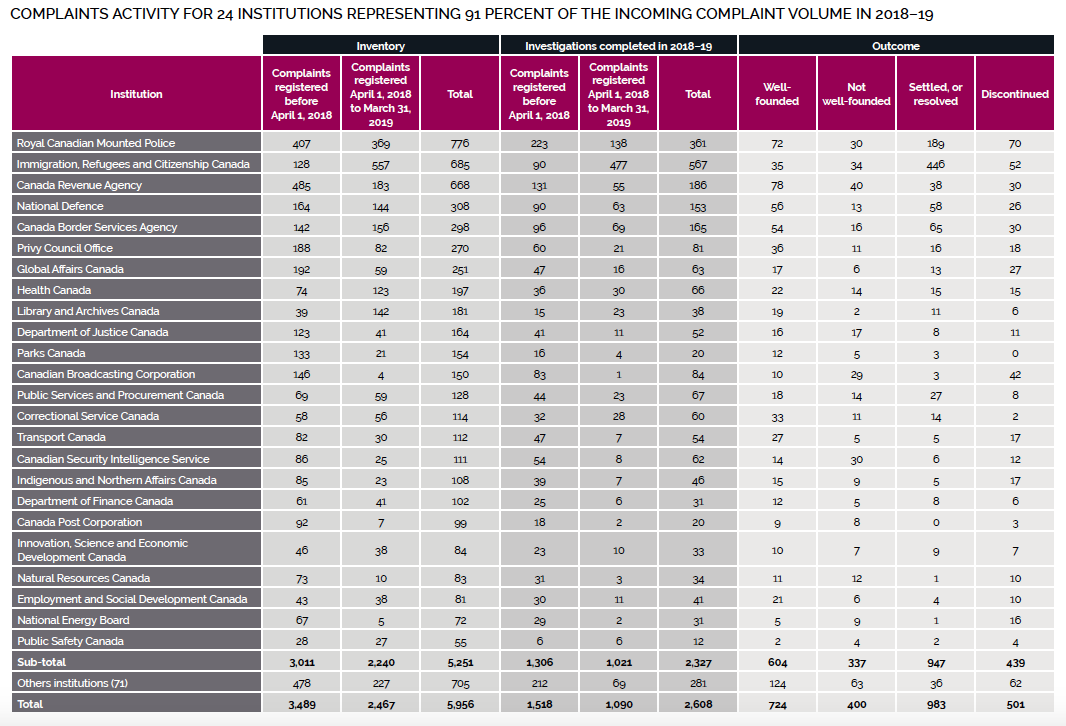

The RCMP has drawn the most complaints for failing to comply with access to information requirements of 24 agencies and departments, the report revealed, followed by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada and the Canada Revenue Agency.

The commissioner’s office said it can’t comment on the ongoing investigation of the RCMP.

A Tyee investigation has found the RCMP’s failure rate in complying within timelines set by the Access to Information Act has tripled over the past four years.

The act requires federal agencies to provide requested information within 30 days. If they can’t meet the deadline, they are required to notify the person or organization seeking the information. If the expected delay is more than an additional 30 days, they’re required to notify the Office of the Information Commissioner.

But the RCMP failed to notify people requesting information that it would miss deadlines in almost two-thirds of cases in 2017-18. Its failure rate has jumped from 15 per cent in 2014-15, to 64 per cent in 2017-18.

And between 2014 and 2018, the RCMP went from completing three-quarters of its access to information requests on the original 30-day deadline down to less than one-third.

The number of access to information requests remained relatively stable during that period. And the number of staff devoted to processing requests grew by more than 50 per cent.

The failure to notify means that those who sought the information — news media, individuals and others — may get no response for months.

The commissioner’s office may also not become aware of repeated failures to comply with the act until year-end reports.

Long delays, failure to notify the norm

The Tyee filed an access to information request on March 28, for example. The 30-day deadline for a response or notification of a delay passed without any response from the RCMP.

Three weeks ago, the RCMP alerted us that it had only then assigned an investigator to review the request — almost five months after the original deadline for responding. It noted informally that we can file a complaint with the information commissioner, which we had already done.

Since then, we’ve asked what progress has been made and when the information could be expected.

The RCMP stated that it was “unable to assign an analyst to review the records as there are over 5,000 pages.”

Many other government departments, in addition to following legislation and notifying people requesting information of delays, will work proactively with requesters to provide an ETA and look at ways to refine the request to allow records to be produced more quickly.

The formal complaints against the national police force top a list of 24 institutions. At 776 complaints, the RCMP total is greater than the combination of all remaining 71 institutions at 705.

The Office of the Information Commissioner investigated 361 of the complaints against the RCMP in 2018-19. More than half — 189 — were later settled or resolved.

Of the remaining complaints, 72 were determined to be well-founded, the second-highest tally next to Canada Revenue Agency at 78. Only 30 complaints were determined to be without merit.

Increasing staff while delays worsen

The RCMP claims in its reports to Parliament that the failures to comply with the act are due to “workload.” In its most recent report, it blamed 98 per cent of the 2,047 cases where it failed to meet legal deadlines on workload.

However, in the last three years the number of access to information requests to the RCMP only increased 15 per cent, while the RCMP reported full-time staff hours devoted to administering the Access to Information Act jumped by more than half. The number of staff increased from 22 to 34.

RCMP spokesperson Cpl. Caroline Duval stated in an email that the small increase in access to information requests doesn’t tell the whole story.

The work became more time-consuming after the government introduced reforms aimed at increasing access in 2016, she said.

“The elimination of search fees in May 2016 has directly contributed to... the institutional ability to meet legislative requirements,” the statement said. There was an increase in “complex requests,” she said.

In fiscal year 2016-2017, the RCMP’s access to information branch saw a 150-per-cent increase in consultations from other government departments and a 330-per-cent increase in the number of pages required to be reviewed, Duval said.

The force has held training sessions for 1,200 personnel across the country aimed at improving service standards, she added.

Police resisting public’s right to know

Sean Holman, a Tyee contributor and associate professor of journalism at Mount Royal University in Calgary, is writing a book on the history of freedom of information.

He said the RCMP’s worsening record may represent a return to secrecy in government, especially around policing.

“The RCMP and law enforcement in general in this country have always been opposed to freedom of information,” Holman said.

A 1978 document by the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police law amendment committee shows an attitude that continues today, he said.

It argues “those who have cried the loudest about the abuse of secrecy are not the underprivileged or the subjects of potential abuse, but rather individuals and groups actively supporting greater individual freedom with an apparent lack of concern in understanding of the impact of the proposals on society as a whole.”

The police chiefs’ report claims that people advocating for access to information “are quick to maintain their individual rights and hold themselves up as champions of the minority and underprivileged, but their recognition of duties and attendant obligation towards society is solely conspicuous by its absence in their representations.”

The need for access to information laws “would appear to exist only in the minds of a few who wish to justify new social concepts,” the report says.

There was always a resistance to openness, said Holman. That’s partly justifiable when it comes to concern for protection of investigations or police sources.

But he’s concerned that police in Canada use freedom of information laws as a shield against accountability instead, as a way to helping citizens understand what police are up to and hold them to account.

The decline in traditional news media and reduced number of reporters has made it easier for police to keep information secret and ignore access to information laws, he said. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: