Yvon Raoul, now 76, was fined in December 2020 for chaining himself to a tree to stop logging on the pipeline route near the Brunette River.

Some months later, in August 2021, Yvon went to Fairy Creek, where eventually over 1,100 people would be arrested in what was the most extensive act of civil disobedience in Canadian history. Yvon and seven other activists attached themselves to a concrete barricade for 24 hours in an effort to save threatened old-growth forest.

“And then,” Yvon says, “the RCMP came with jackhammers. They gave us helmets and something to protect our faces, but the drilling with the jackhammer was pretty loud and there were sparks.” Once the cops had detached the demonstrators from the concrete, Yvon was released without any charges being laid. When he noticed that his companions were given court dates, he asked whether there had been some mistake in his case.

“Well,” he was told, “you’re placed in a special category called ‘catch and release.’”

“What do you mean? I’m not a fish!” Yvon joked. He was relieved and happy, but at the same time disappointed. “Why would you do that?” he asked.

The cop said, “At your age, we don’t want a problem with you being arrested with high blood pressure and having a heart attack.”

Yvon comes by his activism honestly. It has its roots in France, during the Second World War. It has its roots in the story of his father.

A great escape

It was early September in 1943. Alain Raoul was on a train in Alsace-Lorraine hurtling towards Buchenwald, Germany. The young Frenchman was not Jewish; he was a political prisoner. His destination was a notorious death camp, from which very few people were released. But with some luck, his acute powers of observation and daring, events took a surprising twist.

Just three months earlier, Alain had been living in Épernon, a small town 90 kilometres southwest of Paris. Alain, then 20, was distributing an underground newsletter for the French Resistance and “doing all kinds of things that did not please the Germans,” Yvon says. He also worked in a factory that produced cement casings for bombs.

As acts of sabotage had started to occur, German guards oversaw the operations and Alain chafed under their constant vigilance and suspicion. One day, a guard Alain particularly disliked upbraided him for a misdemeanour. Alain responded by gesturing threateningly with a hammer.

Alain was hustled off to a jail in Orléans, where he was imprisoned for a month. “Then,” Yvon says, “he ended up in a transit camp run by the Germans.” He was sent to Royallieu-Compiègne, north of Paris, the second-largest such facility in France. More than 50,000 people passed through its gates from 1940 to 1944: Jews, Resistance fighters, trade unionists, political activists, foreign nationals. Only 4,000 of these people, less than 10 per cent of the total, survived the war. Alain was incarcerated in the camp for six weeks. Then, he and 946 other prisoners were told that they would be leaving — by train.

The terminus of the journey was to be Buchenwald.

On Sept. 3, while waiting on the station platform to get on the train, Alain carefully observed how the sliding wooden doors of the railcars were closed. He saw that a metal bar was lowered into a slot and a piece of barbed wire was used to secure the bar. By luck, no keys were involved. Another piece of luck was that one of Alain’s companions in the car, a Spaniard who had been fighting against then prime minister Francisco Franco, had managed to hide a pocket knife in his shoe.

This was enough for the two men to hatch a plan for escape. Once the train was underway, they began to whittle.

Not everyone in the car approved of what they were doing, Yvon says. Some thought that making a small hole in the door couldn’t possibly lead to escape. A wasted effort. Others believed that attempting to get away was far too dangerous; it would lead to certain death. Still others, who did not intend to escape themselves, didn’t want anyone else to attempt it either. They were afraid of reprisals.

By evening, Alain and his friend had succeeded in creating a hole big enough for a hand to pass through. Alain reached through, removed the barbed wire and lifted the bar. There was an alarming crash as the doors parted. Many in the wagon panicked; they wanted to prevent their fellow prisoners from escaping. People began punching each other.

With the melee whirling around them, Alain and a few others stood in the doorway, stunned by the fresh air gushing in. They stared into the moonless starry night as the train clattered along the track. Then, as Yvon writes in a book he published for his friends and family, “while shouting, ‘Merde aux Boches!’ and ‘Vive la France!’” they jumped. More people followed.

A searchlight played over the track as Alain scrambled up an embankment. He could hear dogs barking, people yelling, machine gun fire. He was wiry and reasonably fit. For half an hour, he and three companions ran together, striving to put as much distance between themselves and the train as they could. Then the four escapees split up.

Alain didn’t know how many men would be sent on their trail. He had no idea if anyone might help him or where he should aim to go. But he had another piece of luck. He was in Lorraine, a contested area that had passed between France and Germany several times since 1870. While Germany had re-annexed Lorraine in 1940, all its residents were French.

Alain met people who, at great risk to themselves, gave him directions and provided food, places to rest and lodgings for a night. Without their help, he might not have survived. While taking refuge in a nunnery, he learned that 11 people had been killed the night he escaped from the train.

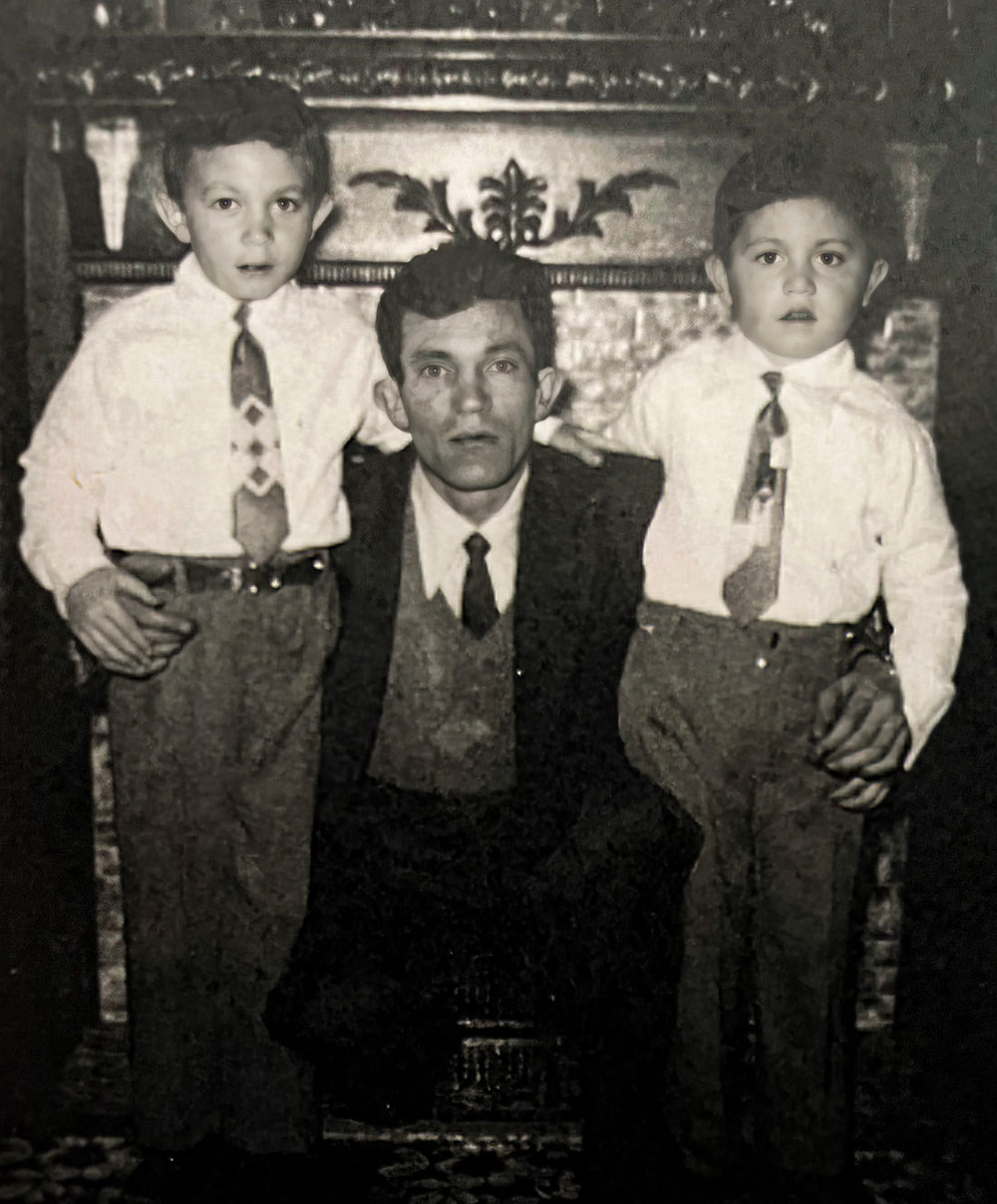

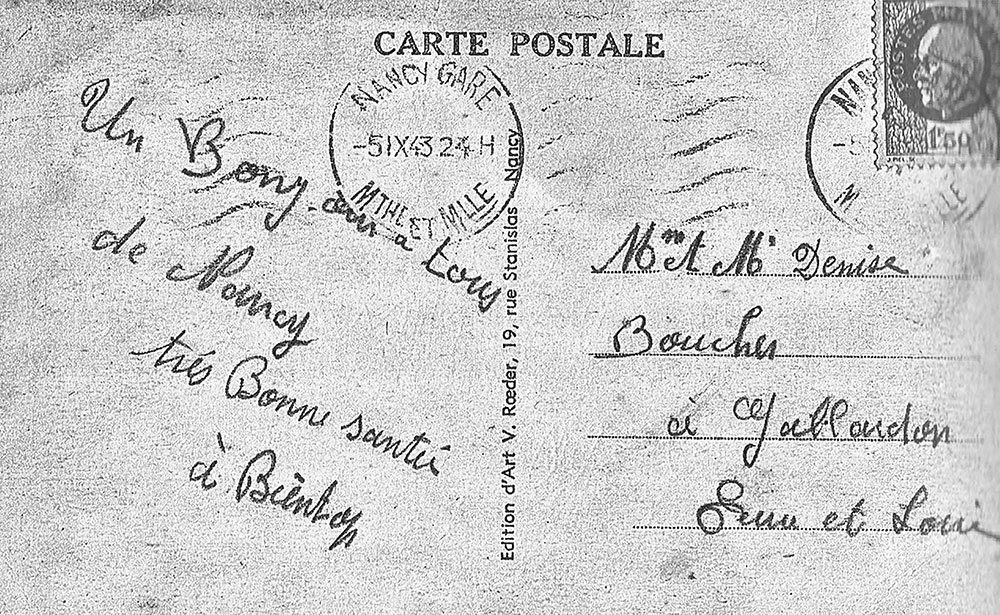

A baker gave Alain money so that he could buy a train ticket to Paris. Alain walked to Nancy, a riverfront city in northeastern France. At the train station, he bought a second-class ticket. He also bought a postcard and sent it home. On Sept. 5, 1943, Alain wrote, “Un bonjour à tous de Nancy” (Hello to everyone from Nancy). His family and friends must have been overjoyed to read the cryptic message.

In his book, Yvon writes that one of his favourites parts of his father’s story occurred after he boarded the train for Paris. With his second-class ticket, and a certain insouciance, Alain made his way into a first-class compartment, where he was surrounded by German soldiers, also on their way to Paris. They were smoking and Alain hadn’t had a cigarette for months. Despite his precarious situation — he had no identification papers — he asked one of the soldiers if he could have a cigarette. That soldier gave him a whole package.

Alain managed to slip through the ubiquitous identity checks and made it to Paris. He stayed with one of his cousins for a month, recovering from his ordeal. After procuring false papers, he went to Brittany, France. He joined the Resistance and was trained in sabotage with British and French paratroopers.

Not many people escaped from the trains heading to the death camps. Historian Tanja von Fransecky was able to put a number on just how few people were able to do it. In her 2019 book Escapees: The History of Jews Who Fled Nazi Deportation Trains in France, Belgium and the Netherlands, von Fransecky writes that just over 750 Jewish people got away. They represent a tiny fraction of the many millions who were transported to their death on railcars.

Alain’s legacy

It is clear, through this story of a plucky young man who with a pocket knife defied the odds and outwitted the powerful Nazi war and terror machine, why Yvon’s father was such an influence on him.

“I always had political consciousness because my dad was very involved with unions, with left-wing politics. A leftover from the Resistance,” he says. This was in Quebec, where the Raoul family eventually settled after immigrating to Canada in the early 1950s, and where Alain found work as a bus driver.

Yvon became a schoolteacher and married Valerie, who became a university professor. They moved to B.C. in 1979 with their two children. (A third was born out west.) Shortly after Yvon arrived on the West Coast, he had what he called a “road to Damascus moment.” It actually occurred on a road, on Highway 4 near Kennedy Lake on the way to Ucluelet, while the family was on a camping trip.

“I was absolutely shocked by the contrast between the dreamlike beauty of the place and seeing the clearcuts all along the way. Nothing was hidden. And from that point on, I think I was pretty much vaccinated as an environmentalist,” Yvon says.

Years later, that experience prompted Yvon to take up civil disobedience. He got involved with Clayoquot in ’93, helping to blockade logging roads during what became known as “the War in the Woods.” He was detained and sentenced to 28 days of house arrest.

When he was teaching, Yvon hung protest banners on the walls of his school gym. Coca-Cola was allowed to set up vending machines that sold only its product in the school and Yvon objected. This earned him the wrath of the principal, who barked at him, “Raoul, see me in my office,” just as if he were an unruly student.

For several days in 2001, Yvon and Yanish Maté locked themselves in a steel cage in front of the Vancouver Aquarium to persuade the administration to free the captive orcas.

In 2014, Yvon was arrested with his wife, Valerie, on Burnaby Mountain, while protesting Kinder Morgan’s expansion of the Trans Mountain pipeline.

Late in 2017, he joined a group ironically named “the Justin Trudeau Brigade” who also opposed this project. From time to time, over a period of several months, members of the group blocked company traffic into the marine terminus of the pipeline.

Yvon told me that on a particularly dark, rainy January morning in 2018, one of the cops who was monitoring the protest brought him a cup of coffee. Another time he engaged an officer in conversation and explained why he was there. “I totally respect your respectful protest,” the cop said. Despite these moments of rapprochement with RCMP members, Kinder Morgan named Yvon and 14 others in a multimillion-dollar lawsuit in March 2018.

More recently, Yvon and Valerie hosted a Palestinian refugee, Mohammed Alzaza, at their place for eight months after he first arrived in Canada. When Mohammed moved out, they stayed in touch.

Yvon visited Mohammed in hospital while he was recovering from knee surgery. He needed to have some injuries repaired that he had received during a bombing raid on Gaza when he was 15. Yvon found Mohammed chatting away in Hebrew to two visitors who had been helping him settle into life here. This is just the kind of incongruity Yvon appreciates — the enduring way that people can reach across political and other barriers to see each other’s humanity.

Yvon dreams of peace in Gaza. “Look at what Europeans have managed to do 80 years after butchering each other over centuries, or what Northern Ireland has done to bring peace in a land where the IRA [Irish Republican Army] and Loyalists were at each other’s throats. I believe that peace is possible because there is no other choice. Hate and racism are unsustainable passions that destroy the human spirit,” he says.

“Here in Vancouver, we have the perfect model of co-operation between Jews and Muslims in this small Independent Jewish Voices group. Mohammed, in spite of what happened to him, celebrated Seder with a friend of mine and his family.”

Yvon adds: “I do things because of the environment and because of my kids. But it’s also because in some ways, I want my kids to perpetuate what I’m doing. I want them to share its very key importance in my life. Those values are essential and I want my kids to continue with them. They give meaning to life.”

Yvon’s father died in 1992. Through Yvon, the reverberations of his leap of faith so many years ago ripple on. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: