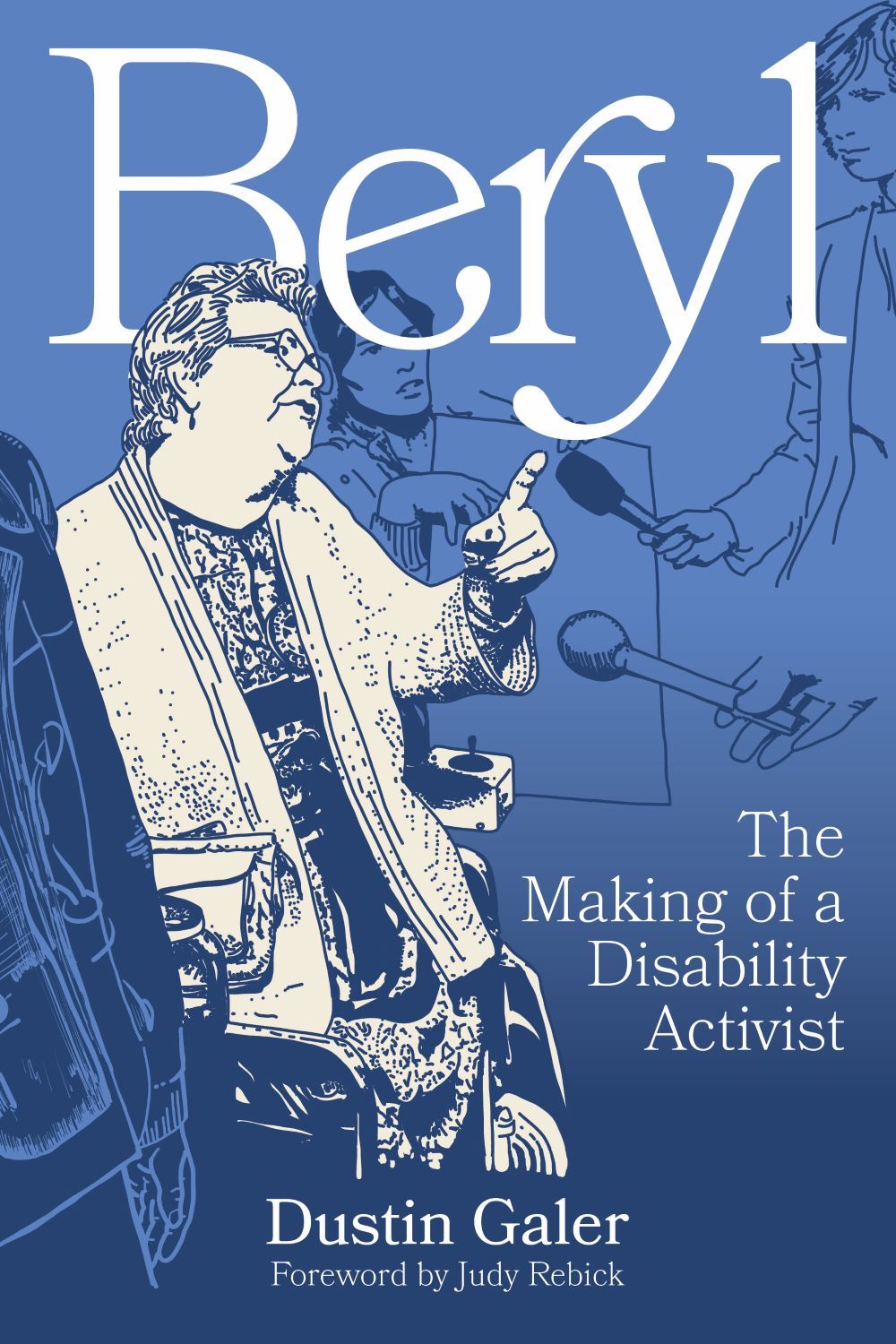

[Editor’s note: Dustin Galer’s in-depth, unflinching biography of Beryl Potter documents her impact on the world of disability justice in Canada. Below, we include additional context from Galer about Potter’s life and the context in which she was fighting:

After a simple slip and fall at the bakery where she worked as a new immigrant to Canada, Beryl Potter suffered complications, such as blood clots, that resulted in multiple amputations, an addiction to painkillers, and suicide attempts. She survived, and became one of the most recognizable disability activists in Canada. From the 1970s to the 1990s, Beryl regularly flashed across newspaper and television headlines, whether it was a protest she organized that shut down Yonge Street during rush hour or a major demonstration on Parliament Hill in Ottawa.

Her story diverges from typical tales of triumph over tragedy, the kind of stereotype-reinforcing inspirational fluff about disability or people with disabilities that often populates bookstore shelves. Beryl was a complicated person with a sometimes difficult personality and parts of her story are quite provocative and controversial, such as the time she grabbed the prime minister to secure a meeting with him, or the many times she defied government overseers who crossed her.

When she wasn’t lobbying or protesting, Beryl was in classrooms. Over the course of her career, she probably spoke to tens of thousands of students about disability issues. And I was one of them. I met Beryl briefly as a child when she visited my school, a faint impression that I rediscovered while writing this book. Beryl always said children are our future doctors, architects, political and business leaders; she felt strongly that if she were able to generate empathy in young minds to replace fear or ignorance, children would carry those impressions into their adult lives and various lines of work. For Beryl, this was the key to unlocking a generational shift in attitudes and practices that shape the lives of people with disabilities.

Unfortunately, most of the issues Beryl fought are just as relevant today. People with disabilities still face accessibility issues, problems with paratransit services and difficulty finding affordable housing, as well as widespread poverty, unemployment and discrimination. Beryl knew hers was a long-term project that would necessarily outlive her. As her story reaches a new generation, hope remains that she may one day achieve her goal with others carrying the torch forward. ]

Beryl Potter was especially bold whenever she dealt with transportation issues. She learned early on that building affordable and accessible transportation systems would be critical to the successful integration of people with disabilities.

“Before my accident, I took transportation for granted. I was completely mobile, and if I wanted to go shopping, I hopped in my car or took a bus. But for so many of the disabled, it just isn’t that easy. We have to be taken. We just can’t race off across town whenever we want to. If we have an appointment with a doctor, we have to book a ride several days in advance,” she said.

Transportation consistently topped Beryl’s list of activism priorities. It began with her fielding distressed calls from stranded people who missed paratransit rides. She knew from personal experience what it felt like to wait for hours for a ride that sometimes never showed up, the frustration and embarrassment, the desperation of digging into a limited monthly budget to shell out cash for an expensive accessible taxi.

She knew first-hand how the broken system of paratransit services undermined the ability of people with disabilities to make and keep appointments, to get a job and to participate in community activities and events.

Some employers who were open to hiring people with disabilities had their own reservations, as one such employer declared in a 1981 documentary. “One of the first questions we will ask a handicapped person when they apply for the job is their mode of transportation,” explained the employer. “It’s two strikes against him if he has to use Wheel-Trans.”

Ever since paratransit services were introduced by the Toronto Transit Commission in 1975, there were problems. All-Way Transportation, the private subcontractor for Wheel-Trans, was not up to the task of ferrying passengers to and from their destinations in a safe and timely manner.

The Wheel-Trans service was highly subsidized by the province and municipality, providing riders with disabilities with essential door-to-door service for the price of a standard TTC fare. In 1981, TTC fares were $0.57 or $29.75 for a monthly Metropass, allowing unlimited travel.

Many Wheel-Trans passengers carried Metropasses but were charged extra for non-subsidized evening rides, with some passengers racking up additional bills over $980 per year, nearly triple the rate of annual Metropass fares.

In September 1980, complaints of missed pickups and injuries on Wheel-Trans buses led Beryl to petition a local justice of the peace in Toronto. She charged that the TTC, All-Way Transportation and its owner Nick Comsa Sr. should be charged with criminal negligence.

The justice dismissed Beryl’s petition, but she sought an appeal, hoping to raise contributions from the community to cover legal fees. In November, a passenger named Lynne Pyke died while getting out of a Wheel-Trans bus. The tragic incident prompted the TTC to open an official inquest to determine the cause of Pyke’s death and any systemic shortcomings that required change. It was clear something was very wrong with paratransit in Toronto, and Beryl did her best to draw public attention to the problem while holding officials to account.

Reports also began to surface of disabled students forced to crawl to get into Wheel-Trans vehicles that lacked the capability to “kneel” (sink the entrance to the curb) or deploy a lower step.

Jill Cowie of the Iron Butterfly Parents’ Association alerted Toronto public school board trustees to a range of problems with All-Way: drivers caught smoking while driving, arriving late for the opening of school, refusing to help students on and off the bus despite contract language stipulating that “in necessary cases, the driver will be obliged to assist students to and from the vehicle or dwelling.” Despite these complaints, the Toronto school board lacked alternative paratransit options and renewed its $807,000 contract with All-Way to provide Wheel-Trans service to students with disabilities across the city.

As complaints about Wheel-Trans ballooned, Beryl organize to protest the TTC. She started by collecting signatures in a petition urging the TTC to cancel its private contract with All-Way and bring Wheel-Trans in-house to increase accountability, provide better public oversight and improve quality of service. The march would head north along Yonge Street to the Davisville headquarters of the TTC where the petition was to be presented to officials.

“I’m not a militant,” Beryl told a reporter. “I won’t be a militant until I start burning buses. Some people do not agree with me, but so far, the phone calls I have gotten from the people in distress who use Wheel-Trans support my actions.”

For her actions against the TTC, Beryl had been called a radical and a leftist activist, but she dismissed such labels. “All I am doing is simply taking a firm stand on the basic rights of the disabled.”

The line between passion and militancy was one that she would continually traverse. Her brother Norman remembered when her personality shifted following her accident. “In fact, I think she’s gone too much the other way,” he told an interviewer. “She’s too militant, and I’ve told her so. I hear her voice on the newscast and the timbre doesn’t sound like my sister. I tell her, ‘Tone down. If you get too enthused, you’re going to hurt the people you’re working for. You’ve got to know where to draw the line.’ But you know, I’ve still got the best damn respect for her.” Indeed, Norman was not the authority on how Beryl had evolved over the years, but he did have the longest perspective on how much she had changed since before her accident.

On the morning of June 25, 1981, trailed by a documentary film crew with cameras rolling, Beryl and a crowd of around 75 people using manual and electric wheelchairs, some with their personal care workers, met at Nathan Phillips Square in front of Toronto City Hall. Year of Disabled Persons flags were mounted high atop their wheelchairs and placards read “STOP using unsafe equipment!!” and “STOP injuring disabled!”

Beryl presided over the demonstration in a smart chiffon blouse and skirt, her purse pinned neatly to her armrest, as police arrived to escort the demonstrators along their route. Beryl deliberately chose rush hour to begin the demonstration to attract maximum attention by causing the biggest disruption along one of the busiest traffic corridors in Canada’s largest city.

Car horns honked relentlessly, either in support or perhaps out of aggravation, as Beryl delivered interviews to reporters on the fly.

“Naturally, yes, we need the special buses. Right? But I would like to see total accessibility. Our suggestions did not seem to be getting us anywhere, so ultimately, we were forced to bring them before the public.”

The Toronto Star reported that Wheel-Trans was allegedly responsible for lost jobs, missed appointments and injured passengers.

Later, Beryl reflected on the demonstration with a devilish sense of pride. “It was quite a sight. All those people in wheelchairs, motorized chairs as well as manual ones all making their way up the main street of the city. Why in the middle of the street? Well, we simply could not get our wheelchairs on and off the sidewalk.”

On their arrival at TTC headquarters, they were met by TTC officials who invited Beryl into the building to discuss their proposals. Scarborough Controller Joyce Trimmer, who also marched alongside demonstrators, joined Beryl in the meeting. Born in London, England, Trimmer immigrated to Toronto around the same time as Beryl and had been involved in politics since the early 1970s, and in 1988 was the first female to become mayor of Scarborough.

Beryl, Trimmer, another politician and a few other Wheel-Trans users met with TTC director of operations Lloyd Berney and other board members for over two hours. Some riders gave personal accounts of their experiences, including missed and late pickups, poor scheduling, poor customer service and inadequate levels of service to meet demand.

Beryl shared some of her own experiences riding Wheel-Trans. “The bus arrived 15 minutes early. I’m on the 14th floor, and by the time I got down there, the bus had left. I came up, and I phoned them and said, ‘You were not there. I see you are 15 minutes early.’ They said, ‘Well, that’s not our fault.’ ‘Are you coming back for me?’ I asked. ‘No, forget it,’ they said.” These were just a handful of experiences that she argued pointed to larger systemic problems with Wheel-Trans operations.

The meeting was universally seen as a constructive exchange. Beryl convinced Berney to come down and address the demonstrators himself. They were greeted by a round of applause in the packed lobby as people stood shoulder to shoulder and wheelchair to wheelchair to hear what had been discussed.

“I think I was on the receiving end more than I was on the giving end,” Berney admitted. “We’ve heard the concerns of the group that came up here on this protest march today.... I’ve also indicated to your people that we will be taking a good look and that I will be recommending in September that the commission give consideration to taking over this service at the expiry date of the contract.”

The announcement appeared to be a significant commitment to change. But as Beryl would repeatedly learn, verbal commitments did not always translate into meaningful action. Despite Berney’s decisive words in front of the demonstrators, the TTC renewed its contract with All-Way, and problems with Wheel-Trans persisted throughout the 1980s. It would not be the last time Beryl would confront the TTC on the streets or behind closed doors, but each time her trust was betrayed by a politician or bureaucrat, she found herself more and more on the militant side of the line, a little more obstinate and a little less compromising.

Excerpted from ‘Beryl: The Making of a Disability Activist’ by Dustin Galer. Copyright 2023 Dustin Galer. Published by Between the Lines. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.

Happy holidays, readers. Our comment threads will be closed until Jan. 2 to give our moderators a much-deserved break. See you in 2024! ![]()

Read more: Books, Rights + Justice, Transportation