Naked, chilled and immersed in the sea of Genkai, I have little more than my stiff-upper-lip British heritage to conceal my modesty.

Seven not-so-young male biologists from four different countries and several conservation organizations are with me on the island of Okinoshima, participating in a Shinto ocean cleansing and purification ceremony.

Back in Canada, my 11-year-old daughter declares the moment "awkward" while examining the photographs. Her analysis is upgraded to "awkward, but okay" when I explain the significance of Shinto belief in Japanese society, and how the modest ceremony captures the essence of a rapidly emerging global effort to re-wild the planet.

The 80-hectare island of Okinoshima lies 50 nautical miles northwest from Fukuoka, in southern Japan, on an ancient trading route with Korea. It is deeply revered by the Japanese, for it's there the ancient Shinto gods gave three empresses to watch over and safeguard the nation. Their presence is immortalized in an enclave of sacred boulders surrounded by verdant Japanese cedar trees, reflecting a Shinto tenet that all life is sacred, respected and revered.

Areas of particular importance are shrouded by a Shimenawa, a hemp or natural fiber rope from which pure white folds of paper (shides) are hung, symbolizing purity. The entire island is held sacred by the Japanese nation, and consequently, everything that enters the island must be pure.

As the Shinto priest explains the cleansing ritual, a distinct hint of mirth plays in his eyes. Two small bows and two claps followed by a frigid submersion leaves us cleansed. Given my personal history, I repeat the process for good measure. Appropriately purified, we are free to explore.

Islands at risk

Kanmuri Umi Suzume, the endangered Japanese murrelet, is the catalyst that brought us to this remote subtropical island.

There are only an estimated 30 breeding pairs left on the island, and less than a thousand throughout the archipelago. Sporting a distinct tufted crest, the bird is similar to the ancient murrelet of Canada's West Coast.

The decline of the birds is a direct consequence of an invasion of predatory rats. The loss of murrelets marks the beginning of the islands inevitable trophic collapse as the rats work their way through the islands biodiversity -- a clarion call for remediation.

Kuniko Otsuki, of the Japan Seabird Group, has created a distinguished team of international experts to help assess and develop a recovery strategy.

Collectively, they have saved countless numbers of bird species and restored numerous islands throughout the Pacific region.

Globally, over the last 500 years, 80 per cent of all extinctions have occurred on islands as a result of the deliberate or inadvertent introduction of invasive species.

Feral goats, cats and rats are the usual suspects. Island life is different than continental life, primarily because of a constrained number of species and the absence of pressure from predators or vegetation-grazing mammals. Consequently, islands are ill-equipped to respond to rapidly changing habitat or predation.

Of 8,000 islands globally impacted by such invasions, an estimated 500 are amenable to rehabilitation.

Island Conservation, a global network of conservationists and biologists based in Santa Cruz, orchestrates rehabilitation of islands on a global stage and has set its sights on saving or contributing to the remediation of these 500 in the next decade. Okinoshima is a candidate.

The team assembles

Our journey to the island started several months ago, with flurries of diplomatic overtures and information requests to gain access.

Okinoshima is ordinarily off-limits. Shinto mythology forbids women to grace the island and unnecessary visits are strongly discouraged by the Shinto priests. It is a rare privilege for me to accompany the biodiversity assessment team.

Arriving in Tokyo, the city of cities, is overwhelming. After a long journey from B.C., I was met at the massive Shinjuku station by a sea of incomprehensible hieroglyphics and waves of densely packed people. The team is in Tokyo to acclimate, and spend several days in meetings with key conservation groups to discuss the challenge ahead. No island restoration is the same -- the ecology of each island is as complex as the societal constraints that prevent rapid restorative action.

BirdLife Japan, an organization that advocates for the protection of endangered birds in the region, hosts us for discussions in a quiet Tokyo suburb the following morning. Talk revolves around the important Asia Pacific bird areas, and the complexities of habitat protection. Despite the depressingly familiar story of habitat loss, it is encouraging that in a region fraught with political tensions, Korea, China and Japan are working constructively to protect endangered birds, like the migratory Chinese crested tern.

The journey continues by bullet train to Fukuoka in southern Japan for it is the closest mainland departure point for Okinoshima. I am glued to the window, and the blur of an industrialized and urban landscape that never stops for over 1,500 miles. Clearly, this is a nation that has very little natural habitat and, like Europe, is coming to realize the importance of a biodiverse world -- notions that seem less and less familiar in Canadian policy, where the land mass is still regarded as infinite resource field.

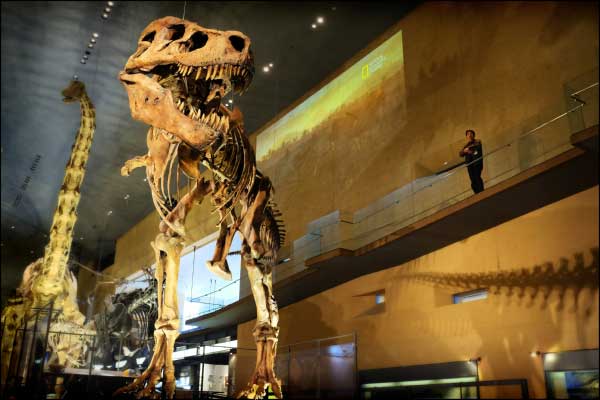

In Fukuoka, we meet as an expedition team for the first time. Dr. Masayoshi Takesishi, or Masa, the expedition leader and project proponent, hosts a series of technical meetings at the Kitakyushu Museum of Natural and Human History. It's spectacular. The dinosaur hall offers an array of specimens charting the evolutionary trajectory of life, death and extinctions. As Masa pulls stuffed specimens of Japanese murrelets from the archives and herds us to a barren meeting room, it becomes clear that he has no intention of letting this bird wink out on his watch.

A rat invasion

As the weather eases, Yoshinobu Miyasaka, the captain of the Ebisu II, confirms our charter to the island. A tense wait is suddenly replaced by the frenetic packing of gear and supplies. Stocky, with a distinct air of renegade, our commercial fisherman/skipper has quite the reputation. He's a local legend who single-handedly invaded North Korea to protest territorial fishing incursions, until he was declared insane and sent home.

As Fukuoka and southern Japan slip below the horizon, Okinoshima's isolation becomes apparent. A skinny oval, the island is clothed with a canopy of subtropical trees and sports a rugged 300-metre spine with rocky outcrops. With the exception of a lighthouse, a modest shrine and harbour, the island remains as it has always been.

Landing is straightforward, for despite the ocean swells the harbour is substantially over-engineered. Built during the Korean War as an outpost to protect the nation, the construction allowed the rats to secretly invade. With abundant food and no competition, the rat population exploded. The island's trophic collapse, albeit in its infancy, is beginning to build momentum.

Early on, the team realized that success at Okinoshima could be elusive.

Second generation anticoagulant baits, highly effective and humane rat poisons are not licensed for use in Japan. Furthermore, the packaging for helicopter delivery of the bait is far from ideal. In other regions of the world heavy and light baits guaranteed to reach the forest floor or get caught in the canopy are available. But in Japan the bait must be wrapped in a light paper bag -- perfect for being windblown out of a target area. Although predation by rats is the direct cause for the loss of Japanese murrelets on Okinoshima, and while eradication is mechanically straightforward, Masa gently reminds us that culturally the Shinto belief system respects all life.

Shrine priests will need to consider the course of action carefully, for both rat deaths will occur and poison will be introduced within the "pure" Shimenawa of Okinoshima.

The first expedition

Ravenous, we break out lunch while Masa reiterates the plan of attack. In total, four rat and mouse trap lines will be set and recovered at high, mid and low-level elevations. Two oceanic night sea bird surveys seeking the elusive Japanese murrelet and chicks are planned. And there will be a search for murrelet burrows and possibly chicks on the nearby islet of Koyashima.

Masa leads the expedition from the harbour to the lighthouse at the island's southern peak for a biodiversity assessment, necessary to ensure that eradication methods won't impact non-target species.

The lighthouse vista is spectacular, yet utterly devastating to the visiting biologists. Dotted around the island's shoreline, clinging to precarious outcrops, are handfuls of sports fishermen. Due to the treacherously inaccessible coastline, the Shinto priests are powerless to enforce the island's strict visitation rules. Boat traffic, unfortunately, means the ready re-invasion of rats. A single breeding pair of rats can produce over 5,000 descendants in a year; a cascade of offspring that makes eradication a futile effort. Simply, more island traffic means repeated re-infestations.

As we crawl through the subtropical forest setting trap lines, light soil slowly eases under our shirts and coagulates with sweat. It is not long before I am fantasizing about a second voluntary ocean cleansing.

After several hours in the thick understory we have covered little more than a kilometre at best, yet as we grind on Olivier Langrand becomes increasingly ecstatic.

A bird expert who has personally observed over 8,000 of the world's known 12,000 birds, Langrand is amazed at the number of birds he has identified in such a short visit. His enthusiasm is palpable, believing he has heard the call of the rare island wood pigeon, one of the world's rarest birds.

Yet sequestered in the undergrowth, the ominous signs of predation are present. Masses of feathers without carcasses point to the presence of Peregrine falcons. When carcasses do appear they are chewed to the bones, indicating rats.

A ticking clock

As dusk falls, we return to camp for a brief respite before we start the oceanic night surveys. Supper will be sea bream sashimi, fish broth and rice. The sashimi melts in my mouth, and I can't help but wonder if this is some of the last wild food on the planet.

Conversation returns to the protection of Okinoshima's biodiversity. Gregg Howald's initial assessment is that the island is an ideal candidate for eradication. The biological constraints are similar to many islands that have been recovered.

But the clock is ticking. The rats have attacked the very foundation of the island's ecology and inexorable collapse is underway. The easy prey, the small defenseless murrelets, their eggs and chicks, are almost gone. As the rat population swells on the abundant food, the ingenious predators will target the island's biggest food source, the streaked shearwater colony.

The loss of shearwaters would impact the island's biological productivity in complex ways. The waters that surround Okinoshima are rich sport fishing grounds. Every day, 30 minutes after sunset, a colony of 200,000 shearwaters literally descends upon the island. Long-winged oceanic gliders crash land into the treetop canopy and tumble through the branches till they reach the ground. It is the most undignified homecoming, accompanied by an infernal cadence as the birds commune, squawking and crowing, and seek the sanctuary of their burrows.

The birds play an absolutely crucial role in nutrient cycling. They collectively fertilize the soil by depositing vast quantities of nitrogen and phosphorus laden guano. Sequestered in the soil, the nutrients promote a diverse range of terrestrial plant and tree life. The vegetation yields fruits, seeds and nectar that draw an abundant bird population to the island.

Like a sponge, the island also slowly leaches these nutrients into the surrounding ocean. This catalyzes the near-shore ecology, producing plankton and coral reefs, and ultimately, the thriving reef fish that are highly prized by the sports fishermen that troll the island's shoreline.

Explaining the dangers and inspiring self-regulation so that certified rat-free ships become a point of honour to protect the world-class fishing would be an effective preservation route. Co-aligned, the fishermen and the Shinto priests could easily ensure a biodiverse Okinoshima endures.

Night survey

As we board the Ebisu II for the ocean night survey, Olivier encourages me to look skyward. Barely perceptible in the twilight, seemingly fleeting in and out of existence, ghostly glimpses of shearwaters circling high above the island can be discerned; thousands of birds floating in the great aerial ocean.

Daryl, the seabird survey expert, briefs us that we will circumnavigate the island twice. The goal is to determine the presence or absence of murrelets and, hopefully chicks too.

It is a stomach-lurching endeavor. As the darkness envelopes the boat, despite the vague glow of the distant industrial fishing fleet, it is impossible to read the confused swell. Clinging to the gunnels and my cameras, I watch Daryl sweep the ocean with a powerful light from the bowsprit, scanning for bundles of feathers the size of a baseball.

Murrelets travel vast distances offshore foraging for food, but at night congregate in rafts, often in the lee of breeding colony islands. As the search enters the second hour, the searchlight picks out a few adult birds. A few fleeting glances are just sufficient to identify them before they either duck dive or take off at high speed into the inky black night. Over the course of two circumnavigations a kilometre offshore, 30 observations are made, all adults but no chicks. It's not a good sign.

Raining birds

At base camp, I grab a bivouac and march off looking for a spot to sleep where I can hear the wind in the trees and waves crash on the shoreline. I'm awoken hours later by a 3 a.m. dawn chorus, a raucous cacophony more like the streets of Tokyo than a paradise island, as the shearwaters rise to start the day. 30 minutes later, I abandon all hopes of sleep in the increasing crescendo. Crawling out of my sleeping bag, I resist the urge to stomp on a luminous arthropod the size of a giant cockroach that crawls out with me. It wanders off nonchalantly looking for a new warm bedmate. One more to add to the species list.

Picking up my camera gear, legs already heavy, I strike out for the heart of the shearwater colony. Entering the colony, I am abruptly bombarded with birds. By the time the fifth or sixth bird has flown into my face, I realize the problem. I quench my headlamp; the birds mistake the light for a viable flight window in the predawn darkness. Stumbling by feel up the trail, eventually I find a natural window in the canopy.

Here, the birds are congregating and literally climbing into the trees. It is the most inelegant of clambering, but once they gain elevation it allows a fully-extended wing launch into the prevailing wind. Birds that can climb trees from the forest floor! It is a remarkable island adaption that allows the shearwaters to utilize forest habitat that would be a death trap for their albatross cousins.

As the sun grazes the horizon, silence suddenly envelopes the island, for the entire colony has vacated the island for distant fishing grounds.

The day unfolds, once again, grinding through the undergrowth recovering traps we set the day before. Five traps contain the biggest well-fed rats I have ever encountered.

Takuma believes both Rattus rattus and Rattus norvegicus rat species are present. DNA analysis will confirm his observation. As the rats are humanely euthanized with ether, Masa, a man of deep Shinto convictions, is solemn in the moment. He remarks that it is deeply regretful but necessary that a life must pass.

Night falls, and skipping the last ocean murrelet search I climb into the shearwater colony to meet their evening arrival. At some point along the trail, the noise becomes absolutely deafening and it literally starts raining birds. With discombobulated wings thrashing in all directions to break their fall, they tumble through the branches to the ground. Yet as suddenly as the dawn chorus ended, after an hour of communal discussion, a collective decision to sleep occurs and silence envelopes the forest.

Returning to camp, I am met by a joyous team. The distinctive bundle of fuzz, a Japanese murrelet chick, was observed. Masa is thrilled to confirm breeding on the island. The chick, barely two days old, has successfully survived rat and peregrine predation and reached the sanctuary of the open ocean.

One last hike

Our final morning is as rude and raucous as those before. Grudgingly, I drag myself to the island's peak in the hopes of a spectacular sunrise over the sea of Genkai. My hopes are denied as a bank of cloud rolls in. I trudge back to camp and the inevitable grind of loading the boat. But the Shinto priest, Yasuhiko Sugiyama, has asked if I will accompany him to the shrine and share in his daily devotions. Inwardly my body screams at one more ascent; outwardly I graciously accept a very rare privilege.

As we climb the trail, we quickly establish we cannot converse -- we share not a single common word. Yet along the trail that I have traversed multiple times, he points to nuances and details to which I have been oblivious. Perhaps his quiet commentary echoed in his formal rituals at the shrine reveal the very essence of Okinoshima, the island Shimenawa where the intricacies of life, culture and ecology intersect.

As I rush back for the boat, I bump into Olivier. Absolutely thrilled, he draws my eye to his spotting scope, and a rare Japanese wood pigeon, resplendent in the trees, can be seen.

Okinoshima, shimenawa indeed. ![]()

Read more: Travel, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: