- Dinner on Monster Island

- HarperCollins (2024)

As children, some of us were more afraid of bedtime than others. Our parents would check under the beds and behind the closet doors to confirm that there were no monsters lurking around, waiting to prey on us.

But as we got older, we began to realize monsters weren’t always fictional. Some of us recognized the monsters in ourselves and in others.

Through this process, some of us have come to see that monsters aren’t monstrous at all. This rings true in the horror genre, especially for women and queer characters. Below the gore and terror in a horror film, each so-called monster is not so different from its viewers: they are people living through hardship, people who have been ostracized. People who deserved protection but received none.

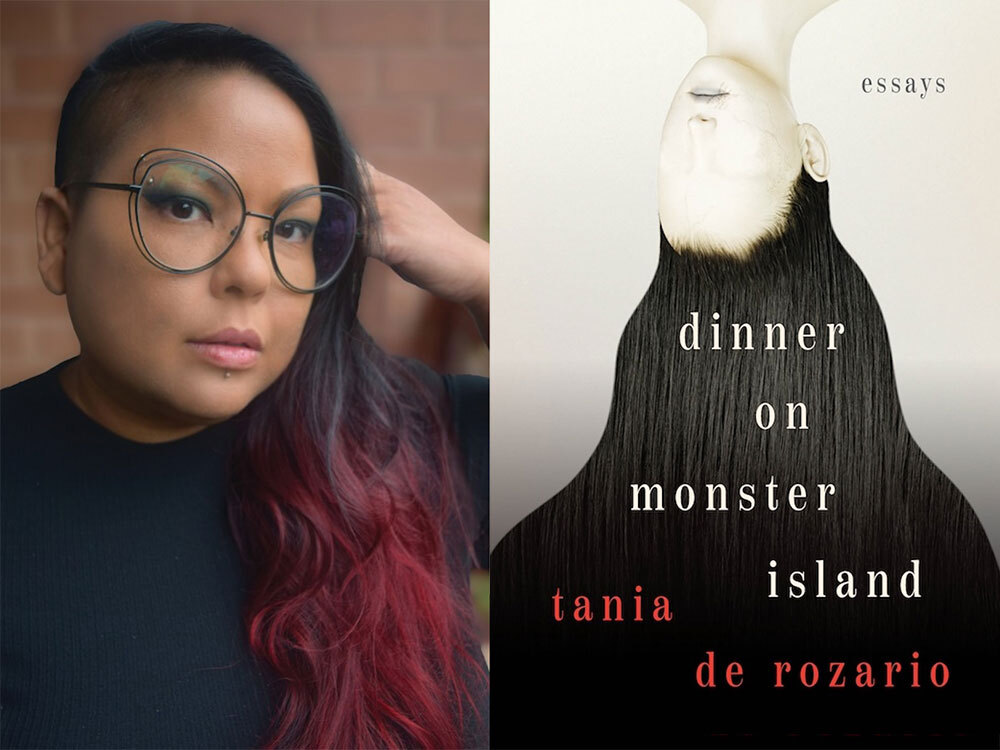

In Dinner on Monster Island, Vancouver-based writer and artist Tania De Rozario recounts memories of her childhood, her queerness and the traumas inflicted by her religious mother, whose homophobia led to Rozario leaving her home and biological family.

The book is an essay collection that weaves accounts of Rozario’s life alongside captivating analysis of the roles women play in beloved horror films. Each essay invites the reader to ponder interesting questions: What makes a person a monster? How and to whom is queerness, fatness and non-whiteness so monstrous?

In the essay “Letter to My Mother,” Rozario writes, “The minute I understood my trauma had currency, you stopped being my mother and started being material. This icy attitude is how I survived.... this wintery ability to milk you for all you are worth.”

The anger and grief that shape the work open the door towards a new sense of self-knowledge and, ultimately, a resolve to embrace the parts of oneself that were once rejected and shamed.

As Rozario’s new book hit the shelves this month, The Tyee caught up with the author to discuss family, writing and what monsters are really telling us. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Tyee: Your memoir, Dinner on Monster Island, was refreshingly honest and raw. I want to start with the final essay in your book, “Letter to My Mother.” I had to sit with that because it was so real. I felt your anger, your resentment and your grief. Could you walk me through the writing process?

Tania De Rozario: I love that you referenced this essay when asking about the process of writing this collection because even though it’s the final essay in the collection, it is the first one that I wrote.

When I went back to school in 2018, the very first assignment I got was from one of my non-fiction professors. In summary, it was to write a letter to someone. My mother died that same year and we had a lot of unresolved issues.

I had left my bio-family’s home 15 years prior without telling anyone who lived there that I was not coming back. And I had only seen her once since then — at a funeral. So the experience of returning to that house — especially since everyone else I’d once lived with there was now dead — was quite strange. And that experience was what the letter ended up being about, and where the collection started.

In terms of what elements were difficult or cathartic, I am not sure that those two experiences are mutually exclusive. I believe that the act of writing is itself cathartic, regardless of whether or not you’re writing non-fiction — there is pleasure and release from extracting a story or experience or feeling that is stuck in your head or in your chest, and putting it on paper. This process of course gets more difficult when these stories or feelings are amorphous or unruly or highly emotional.

But really, it’s when they are the most difficult that getting them on the page in a way that feels good and makes sense is the most cathartic and satisfying.

This memoir is your life’s story that you’re sharing with readers. But it also reads as a love letter to yourself, past and present. I say this because at times, you’ll switch from first to second person: readers are invited to connect with your story, while observing your older self connecting with your “inner child/teen,” so to speak. Why did you decide to incorporate second person in the storytelling?

I found that in that essay, I was using second person when talking about the central “exorcism” I underwent, first person when providing wider contextual information and then a more analytical voice when bringing in scenes from horror films.

An early reader of that piece pointed out that because the second-person voice was directed at my 12-year-old self, it felt to him like I was attempting to take care of my younger self, which I thought was an interesting interpretation.

So maybe in some ways, my younger self is who this collection was written for, or at least one person this collection was written for.

Religious trauma alongside toxic relationships with family are two big themes throughout the essays. I’ve heard some people say that going “no contact” is the last and final decision a child will make, after realizing nothing in the past has worked. I’m curious what your thoughts are on this familial discourse?

If going “no contact” is what you need for your own mental health, and if you can do that safely, then yes, do it. We owe our abusers nothing. The idea that the families we are born into all love us and will do their best by us simply because we are related by blood is a myth.

And romanticizing this myth often makes it emotionally difficult to leave and to heal. The sooner we are able to transcend this false narrative, the sooner we empower people to leave abusive or toxic family situations.

Making conscious choices about who our real families are (or are not) is empowering — not just for those navigating toxic family situations but also for those blessed with bio-families who are loving and supportive.

I mean, how beautiful to be able to honour your loving bio-family by being conscious of the fact that you choose them as family every day. So much better than taking that love for granted simply because they happen to be related to you.

That said, one thing I am always conscious about is the fact that not everybody has the ability to go no contact without compromising on their own physical safety — especially if you are young and/or financially dependent on your bio-family.

For queer communities, it’s important for us to find ways to support individuals who are in toxic situations and who are unable to leave. We also need to create safe and viable spaces for people to go to when they finally can. Leaving without having a place to land can be dangerous and devastating.

In a 2022 piece in the Atlantic, writer Mary Retta stated that queer and trans people “have long found camaraderie in horror.” You also write in your first essay that horror films reveal cultural anxieties. What does the horror genre offer queer and trans folks, even if the representation is one-dimensional or imperfect?

I agree that horror has a lot to offer queer and trans people. It also has a lot to offer women. I believe that several studies have found that horror is the only genre in which women appear and speak the same amount as men. And of course, women and queer folk are often treated like monsters in the real world. Our bodies are legislated, our intentions are vilified, and we are seen as “out of control.” When immersed in the fantasy world of film, why wouldn’t we be interested in monsters?

I often quip about how my love of horror films was a natural consequence of having lived one. I mean, my mother literally thought there were actual demons inside of me and a bunch of people literally thought they were getting them out of me — adults looked at me and thought I contained evil precisely because I was queer. Logically, it makes sense that I would love monsters — it’s how I learned to love myself.

But I think it is important to remember that queer and trans people are not a monolith. And that horror can be very divisive in terms of the reactions that it provokes.

For example, there are some people who have experienced traumatic incidents who may find viewing certain content onscreen upsetting or even triggering.

On the other hand, there are people who may have been through similar experiences who may find watching those same scenes cathartic, especially if the person onscreen experiencing that traumatic incident comes out victorious at the end of the film.

There is a lot of theory out there about why some people love horror — from pop-psychology pieces about how horror may actually strengthen some individuals’ capacities to deal with everyday challenges, to an essay I recently read in which a therapist talks about how she has clients for whom horror appears to offer a therapeutic vehicle for talking about trauma and processing it.

So I can’t tell you exactly what horror can offer queer and trans people as a whole, but I can tell you what it offers me as a queer person: horror has helped me process a lot of complex emotions and experiences.

The supernatural element of horror, precisely because it is not bound to everyday reality or rules, offers the possibility of repicturing big emotions and experiences like fear, rage, desire or grief in innovative ways that allow for the mess that these emotions sometimes contain.

It offers me a safe space to feel feelings that might be considered disruptive, disorderly, unmanageable.

Onscreen, grief may be a monster that lives in your house. Or trauma might be a ghost that haunts you. For me, certain horror films have a way of repackaging these experiences, and returning them to me in ways that allow me to articulate them.

Your half-sister Sky wrote to you, and one of the lines that stayed with you was “I hope you are happy.” How does that statement sit with you now?

What does it mean to be happy? I’ve lived through long periods of depression. Is being happy simply not being in that space anymore?

Happiness is fleeting. It is not something you can consistently feel. If you were consistently happy, the feeling would eventually be meaningless.

Rainer Maria Rilke said it well: no feeling is final. I’m less concerned about happiness these days and am more concerned about finding meaning in the things that I love and things that I do, and taking pleasure in them when I can. ![]()

Read more: Books, Rights + Justice, Gender + Sexuality, Film

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: