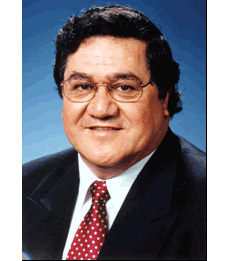

Graham Hingangaroa Smith has a bold vision: to see 250 First Nations students graduate from B.C. universities with PhDs by 2010. Smith is no dreamer. He's a hard-headed academic whose work in New Zealand revolutionized Maori education-and produced 500 Maori PhDs in five years.

If the province adopts some of the strategies used in New Zealand, Smith thinks it will reach this goal. His prescription? Open more First Nations immersion schools, galvanize the Aboriginal community to embrace education as part of the fabric of everyday life, and use First Nations communal ties and other "cultural capital" to overcome social disadvantages.

"It would be a very large jump" to graduate 250 PhDs in five years, "a huge task," according to Linc Kessler, the director of the First Nations Study Program at UBC. Last year only one doctorate was awarded a First Nations student at the special ceremony held at the Long House. However, Kessler said perhaps there were Aboriginal students elsewhere in UBC who never came to the attention of the organizers of that graduation.

In fact, one of the immediate problems facing Smith is establishing the exact number of Aboriginals who hold, or are working on their PhDs in the province. Juanita Berkhout, coordinator of Aboriginal programs for the Ministry of Advanced Education, says neither the province nor universities track the number of PhDs granted First Nations students every year. Nevertheless, Smith has identified 27 First Nations doctoral students at UBC this year.

First steps

Although he has only taken up his position as distinguished scholar of indigenous education at UBC this September, Smith has already persuaded the university to launch a new centre of excellence, The Indigenous Education Institute of Canada. The institute's mandate is to create a critical mass of First Nations scholars, and to research ways of strengthening Aboriginal education at all levels.

Smith works out of a bright office cluttered with piles of papers and shelves of books. Currently on leave from his job as Pro Vice-Chancellor (Maori) at the University of Auckland, Smith speaks in soft Kiwi cadences, and describes the revolution in Maori communities and culture over the past 20 years. "The revolution that occurred, the essence of it, was actually a change of mindset. It was a shift from Maori being reactive to what's happening to us-and always being on the defensive-to being proactive about what we wanted and being assertive about going after it and doing it." In the early 1980s the New Zealand government adopted some policies that worsened existing inequities between Maori and non-aboriginals, Smith says, but others opened the door to new opportunities, especially in education. "What the government said was every New Zealander must have choice about the type of education that they want. The Maori-some Maori-put up their hands and said, "Excuse me, we want a Maori-language choice, and it's not here.'"

Language revival The new Maori schools focused on reclaiming their language, still spoken widely in rural areas but dying among Maori city dwellers. "These schools arose in the urban setting. They arose out of Maori parents who had lost the language themselves," he says. Maori schools offer both "mainstream" and indigenous education. "The Maori struggle," says Smith, "has been for excellence in Maori language, knowledge and culture, which is still important to our communities and our society, as well as access and excellence in world knowledge." Because these schools reject the proposition that students must either assimilate fully into mainstream culture or totally embrace indigenous culture, students are able to fit into both the Maori and the wider world, he says. Students follow a curriculum that is related to their cultural background, language, and knowledge, but the values of their heritage are embedded into every aspect of school life. Maori, for instance, place a high premium on communitarian principles, so this is accorded a prominent role in everything from financial and personal relationships. "When two parents over here are unemployed in this household, it doesn't matter that they can't afford to pay for their kid to go on the school trip," Smith says. "Those that didn't put in any money know that they must do something else in return for the community. They may well come down to the school and clean the windows in the school because they have time on their hands to do that. When there's a domestic upset in a home environment, these schools operate as extended family: they will remove the kids and place them with other families. Or if a kid comes to school with no lunch, it doesn't matter because everyone puts their lunch on the table anyway. Everyone eats."

Beyond government funding Although "there's oodles of evidence" linking poor marks at school with the kind of poverty common in First Nations communities, Smith says there's no point in waiting for the government to hand-over fistfuls of to change the situation. "The cargo plane's not going to land and the state is not going to deliver on its own," he says. Instead, First Nations need to use their own abundant cultural capital-a strong community ethic-to blunt the effects of privation on their children's academic performance. The Secwepemc (Shuswap) Nation near Chase involves its members in an immersion school that it opened almost 20 years ago. Inspired by the Maori model, Kathy Michel helped found the Chief Ataham School, and continues to teach there. "Learning the language enhances students' understand of the world: it makes them see the world in two different ways," she says.

Students are immersed in the Secwepemc language in day-care and pre-school even before they start school. And as in New Zealand, elders work closely with the students, teaching them the traditional knowledge of their people.

"Elders come in and teach them about plants, animals and our culture. They learn how to listen better, because they are learning in the target language." More than half of the graduates of the Chief Ataham School have gone on to post-secondary education. "The benefits are just amazing," Michel says.

Pride and politics For the Maori, immersion schools have helped nurture not only cultural pride but also social and political networks, which have in turn fostered political mobilization on many issues, Smith says.

Although the government has been generally supportive of Maori schools, recent education policy changes have curtailed immersion enrolment, causing long waiting lists.

"I think the government realized that they'd opened the floodgates," Smith says. "That was a learning point for us because what we learned, was that the so-called free-market was always up to a point, but if the power relations or economic elements got out of kilter, then those who held the power could change the rules." But it's not just the elementary and secondary schools that need to change. Instead, Smith prescribes a radical restructuring of university education and aboriginals' relationship to it. In New Zealand, Smith instituted "learning communities," where universities "do all the traditional things that universities do -- promote the language and culture of the area -- but it also intervenes in a whole range of community contexts." So, he says, elders are encouraged to come to the university to take courses, enabling them to informally transmit their language and culture to students just by virtue of their presence.

Key to civilization In B.C., Ed John, the Grand Chief of the First Nations Summit, also dreams of having a First Nations university to promote the development of his people. "Every civilization that has survived has had institutions of higher learning to support and develop the knowledge and learning of that culture." Smith believes that First Nations' cultural health depends on developing a critical mass of well-credentialed indigenous intellectuals who are prepared to plough their social and intellectual capital back into their community. "What we're trying to do," he says, "is to produce academics who have a consciousness about working for others." To increase the odds of Maori graduate students' success at university, Smith has developed a mentoring program for them. A unique aspect of this program is its ten-day writing program, made available to students finishing their doctoral dissertations: students are packed off to a five-star hotel, equipped with all the amenities of both a university office and a luxurious retreat. There, they devote days to writing, and evenings to long dinners with each other--and prominent New Zealanders.

Challenges to optimism In Canada, Smith says he has seen many praiseworthy examples of First Nations education, so he's optimistic that he'll achieve his goal of 250 First Nations PhDs within five years. However, he doesn't mince words over what he sees as some of the shortcomings of Aboriginal education. "Overall, I'm pretty disappointed with the Canadian situation," he says. "The first point here is that Canada is the wealthiest economy in the commonwealth per capita, income per capita. But it's also one of the top ten economies in the world. And yet, its per capita expenditure in the area of First Nations is pretty abysmal." One of the biggest obstacles in the way of Smith's goal, however, is access to university, according to John. "Our biggest problem is getting students into university in the first place, because there aren't enough spaces," he says. "It's a political problem that has to be dealt with." And students who manage to find a spot at university face challenges in staying there, he says. "At the University of Saskatchewan, 47 per cent of first year Aboriginal students drop out in their first year. That's staggering." Jo-Ann Archibald, a UBC professor and interim director of the fledgling Indigenous Education Institute of Canada, says financial difficulties are a significant issue for First Nations students. "It's very, very hard," she says. "I think that financing, especially with rising tuition, is difficult." However, Archibald remains optimistic that B.C. Aboriginals can overcome these hurdles. After listing Smith's achievements in New Zealand, she comments that sometimes it takes an outsider to introduce changes that have been made a difference somewhere else. "That's very inspiring," she says.

Judith Ince is on staff at The Tyee, with a special focus on education. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: