In 2006, Jimmy Bundschuh, the founder and an organizer of the Shambhala Music Festival, visited Nelson City Hall and asked the mayor if the festival could use Nelson's wastewater plant.

He got an earful from the conservative, long-serving Mayor John Dooley, who told Bundschuh the festival needed to get involved in the larger community, that it should "go and speak to the Rotary Club and the Lions Club, get involved in the Hospital Foundation and help sponsor events apart from Shambhala."

"I guess I was coming to him asking for something without offering to give anything back," reflected Bundschuh.

The festival didn't get the wastewater plant, but it did get Dooley's message. At the time, the number of festival-goers equalled the population of Nelson itself -- 10,000 people -- and for a few weeks every summer was putting a strain on the city's businesses, emergency and social services. It was time to return the favour.

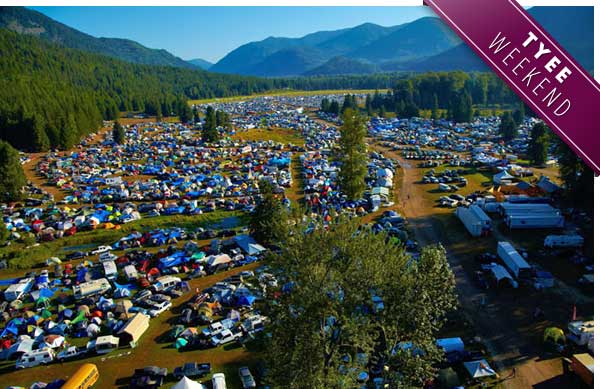

Shambhala has run over four days every summer for the past 17 years on a 500-acre farm a half-hour south of Nelson, on the banks of the Salmo River. It is one of the biggest, longest-running, and most influential electronic music festivals on the continent. The land is owned by Rick and Sue Bundschuh and the festival is run by their children, Jimmy, Corinne and Anna, as a private business with no corporate sponsorships.

Throughout the region, Shambhala has been a profoundly polarizing event, especially in its early years. Some angrily advocate that it be shut down because of perceptions of crime and drug abuse at the festival. Yet there are thousands of young (and not-so-young) people in the area and around the world who are passionate about going to Shambhala, on fire about it, for months in advance, every year.

That's because, according to Jenna Arpita, who teaches yoga classes at the festival, "people feel like they have come home" when they arrive there. "It is a place of acceptance and surrender and transparency and beauty, and every body, shape or size or colour, is welcome, no matter how you are dressed or how you dance," she said.

After his meeting with the mayor, Bundschuh decided the festival needed to "let people know we are part of the community and part of the region, and we want to see everybody do well," he said. So he dove in.

Donations catch town 'off-guard'

Shambhala started its new community involvement with a fairly conventional move for an organization so far outside the mainstream. It contributed $15,000 to the Kootenay Lake Hospital Foundation's campaign to raise $1.2 million for a CT Scanner.

"I think that was our most successful contribution to the community, because it caught a lot of people off-guard," Bundschuh said.

Then it gave the same amount to a fundraising campaign for the construction of Nelson's new outdoor skatepark.

And it began giving food and money to the food bank and a local soup kitchen, in response to complaints that the hundreds of festival-goers passing through Nelson depleted those agencies' food for weeks in the summer. It also started making smaller donations to a variety of local charitable causes.

But a big opportunity came in 2013, when Selkirk College advertised that it was selling naming rights for its new, upgraded theatre at its Tenth Street Campus in Nelson. The theatre would be given the name of any company willing to contribute $100,000. Shambhala was the only applicant.

"This created a vigorous discussion internally at the college," said Angus Graeme, Selkirk's president. "When you are giving name rights to part of your teaching facility, you are communicating that you are aligned."

The question was whether Selkirk wanted to be aligned with an event whose reputation, for many people, was encapsulated in RCMP statistics from the 2013 festival: 200 drug seizures, plus 40 service calls about "assaults, possession of a substance for the purpose of trafficking, other drug possession, trespassing, theft, mental health issues, causing a disturbance, liquor, and vandalism," with 14 people taken into custody and one to hospital, according to the Nelson Star.

That is one narrative about Shambhala, but Graeme knew there were others. He'd never been to the festival and wanted to look deeper, so he visited the site and talked to the organizers.

"I was really impressed with the leadership and the corporate vision of the organization. I went and met some festival-goers, looked at the security and harm reduction and water treatment, talked to vendors. I am not a music festival-goer myself, but I became more educated," he said.

"My recommendation to the board was we should accept this great offer, because it was a way for the festival to give back to the community in an area it is passionate about, which is young people and music."

The college's 108-seat renovated theatre, with new state-of-the-art sound and recording equipment, is now called the Shambhala Music & Performance Hall.

Graeme said there are now fruitful exchanges of talent and expertise between the festival and students in Selkirk's music program.

"The festival is a successful business in our community," he said. "If they were a multinational, what connection would they really have?"

'Cutting edge' harm reduction

Nelson's small business community can be as conservative as any other town's. Nevertheless, in 2012 the Nelson & District Chamber of Commerce gave the festival its annual Business of the Year Award.

"We looked at the economic impact of this festival," said the chamber's executive director Tom Thomson. "We looked at how well-organized it is. This was not a contentious decision."

He said the chamber appreciated how the festival put Nelson on the map for young people around the world and created local jobs and economic spinoffs.

"I am not an electronic music fan," said Thomson. "I have been to country festivals, rock festivals, folk and blues festivals, and I can tell you that at some of those other festivals there are things just as bad as people perceive are going on at this one."

"Shambhala is a really interesting study in community," said Bob Hall, whose editorship of the Nelson Star, and before that the Nelson Daily News, spanned the entire run of the festival until last year.

A parent of two teenagers, he said he often gets into arguments about the festival with other parents.

"They say, 'Would you let your daughter go there?' They seem to think they are going to be force-fed drugs and taken to a tent and date-raped. I have had people say that kind of thing to me, and that's a weak argument. It's a sign of somebody who has never been there and is unable to debate it and is playing on your fears.

"Obviously as a parent I would be concerned, like I would be concerned if kids were going to a bush party. But some people don't give young people enough credit."

Hall also thinks the festival organizers don't get enough credit. "They are doing an incredible job of creating this temporary city and making sure it is safe," he said.

"But I have several friends who are police officers," Hall continued, "and they refuse to even engage in the debate. They get very upset. But those guys see only the worst, they see only the problems."

The Salmo and Nelson RCMP declined requests for an interview. But Wayne Holland, chief of the Nelson city police, which has a supporting role in policing the festival, said, "I really do find they are well-organized and have a commitment to safety. They are aggressively against liquor. Most of the people there are a pretty mellow group."

Holland qualified this with some concerns.

"There is a vast amount of drugs being consumed, and it is close to the highway and vehicles, and that is often where we run into problems with festival-goers."

The festival doesn't allow alcohol on site and inspects for it at the gate, but like prohibition of alcohol anywhere, this is semi-successful.

Chloe Sage of Ankors (AIDS Network Kootenay Outreach and Support Society) in Nelson said harm reduction at Shambhala has progressed from a two-person team in 2002, to its current 35 volunteers.

The festival has become a "spearhead around cutting-edge harm reduction," she said. "We are the only people in Canada doing pill testing at a festival. The list of drugs we can test for is long."

Working in conjunction with Ankors, Shambhala also has an outreach team of 20 people, who wanders the festival looking out for those who need help. There is a women-only safe space. And there is The Sanctuary, which offers "psychedelic first aid."

'They care about their town'

Hall said one of the factors behind gradual community acceptance of the festival is that a local family runs it.

"The mom and dad couldn't be more average people of the Kootenays, and that is the neat thing. Their son pitches an idea, and it turns into this world-famous festival."

"They care about their town," said Salmo Mayor Ann Henderson, of the Bundschuhs. Salmo, population 2,000, is right next door to the festival.

Henderson's grandfather was the previous owner of the Shambhala farm. She used to help him with his haying when she was a child.

"He'd be turning over in his grave if he saw this," she said with a laugh. Shambhala reminds her of a 1960s love-in, she said.

The festival and the people of Salmo have had a hard road to reconciliation, Henderson said, but she thinks it's turned a corner. In the early days, following the festival, "we had people that had no way to get out of town, hanging around for a week after, sleeping on the sidewalks."

Now, she said festival organizers actively try to partner with the community.

Meanwhile, back on Baker Street in downtown Nelson, Shambhala recently bought the old Savoy Hotel, a 100-year-old three-storey building that in recent decades has had many tenants, two fires and lengthy closures.

Bundschuh and his family are doing a major renovation, and will open a hotel, nightclub and restaurant, with two live music venues featuring various genres, not only electronic. The restaurant will feature meat and produce from the family farm.

"We are taking lessons from the festival and trying out those concepts on a permanent venue," he said, adding that he doesn't want to disclose the opening date or the name, only that it will not be called Shambhala.

Mayor Dooley likes this, because the festival is putting its money back in the community.

"As mayor, I wish that old building had been fixed up years ago, and nobody came to the table to do it," he said. "And now here are these folks. They have some capital, they want to invest in Nelson, and that is fantastic." ![]()

Read more: Local Economy, Music

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: