When you see and click on an ad on Facebook you might make some assumptions about your privacy — indeed they are guaranteed by Facebook itself.

You may suppose you are one of a large group of people who happen to share certain tastes, who Facebook has helped advertisers find. But your personal identity is hidden. Surely your name and other identifying traits are no business of advertisers. And they could never successfully create a Facebook ad with the aim of targeting you alone, specifically.

If that’s been your belief, read on and learn about a loophole in Facebook’s system that could have allowed advertisers to narrow their targets down to exactly one person — maybe even you.

And if they did that, they may have violated privacy laws. Such regulations in Canada and beyond are a reason Facebook doesn’t make this ultimate form of micro-targeting part of its business model.

Let’s start with why Facebook can claim that as a user you can see ads and even click on them, but the advertiser can’t know who you are.

Facebook ensures that privacy by requiring ad campaigns to reach a large enough audience — a minimum of 100 people — to prevent advertisers from targeting specific individuals, the company says. And when Facebook gives advertisers statistical reports on their campaigns, it withholds the identities of users who saw or clicked on ads.

But The Tyee discovered that Facebook’s measures have not delivered the privacy it promises, thanks to a known security flaw the company did not address between at least 2017 and Feb. 21 when The Tyee last tested and presented the issue to the company.

Facebook admitted the issue to The Tyee after we reported to the company, and claimed yesterday, March 5, it has now been fixed.

The flaw has allowed ad campaigns to launch with a single target rather than the audience of at least 100 Facebook officially requires. This means that advertisers on Facebook could know when you, personally, were viewing and clicking their ads on the platform.

Isolating you as an identified ad target also means an advertised website you click to from Facebook could know who you are, from the moment you land to everything you do or enter on the site, contrary to Facebook’s assurances.

Tobi Cohen of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner told The Tyee that although the government had ongoing investigations into Facebook, it had not looked into this issue enough to say if it violated the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act.

But Cohen’s agency has poured effort into similar investigations, finding Bell Canada, for example, had delivered ads in a way that could have allowed advertisers to identify the Bell customer. Bell ultimately agreed to shut down the program.

“I find this deeply troubling” said Charlie Angus, an NDP MP and vice-chair of the Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics of the Facebook ad targeting loophole.

“It seems to violate Facebook's own terms of service,” said Angus, “or at least, circumvents the intended use of the feature, which many terms of service prohibit.”

If it does violate Facebook’s terms of service, it also violates the consent principle of PIPEDA, said Angus.

“Users did not consent to give their information to advertisers in this way,” he added.

Facebook did not reply when asked whether it would notify anyone that had been targeted using the security hole.

“If we have evidence of this, I will be asking the privacy commissioner to launch an immediate investigation,” said Angus.

How does it work?

Facebook allows businesses to provide their own lists of identified people as leads using its “custom audience” tool, and target them with ads that show in social media feeds.

It tries to match provided emails, names, phone numbers and/or internal Facebook IDs to targets using the social network.

Facebook prevents advertisers from knowing which leads were found on the social network, and the identity of anyone who clicks, by requiring each ad to target groups of a minimum size — Facebook’s documentation says 100 people.

A Facebook spokesperson admitted to The Tyee March 5 that the loophole “caused a situation where an ad could have been delivered to an audience below our minimum size” and this would have enabled businesses to send ads to just one person.

Warnings were there

As long as two years ago, others wrote articles that might have alerted Facebook that its custom audience tool was flawed and allowed targeting of individuals with known profiles. Nothing stopped advertisers from exploiting the flaw. In fact, the flaw was published in 2017 on Medium by Michael Harf, whose LinkedIn profile says he runs a company called “Digital Results” in Johannesburg. Harf would not answer Tyee questions about the method he advocated.

“Facebook allows you to target a whole range of audiences (either by interest group, customer list and many more),” Harf says in the piece.

“But there is an interesting potential if you some sneaky Facebook hacks which enable you to target a much smaller group of individuals and even one individual if you wish [sic].”

Essentially, advertisers upload a list (20 people are adequate, Facebook admitted, in spite of Facebook’s advertised minimums of 100), and then exclude all but one person from the ad using means such as gender.

The advertiser could then know exactly who has viewed or clicked ads and landed on their website. The Tyee tested the technique and confirmed it worked.

Advertisers could also design a hyper-customized ad to influence someone, where the person would think the ad was shown to everyone in a particular demographic.

Sites advertising techniques to circumvent Facebook’s weak measures are confirmed to have been viewed thousands of times over years by advertisers aiming to “sniper target,” as Harf called it.

Facebook said it was not aware of any malicious use of the technique.

How The Tyee proved Facebook ads could target a single person

In February, The Tyee reported the issue to Facebook’s security researcher, having successfully launched a campaign using a similar technique. Facebook’s researcher denied the ad would deliver with using such a small audience. He closed the issue.

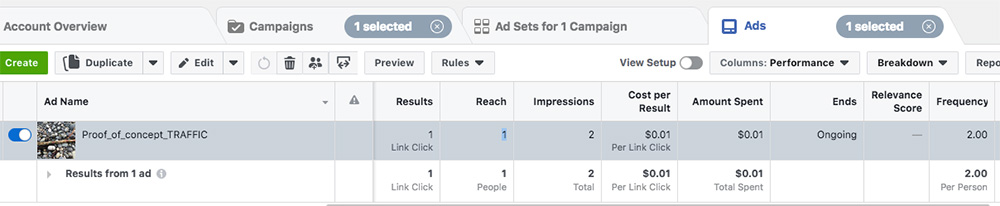

So we placed an ad, raised the bid to a highly competitive price and set it to deliver as often as possible. It delivered, twice, to our only target (our own test account), and nobody else, as the technique predicts.

What difference does this make to you?

If you happened to be our target and, say, filled out an anonymous personality test or answered a health survey on our site, thinking you were protected by Facebook ad anonymity, you would be wrong. We’d know all about your answers.

We submitted our test results, and Facebook reopened the issue while they checked with their ad team to see what we were experiencing, its researcher said.

Why would someone want to do this?

Any advertiser that floats an ad into your feed on Facebook may have targeted you by your email or phone number in the first place. So why not just email or call you instead of going to the trouble of finding you on Facebook?

Beyond the obvious reasons — a captive audience, the ability to beat past spam filtering, advanced targeting — a Facebook feed provides a veil of seeming anonymity, based on expectations Facebook has fostered.

In fact, Facebook has a team that vets all of its ads for compliance with legislation, and it is supposed to keep ad interactions anonymous.

An illustrative case of inside baseball

The Times in the U.K. reported, from a book, how Labour party campaign chiefs hoodwinked their own boss, Jeremy Corbyn, by "micro-targetting" ads made to persuade the political figure and his closest aides, in this case of a relatively innocuous falsity: that the ads they were viewing weren’t made just for them.

They wanted the boss to think they were running ads, as he requested, to all of the U.K. voters, too. But the campaign workers found the messages were too far in left field to resonate, so they simply pointed the ads at Corbyn himself and other brass that were watching out for them. They then blasted more middle-of-the-road ads to the rest of the electorate — but not to Mr. Corbyn — and lost the election.

An article covering the Times report quotes from Labour communications director Tom Baldwin’s book, identifying a purpose of the custom ads on Facebook: there’s a tendency to assume they aren’t just for you.

“If it was there for them [Corbyn and his associates], they thought it must be there for everyone,” an unnamed Labour Party official said to Baldwin. “It wasn’t. That’s how targeted ads can work.”

But the publication calms its readers by pointing out a familiar refrain in the next sentence:

“The tool cannot target down to a literal individual and requires at least a couple dozen people for a campaign to run.”

The author of the article did not know that all but one of the names can be dupes that will never see the ad. Ironically, however, the article links to one of many websites (the one linked to earlier) detailing precisely how to bypass this requirement, to target only one person.

Should you be worried? It depends on what you believed about Facebook.

Whether this matters to you likely depends on what your expectations were of the Facebook platform. If you thought that Facebook adequately protected advertisers from knowing who it is and what you do next when you clicked on an ad that appeared on your feed (as its guidelines to advertisers suggest), then you were wrong.

If you were cynical enough to assume that Facebook ads, just like any targeted ad delivered to your regular old email, could allow advertisers to determine exactly who is viewing, clicking and landing on their site, your distrust was justified this time.

But even if you are a sophisticated cynic who assumed the worst or doesn’t use Facebook at all, perhaps you should still worry about the 84 per cent of potentially voting Canadian adults who do, and what other new massive experiments in manipulations of democracy we’ll learn they participated in, most likely long after votes have been counted.

This Facebook privacy hole was just the latest to be found by The Tyee, and it was sitting in plain Google sight, for at least two and a half years. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Media, Science + Tech

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: