Ken Frail of the Vancouver Police believes strongly in Canada's guiding principles of "peace, order and good government." But the veteran inspector in the VPD's Planning and Research Department fears that the B.C. Liberals' next round of welfare cuts, beginning April, will produce the contrary--and in doing so, gravely undermine Vancouver's innovative strategy for dealing with the city's severe drug problem and those afflicted by it.

"Right now I'm looking at a marginalized population that is going to be really destabilized by the cuts that government is making," says Inspector Frail. "I understand what the government is trying to do, but when supports are removed and other agencies are forced to retreat, we become the last agency standing--and these cuts are going to affect what we face on the street."

April 1 is the next big deadline in the provincial government's three-year strategy to reduce welfare. On that day, British Columbians who have received income assistance for more than two years out of the previous five, and who are deemed employable, will be bumped off the rolls or see their monthly cheques reduced sharply.

Nobody knows exactly what will be the impact, because B.C. is the first Canadian jurisdiction to introduce such a rule and the Minister of Human Resources, Murray Coell, has refused to provide estimates of how many people will be affected until later this month.

But for most of the fall, in Vancouver at least, trying to assess those impacts has been a top priority for city officials, police and outreach workers. And fears are now growing that one of the biggest casualties could be the success of the Vancouver Agreement, recently signed by the feds, province and City, and the innovative Four Pillars strategy to deal with Vancouver's severe addiction to drugs.

Province invested $10 million in Pillars

"The cut-offs are an arbitrary measure that mark a fundamental shift in social policy," says Jeff Brooks, the City of Vancouver's director of social planning. "Besides driving more people on to the street, to food banks and social services, this and other welfare changes will increase the burden of police and health care workers.

"The spin-off effects could also be harmful, undermining public support for drug treatment programs and the Four Pillars."

Those Pillars represent Prevention, Harm Reduction, Treatment and Enforcement: the components of a new strategy that aims to balance a mix of progressive initiatives such as culturally sensitive prevention programs, supervised injection sites and needle-exchanges and more treatment beds with conventional priorities such as putting more police on the streets.

Among the main supporters of the strategy is the Liberal provincial government, which is responsible for funding all the pillars except Enforcement. The provincial government has matched the federal government's investment of $10 million in carrying through the Vancouver Agreement. Announcing that investment last April, provincial Minister of Community, Aboriginal and Women's Services George Abbot claimed the spending proved "a commitment to create a legacy for the Downtown Eastside as part of our 2010 Olympic Bid."

Why then would the Campbell government introduce welfare reforms that could erode the Four Pillars?

The welfare cuts will do nothing of the sort, according to a spokesman for the Ministry of Human Resources. He notes that the government has taken pains to exempt the most needy from the cutoffs: those fleeing abuse, those with dependent children, those with medical conditions that make them unable to work, and so on. And he is quick to point out that it is spending $300 million over three years on employment and training programs to help people get off income assistance. To date this has helped 24,000 people get off welfare and into jobs, he says.

"We want to provide people with the supports they need to earn more money than they would on income assistance and to be better able to care for themselves," the spokesman says.

Fearful scramble to get estimates

Those assurances do not calm the fears of those trying to implement the Four Pillars. They envision a contrastingly dark scenario after the welfare cut-offs: An expanded population of the poor and addiction-prone cut loose from family and government support networks, drawn to the Downtown Eastside's supply of hard drugs and services.

Such fears motivated Vancouver City Council to pass a motion November 4 urging the province to rescind laws imposing Income Assistance time limits and reducing benefits.

Front-line workers meanwhile have been scrambling to help vulnerable people gain exemptions from the time limits, and to assess just how many people will be subject to the new rules

A leaked document obtained by MLA Jenny Kwan indicates that in October 49,576 British Columbians on welfare were considered employable by the Ministry of Human Resources. Ministry officials, however, have said this document is misleading. Instead, it estimates that as of October, just 29,939 people on welfare were "expected to work," with 6,722 of this total in Vancouver. The Ministry warns, however, that the caseload for welfare is always in flux, so it unwise to draw conclusions from the current numbers.

One thing is certain: the cut-offs are a central part of a three-year plan to slash the annual budget of the MHR by $580 million, from about $1.9 billion in 2002 to about $1.2 billion in 2005.

Much tougher to get on welfare

The impact of the cut-offs is supposed to be gradual, as each month a new cohort of welfare recipients will be bumped off the rolls or find less money on their welfare cheques. (Single mothers with dependent children under 3, for example, who have been on IA for 24 months will receive up to $100 less).

Together, however, with other new rules announced in April 2002, the cutoffs will likely contribute to further big reductions in welfare. These include a two-year independence rule, which requires first-time applicants to demonstrate that they have supported themselves for at least 24 months (rather than living at home with parents, for instance).

Another change removed a provision that allowed welfare claimants to earn up to $100 a month on top of their cheques. (A single person earns $510 a month on income assistance: $325 for shelter; $185 for other support.)

At the front-end of the system, meanwhile, more onerous procedures for claiming welfare are reducing the stream of new IA recipients. For example, now a person who shows up at a welfare office must make an appointment with an income assistance officer for three weeks later. In the meantime, the person is sent away with documents telling how to look for a job. The person must return to the welfare office in the interim to watch a video telling about B.C.'s income assistance system. Miss an appointment and the person's file is closed and it's back to square one.

"Overall caseloads are going down, but not because more people are coming off welfare," says Seth Klein of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. "Exit surveys done every six months by the government after people get off welfare indicate that the there hasn't been a significant increase in the number of people leaving welfare. Rather, far fewer people are gaining income assistance for the first time."

Again, it is difficult to assess how many are being turned away at the welfare door, as MHR does not keep this statistic. But outreach workers say that the numbers are significant and people are becoming increasingly desperate.

Bending truth to satisfy system

Take, for example, the young woman who spoke up at a small meeting in December arranged by Mayor Larry Campbell to hear from street youths about how the City might help the more than 700 young Vancouverites who are homeless, addicted to drugs and destitute.

The articulate 19 year-old told the mayor that a bit of income assistance would allow her to quit panhandling and get off the street. When her claim was rejected, she found herself with one option--convincing a doctor to write a letter claiming that she was a heroin addict and, therefore, eligible under a special category. She said that she was not a heroin user, and was incensed that she had been forced to tell this lie --and, as a result, would have to undergo treatment for an addiction that she did not have.

The mayor reportedly expressed surprise and said that this was absurd; but front-line workers say the system is producing many such absurdities while at the same time creating barriers that will prevent many of the neediest from gaining assistance.

Mill workers displaced by the softwood lumber dispute, out-of-work fishermen, mentally ill people with drug addictions, Aboriginals and young people: these are some of groups who will be hardest hit according to Liza McDowell, a legal advocate at the Downtown Eastside Women's Centre. And McDowell believes that many will wind up in her neighbourhood, Canada's poorest postal code district.

Adding to a problem population

"Youth booted out of abusive homes by their alcoholic parents, for example--what are they going to do?" McDowell asks. "They are not going to have access to welfare for at least two years. Those with proper nutrition, good health and a modicum of education can find McJobs or something better--but lots of kids coming on to the street don't have these basic things and not all of them can be baristas."

McDowell says there is not nearly enough training and support programs for youth and that many young people will give up hope and resort to sex work or drugs. "Remember, crack cocaine is free for young women, young men who are new on the street--at least, until they're addicted."

This funneling of people into the troubled Downtown Eastside could pose a significant public health risk if recent history is a guide. In the late 1990s, reductions in public housing and the closure of mental institutions sent vulnerable new groups of people to the neighbourhood, where they found support services and cheap housing as well as ready means to "self-medicate." Together with other factors, this fuelled an outbreak of HIV that infected 2,000 injection drug users--and ranked Vancouver among the worst hit urban areas in the global AIDS pandemic.

Among other things, this public health disaster motivated Vancouverites to vote for the Four Pillars. But life on the street seems to be getting uglier again. Aggressive panhandling and scavenging is on the rise.

The thriving market in crystal methamphetamine is leading to new levels of violence. And emergency shelters such as the Salvation Army's Harbour Light on Cordova are being overwhelmed b y numbers of people seeking help.

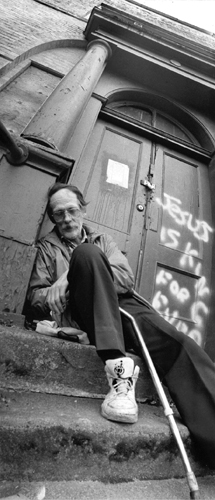

Over a month ago, at First United Church on Hastings at Gore, about 25 people were sleeping on the pews and floor of the chapel and for the first time in its history the church was attempting to stay open 24 hours a day to accommodate more people. Church staff and volunteers, meanwhile, were struggling to deal with the lengthening line-ups for their free coffee and sandwiches, and those in the lines were becoming more unruly: throwing punches, whereas a year ago an exchange of harsh words was as rough as it got.

'To Hell with it' factor

"We're bracing ourselves for a much greater call on the kinds of aid that we provided in the past: food, shelter and advocacy,"says Stephen Gray, a community advocate at First United.

Gray blames the deteriorating situation in part on the new difficulties people have in getting income assistance, as well as the government's more intense verification regime.

"People living on the street have trouble satisfying the verification process. It's difficult because they may prefer not to say what they've been doing or it is impossible to prove how they have been surviving. If they get on to welfare, they have to develop a work plan that they stick to, promising to send out so many copies of their resume, and going to x number of interviews. Often, though, they don't have the resources to carry through on their plans, not even bus money to get interviews. As a result, people often get discouraged and say 'To Hell with it,' then they're back off welfare again."

This is what most strikes fear in supporters of the Four Pillars. As one says "As soon as you take away a person's ability to eat, to get shelter and gain access to basic health care, how can you expect them to be in a state of mind where they will be able to seek treatment for their drug addiction?"

Inspector Ken Frail of the VPD expects that the cuts will push many residents out of cheap single room accommodation hotels and into the street. Here they will be joined by new groups of homeless and addicted people who have been displaced from other municipalities.

View from a 'bubble'

They may come from places like Surrey, where the council has refused to invest in emergency shelters and hiked the fee that it charges pharmacist who dispense methadone -- a replacement therapy for heroin addicts--from $200 to $10,000 per year.

Don McPherson, Vancouver's Drug Policy Coordinator and one of the authors of the Four Pillars Strategy, shares Frail's concerns.

"We are concerned that welfare changes could have a negative impact the on the Vancouver Agreement, given the lack of hard numbers from the Ministry, and the fact that the economy is not good," says McPherson.

"We have this feeling of being in a bubble that's pushing its way upstream," he says. "We have small successes -the safe injection site, the Life-Skills Centre, health contact centre and so on-but the really major changes seem to be going against us."

Jim Boothroyd, a former reporter and editor for the Montreal Gazette, is a Vancouver-based freelance writer who also works as a communications manager in HIV/AIDS and health outcomes research. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: