"SAFER? What's that? Should I apply for it?"

Seventy-one-year-old Brenda Berck leans forward in a garden chair outside her Vancouver West End apartment. She hands over a blank application form she received in the mail, hoping for an explanation.

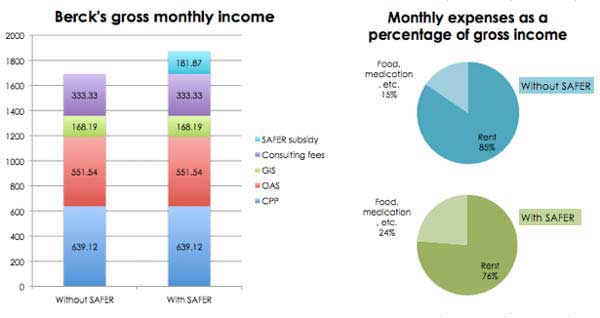

Berck currently receives $1,358 a month from the Canada Pension Plan, Old Age Security and the Guaranteed Income Supplement, and an additional $333 for some consulting work. After paying for rent, she has a mere $262.18 to spend on food, medication, transportation, social activities, clothing and toiletries. Berck moved to the West End in 1985, shortly after she was offered a job at the Vancouver Writer's Festival. Now retired, she is struggling to stay in the $1,430 one-bedroom apartment she's called home for nearly three decades.

Like many B.C. seniors her age, she didn't know that help was right under her nose -- until now, that is.

Shelter Aid for Elderly Renters, or SAFER, is a form of rental assistance for B.C. residents aged 60 and over who spend more than 30 per cent of their gross income on housing. Created by B.C. Housing in 1977, it currently subsidizes more than 17,000 senior households in the private market.

According to Eric Kowalski, executive director at the West End Seniors' Network, where Berck first heard of SAFER, the subsidy helps, and more seniors should know about it. Alone, however, it's no panacea. Stagnating incomes coupled with gradual increases in rent prices are slowly forcing older tenants out of their homes, he said.

"We hear about the high-profile cases a lot, like renovictions, but what we don't hear about is the 'flow squeeze,'" he said. "Seniors are slowly pressured to cut things. First they cut cable, then they cut the phone plan to basic, then they cut food and medication. One more rent increase, and that's it."

Most people don't like to complain, either because they are ashamed, scared or feeling hopeless, Kowalski said. For the most part, it's a quiet crisis.

How it works

Earlier this year, the federal and B.C. governments announced a $12.5-million annual investment that would enhance SAFER. To calculate the subsidy a senior receives, the government measures rent as a percentage of income, but rents are capped at certain levels for singles, couples or groups. In April, the rent ceiling used to calculate benefits for the subsidy increased roughly by nine per cent, allowing more seniors to apply.

It's the first increase since 2006, when B.C. Housing widened eligibility by allowing seniors living trailers to apply for subsidies, doubled the program's budget, and established higher rent ceilings for Metro Vancouver. Since then, the SAFER has helped an additional 5,000 seniors, and average subsidy rates have risen to $160 from $105.

As an over-60 adult making a little over $20,000 a year, Berck would qualify for a $187.81 SAFER subsidy, allowing her to minimize cutbacks on food and other expenses.

But even that would be a short-term solution. Her consulting contract is set to end next year, and without the extra $333, her rent will be more than her income. Even with an adjusted SAFER subsidy, she will struggle to make ends meet. She must find an alternative option, or face eviction.

Berck is hesitant about moving to another neighbourhood. "Choosing where to live has to do with costs and how you can move around, but it also has to do with where your life is. My life is here."

Assisted living is an option, but she's afraid it might undermine her independence even further. "Just because we are seniors doesn't mean we are inept. I don't want people to do my laundry and cook me food. I can do that on my own."

SAFER's calculation takes into account household income and size, rent paid, and where an individual lives. The subsidy is distributed on a sliding scale, with the most money given to those with the least income. However, the program doesn't consider rent rates above $765 for singles and $825 for couples in Metro Vancouver.

B.C. Housing says these rent ceilings reflect average market rents in the region, but figures released by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation tell a different story. According to the CMHC, average rent for a one-bedroom unit in Metro Vancouver was $1,005 in 2013, $240 (nearly 25 per cent) above SAFER's maximum rent level for singles.

'Unrealistic' rent ceiling

Gail Harmer is one of thousands of seniors who benefits from the program. She has received SAFER since 2007, after retiring. "When I stopped working there was a big drop in my income. From one day to the other, it went from $3,500 a month to $1,900 a month."

Today, she receives $65 a month in subsidy. She pays roughly $1,300 in rent and water, leaving a little over $600 to cover her other expenses.

Harmer believes SAFER is flawed in many ways. As a former welfare worker, she said the application process is very cumbersome for seniors who aren't used to the language and have difficulty navigating information online.

"More importantly, even though the subsidy is available to anyone who is eligible and applies, many seniors don't know about it," Harmer said. Berck, for example, has been eligible for the subsidy for at least seven years, but she wasn't aware of it until recently.

Harmer believes that even with the subsidy's help, most seniors still can't afford to stay in Vancouver. "I don't know of anyone that is paying $765 a month for a one-bedroom. The rent ceiling is unrealistic."

In the end, she said, SAFER is a "very poor band-aid solution."

'At this point, every penny counts'

According to a United Way report released last year, Metro Vancouver was home to 312,895 seniors in 2011, up 60 per cent from 2001. That population is expected to increase by 166,071 between 2011 and 2021 and by 193,972 between 2021 and 2031, according to Statistics Canada.

Without proper support and services, many seniors will be in similar or worse situations than Berck and Harmer.

Tyng Wey Fan is an "adult guardianship" worker at the Bloom Group, a non-profit organization that serves vulnerable and marginalized people. The adult guardianship program helps 840 low-income seniors who are no longer able to manage their finances or live completely independently. Berck is one of those seniors.

Fan understands the issues her clients face, but she also knows it's important to work with what's available.

"We have to work realistically," she said. "That's why SAFER is imperative to seniors. They need the subsidy. It doesn't bring the rent down to 30 per cent, but it's assistance. At this point, every penny counts."

Jonathan Oldman, executive director of the organization, agrees. But he thinks the issue of housing affordability shouldn't be considered in isolation.

"Just because you don't have a waiting list for SAFER doesn't mean everyone is getting access to it or that it's the solution for everybody," he said. "We need to think about housing more broadly, considering health support, social support and nutrition support."

As for Berck, last time we spoke she had yet to decide whether she would apply for the subsidy. She understood that at this point, SAFER would only provide a temporary fix to her financial troubles.

"I don't know where the long-term solutions are," she said. "I don't know where it goes from here. I feel like my hands are tied." ![]()

Read more: Housing

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: