"When the Chinamen saw all these men coming, they were terrified. The crowd came up to the camp singing 'John Brown's Body,' and such songs; the Chinamen poked their noses out from beneath their tents; the 'rioters' grabbed the tents by the bottom and upset them, the 'war cry,' 'John Brown's Body,' still continuing. The Chinamen did not stop to see; they just ran. Some went dressed, some not; some with shoes, some with bare feet; the snow was on the ground and it was cold. Perhaps, in the darkness, they did not know that the cliff, and a drop of twenty feet [was there]; perhaps some had forgotten; some may have lost direction. The tide was in; they had no choice; and you could hear them going plump, plump, plump, as they jumped into the salt water. Scores of them went over the cliff -- McDougall was supposed to have two hundred of them up there." -- Eyewitness W.H. Gallagher. Early Vancouver, Volume One.

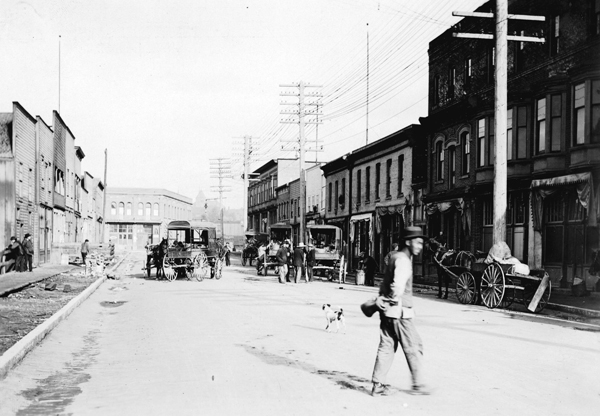

This past Sunday marked an overlooked but instructive 126th anniversary. On Feb. 24,1887, a little over a year after it was incorporated, the city of Vancouver experienced its first full-scale race riot. It was a sudden explosion of violence as much economic as it was xenophobic; a group of close to 300 white workers, fearful of losing work to inexpensive foreign labour, and whipped into a frenzy by inflammatory speeches delivered from within the city municipal building, marched on a camp of Chinese labourers at the foot of Burrard Street, destroying more than $2000 in property, and running hundreds of workers out of town.

The event was by no means unprecedented. In fact, one of the city's earliest recorded racial clashes took place on the same day as its first election, as 50 or 60 Chinese voters brought from Victoria to support candidate R.H. Alexander were rounded up by a mob and sent back on the first steamship (some even run down by a stagecoach). John McDougall, the contractor responsible for the project, was no stranger to the hostility directed toward his workforce; less than a month earlier, his crew had been run out of town, forcing him to sneak them back into the city by way of New Westminster.

"The Canadian Pacific Railway was finished in 1885," explains David H.T. Wong, architect, advocate, and author of Escape from Gold Mountain, a graphic history of the Chinese in North America. "They had all of these unemployed Asian men and women roaming around, and they started taking work in the forestry and mining industry, and it became a competition for resources, in terms of jobs. And at that time, there was a lot of agitating going on going on down in California, and it headed northward to B.C, saying 'the Chinese are taking our jobs.' And, when people are squeezed... the economics are just an easy way to find a scapegoat."

"When the Chinamen came to Vancouver from Victoria they knew they were not wanted," local pioneer W.H. Gallagher explains, in an interview with archivist J.S. Mathews, "they came in the face of opposition -- some Victoria Chinamen refused to come, and perhaps that knowledge helped to terrify them."

The labourers were in the employ of contractor John McDougall, who had been hired to clear portions of Samuel Brighouse's land (much of the modern-day West End). However the contractor (known derisively by locals as "Chinese" McDougall) was already widely loathed for his use of inexpensive Asian labour -- particularly since in order to gain the contract, it had allowed him to undercut competitor H.P. McCraney by approximately 50 per cent. McDougall himself remained in Victoria for the duration of the incident -- luckily, as it turned out, considering there was talk by the mob of tarring and feathering him.

Whipped into racist frenzy

It all began on the morning of the 24th: a sign was paraded through town, reading: "The Chinese Have Came [sic]. Mass Meeting In The City Hall To Night". The labourers had only been back in town for only two or three days before they were discovered, keeping a low profile on a large portion of vacant land near the foot of modern-day Burrard Street. By 8:00 that evening, the municipal building was a seething mass of bodies, with speakers declaring that action must be taken -- a position backed by prominent local business interests. However, by the end of the meeting, the crowd whipped into a frenzy by racist rhetoric, no concrete plan of action had been formed, and it quickly became clear that speeches wouldn't be enough.

"Those in favour of turning out the Chinese to night say 'Aye,'" called out a voice.

"To this there was an unanimous response," explains the Feb. 25 edition of the Vancouver Daily News-Advertiser, "the word being on every man's lips, and when the noes were called for the audience were so quiet that a pin could have been heard to drop."

With this, the crowd surged from the building, a few lanterns in hand, singing and chanting, and picked their way along the lengthy, difficult trail to the Brighouse lands.

"That would be well on towards midnight; there was snow on the ground; it was quite clear and we could see what we were doing," W.H. Gallagher explains. "There were many tough characters among the crowd, navvies who had been working for Onderdonk, hotheaded, thoughtless, strong and rough, and many went along with the procession to try and prevent anyone from being hurt."

"On arriving at the Chinese camp, which lies about a mile west of Granville street, past the C.P.R. grade, the mob immediately surrounded the shanties and amidst howls and yells commenced the work of seizing the Chinamen," explains the News-Advertiser. "A number got away in spite of their efforts to surround them. Those who were caught were in some instances badly kicked by some of the crowd, and then ordered to pack up and leave, in which they were assisted in no gentle manner."

The crowd attacked with such ferocity that many of the labourers simply turned and fled, leaving behind their belongings, which were immediately put into a pile and burned. Tents and shanties were pulled down, and added to the blaze.

"It was a weird scene to those standing on The Bluff, and looking down on the fire," reported the Feb. 24 edition of the News-Advertiser, "inside which were burning the bundles of clothing and bedding, which were thrown down from the hill from time to time, whenever the fire grew dim and appeared to require replenishing."

Police dispatched

By this time, local law enforcement had been notified of the disturbance, and the mob, confronted by Chief Stewart and Superintendent Roycroft, seemed to lose much of its enthusiasm. Within minutes, the crowd had dispersed. Throughout the night, several shacks were set alight by zealous protestors, and there was talk of raiding Chinatown, but otherwise the violence remained contained. The following morning, with the exception of one merchant left to watch over each Asian-owned business, every one of the city's Asian inhabitants was packed into a wagon, and sent back on the first steamship to Victoria. Some were said to have been tied together by their pigtails to keep them from escaping.

The response from the provincial government was swift; after three quick readings, a bill suspending the city's charter was passed, and, within days, Superintendent Roycroft arrived with a contingent of 38 heavily-armed special policemen. The force was met with jeers and open resistance from locals and city officials, and even Mayor Malcolm McLean did his best to delay and disrupt the proceedings.

"Superintendent Roycroft's force landed on the C.P.R. dock," explains Ormond Lee Charlton, one of three agitators arrested in the wake of the riot, "uniforms, and arms" (revolvers and batons), "blue serge uniforms; it had taken two or three days in Victoria to outfit them, and Smith and Weston five-shooters. Notwithstanding the fact that Vancouver was in a state of 'riot,' the superintendent demanded of Mayor MacLean the 'keys of the city,' and the Mayor said, 'Where is your authority?'"

Three rioters -- Ormond, Tom Greer, and logger John Frauley (all of whom had been charged by city police, but never convicted), were brought before Judge A.E. Vowell, but due to a lack of evidence (and cooperating witnesses), the charges were quickly dismissed.

"It was stated in court that the two ringleaders had gone to bed comparatively early in the evening, and had not left each other during the night, which was true," pioneer W.F. Findlay explains, in an interview with archivist J.S. Matthews. "They had gone to bed comparatively early, got up again and gone to the riot, and then returned to the Sunnyside, and gone to bed a second time."

Within weeks, the labourers were back at work -- this time under the protection of a team of special constables. Both McDougall and the Asian labourers involved fought back through legal channels, holding the city responsible for damages to their livelihood and workforce. There is no evidence that either amounted to anything. And the incident, while by no means the beginning of anti-Asian sentiment in the area, set an ugly precedent which would lead to years of violence, intimidation, and indifference to Asian citizens by everyone from locals, to the highest levels of the provincial and federal governments.

In 1907, the city's best-known race riot laid waste to much of Chinatown. Over the decades, the federal government would collect upward of $23 million in Head Tax from Chinese citizens, before the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 effectively halted arrivals from China altogether. In 1925, houseboy Wong Foon Sing was kidnapped and tortured on orders from the provincial attorney general, for his suspected involvement in the death of a Shaughnessy housemaid. And, in the 1940s, owing to strong pressure from prominent Vancouver advocates, the federal government opted to intern all 21,000 members of the province's Japanese community, despite having no evidence of suspicious activities.

Forgotten citizens

Attitudes have changed in the ensuing decades. In 1988 and 2006, the federal government issued official apologies for its part in both Japanese Internment and the Head Tax -- in the latter case, paying out $20,000 to each survivor or living relative. Human rights committees (or in B.C's case, a Tribunal) exist in every Canadian province, for the express purpose of dealing with cases of discrimination. But, while Wong admits that society itself has become generally friendlier, in terms of the attitudes that underscored the 1887 riot, and all subsequent outbreaks of xenophobia, he isn't convinced that much has changed.

"They had this gigantic forum about five years ago, where Premier Campbell, and all these 'experts' talked about the 'Green movement', and greening buildings, and all that sort of stuff," he explains. "And they had about 40 or 50 people on this panel, talking about Asia, and the rise of China, and the great opportunities in Asia, and on and on they went. And all the organizers were white guys. And all the guys on the panel were white guys. There wasn't a single Asian face there, in Vancouver, a city where 40- to 50 per cent of people have Asian or south Asian ancestry.

Wong continues, "The Canadian Pacific Railway celebrated the anniversary of the Last Spike in 2010 at Craigellachie. And they invited all these guys from Ottawa, they all flew in there, and all these bigwigs from all over the country. Then again, they're celebrating the whole completion of the C.P.R, but there wasn't a single Asian guy there. And when you think about the Chinese contribution, they helped unite Canada, and they did it four years ahead of schedule." ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: