In 1938, 12-year-old Lilly barely escaped Nazi Germany, and came to Canada with her parents and sister. She eventually married, raised two children, and generally had a healthy, happy life. But suddenly in 2012, aged 86, Lilly found herself in the clenches of serious depression. It was so bad that she contemplated ending her life. With her survival at risk for the second time, she faced an agonizing choice: let the depression consume her or opt for electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), a controversial treatment that involves electric-shocking the brain to induce a seizure.

Most of us associate ECT with the torture endured by Randle McMurphy in One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, and think it’s gone the way of the dodo. Yet ECT didn’t go extinct and its popularity has increased over the past decade, as a treatment for mood disorders like clinical depression and bipolar disorder, and even seniors with dementia and Alzheimer’s, and children with autism as young as eight. In B.C. forced psychiatric detainment has doubled over the past decade, and ECT rates have spiked 36 per cent since 2011. This controversial treatment can even be forced upon non-consenting citizens, according to the BC Mental Health Act, a policy currently being challenged in the BC Supreme Court, by the Council of Canadians with Disabilities, which initially filed the suit with two plaintiffs, including a 66-year-old former nurse who was involuntarily detained and forced to undergo ECT hundreds of times.

The Council had no data on the use of involuntary ECT use in B.C., so I recently applied for that data, via a Freedom of Information request. That data revealed that 280 citizens were forced to have ECT last year, up from 254 in 2007, the earliest year of the available data. Last year, 39 of these people were over the age of 75, including 31 women.

Despite decades of controversy, and conflicting medical and scientific data about its benefits and risks, ECT remains a popular treatment option worldwide among psychiatrists, particularly for women, and increasingly for elderly women like Lilly.

Aging is a big test of our resilience. But Lilly had bounced back from the deaths of her husband and her sister and the various indignities that come with getting older. Living alone in her Kerrisdale home, she increasingly ruminated over the trauma of her early life. In 2000 she was hospitalized at Vancouver General Hospital (VGH) with shingles and became depressed. During that hospital stay, she met Dr. Caroline Gosselin, a geriatric psychiatrist affiliated with UBC and VGH who had been an ECT practitioner for approximately 30 years. Gosselin prescribed Lilly an anti-depressant and did a brief stint of talk therapy. The depression lifted, though Lilly continued taking medication. In early 2012, she was hospitalized again for back pain and was given a nerve block procedure. Afterwards, she made the stressful move to an assisted-living complex near her daughter’s family home. She became depressed again, but this time, it hit her like a truck. That’s when Dr. Gosselin re-entered Lilly’s life.

“She was kind enough to come here to see me,” says Lilly as the three of us sit in the living area of her tidy, tastefully decorated studio apartment in a residential facility for seniors. Dr. Gosselin scribbles on a notepad in her lap as Lilly details the tangle with depression and anxiety that had left her exhausted and hopeless, subsisting primarily on ginger ale. “Dr. Gosselin literally took me by the hand and took me to VGH,” recounts Lilly. “I was put on medications. Several psychiatrists interviewed me. I was then exposed to ECT.”

While an inpatient, Lilly consented to have ECT 12 times, twice weekly during a six-week period. A series of 12 treatments is actually the typical practice with ECT, called an “index course.” At VGH’s surgical suite, the patient is rendered unconscious with anesthetic so that she’s not awake when the electricity causes a seizure. Since a seizure can also cause injury or death, she’s hooked up to an artificial respirator and heart monitor, and also paralyzed by muscle relaxants, and fitted with a bite block, both of which helps prevent bones and teeth from breaking during the seizure convulsions. The skull is fitted with an EEG monitor, treated with a conductivity gel that also prevents skin burns, then the doctor places two electrically charged paddles that look like espresso tamps on either side of the skull, above the temporal or frontal lobes. The press of a button typically delivers 500 to 1,000 millicoulombs of electricity — about 1,000 volts, a few hundred volts fewer than with a Taser. The specific voltage that passes into the brain will vary from one person to the next because human skulls can vary in thickness. That resistance impacts the voltage level; some studies have found that women tend to have thicker skulls, and elderly patients have less brain volume, which increases the effect of the electricity. The electricity penetrates 45 to 100 per cent of the brain and ultimately induces a seizure that lasts anywhere from 20 seconds to 180 seconds, though the goal is to have the briefest possible seizure duration to limit the negative side effects.

ECT practitioners — primarily psychiatrists — don’t know how or why invoking a seizure in an otherwise healthy brain diminishes mental illnesses. About 70 per cent of individuals are said to benefit initially, meaning it curbs their mental illness, but the significant majority typically relapse within six months to a year, and some go on to receive “maintenance ECT” every week, for months or even years after their initial exposure. The rationale for ECT is that it resets the brain’s neurochemistry and neurocircuitry and proponents are quick to underline that ECT has evolved over the decades and, they claim it's safer, reducing its negative side effects to virtually nil. This viewpoint contrasts with many patient accounts, and a growing body of scientific evidence that ECT is ineffective and routinely causes a wide range of cognitive impairments including persistent memory loss and other neurological signs of brain trauma.

Critics — psychiatrists, psychologists, neurologists, neuroscientists, consumer advocacy groups and ECT patients and their loved ones — believe that ECT is ineffective and dangerous, should never be forced on non-consenting citizens and people who can’t consent, such as children and elderly people with dementia. Some critics equate ECT with barbaric torture and think it should even be banned.

Public opposition to ECT helped instigate a U.S. FDA hearing in 2011 that resulted in calls for restricting access and for comprehensive safety testing on ECT machines. Eighty per cent of the 3,045 FDA testimonies expressed opposition to ECT, ranging from ECT patients to medical specialists. The FDA hearing highlighted the fact that adequate safety and efficacy testing had never been conducted in the U.S. and Canada, because the machines developed in the 1930s were grandfathered onto approval lists after regulatory organizations formed. In some regions, public opposition to ECT has impacted political legislations. In places like Texas and Scotland, usage data is now collected and made public and includes patient demographics. This data, and other studies have consistently shown that the majority of ECT recipients are women, that an increasing number are elderly like Lilly and that in countries such as the U.K., New Zealand and Australia, up to 60 per cent of patients are forced to have ECT involuntarily.

Here in Canada, the picture is much murkier since we have no national or regional public database tracking demographics, including involuntary ECT. In Canada we know that approximately 75,000 ECT treatments are done yearly, based on a recent poll conducted by Gosselin and a group of ECT practitioners who have since called for a national accreditation program and underlined flaws in the system, including a lack of standardized training protocols for practitioners and nurses. Even so, some institutions still use dangerous, old sine wave machines. In contrast to newer so-called “brief pulse” machines, sine waves provide a constant flow of electricity to the brain, have no modern safety features and cause increased damage to the brain. Despite these concerns, Canadian ECT practitioners also hope to increase access to ECT, claiming that it’s the only fast-acting therapy for acute cases of mental illness, particularly suicidality.

According to B.C. government billing records, in the past decade approximately 10,000 ECT treatments were done yearly at B.C.’s hospitals and affiliated outpatient clinics, though the number of procedures has increased from 9,596 in 2011/2012 to 13,093 in 2016/2017. B.C.’s ECT numbers are higher than in Quebec (with 11,045 procedures last year in a province with twice as many citizens), more than three times more than Scotland (3,799 in 2016) and only four thousand shy of the 17,006 procedures done in Texas in 2016 — in a population of almost 28 million people. Fourteen of those Texas citizens given ECT were treated involuntarily, compared to 280 in B.C.

Pigs in a poke

The story of ECT’s checkered past began at a time when nature began to trump nurture as the rationale for mental illnesses. By the late 1800s, psychiatrists and neurologists were eager to establish legitimacy with biological theories and therapies for so-called insane and feeble-minded people. Unfortunately, the first half of the 20th century was plagued by junk science in the form of draconian treatments and eugenics theories and programs, which were instrumental in the spread of government-sponsored mental hospitals, forced institutionalization and even sterilization of people with mental illnesses, in the U.S. and Canada.

Italian psychiatrist Ugo Cerletti developed the first ECT device in 1938, after watching slaughterhouse pigs electric-shocked into epilepsy-like paralysis and submission. He claimed to cure schizophrenics, was nominated for the Nobel Prize, and soon his colleagues hit the road promoting ECT round the globe.

By the 1940s, North American mental asylums were crammed to bursting — with traumatized war veterans, schizophrenics, people with organic illnesses, immigrants deemed genetically defective, and other social misfits, including melancholic housewives, gay men and rebellious teenagers. Conditions at insane asylums were worse than at prisons and in a 1946 Life Magazine exposé, even compared to Nazi concentration camps.

To quell political and public pressure, psychiatrists looking for innovative and inexpensive new treatments heralded ECT, along with insulin coma therapy and lobotomy. But behind the asylum walls, these procedures were acknowledged as “brain-damaging therapeutics.” ECT was used primarily for crowd control because it was the cheapest and easiest method for rendering patients manageable. Shock-related brain trauma caused a range of behaviour changes from sudden euphoria and childishness to zombie-like docility and memory loss, which was seen as a key beneficial aspect of the treatment, since memory-incapacitated individuals no longer had the concentration level to stew over poetry, fixate on their psychological traumas — or even remember their former selves.

One of the most vocal proponents of ECT at the time was New York-based psychiatrist Max Fink, now known as the granddaddy of ECT. In the mid-’50s and again a decade later he endorsed ECT because it resulted in “cerebral trauma.” In a 1974 textbook he stated that “patients become more compliant and acquiescent with treatment.”

In that era, many notable people had ECT, including musician Lou Reed (ostensibly to cure his homosexuality), poet Sylvia Plath and novelist Ernest Hemingway, who died by suicide mere months after ECT. In that era, as many as one in 200 ECT recipients died from ECT, while others suffered heart attacks, strokes, vision problems, epilepsy and cognitive issues — most especially the wholesale loss of years to decades of memories — college educations, career skills, marriages, births and deaths of loved ones. Many were so debilitated that they needed life-long care.

By 1960, modified ECT was standard in Western countries, involving anesthetics, artificial respiration and muscle relaxants. Many patients no longer had to be strapped down and endure a waking horror while being shocked, yet while the procedure looked less gruesome, many still suffered cognitive damage, particularly memory loss. By the late 1970s, the public outcry against ECT coincided with the development of powerful new psychiatric drugs and ECT became less popular, or at least fell off the public radar.

ECT specialists developed new methods to decrease its dangerous side effects and promoters like Fink began denying that ECT causes brain trauma. Fink founded an ECT journal and teamed up with another psychiatrist named Richard Abrams to write papers on ECT’s efficacy and safety. Abrams rarely acknowledged that he co-founded Somatics Inc. , an ECT machine manufacturing company that remains one of the two surviving U.S. ECT manufacturers, providing and servicing all ECT machines in North America.

The take-a-pill 1980s ushered in a new era of pharmacology. Now there’s a proverbial candy store of options, but also increasing evidence of adverse side effects, and the drugs don’t work for at least 30 per cent of people. ECT is touted as an alternative to drugs, though the significant majority of ECT recipients also take pharmaceuticals.

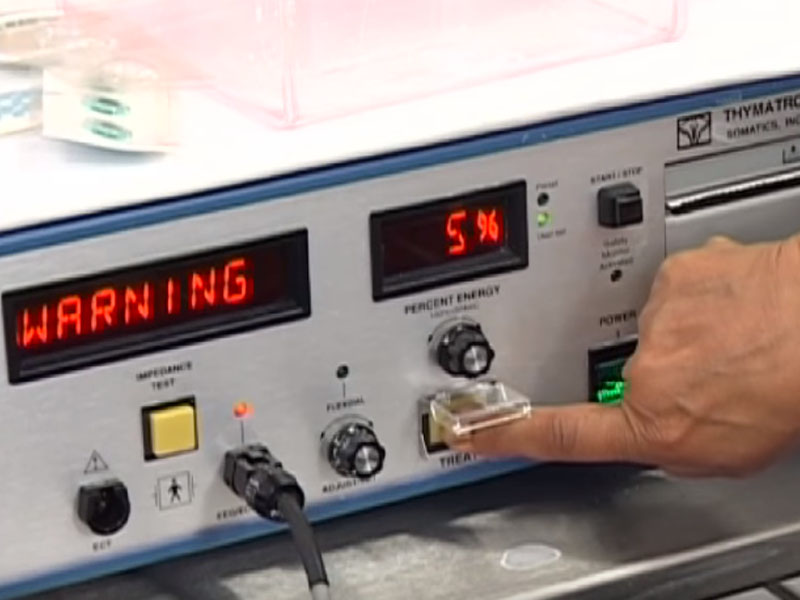

ECT machines have evolved to deliver what proponents say is a safer method of shocking the brain, such as machines that provide brief pulses of electricity instead of the constant electricity of the sine wave machines, providing computerized settings so that electrical dosages can be customized for each patient, and adding EEGs monitors that record seizure activity in the brain and spit out the recording like a grocery store receipt.

Back to the future

In Royal Columbian’s spa-like outpatient surgical suite, a block away from the hospital proper, Dr. Jenny Rogers shows me an EEG reading from a a patient she treated with ECT prior to our interview this Thursday morning.

“This is a very nice tracing,” says the geriatric psychiatrist, pointing to the initial small peaks and valleys called the neuron “recruitment phase” and “electrical kindling,” followed promptly by an erratic-looking set of highs and lows — picture the big tell on a lie detector — “that’s an optimal seizure of about 20 seconds,” says Rogers. “Next you see the brain suppressing the seizure. That’s what you want to see.”

The left hand side of the strip provides the dosing level, in this case, 576 millicoulombes of electricity, the peak amount of electricity that this specific MECTA brand ECT machine can transmit. (Other ECT models can deliver up to 1,200 mC.) “This person has been on ECT maintenance for a long time, which means you have to raise the [electrical] dose to achieve the seizure,” says Rogers.

One of the many marvels of the human brain it that it has natural protective mechanisms to prevent and override seizures. To cause a seizure, electric shock dosage has to be two to six times higher than the brain’s seizure threshold, and over time, with increased ECT exposure, the brain responds to the electric shock by increasing its seizure threshold, which tends to be much lower at the first ECT procedure, requiring lower voltage. The goal should always be to elicit a seizure using the least amount of electricity possible to prevent unnecessary cognitive issues, but seizure thresholds differ widely from one person to the next; women and elderly people typically having much lower thresholds, meaning that a much lower dose of electricity will induce a seizure — and cause increased cognitive issues for women and elderly people.

Maintenance ECT as it’s known, is another controversial subject. Rogers tells me that the recently treated man in question initially benefited from ECT. “But [post-ECT] I think something happened, he started to feel a bit worse, was agitated, so now we’re doing it weekly,” she says. “He’s so calm and relaxed and happy afterwards. That’s a very good result, but most people are in a grey zone and many do need maintenance ECT to some degree,” she says. “ECT doesn’t work if you’re not having it. The longer patients are away from ECT, the more likely they’ll relapse.”

About half of Rogers’ ECT patients are elderly, but she says there have been “more young people” having ECT, particularly for suicidality. “Some patients say to me, ‘I don’t care what you do, I don’t really want to wake up.’ That’s one of the reasons they signed up for ECT, they’re so suicidal and nihilistic that they say, ‘I hope I don’t wake up from it.’”

Her geriatric patients are typically depressed. “They seem to tolerate the ECT pretty well and it’s been helpful to have a non-pharmaceutical option,” she says. “Depression is a very bad problem in geriatric adults. It’s a time of a lot of changes, at a time when you feel vulnerable. ECT is a way to get them better so that they participate more in life.”

Rogers, who now works in the geriatric clinic at Peace Arch Hospital, and is a clinical instructor at UBC’s Faculty of Medicine, contends that the only truly risky aspect of ECT is the use of the anesthetic, and she informs her patients the oft-cited mortality rate of one in 10,000 for any surgical procedure, an estimated used by the American Psychiatric Association’s ECT guidelines. Scientific research on ECT mortality rates points to much higher mortality rates. A comprehensive 2010 review analyzing numerous individual studies that tracked ECT-related deaths, found mortality rates ranging from a 10 to 100-fold higher risk of death than the APA number, including one study with a conservative estimated death rate of as many as one in 91 ECT recipients who died in the midst of an ECT course (not by later deaths due to ECT complications, or suicide which is often dismissed as related to the mental illness, not the ECT). Other research on adverse effects found that an estimated seven per cent of healthy individuals and more than half of people with pre-existing conditions will experience ECT-related cardiovascular complications because it causes the blood pressure to dip during ECT and then jump back up afterwards.

Regarding risks to cognitive function, Gosselin warns her patients that side effects like confusion and transient memory loss are common for at least a month post-ECT, but 90 per cent of ECT procedures in Canada are done to outpatients given ECT two or three times per week, spaced one to three days apart. That makes it difficult to judge patient capacity for true informed consent because a patient will have completed 12 ECT treatments before the confusion and memory problems ideally resolve. Patients also face other medical risks post-ECT, which are impossible to monitor among outpatients, including the risk of life-threatening persistent seizures, called status epilepticus, which can happen after as much as 19 per cent of procedures. These prolonged seizures are known to cause more extensive destruction of brain cells and have an overall 19 per cent mortality rate, but they’re very difficult to detect because they can occur without convulsions. This very serious risk is most common during an individual’s first exposure to ECT. According to a 2007 paper by a Scottish ECT specialist, it’s sometimes “impossible” even for trained medical practitioners to determine seizure end-points, even with the most sophisticated ECT machines providing computerized EEG readings, which fail to provide reliable seizure end-point readings 28 per cent of the time.

Rogers, who has performed ECT procedures for more than a decade, tells patients to expect some confusion for only 24 hours after ECT, and she says that’s related primarily to the anesthetic, not to ECT. She says she’s never had a patient suffer persistent cognitive dysfunction and has heard only one case of that among ECT practitioners, around a U.S. lawsuit in the 1990s.

Numerous historic and recent published clinical studies have indeed documented substantive and persistent or permanent memory loss, ranging from 38 per cent to 79 per cent of patients. A wide range of long-term cognitive deficits were even called “routine” in a 2007 study by longtime ECT proponent Harold Sackheim, who found that all ECT recipients had negative post-ECT effects, that 82 per cent of women had persistent memory deficits, and that the elderly were particularly vulnerable. Another comprehensive review published in Frontiers in Psychiatry, analyzed all published ECT-related brain studies, dating from as early as the 1930s, until 2013. From the earliest EEG data to the most recent brain scans, the researchers found proof that ECT causes significant and extensive brain trauma, from the frontal lobes to the deep brain structures including the hypothalamus and the hippocampus. The authors concluded that ECT “affects the brain in a similar manner as severe stress or brain trauma” and that any perceived depression improvement “appear consistent with those typically seen after severe stress-exposure and/or brain trauma.”

In other words, ECT is effective because it causes brain damage.

Other recent brain studies have also documented ECT-related pathological changes, including “substantial elevations” in four of 10 ECT patients’ levels of S-100b, a marker that has been well-established as an indicator of cell damage and dysfunction of the blood-brain barrier leading to brain damage, and long-term disability after head injury, factors that neurology specialists connected to ECT decades ago. A PET scan study revealed reduced glucose metabolism in the frontal lobes of ECT patients, a finding also discovered in patients with traumatic brain injury . Scientific studies have also found that traumatic brain injuries cause suicide, many psychiatric disorders and behavioural issues, including aggression, impulsivity, mania and euphoria.

ECT’s life-saving potential has also been questioned, particularly the claim that it curbs suicidality. A 2011 British study that tracked suicide among psychiatric patients found that nearly half of patients treated with ECT died by suicide within three months of discharge, concluding there was a “high risk of suicide” among ECT recipients. A 2005 Swedish study found that ECT recipients were more likely to make “highly lethal” suicide attempts than patients given medications. And a 2007 Danish study of deaths among inpatients at a psychiatric hospital tracked over a 25-year period found that ECT recipients had an increased risk of suicide death (20 per cent of ECT recipients; another four per cent died from “accidents”) compared to other inpatients, and that comparative risk of dying by suicide was “greatly increased” for inpatients, within a week post-ECT. Another 2010 analysis looked at all published studies analyzing ECT’s effectiveness, concluding that “there is no evidence at all that the treatment has any benefit for anyone... or that it prevents suicide,” and that “The continued use of ECT represents a failure to introduce the ideals of evidence-based medicine into psychiatry.”

Dr. Rogers, like many practitioners, contends that ECT is life-saving and the risks are minimal, “probably one in a million.”

‘Memory is like the ocean’*

Forty-six-year-old Julia used to be a successful headhunter of senior banking executives. She considered ECT a last resort to curb a serious depression that had plagued her for six years, after 30 medications and some psychotherapy failed to put a dent in her depression and anxiety. “At that point, you want to try anything, it’s this one lifeline offered to you,” she says over lunch at Milestones. “But I don’t think my psychiatrist warned me about the risks. He called ECT a subtle reboot.”

At the age of 39, Julia was given ECT approximately 50 times during a four-month hospitalization at UBC Hospital’s psych ward. “ECT was terrible, really hard on my body. I had memory problems and couldn’t remember whole conversations an hour later. I couldn’t sleep and was so anxious — it’s really invasive.” Aside from the threat of serious cognitive behavioural issues like euphoria and mania, ECT is known to cause, at the very least, short-term confusion and memory loss. With the three times weekly doses of ECT, Julia had no time to recover from each dose, and it’s no wonder her memories of her hospital stay are foggy at best. Her family lived in Ontario, so she had no loved ones living nearby, to visit, monitor her health and advocate on her behalf. But her close friend Heidi visited her weekly and told me that Julia’s mood initially seemed improved, but her cognitive issues “got substantially worse — she’s an avid reader and likes to knit and quilt, but that took too much concentration,” says Heidi. Suddenly this smart, savvy, once-vibrant, high-achiever was “like a little girl at the bottom of a well.”

After the 50th ECT session, Julia escaped the hospital late one night, fearing she wouldn’t have the guts to say no to the next day’s scheduled ECT session. When her psychiatrist, UBC-based Dr. Andrew Howard, promised that she didn’t have to have more ECT, she returned to the hospital for another month to recover.

Julia says the ECT has caused persistent memory loss. “Most of my childhood memories are gone,” she says. “I’ll talk to my mom and she’ll say, ‘Oh you did this or that,’ but I have no memory of it. I have to trust people when they tell me anything about my past.” She doesn’t remember Heidi’s bachelorette party and wedding in 2008, and Heidi is often shocked when they bump into Julia’s other friends and she has no recollection of them.

“There are big holes in the fabric of my life. That’s stressful and depressing,” says Julia, who has struggled with panic attacks and suicidal thoughts. “I came close a number of times, but I’m conscientious, I didn’t want to hurt or disappoint my family and friends. To this day [my psychiatrist] says, ‘It’s not a big deal, you have some memory loss.’ It’s a lot worse than that. But doctors get really defensive about that. They really believe it works.”

Dr. Gosselin is a long-time defender of ECT, and she hails studies done in 2008 and 2009 that she says provides “physical evidence that ECT is doing exactly the opposite of what we’ve all been scared about all these years”: post-ECT evidence of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) a neuropeptide thought to cause brain cell growth and rejuvenation. “That’s what I tell patients now,” says Gosselin. “We are learning that ECT’s not resulting in brain damage, it’s bringing about brain repair.” Yet other studies have found increased BDNF resulting from exposure to warm, sunny weather and St. John’s Wort. It’s also considered a marker for cellular brain damage, linked to natural neuroprotective factors that kick in after brain trauma in humans, and also rats with nerve damage, rats exposed to fear conditioning to help study memory consolidation, even in rats exposed to cigarette smoke. Researchers have also linked BDNF to significant structural brain changes that might cause autism, and other research has shown that the elderly are particularly vulnerable to ECT-related brain trauma. One 2008 Dutch paper found that half of studies conducted on elderly ECT patients indicated cognitive impairments and the researchers stressed an urgent need for more extensive research with elderly ECT patients.

Gosselin, a geriatric ECT specialist, doesn’t feel the need to wait for more evidence.

“We’re trying to train and teach our medical residents not to look at ECT as a last resort,” says Gosselin, who was awarded a UBC faculty teaching award for career excellence in 2015. “Most patients don’t want or need ECT. But it can bring about a faster response than medications for patients that need to get better immediately. So we immediately go to ECT. Especially if people are so sick their lives are at risk. If you’re 90 per cent better, let’s aim for 100 per cent recovery.”

Hope vs hype

Despite the many documented serious side effects of ECT, B.C.’s Ministry of Health’s ECT guidelines provide very little information about adverse effects, and tends to downplay the various risks as rare, citing the APA’s inaccurate risk of death of 1 in 10,000. The B.C. guidelines, written in 2002, references no scientific studies done after 2001, and it’s peppered with citations from historic ECT promoters like Fink and Abrams. The guidelines state that ECT can be used “at all stages of pregnancy,” on seniors with both dementia and depression, with non-consenting patients, prepubertal children and even people with “mental retardation.” The guidelines also state that post-ECT, “memory may improve.” Its “Patient Information and Informed Consent” pamphlet also includes many unscientific declarations, such as that ECT does not “leave permanent memory loss.” A similar patient document provided at the VGH website also provides no scientific medical resources or studies related to adverse effects, and it also minimizes the potential risk of persistent cognitive issues, boldly asserting that permanent memory loss is a “myth.”

“That’s a blatant lie,” says U.K.-based clinical psychologist Dr. John Read. “There’s overwhelming evidence that ECT causes brain damage, cognitive dysfunction and especially memory loss. Also alarming is the pamphlet’s claim that ‘ECT is often considered the safest method of treatment for pregnant women and the elderly.’ Both have been shown to be particularly susceptible to the brain damage caused by ECT. We also need to be cognizant of the fact that the archetypal ECT recipient remains, as it has for decades, a distressed woman more than 50 years old.”

Read, a professor at the University of East London, has analyzed data from all the published research studies related to ECT’s safety, efficacy and risks, and has published many papers in medical journals. His most recent paper published in 2017, looking at efficacy data since 2009, concluded that, “Given the well-documented high risk of persistent memory dysfunction, the cost-benefit analysis for ECT remains so poor that its use cannot be scientifically, or ethically, justified.”

“Psychiatry has a long history of interpreting the result of brain damage as ‘improvement,’” says Toronto therapist Bonnie Burstow, a professor at the University of Toronto’s Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, and an outspoken critic of ECT. Burstow points out that ECT is big business, and much like the pharmaceutical industry, research, endorsements and usage of the treatment are plagued by financial incentives and conflicts of interest. A 1996 Washington Post investigation documented that a number of prominent ECT proponents receive consulting fees and research money from MECTA or Somatics, the manufacturers of the two most commonly used ECT machines, including psychiatrists Max Fink, Harold Sackeim and Richard Weiner — three of the six American Psychiatric Association ECT Task Force members that shape ECT guidelines and policies, and generated much of the research cited in BC’s Ministry of Health ECT guidelines. Somatics is co-owned by two other vocal ECT proponents, psychiatrists Richard Abrams, and Melton Swartz; the latter commented that ECT service fees allow psychiatrists to "bring their income almost up to the level of the family practitioner.” In B.C., for example, more than $1.1 million was spent on ECT procedures in 2016. The cost of an ECT procedure is approximately $100, and it only takes minutes to perform the ECT procedure.

Forced detainment and forced ECT rates

B.C.’s Mental Health Act doesn’t require the tracking and publication of statistics, demographics and annual reports related to involuntary admissions, and with no regulated accountability measures, it’s difficult to find out the exact number of citizens involuntarily detained. Based on data from an earlier FOI from another citizen, the B.C. government did release data on involuntary hospital discharges. 14,455 citizens were involuntarily discharged in 2015/2016, up from 8,762 in 2005. The number that voluntary discharged was lower at 11,415 in 2015-16 (only a slight increase since 2005), so that more B.C. residents were committed to hospitals involuntarily than chose to be hospitalized. According to that data, in the past decade, overall yearly involuntary hospitalization rates have almost doubled, to 20,008 in 2015-16 (exceeding the voluntary rate of 17,060), including 821 kids aged 15 and under, and 718 seniors aged 76 and older. No data is available on the number of citizens involuntarily admitted to hospitals each year, so the rates could be much higher than those reported above.

The new B.C. lawsuit challenging forced medical treatment was filed in September 2016, taking aim at the B.C. government’s B.C. Mental Health Act, which gives a single doctor unchecked power to hospitalize citizens involuntarily for 48 hours. Not because they are a danger to themselves or others, but simply because a doctor believes they have “a disorder of the mind” requiring “safe and effective psychiatric treatment.” The approval of a second doctor, usually a colleague of the first doctor, allows for another month of detainment. After that, a single doctor can opt to keep a citizen detained for months, or years, just by filling out paperwork.

Once detained, the mental health act includes “deemed consent” capabilities that allow a hospital director, a doctor or even a facility’s nurse to force detained citizens to have specific treatments, including ECT, even if family members or an independent advocate objects.

According to a recent report, “Operating in Darkness,” by Laura Johnson of the Community Legal Assistance Society, “the B.C. Government has been aware that the deemed consent model is not constitutionally compliant for over a quarter of a century and has been repeatedly called on to review and amend the deemed consent model.” Johnson’s report features the testimonies of many B.C. legal representatives who “repeatedly described our mental health detention system as opaque, unclear, and obscure — a system in which people are tucked out of sight with no monitoring, oversight, or accountability.”

Detained citizens are subjected to a wide range of abuses that violate the Canadian Charter of Human Rights, including forced physical and chemical restraint (via powerful drugs), clothing removal, even by private security guards (who now staff “the majority of psychiatric hospitals”), forced solitary confinement, and forced medical treatments, including ECT, which can be approved by a single doctor or designated health provider. Canadian prisoners are provided more rights than B.C. mental health patients, such as restrictions on the length and type of solitary confinement, the right to refuse medical treatments and the right to receive legal aid. Citizens detained via the mental health act are provided no legal aid funding to fight an involuntary detention or a specific treatment; even if they are informed that they have a right to a second opinion, and request it, they can be forced to have any treatment that first doctor prescribes, for months before a second opinion is given. Typically that second doctor is a colleague of the first doctor, and approves the treatment, but if not, the primary doctor is not legally obligated to stop treatment. “The rights violations and procedural unfairness identified throughout this report have flourished in the absence of systemic oversight and evaluation,” writes Johnson. “We have allowed our mental health system to stagnate and operate in darkness. As a result, B.C. is considered the most regressive jurisdiction in Canada for mental health detention and involuntary psychiatric treatment.”

Until I received the FOI data, there were no publicly available statistics about how many B.C. residents were forced to have ECT, like the 66-year-old former nurse initially named as a plaintiff in the B.C. Supreme Court challenge.

Among the more than 20,000 citizens involuntarily detained under the B.C. Mental Health Act, 280 were given ECT in 2016, a decrease compared to 2010, when 319 people were given ECT, but an increase since 2007 (the first year of data provided) when the number was 254. Of the 280 people forced to have ECT in 2016, 170 were women, 35 of these women were aged 66 to 75, and 31 of the women were aged 76 or older. The FOI data doesn’t include a separate category for children and minors, but instead lumps them in among a zero to 40 age category. The data also excludes any information about the number of ECT treatments given to these non-consenting citizens.

B.C.’s regulations around involuntary patients and its ECT practices have received little media attention. The subject of ECT got some attention 2002, when The Province ran a few exposés, after the head of Riverview Hospital claimed ECT was being overused, particularly among the elderly. An investigation conducted by Dr. Gosselin concluded otherwise.

The new NDP government has inherited a mental health system that has consistently been singled out as the most flawed and regressive in Canada. The Supreme Court challenge of the mental health act was lodged against the former Liberal attorney general. Now that David Eby is the attorney general, the plaintiff’s lawyers are talking to his office’s lawyers, and a government spokesperson told The Tyee that government officials cannot provider public comments about an active legal case. It could take many months for the case to proceed through the disclosure phase. In the meantime, I contacted the offices of Eby and Judy Darcy, the Minister of Mental Health and Addictions. A staffer from Darcy’s office said that they were unable to comment on the legal case, or any potential changes to the act, but that they are “reviewing the recommendations” from the Operating in Darkness report.

The voices of ECT recipients

While ECT proponents and critics remain fiercely committed to their own interpretations of the Hippocratic oath — do no harm — the opinions of individuals who receive ECT are even more complex and contradictory.

Throughout her 12 ECT sessions, Lilly says she didn’t suffer adverse effects and gradually “started to feel more grounded. Not 100 per cent, but the depression started to ease. At the end, I felt a lot better and today I feel normal,” she says, acknowledging she’s on a new medication. “Don’t ask me the name; it’s stronger,” she adds. Gosselin quietly interjects, “Not stronger; different.”

“I’m comfortable. This place is home now,” says Lilly, now aged 91. “My son and daughter look after me. I have nothing to worry about. I have purpose in life, which I didn’t have before ECT. Depression is a very debilitating disease. But the will to live is very strong, even when you’re wounded or hungry. It’s an odd thing, but it’s true. The will to live is very strong.”

Julia’s personal life improved significantly three years ago. She met a good man with two children. After many years on long-term disability, she’s now a busy stay-at-home mom, which is challenging given her continued cognitive issues and memory loss. She still juggles “too many” medications and sees a talk therapist, though Julia says her therapist contends that the ECT-related memory loss has made therapy more difficult. “When I look in the mirror, I don’t feel like myself,” she says. When she looks at photos of her former life — the highs of career success, the lows of an estranged relationship with her father and a 10-year marriage to an abusive man during her twenties, and everything else in between — “it’s like looking through gauze. The memories aren’t there. Or they feel so fragile, like they’ll fall apart.” She still has monthly consults with the psychiatrist that prescribed all the ECT. She credits him for talking her off the ledge many times, sometimes by phone, after hours; she has his direct line.

The threat of forced ECT looms large in Julia’s mind. “When I was in the hospital, I was afraid they’d give me ECT against my will,” she says. “You have to be an advocate for yourself when you’re at your absolute lowest state. That’s impossible. Now, when [my psychiatrist] mentions ECT, my heart races. I’m afraid. ECT took something from me. I’m not myself anymore. I’m not a whole person.”

* A quote from the book On the Sea of Memory by Jonathan Cott, a renowned journalist who suffered extensive, permanent memory loss and cognitive deficits after ECT. The full quote is: “Memory is like the ocean because from memory flow all thoughts and words.” ![]()

Read more: Health, Science + Tech

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: