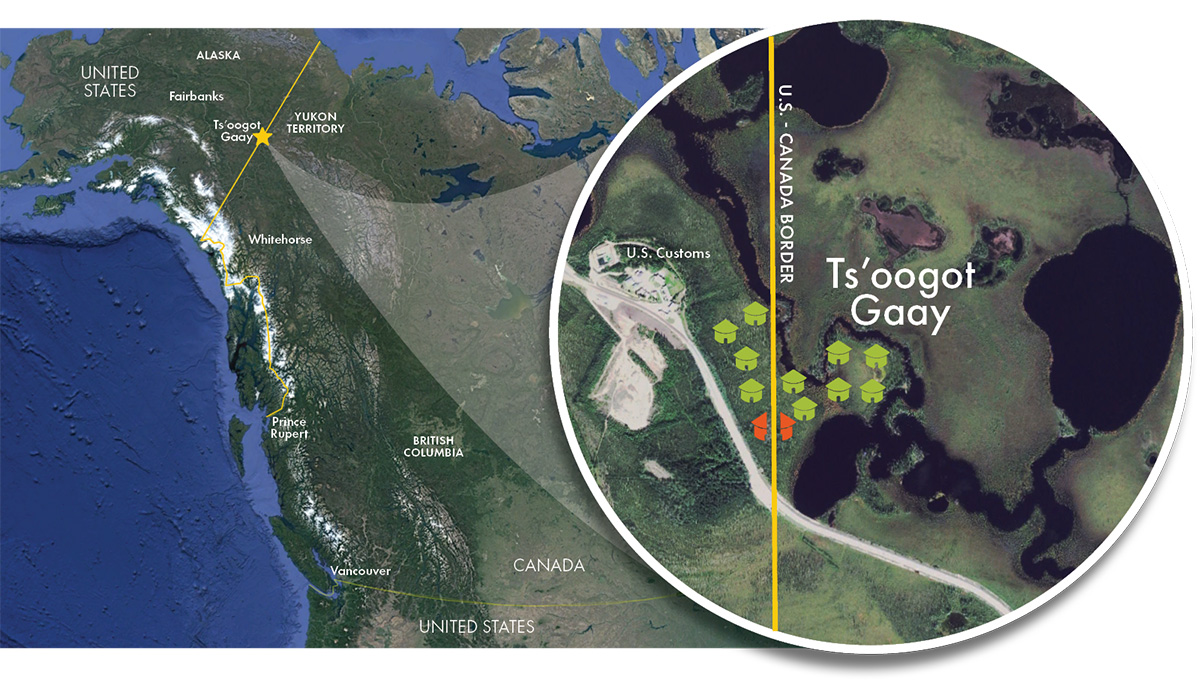

The sound of the saws had been drawing nearer and nearer for days now. Finally, on a mid-summer’s afternoon in 1910, the trees at the edge of the village started falling. Fourteen gritty men, half of them British, the rest American, emerged from the forest on a new trail that measured 20 feet abreast and travelled straight as an arrow as far as the eye could see. The Alaska-Yukon International Boundary Commission Survey, now in its fourth year, had just encountered an unexpected roadblock — the village of Ts’oogot Gaay.

William Raeburn, the head of the boundary field crew, told the inhabitants of the village — a people now known as the Scottie Creek band of the Upper Tanana Dineh — to pick a side of the thin line running through an endless expanse of black spruce.

The house of one man, T’saiy Süül, was directly on what the villagers had just learned was the 141st meridian. If he didn’t move the bark-covered, dome-shaped structure, the boundary team would reduce it to a pile of sawdust.

The authority of the nation-state — the United States on one side of the line, Canada on the other — had arrived in Scottie Creek for the first time.

The Indigenous population of the Upper Tanana region was one of the last on the continent to live outside the realm of the white man. One of the first recorded mentions of them comes from the personal memoir of Alfred Brooks, a member of the 1898 U.S. geological survey in the area:

“I found such men living on the upper Tanana who, except for their firearms, exhibited but little evidence of intercourse with the whites. Most of the men and some of the women were dressed entirely in buckskin, and their bedding was made of furs. Here I saw an Indian hunting with bow and arrow. His arrows were tipped with copper from the gravels of near-by streams. On this same stream, the Kletsandek, a tributary of the upper White River, I found a party of natives searching for the native copper pebbles in the gravels, their digging implements being caribou horns.”

Even the gold rushes of the late 19th century, which brought disease, displacement and exploitation to many Dineh (also known as Dene) in the Yukon, largely bypassed the area. One lost prospector, however, decided to remain with his hosts in the Scottie Creek Valley. His name was William Rupe, and he was still there in 1910 when the boundary commission came through.

Rupe had taught some English to two village ha’skeh — respected, generous men with proven decision-making capacity — and he joined them in their negotiations with the boundary commission. The two Dineh, T’saiy Süül and his brother-in-law, Chajäktà, made it clear that they would not be moving their village, nor would they stop visiting their hunting and fishing grounds on either side.

For several days, the surveyors, resolute in their demands, waited. Finally, Raeburn relented. A document was drawn up, guaranteeing the villagers their rights to both sides of the line. One copy, signed by Raeburn, was kept by Rupe in a red book he used to record important events. The surveyors were allowed to pass through the village, resuming their handy work on the other side, while the Upper Tanana went back to living just as they had before.

Nations divided

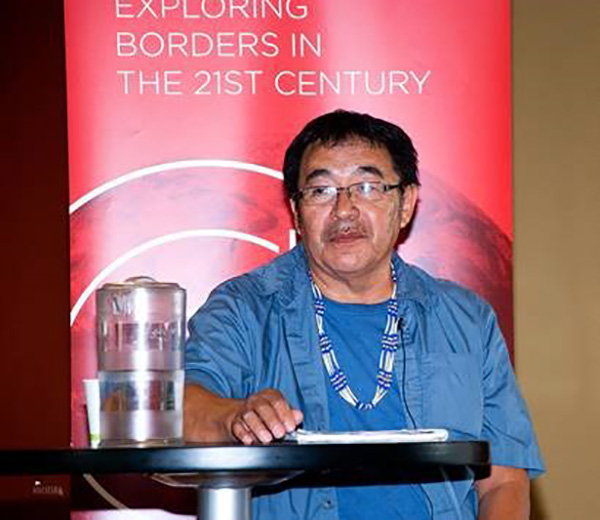

“That paper never made it back to Washington," says David Johnny, an Upper Tanana man whose father was in the village that day. David lives in Beaver Creek, Yukon, the westernmost community in Canada and closest modern-day settlement to the site of Ts’oogot Gaay. The Upper Tanana’s negotiated right to both sides of the boundary was never respected. The Scottie Creek band was divided into two communities, one on the American side, the other in Canada. The United States allows Indigenous Canadian citizens to freely enter, live and work in that country, but Canada doesn’t provide reciprocal rights. This means Indigenous people with Canadian citizenship have the right to reside in their entire traditional territory in either country, whereas those with American citizenship do not.

“Cross-border mobility is much greater for Canadian-Indigenous folks than it is for U.S.-Indigenous folks,” explains Greg Boos, an American immigration lawyer and cross-border law expert. “Canada doesn’t provide much for U.S.-Indigenous folks.”

This problem certainly isn’t unique to Beaver Creek. From Yukon to New Brunswick, dozens of First Nations are divided by the border. In B.C. alone, at least 10 cultural groups have territories or populations on both sides. Blackfoot Territory, now reduced to a few reserves, once stretched from Edmonton, Alberta, to southern Montana. Further east, the Mohawks of Akwesasne even have an international reserve, divided between Ontario, Quebec and New York.

The United States and Britain knew the nascent boundary they created bisected dozens of First Nations, officially addressing the matter in the 1795 Jay Treaty, which states:

“It is agreed that at all Times be free to... the Indians dwelling on either side of said Boundary Line freely to pass and re-pass by Land, or Inland Navigation, into the respective Territories and Countries of the Two Parties on the Continent of America... and to navigate all the Lakes, Rivers and waters thereof, and freely to carry on trade and commerce with each other.”

In the United States, this part of the treaty is in effect. American Indians born in Canada, as the law refers to them, cannot be denied entry to the U.S. for any reason, nor can they be deported. They aren’t required to officially immigrate to the country and are even eligible for social benefits. “Under the Jay Treaty, right now I could load up my truck and go over to Tok, Alaska, and go to the food stamp office and say, ‘I’m here under the Jay Treaty,’ and they’ll give me food stamps the day I arrive in the country,” says David. The only requirement is that the individual prove — with a letter from their First Nation and sometimes a family tree — that they are at least 50 per cent Indigenous by blood. It’s the last racial biometric in U.S. immigration law, though, according to Boos, the level of scrutiny often depends on how “Indian” one looks. “They have the broadest set of rights of anyone in the U.S. apart from citizens,” he says.

Canada, on the other hand, never ratified these Jay Treaty rights, rendering them unenforceable. This means that Upper Tanana with U.S. citizenship can be denied entry to Canada for a variety of reasons, and are also barred from hunting in their territories east of the line. Most of those denied entry have minor criminal charges from their youth, often for drinking and driving. It doesn’t matter if the charge is 30 years old and the person is now a respected elder, says David.

“They just look at that piece of paper and they get horse blinds on themselves,” he says. “They should take into consideration, you know, 30 years you never got in trouble. We weren’t all angels when we were growing up.” Unfortunately, there is little recourse available. Pardons are much harder to obtain in the United States, and while it is possible to apply for a waiver through the Canadian government, it’s not easy. “It takes at least a year and a properly prepared petition that usually requires the help of an attorney. It’s certainly not cheap, probably costing a couple thousand dollars at least,” says Boos. In a community that relies heavily on game meat for subsistence, the cost is simply prohibitive.

Though they still make use of their bush camps, the Upper Tanana Dineh largely reside in two communities: Northway, Alaska, and Beaver Creek, Yukon, which are about 100 kilometres and a couple of customs posts apart. Most have citizenship of the country they were born in; David has a Canadian passport. Ts’oogot Gaay is now empty, some of it reclaimed by nature, some of it buried under a U.S. Border Inspection Facility. It’s more commonly known as Little Scottie Creek these days, and still serves as an important fishing site for local Dineh.

David’s relatives, his grandchildren, his friends are divided by an arbitrary frontier that was determined long before even the United States or Canada had any stake in the area. Almost 90 years before the border survey, the Russian and British Empires selected the 141st meridian as the boundary between their respective northern territories, with little idea of the area’s geography or cultures.

“It wasn’t by our doing that the boundary line came in and the laws that apply to it,” says David, who has now been campaigning for decades for the Upper Tanana’s unrestricted access to their traditional territory, first as chief of Beaver Creek’s White River First Nation, and now as a community leader. He usually feels as though what he says falls on deaf ears, but now something might actually be happening.

Years of activism by David and other Indigenous groups finally caught the government’s attention. As part of a renewed commitment to reconciliation, the Canadian Senate commissioned a report on Indigenous border crossing. After consultations with approximately 100 First Nations across the country, the Report on First Nation Border Crossing Issues was submitted to the government Aug. 29, 2017.

The report makes several key recommendations that David approves of, including relaxing entry restrictions for Native Americans with criminal records, reviewing import restrictions on traditional goods and medicines, and the ratification of the Jay Treaty by Canada, or at least permitting members of federally-recognized U.S. tribes to freely enter and remain in Canada.

Taken

Raeburn’s promise seemed to hold at first. T’saiy Süül’s house was left untouched, a dot of human life in the middle of a 1,200-kilometre line from the Arctic Ocean to the northwest corner of British Columbia. Chajäktà, now in possession of his former business partner’s red book, still hunted on both sides with his son, Andy Frank. William Rupe had left Ts’oogot Gaay roughly two years after the survey, taking his now 10-year-old daughter to Dawson. The half-Upper Tanana girl was enrolled at St. Mary’s, a Catholic school run by the Sisters of St. Ann. She was never seen by her Dineh family again.

In 1919, influenza swept through the village. Five men walked away alive, among them Andy Frank and T’saiy Süül’s son-in-law, White River Johnny. The men started families and continued to live at various camps in the area, connected through an ancient trail network — the closest thing there was to a highway at the time.

Once the Second World War was underway, however, the United States wanted a road to the Territory of Alaska. In 1942, the Alaska Highway came through, intersecting the border exactly at Ts’oogot Gaay. Life changed rapidly for the Upper Tanana. There was now traffic; customs posts were established in Beaver Creek and Tok, Alaska, creating a 180-kilometre "no man’s land" in the heart of Upper Tanana territory.

Sandwiched between two countries they didn’t agree to be a part of, the inhabitants of Ts’oogot Gaay tried to continue as they always had, but a process was already in motion that they couldn’t stop. Upper Tanana people started leaving the bush, some voluntarily, others not.

In 1943, the U.S. army took Joseph, one of White River Johnny’s sons, to Washington state to treat tuberculosis of the skin. After recovering, he was adopted out to a white couple in Alaska; his family was never told, and assumed he had died. The RCMP started visiting the area, taking children to residential school. Every year, David, White River Johnny’s youngest son, watched the RCMP snatch his siblings one by one. When David was six or seven (he isn’t sure which), it was his turn to go. It didn’t matter that he lived in Alaska at the time. The RCMP made an incursion into a foreign country and took young David back with them.

Blocked

The line has shaped David’s life, and recently, his fight once again got a lot more personal. His sister Marilyn can no longer travel with him across the border to visit family and friends or attend community events. She’s terminally ill and confined to a care facility in Whitehorse.

“We want to talk about special considerations for people that have criminal records so they can come back and forth, like when we have potlatches or they want to come visit terminally sick people,” says David. Some of Marilyn’s friends and relatives are among those Canada won’t let in. She likely won’t see them again before she passes.

David may not think of himself as a diplomat, but, in many ways, he is. Although he’s in his sixties now, it doesn’t show. He still has a thick, black head of hair and a surprisingly warm smile for a man on a decades-long quest for justice. But David’s role in the community goes much deeper than the border. These days, he devotes much of his time to passing Dineh culture on to the next generation.

“Just keep them connected to their homeland, to their place,” David says. He now spends a lot of time in the bush, often bringing kids and youth from the community along for a drive, stopping in different areas to look around, occasionally doing some gathering.

David is starting to acquire ha’skeh status, just like T’saiy Süül, who refused to move his house off the border over a century ago. Ha’skeh aren’t just leaders, but also guardians of knowledge and resources, which they have a duty to share with others. But, once again, the border gets in the way. The Upper Tanana no longer hold potlatches — culturally and economically significant gatherings to celebrate births, deaths, or an abundance of food — in Canada due to the heavy-handedness of border agents.

The last potlatch organized in Beaver Creek was for the funeral of a respected elder, Mary Eikland, back in 1981. Naturally, all her friends and kin, many from Alaska, were invited to attend. They didn’t make it past Canadian customs, where all their potlatch gifts and goods were seized as “illegal importations.” Some elderly Upper Tanana never tried to cross into Canada again.

The United States doesn’t have the same restrictions on traditional Indigenous goods, so now all potlatches and funerals in the Upper Tanana community — even for Canadian citizens, whose bodies are brought across the border — are held in Alaska. “If somebody died in Beaver Creek, we usually have our memorial church service in Beaver Creek, but then we’ll go over to the Alaska side to have church and a potlatch over there,” says David. “That way you cover all the bases without really involving customs.”

‘No man’s land’

The RCMP took David all the way to a residential school in Lower Post, B.C. He didn’t speak much English at the time, but that would soon change. “To go all that way to get a half-dozen kids, when you think about that investment of time and energy, boy oh boy, that’s a pretty driven policy,” says Norman Easton, an anthropologist who has studied the Upper Tanana for nearly 30 years, over time becoming a close friend of David’s.

The children could return to their parents in the summer, but only if their family paid their way. White River Johnny didn’t have enough money for the bus fare, not every year and not for every kid. Those able to go back were always then picked up — for no charge — by the RCMP at the end of summer, on behalf of the Canadian government. “We will snatch them for free,” says Easton, who is now working to chronicle the residential school years of the Johnny children. “You want them back? You’ll have to pay the bus fare.”

It was problematic, though, that the RCMP had to keep leaving their jurisdiction to snatch the children. White River Johnny was threatened with prison if he didn’t move to one of his camps on the Canadian side. He complied.

David finished school in the early ‘70s. Finally, he could return to the bush for good and live off the land, just like his father and older brother Joseph, who had found his way back to the family. An uncle had recognized Joseph on a street in Anchorage. He had finished high school and was preparing to enter university, studying marine biology. His uncle gave him some money for the bus to Border City, a roadside shop just west of the border. “Holy shit! I thought you were dead!” said his sister when she saw him get off the bus. She had just crossed over from their camp to buy some supplies and decided to wait and see who was on the bus. Joseph walked with her back into the bush and never looked back.

Joseph spent years relearning “all the Indian stuff,” and would later be known as the last “bush Indian.” Things worked out differently for David. “I wanted to go back to the bush because it’s kind of a quieter life,” he explains. “My dad said, ‘You can’t live like this.’ He was talking Indian to me. ‘You have to live that white man way. You can’t make a living like this anymore. It’s dying, all this stuff that we do. It’s not going to be here anymore.’”

The United States moved its customs post up to the border — right at Ts’oogot Gaay — in 1971, shrinking the "no man’s land" to just 30 kilometres on the Canadian side. Freedom of movement across the border was over. David found himself back in a classroom, getting certified in heavy equipment. He later worked as a firefighter and a teacher in Alaska before returning to Beaver Creek in 1983 and starting a career with the highways department.

It was in Beaver Creek that David became a defender of his people, reestablishing White River First Nation and leading its land claim negotiations with the government. Offered title over a mere 460 square kilometres of their territory and a large sum of money, David walked away from the table March 5, 2005. The First Nation remains one of three in the territory not party to the Yukon Umbrella Final Agreement.

“They retain those rights. It’s a very strong position of power,” says Easton, explaining that they could sign a deal tomorrow and receive $35 million, which would be great in the short term, but not worth it in the long run. ‘I can’t eat money. We need land,’ repeated David and others during the negotiations, highlighting their desire for self-sufficiency. “We don’t want to be tied to the government to look for money every year,” he says. “I wanted to keep my aboriginal rights, title, and interest on the land and resource sharing in all my traditional territory.”

‘Welcome home’

The federal government finally responded to the Report on First Nation Border Crossing Issues on Dec. 12, 2018, announcing it will enhance training on Indigenous cultures for border agents, recruit more Indigenous border services officers and increase co-operation with First Nations in border areas.

“It’s not fair that you have communities whose traditional territories are on either side of the border,” says Marc Wills, an advisor with Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada and contributor to the report. “A border that has been imposed, in their view, upon them, and so that relatives... who are on the other side of the border and want to come and live in Canada have to go through the immigration process.”

The announcement doesn’t address these concerns or include any provisions on relaxing entry restrictions for Indigenous people with U.S. citizenship. However, the government is committing to discussing “potential solutions to a number of more complex border-crossing challenges” with concerned First Nations.

One of these challenges is the locations of the ports of entry at Beaver Creek and Akwesasne First Nation. As with the Upper Tanana, the Mohawks of Akwesasne have territory — the entirety of Cornwall Island in the Saint Lawrence River — between U.S. and Canadian customs posts. “We essentially live in a jail society,” says Akwesasne court administrator Gilbert Terrance. “If we want to go to the north we have to go through the jail guards who happen to be the border customs of Canada. If we want to go south we have to go through the U.S. guards.”

Cornwall residents must go through customs each time they leave the island. If they are returning from the United States, however, they have to drive all the way across the island — without stopping — to Canadian customs on the north shore of the Saint Lawrence. Only then can they turn around and drive back to their homes on the island.

“You can’t stop and pick up grandma. If you need to go to the bathroom, you can’t do it. If someone forgot their medication and had to turn around, you can’t do it. If you get a call and your kid is sick at school so you have to turn around, all of that is susceptible to a $1,000 penalty from the Canadian border agency,” says Terrance. “So what do you do? Do you pick up grandma or pay $1,000? Do you pay $1,000 or do you pick up your kids?”

It’s not only the location of customs that has been contentious, but also the behaviour of Canadian customs agents. Perhaps surprisingly, especially in the Trump era, First Nations consistently report better treatment when entering the United States than when returning to Canada. “The Americans laugh with us. They treat you like you’re American and say, ‘Welcome home,’” says David. “But when we come back to our own community, they look at us and ask, ‘Where do you live?’ even though they’ve known us for the past three years. Like, who the hell are you?”

Even if the government does introduce legislation to address the “more complex border-crossing challenges,” Wills says it won’t be exactly reciprocal of U.S. law. “We do have to tailor it to the Canadian context," he says, pointing out, for example, that Canada likely wouldn’t include a blood quantum provision to determine Indigenous ancestry.

It’s too little, too late for David’s sister, Marilyn. David himself is also cautious. He’s known too many broken promises, reaching back all the way to 1910. It remains unclear whether Raeburn actually had the authority to guarantee to David’s kin in Ts’oogot Gaay that they would keep the right to access all of their land. None of the International Boundary Commission documents or reports mention the region’s Dineh inhabitants, despite numerous interactions with them recorded in the personal memoirs of the men who surveyed the border.

Chajäktà seemed to have a sense of what was coming. “Don’t you forget that man’s name, the borderline chief, Raeburn,” he would tell his son, Andy Frank. “You don’t forget because one day it will be important.” As he was dying, Chajäktà gave his son the red book to safeguard.

In 1957, someone broke into Andy Frank’s hunting cache, 10 kilometres into Alaska, making off with his guns, ammunition, trap lines and the old red book — the Dineh’s only record of Raeburn’s promise.

Just as Chajäktà feared, the line slowly pulled the community apart, taking David in one direction, his brother Joseph in the other. Though they fought to maintain their way of life as long as they could, by the time the authorities allowed David to return home, it was too late.

Regardless of what the future holds, the freedom the Dineh knew for thousands of years is in the past. Even if things do change, that thin line through the trees is here to stay. “This arbitrariness deeply affected the course of their lives,” says Easton. “Given their experience, I couldn’t understand why they didn’t just kill us in our sleep. They judge people on their merit.” ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice, Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: