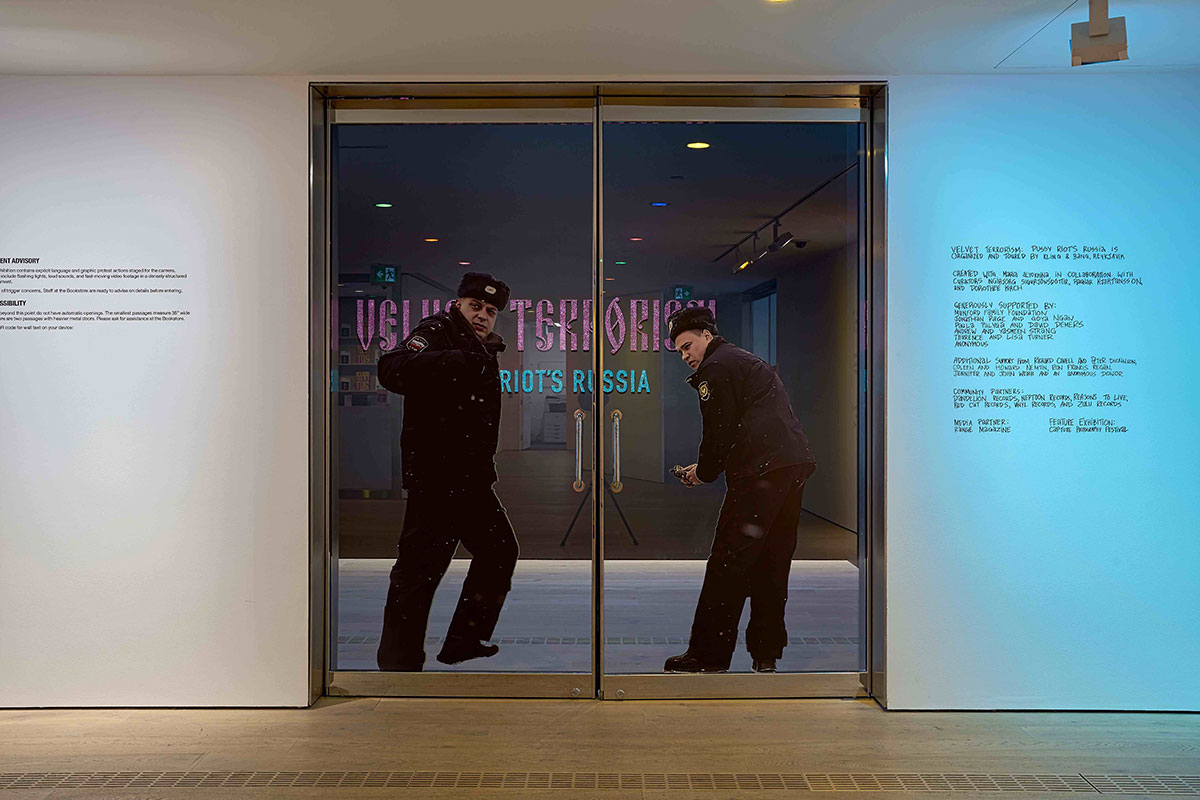

It seems fitting that the opening of Velvet Terrorism: Pussy Riot’s Russia was loud, chaotic and a little overwhelming. Punk rock en plus.

The Polygon Gallery’s new exhibition on the Russian feminist punk rock and performance art collective Pussy Riot takes its title from a statement by Russian Orthodox Church bishop and writer Tikhon Shevkunov. After Pussy Riot’s first arrest and trial in 2012, Shevkunov — widely considered to be Vladimir Putin’s unofficial spiritual leader and confessor — declared, “This is a new reality of our life: ‘velvet terrorism.’”

Shevkunov’s words establish the strange backdrop against which Pussy Riot and their supporters thrash. The convergence of an increasingly brutal fascist establishment, in concert with orthodox religion, proffers a focus for their kick-ass activism, garnering the attention of the world in the process.

It’s always something of an odd experience to partake of activism in a gallery setting. In the case of Pussy Riot, dial this oddness factor up to 11. The juxtaposition of Polygon Gallery members and donors drinking free wine while taking in the horrors of Russian history was a bit disconcerting, to put it mildly. But maybe that is exactly the point.

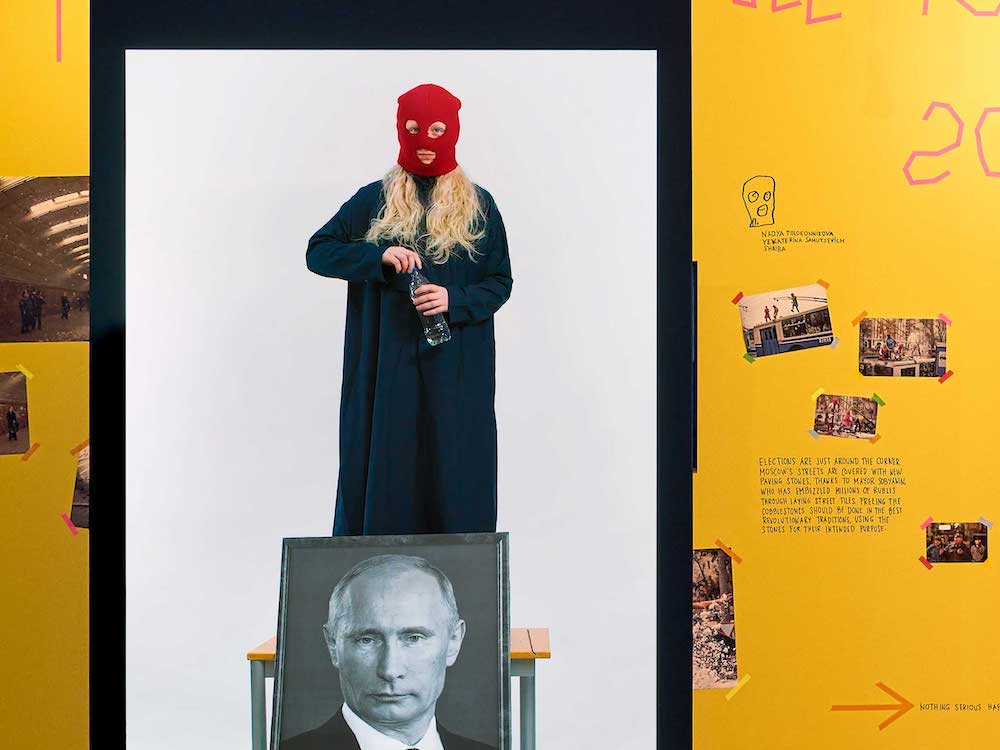

The video that launches Velvet Terrorism captures this curious dissonance in a single image. A woman dressed in the group’s trademark balaclava swigs heartily from a bottle of water, hikes up her long black dress and proceeds to pee vigorously, and I do mean vigorously, on an official portrait of Putin, before casually kicking the framed photograph of the country’s president to the side.

It’s a suitable introduction: raw, raging, but with an element of puckish, punkish humour.

Where art and atrocity collide

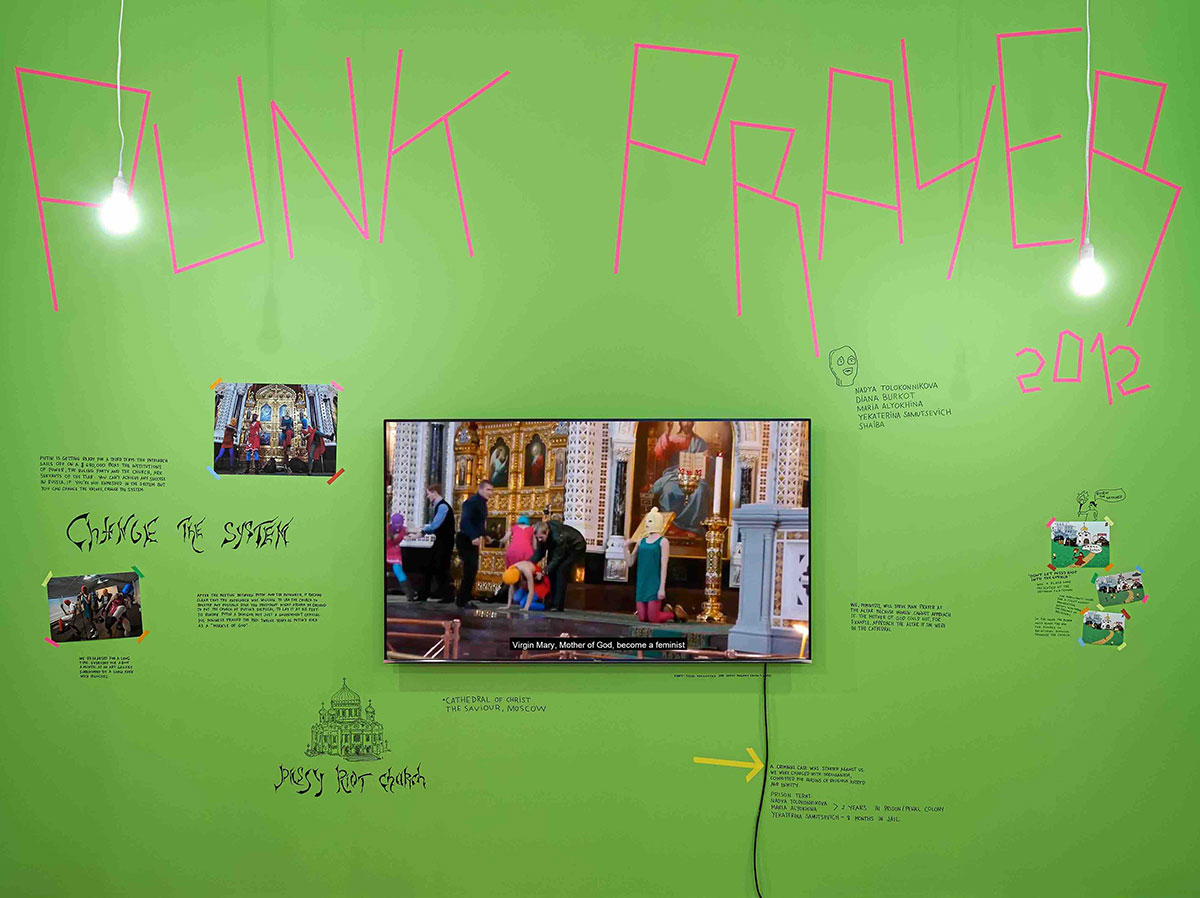

Founded in 2011, Pussy Riot initially took shape as a punk feminist art collective and performance group. Over the years, the number of members has expanded and contracted. Their guerrilla-style actions brought the group a level of attention and notoriety, but it was their landmark 2012 performance of the protest song “Punk Prayer” inside the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow that vaulted them to global attention.

The performance was part of a Pussy Riot protest against the church’s support for re-electing Putin in 2012. The group took over the nave of the cathedral and screamed feminist anthems until security forces dragged them from the church and three members were arrested. Maria (Masha) Alyokhina, Nadezhda (Nadya) Tolokonnikova and Yekaterina Samutsevich were all arrested. Alyokhina and Tolokonnikova were sentenced to two years in prison.

Following their arrest, the members of Pussy Riot became a cause célèbre, with other artists and organizations taking up the call to free them.

As the first survey exhibition of the collective’s actions and performances over the years, Velvet Terrorism is encompassing. The sheer volume of information — 55 videos, hundreds of photos, news articles and other material — in the show is an indication of the bedrock commitment of the women involved, as well as the wider movement against authoritarian forces in Russia.

The installation itself is meant to echo the experiences of the Pussy Riot members. The work takes us through their arrests, incarceration and activism, bloody but unbowed. Claustrophobic, oppressive and discombobulating, it’s also wildly galvanizing. To its credit, the exhibition goes beyond recent events and deep into the roots of Russia’s dramatic and violent history, showing how the country has been riven with internal tragedy for centuries.

In one section of the show, there is a wall dedicated to some of the architects of the country’s internal purges: photos of po-faced men who were collectively responsible for the death of thousands of their fellow citizens.

It was this part of the show that gave me the most pause, maybe because within the confines of a gallery, the juxtaposition of carnage writ so large in a cultured setting makes for a strange kind of cognitive dissonance. Whether art is even capable of contending with this level of atrocity isn’t certain, but often it’s the only weapon that lasts.

A chance encounter, and an urgent exhibition

Velvet Terrorism originated from a chance encounter between Pussy Riot member Alyokhina and artist Ragnar Kjartansson. The pair met in Russia, when Kjartansson was organizing another exhibition there in a major gallery, located between the Kremlin and what became known as the Pussy Riot Church (a popular moniker for the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, where they performed the historical set that sent two of them to jail).

In explaining his fascination with Russian history, Kjartansson cites the work of the 19th-century history painter Ilya Repin, whose depiction of Ivan the Terrible and his dying son was vandalized twice, once in 1913 and again in 2018. That a painting could invoke such violence is a reminder of the innate political power of art.

Kjartansson’s film installation The Visitors was deemed one of the most important artworks of the 21st century by the Guardian. Pussy Riot’s Punk Prayer came in at No. 4 on the list.

It was an auspicious coming together of the two, but not an immediate arrangement. Alyokhina wasn’t certain about the idea of distilling years of activism into a documentary-style art show. But over time, it became clear that a touring exhibition was a formidable means of explaining to the world exactly what was taking place inside Russia.

Alyokhina and Kjartansson teamed up with artist Ingibjörg Sigurjónsdóttir to create Velvet Terrorism. The show premiered in Iceland at Kling & Bang, an artist-run space located in Reykjavik, before touring to Denmark, Montreal and now North Vancouver. In each subsequent iteration, the team has added new items to the exhibition in response to the developing situation in Russia.

Not long before the show opened at the Polygon, anti-corruption activist and Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny was murdered in a Russian prison.

Not just Russia

At the Polygon Gallery for Velvet Terrorism’s opening, Alyokhina led media and gallery members in a winding exploration through the labyrinth of the show. The visual barrage of taped-up words, images and infographics was dense, packed onto every available bit of space. At times, it was also impossible to hear what Alyokhina was saying. The video screens, mic feedback, people talking — it all felt appropriate to the punk ethos.

Alyokhina is a small woman with long ringleted hair. Dressed in a black fringy skirt, she doesn’t look like she could survive a good stiff wind, but the women in Pussy Riot are tough almost beyond comprehension. They’re also fearless in a fashion that makes other political artists seem tepid by comparison.

This particular quality makes its presence known throughout, whether it’s the members dressing in the lime-green outfits of a food courier company and waltzing out of a building under surveillance by the authorities or launching paper planes at the offices of the Federal Security Service, a monstrous building that has come to be the face of the current regime.

With more than 50 actions since the group’s formation, a few notable events leap out. Although Punk Prayer may have garnered international attention, it was only the beginning, and in some fashion, the group’s arrest and imprisonment became a formative experience.

As Alyokhina explained, the court case and sentences took her by surprise. She was sent to Biysk, a penal colony in the Ural Mountains, almost 4,000 kilometres from Moscow.

Penal colonies, a legacy of the former U.S.S.R., are in essence work camps, facilities where prisoners work 12 to 14 hours per day, sewing police and army uniforms. For their labour they’re paid $3 to $4 per month. During her sentence, Alyokhina was able to expose the conditions with help from a human rights delegation. For her efforts, she was moved to another facility. The time in prison became the impetus for her book Riot Days.

As she explained in an interview with NPR, this period forged a deeper understanding of the nature of struggle: “These decisions become the most important ones you will ever make because you can’t forget anything you do here within the prison walls. Once you betray yourself, even a single time, you can’t stop. You become another person, a stranger to yourself.”

In advance of the Sochi 2014 Winter Olympics, the members of Pussy Riot, along with other detained activists, were freed. The women immediately undertook another action where they were beaten with whips by Cossacks who were hired to provide security for the event. As the brutal violence escalated, Alyokhina understood that the rules had changed, she says.

One of the most fascinating things about the show is the relationship between activists and the state itself. At Alyokhina’s artist talk at the MAC gallery in Montreal, this connection was described as non-consensual. As action begat reaction, authorities found themselves becoming a key part of the work — in essence, the element that completed the performance art loop. The theatricality of this reminded me of Adam Curtis’s 2016 BBC documentary HyperNormalisation, which explicates how the state used similar tactics to shift the very nature of reality.

The difficulty in even getting a handle on the constantly mutating nature of life in Russia is considerable. It’s tempting to want to simplify this struggle into easy binaries — progressive against conservative, the past and the future — but the actions undertaken by Pussy Riot and their network of supporters make clear that something seismic is in the mix.

Extrapolate the internal conflict in Russia to global struggles, and something extremely unsettling emerges. As Alyokhina made clear in her talk to the audience at MAC in Montreal, the show and its implications are not confined solely to Russia. Similar things are happening everywhere in Europe, the United States and, yes, Canada.

“I really want you to know this, and I really want you to be aware of this, and I really want to remind you that this regime is not just going to keep Russia under repression or attack nearest countries. They also raise up ultra-right movements in the West and they did it with the United States,” Alyokhina told the audience.

“They raised a lot of ultra-rights in Europe, and they’re going to continue. So, if you like some of our actions, you will have a chance to repeat them here in your own way.”

If that sounds a bit ominous, you’re exactly right. But the other thing that’s clear in this work is that real revolution needs humour, courage and a good dose of punk rock.

‘Violet Terrorism: Pussy Riot’s Russia’ is at the Polygon Gallery until June 2, 2024. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Politics, Art, Music

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: