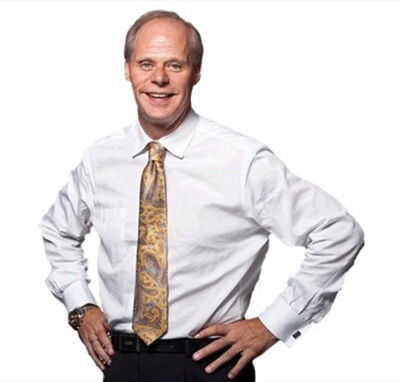

On Dec. 3, Dan Carter was sworn in as mayor of Oshawa, a city of about 170,000 people northeast of Toronto. He wore a grey suit and pale silver tie as he dipped his head to accept the chain of office.

It was a long way from his years of addiction and homelessness.

Carter, like many people who experience homelessness, had been through the foster care system. He was adopted at the age of two. In his teen years, he fell into addiction. An undiagnosed learning disability left him functionally illiterate. It wasn’t until his sister convinced him to enter rehab at 31 that he was able to get his life back on track, build a career in broadcasting, as a regional councillor, and now as mayor.

He spoke to The Tyee about how his life experiences have informed his views of politics and what he plans to do to address homelessness in his city.

The following interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

The Tyee: What were some of the factors that led to your experience of homelessness?

Dan Carter: Addiction was number one. My addiction to drugs and alcohol played a significant role in every action and every impact on my life. I was a severe alcoholic, a drug addict. Basically, I started drinking and taking drugs when I was 13 and I quit when I was 31.

My addiction pushed my family away, my friends away, made me unemployable. I always say that addiction made me mentally, physically, financially, spiritually, bankrupt, in every aspect. And once I was able to get into recovery, and those kinds of things, that’s when I was able to start having a path forward. But addiction was the number one.

What was the experience of being homeless like for you?

Horrible. It was absolutely horrible. If you’ve never experienced hunger you should try and not eat for three days and then see how well you think, you act, you behave, you correspond with friends, family, partners, whatever.

Your personal reflection upon the things that created the environment you find yourself in is absolutely terrible. I always say to people if you’ve never experienced hunger, you only need to experience it once and you understand you never want to experience it again. If you’re homeless, you never want to experience it again.

You know, people think that homeless people and people that you see on the streets that are struggling, that they’re weak people. And I say, to the contrary, I think they’re very strong people. Because to live in that kind of environment, by yourself, not living in a conditional world, never knowing what’s going to happen next, what’s going to impact your life, it’s horrible, it’s absolutely horrible.

What was your first step on your journey out of homelessness?

My first step out of homelessness and being displaced and everything else was the opportunity in recovery. That was the only thing that was able to save my life and create new pathways. If it wasn’t that I had the opportunity to get into recovery, you wouldn’t be speaking with me today.

That allowed me to, one, realize that I was in a lot of trouble and I was very, very sick and, two, that I still had somebody that cared tremendously for me that helped me get into a treatment program and was able to give me the chance to see if I could recover from my addiction to drugs and alcohol and then deal with all the events that had taken place in my life.

Was politics something you always saw yourself getting into?

There was a natural curiosity about politics. My father worked for the federal government as a property agent. When I was a young boy the only connection piece that me and my dad had — because my father was so much older than I was, because he was my adopted father — was that he used to listen to a radio show, Pierre Berton and [Charles] Templeton. And they would talk about the issues of the day, and me and my dad would sit at the kitchen table at 10, 11 or 12 years old talking politics.

It was a connection point between me and my dad. I couldn’t build anything, I wasn’t handy, I didn’t have interest in cars, but it was a connection point. And I think that that’s where my original interest in politics came from, just those really fascinating conversations about why people do what they do. And I think that seed was planted 50-plus years ago.

It’s the one thing that my father, I think, would be proud of today, if he was still around. He would be really proud that those kitchen table discussions turned into me being the mayor of the city of Oshawa.

How has your experience of homelessness informed your perspective as a politician?

You have to understand something. I sit here today with amazement that I got this opportunity. Twenty-eight years ago I was a severe alcoholic and drug addict, who was broken in every aspect. And 28 years later I’m fortunate enough to be a mayor of a great city like the city of Oshawa. And I sit here and I think to myself, what a true blessing my life has turned out to be. Based upon the path it could have gone.

If it wasn’t for recovery, if it wasn’t for forgiveness, if it wasn’t for hope. If it wasn’t that my family gave me a chance to actually see that I had changed, if it wasn’t for people that I had lied to and that I hurt. If they hadn’t given me a chance, I would have never had this chance.

But that’s why I’ve spoken so publicly about this all across the country. We’ve got millions of people in this country who are suffering from addiction or a mental health issue and family members who are just desperate to see that their loved one someday may recover. The greatest thing that I can do is to be able to demonstrate that recovery is possible, that forgiveness is possible, that we can redeem ourselves, that there is always hope, and that we can achieve amazing things because of the experiences we’ve had.

When people talk to me about sexual assault I understand that because I was raped when I was a kid. When people talk about losing a parent I understand that because I lost my parents. When people talk about losing loved ones, I lost my brother when I was 13, he was a police officer. My sister lost her life through suicide. I didn’t learn how to read or write until I was 31, because I grew up in a school era that said if you couldn’t do the work you weren’t entitled to be in the classroom.

And it’s out of those experiences that gave me empathy and sympathy and, I hope, a compassionate heart and mind. And I believe those experiences were not there to punish me but were there to prepare me to be able to serve in this role.

What do you plan on doing to address homelessness in the city of Oshawa?

I work in Durham Region Non-Profit Housing, and we’ve made massive changes in our social housing and supportive housing file because I’ve been there. We’ve got a jobs program at some of our housing sites. We have a thing called “Connected for Success” which is $9 internet for all of our tenants.

We’ve been meeting with tent city representatives to say what is it that you need from me, how can I help you, what are the struggles you’re going through? Some of the people in our tent cities are not individuals who have drug problems, but they have mental health problems. So I was able, six months ago, to get a mobile health unit on the streets: a health care provider; an addiction worker; and a social service worker out there. I was the one who spearheaded that, got it funded, got it out on the road. We’re expanding that program now into other parts of the community.

I’m working with housing providers to be able to come up with single-room shelter concepts with wraparound services that are available. I’m out there talking to funders to be able to raise dollars to be able to build these kinds of communities. I’m out educating the public in regards to what our homeless population is facing.

And I’m going to continue to be able to look at expanding services for our homeless population until nobody’s homeless. Plain and simple as that.

What is the role of of government in combating these kinds of issues?

Government’s got to do what they do. We have to advocate, lobby, educate, we have to be the voice, make sure the voice of the people is heard, loud and clear. We have to make sure resources, monies are allocated. We’re going to have to make hard decisions and difficult decisions.

I’m frustrated that some are making the decision about the guaranteed income, that it’s not something [we] should support or move forward with. I’m a great believer that we know what poverty is, we know that if we give people more money to live on that they’re able to have better health indicators, better living conditions. Every quality of their life improves. We know that. We absolutely know that when we give more money to people that are economically challenged they don’t get on a plane and go to Florida, they spend it within a five-kilometre radius. And that changes the local economies.

You’re a conservative. I think that’s not something people necessarily associate with the sort of thing you’re talking about here. How do you reconcile that?

I grew up in a conservative house. [Laughs]. The truth is, I really am one of these people who really like making sure that we live within our means, but I also have a socialist heart. But you know the stupid thing is that we always think that we either have to be Conservative, Liberal or we have to be socialist or NDP or something. And I say, why not be a combination?

If I’m going to be a conservative and think about using dollars properly, then why can’t I say the economy will do better if people have more money to be able to spend? And their quality of life improves when they have guaranteed income. And as a conservative I can defend that because that means more people are paying tax, that means more people are back working, that means the economy is stronger, that means we can live within our means, we can put dollars into different programs.

I don’t just look at it as one dimensional, I look at as multi-dimensional. And that’s why I think I could never run either provincially or federally, because where do I fit?

It’s a unique position that you’re in, having come from a background in which you’ve experienced homelessness, and now being in position of political leadership.

When Jim Flaherty was stepping up into federal politics [in 2005], I was asked to run provincially in his seat in Whitby, Ontario. And at the time, the [Ontario Progressive Conservative] leader was John Tory. And John said, ‘Dan, I think you should do it.’ We were about to announce. And then they came to me and said, ‘Dan we need you to step aside because Christine Elliott [Flaherty’s wife] really wants a seat.’

And my argument back to them was, I understand that you believe that she would be the right person, because she’s a lawyer and she’s Jim’s wife, and she’s a smart person, and everything else. But I said to John Tory and anybody that would listen, ‘You need more people like me, not less people like me.’ And that was my message. And I truly believe that.

Do you think that most of the population can relate to people that have got it all together, great education, stable home, strong background, or do you think more and more people would be able to relate to people who have had major struggles in their lives?

Dear readers: Comments are closed over the holiday break until we return in 2019. Thanks for all the thoughtful comments this year! ![]()

Read more: Politics