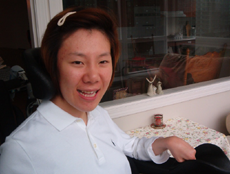

Sometimes Ji Won Park wakes up with the memory of a dream. Her mother Chun Ran (Jackie) Lim asks her questions: Was it in Korea or Canada? Was it day or night? Unable to speak, Ji Won answers with a smile (yes) or with downcast eyes (no).

"It's like our game of Twenty Questions," I comment.

"More than twenty!"

The dreams of Ji Won Park mean a lot to her mother, and they should mean a lot to all of us. She is the young Korean student who, on May 27, 2002, was suddenly condemned to life imprisonment inside her own body.

The story shocked not only Vancouver, but Korea as well: Ji Won, then a 22-year-old, was in Vancouver to improve her English before returning to Hankuk Foreign University, in Seoul, for one more semester. After graduation she planned to return to Vancouver to study event planning. Jogging in Stanley Park on the 27th, she was attacked by a young man with a long history of psychological problems, and strangled into unconsciousness.

A passer-by collared the attacker and got Ji Won breathing again, but the lack of oxygen to her brain had done terrible damage. In a coma, she was taken to Vancouver General Hospital. Within a couple of days her mother arrived to face a nightmare: a beloved daughter close to death in a strange land, cared for by people speaking a strange language.

Support came quickly. A lawyer found Jackie a translator to help her deal with the medical people looking after Ji Won. The Korean community, as well as ESL students and ordinary Vancouverites, rallied to raise money. Ji Won's brother David visited on leave from Korean military service, and returned for good after his discharge.

The local media, both English and Korean, covered the story intensely for months, and returned to it when the attacker was sentenced to nine years in jail. When Jackie, Ji Won, and David moved into a Coal Harbour apartment designed for persons with disabilities, it looked like a happy ending; the media turned their attention elsewhere.

World of agony

Almost three years after the attack, Jackie Lim sits in her living room with her children. She's a short, slender woman with wavy hair. As she recalls those early weeks, they seem very recent.

"Ji Won was in a coma for four or five weeks," she says, with help from David as translator. But that didn't mean Ji Won was just sleeping. The brain damage caused her left knee to be drawn up almost to her shoulder, while her right hand, clenched into a fist, was pressed against the other shoulder. The flexed arm and leg had to be encased in casts to straighten them out. The casts, in turn, made it awkward to move and turn her.

Early news reports had suggested Ji Won might never revive. But she did, into a world of agony. For weeks she screamed and wept, racked by pain that drugs couldn't kill. In that hot summer of 2002, sweat would pool under her body; Jackie would have to move her every hour or so, massaging her right leg especially to try to ease the pain.

Some kind of cerebral healing must have been going on, because in December, after four months, the pain suddenly ceased. At about that time Ji Won was moved from VGH to G. F. Strong Rehabilitation Centre, where she stayed until January 2003. After six months in Pearson Centre, Ji Won and the family finally settled into their apartment.

"The doctors didn't want her to leave," David recalls. "We must have gone to a hundred meetings about it." Pearson didn't allow him and his mother to spend the night with Ji Won, who was in a room with two other patients. Instead they had to show up at 7:00 in the morning, and then stay with her until 11:00 at night or even later.

"We needed some stability," he explains, "and my sister needed to get out." The apartment was a huge improvement, especially with the provision of personal care attendants and physiotherapists.

Slow progress

But the past two years in Coal Harbour have not been easy. Ji Won is making progress, in slow stages.

Much of the progress is coming from three sessions a week with Dr. Paul G. Swingle, using a technique called "neurotherapy." Successes come in surprising ways: until recently, Ji Won had to move her head to track a moving object in her vision. Now she can again move her eyeballs, following David's finger as he moves it across her face.

In addition, Ji Won has a weekly session at Pearson for hydrotherapy, working in a swimming pool. Every three months she returns to G. F. Strong for botox injections, to relieve the spasms in her fingers, legs and toes. The most recent injection was just a few days ago, and Ji Won demonstrates by briefly uncurling her left hand. Usually both hands are clenched into fists, and only when she sleeps do they relax. (Intriguingly, her hands also open when she attends services at First Baptist Church.)

Other physical problems persist. She can't move her right leg, and her left leg suffers from severe cramps, running from her knee up into her chest. The cramps, David says, are getting better. Her body temperature is low, especially in her lower legs. In her wheelchair, she needs a restraint pad over her left knee to keep the leg from lifting involuntarily. Sometimes the leg and her left hand rise when she's trying to say something; sometimes the right leg rises in her sleep.

A mixed blindness

Perhaps the most serious problem is her vision. Her eyes are perfectly all right, but the attack left her with cortical blindness. "She sees 3-D objects," David explains. "Those flowers, you, colours, light, birds flying. But she can't see 2-D, like TV or pictures or letters."

This places her in a worse position even than Stephen Hawking. The disabled physicist can compose speech and text simply by looking at letters on a computer screen. The computer tracks his eye motions and combines the letters into words and sentences before printing or speaking them.

By contrast, letters simply don't register with Ji Won, so she can neither read nor write. But her hearing is excellent, and she can follow a TV program if her brother or mother describes what is going on. "Her memory is excellent," David says. "She remembers little details from months ago, details we have forgotten." The family plans to take her to the Neil Squire Foundation in Burnaby, in hopes of finding a way to help her communicate using computers.

For now Ji Won lives a steady routine. She wakes at 7:30 or 8:00, and one of her personal care attendants cleans her in bed. Breakfast in midmorning is usually hot cereal with blueberries. A late-morning appointment with Dr. Swingle is followed by bath time, and then a physiotherapy session in mid-afternoon.

Dinner is usually Korean or Chinese food ("Whatever she wants," says Jackie), but they have to be careful: leafy foods like lettuce and spinach could catch in her throat and keep her from breathing. Members of her church come by in the evening for a couple of hours of Bible study-one night in English, the rest in Korean. By 11:00 she is in bed.

In many ways it's a very busy life, including visits from former classmates and outings in the family van. In the summer of 2003 the family learned how to transfer Ji Won from her wheelchair to the van, and took her off to visit Buntzen Lake. Since then they've been all over the Lower Mainland, with expeditions as far as Whistler and Tofino.

"We want to go to see eastern Canada," Jackie says. "Ontario, Quebec." In the van? No, says David. "We'll fly there and then drive. We're good for two nights and three days."

The future

The family takes life one day at a time, and counts each day's progress. Neither Jackie nor David thinks much about anything but Ji Won. But late last year they finally gained permanent-resident status in Canada. This gave them access to health care, and enabled David to find a part-time job in a local Korean restaurant. He's also taking a summer course at Capilano College, and planning more courses in the fall.

Jackie worked in a real-estate office in Korea, but has no plans to find work here; Ji Won is her work. "I'm not thinking about myself," she says, "just wishing for her improvement."

She shows her account of the last three years: notebooks full of Korean script, a diary beginning just two or three days after the attack. A plastic bag holds Vancouver papers in English and Korean, reporting the attack and its aftermath. One story describes a happy encounter in the Hotel Vancouver with Queen Elizabeth, who took the gift of a lily from Ji Won's hand. Some day, Jackie hopes, these records will be the basis for a book.

Through a morning's conversation, Ji Won herself is an active participant. A "yes" is a karate punch of a smile. A half-lifted left hand strengthens the "yes." The lowered eyelids of a "no" are emphatic. At times she listens and then withdraws, evidently thinking about what we've said. Sometimes she makes small sounds, trying to form words. Jackie and David interpret; I am learning "Jiwonese," but I am just a beginner. For now, I am simply struck by her sheer presence -- a tall, slender young woman who commands attention. She is not confined to her wheelchair, but enthroned in it.

In two worlds

"We don't know everything that Ji Won has inside," Jackie says. "She's isolated from the world."

"Lots of things in her mind," David agrees. "We can sense them." But he senses the gap as well: "We see scenery, we play sports-we can enjoy them. But my sister can't jog, exercise, watch movies, and we need to share these things with her."

That means sharing bad times as well as good. "This has left some emotional scars," Jackie says. The stress of the past three years has been intense. "But we have no secrets," David says. "We never lie to my sister."

The conversation turns again to dreams. "Sometimes she dreams," says Jackie, "and she says a lot in her dreams. They tell a story." On the mornings when Ji Won has had a dream, her mother asks the questions, more than twenty, to learn the story.

Some day, somehow, Ji Won Park will tell that story to all of us.

Crawford Kilian, a frequent contributor to The Tyee, has created a blog about Ji Won Park and her family at crofsblogs.typepad.com/jiwon/ ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: