One day while I was working in The Tyee office, the phone rang. When I picked it up, a booming voice came through the receiver. “Dorothy, it’s Max Wyman!” I was more than a little startled for two reasons: in cultural circles, Max Wyman is a big deal. And secondly, had I done something to piss him off? Thankfully, no. He was calling to let me know I’d won the Max Wyman Award for Critical Writing. It came at funny time, March 2020, just as the pandemic was closing down the world. At The Tyee, we packed up our things and went home, uncertain of when we would return or what would happen in the next while.

I remember that period as a deeply curious one. It was terrifying but also strangely fascinating. All of a sudden, the world was stilled. No shopping, no commute, no office chatter. I checked the COVID infection rates counter every day, watching it shoot straight upwards in a perpendicular line.

In this period of suspended animation, the thing that provided the deepest and most profound comfort was the arts: films, books, music. It didn’t matter if it was a cheesy action movie or a grand opera streamed from one of the preeminent venues in the world: culture filled the sudden chasm previously occupied by everyday existence. Like everyone else, I took from it what I needed to see me through the darkest and most challenging of times.

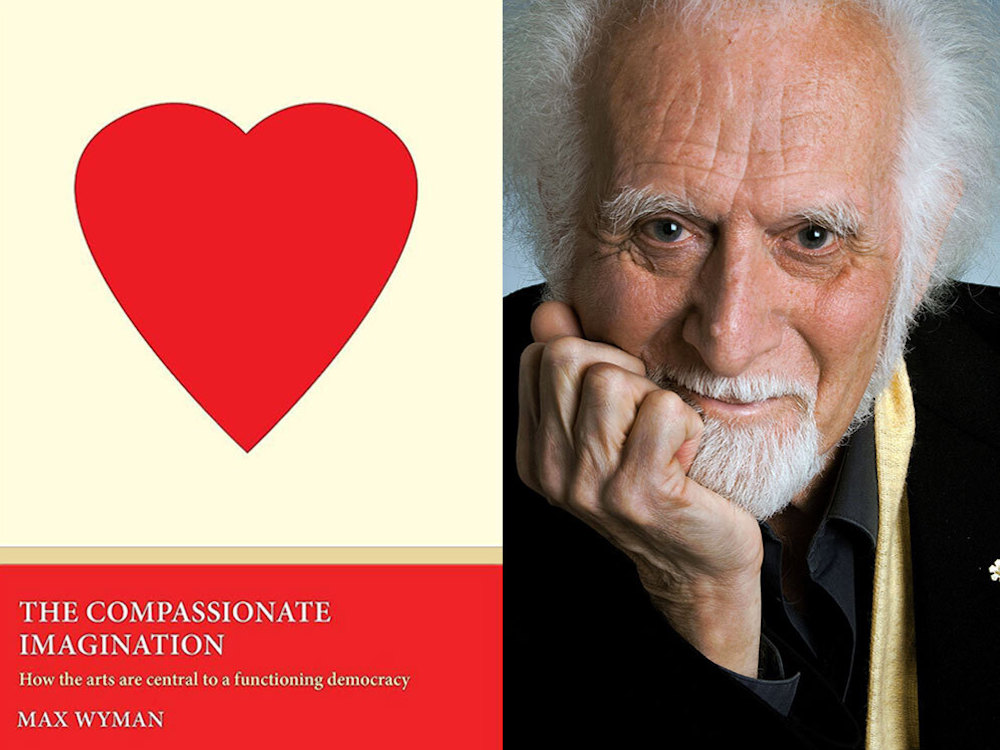

I still think a lot about what culture meant during that period, and a great many of my thoughts I see echoed and articulated (in infinitely better fashion) in Max Wyman’s new book The Compassionate Imagination: How the Arts Are Central to a Functioning Democracy.

After writing about culture and the arts for more than 30 years, Max Wyman is a living library of information, ideas, analysis and wisdom. He started his journalism career in England before moving to Canada in 1967. As the dance, music and drama critic for the Vancouver Sun and CBC, he helped shape the cultural community in Vancouver. His latest book is an impassioned manifesto about the critical importance of culture and a celebration of the very best things us humans are capable of.

The Max Wyman Award certificate sits on my desk, a benevolent reminder to keep working, to keep fighting for the critical importance of the arts. Critical is the important part. As legacy media continues to dwindle, sometimes it’s arts and cultural coverage that are the first things to be cut.

But as Wyman’s book makes abundantly clear, the arts might just be our saving grace. Whether it’s dance, opera, books or painting, the act of creating and sharing with other people is the most direct and impactful way to foster empathy, understanding, appreciation of this thing we call existence, as Max demonstrates in his inimitable fashion. They ennoble us difficult, cantankerous, intractable humans.

Ennoble isn’t a word you hear very often anymore, but it speaks to the innate dignity and need for beauty, truth and goodness that exists in all of us. I am very proud to ask Max a few questions about his work.

The Tyee: In your introduction to The Compassionate Imagination, you write about the capacity of the arts to “reawaken our sense of decency and empathy toward one another and to regenerate a sense of common purpose in our increasingly splintered existence.”

I keep thinking about James Baldwin’s quote: “Wherever human beings are, we at least have a chance, because we’re not only disasters, we’re also miracles.” Although we certainly seem more disastrous than miraculous at the moment. Whether it’s folk fighting about Sesame Street or Barbie, culture wars seem to be where a great many of the current social struggles are taking place. Given the volatility of how people react to culture, do you feel that collectivity and consensus are still possible?

Max Wyman: I do, of course I do, or I wouldn’t have written this book. A friend often chides me for spending my life — as he puts it — tilting at windmills, and points to this book as another example. I’m asking for a radical restructuring of society, after all, with the arts and culture given the same importance as health and education and all the other things we believe are essential to a thriving democracy — not separate from them but interwoven with them... reinfusing our social discourse with the decency, openness, modesty, goodwill and yes, compassion, that have been markers of the Canadian character.

My friend is not alone in his skepticism. I prefer to think of myself as a pragmatic optimist. Of course I recognize the scope of the challenge. Institutions need to be reshaped. Inequities demand remediation. Justice systems must be recalibrated. But I feel, as many others do — important among them the philosopher Martha Nussbaum — that compassion is a necessary component of a properly lived social life, and I believe that the arts are ideal tools to help us learn it and be shaped by it.

When we experience the emotions or experiences of “the other” by living them vicariously through stories and plays and pictures, or by sharing and exchanging the products of our imaginations, we understand each other better as human individuals. We get a clearer and better idea — a more just and humane idea — of how we might go about fixing our confused and fractured world. Being compassionate means taking a chance on trust.

When I summarize it like that, it would be easy, probably, to interpret this book as some kind of utopian dream of everlasting social harmony. It’s not at all that. Utopia is an illusion. As Tom Stoppard puts it in one of his plays, “there is no such place... we have no consolation to count on but art and the summer lightning of personal happiness.”

Yes, I envisage a revolution of sorts. But I don’t want the outcome of this revolution to be the sameness that’s implied by the word “collectivity”— quite the opposite. The world is filled with eight billion life experiences, every one of them unique. Instead of the endless competition and sniping that goes on in the world around us, how much better it surely would be if we had what Stoppard calls “a contest of generosity… empathy, patience, kindness, action, communication — followed by more of the same.”

So, my book doesn’t map a new and glorious Canada. All it does is try to imagine a set of circumstances that will allow us to speak to each other, as we should, with respect and trust and openness — through art, in the summer lightning of personal happiness.

This sense of fragmentation, coupled with the changing nature of the media landscape, especially in the last few years, has not been kind to cultural criticism. As legacy media continues to dwindle and new forms of engagement arise, be it TikTok or Instagram, how do you see the arts changing as people find new ways to access information, be it reviews or more in-depth coverage?

Inevitably, the internet has affected the critic’s role. The job I did for much of my life, arts criticism, has been rendered — is thought to have been rendered — redundant by the ability for everyone to circulate their views, instantly, to the world, in 280 characters, reductionist thinking in a virtual nutshell. This is clearly reflected in the diminished attention given to arts criticism by all the major traditional outlets. It doesn’t get the eyeballs and the clicks that justify in economic terms the real estate it used to occupy.

What we’re seeing is a steady gravitation to specialist online cultural journalism. The big problem of course, is how you monetize that.

The changes in the arts themselves are always going to happen: that’s what keeps critics on their toes.... No sooner do you think you’ve got a handle on what is happening than off the artform goes, being something else. Classification into genres is not only out-of-date but has diminishing relevance. Everything is accessible, and everything is endlessly cross-referential.

The great and exciting challenge of writing cultural commentary today lies in finding ways to get a grip on that seething complexity, and new ways to write about it that will interest and provoke audiences, both the established and the new. However the form evolves, though, I believe we will need people who will stimulate critical thinking and enhance public understanding and appreciation of creative inquiry, even skepticism, in our interpretation of the world around us. This is not so much the era of the death of criticism as the period of its rebirth.

In the midst of the pandemic, the arts played a critical role, whether it was film, music, books or streamed live events. A lot of expectations are heaped on the arts to help humanity through its darkest moments. How do you envision culture helping people contend with the most challenging aspects of the coming (perhaps even grimmer) future?

It comes down in the end to the way art lets us recognize our shared humanity: fosters kindness, a process I’ve gradually come to understand and value the older I get. We should make it easier for people to be vulnerable — or, rather, to show their vulnerability without being afraid. Artists do that all the time; they lay themselves on the line and trust in the kindness of the rest of us. We don’t always oblige. Recognizing our shared humanity is sometimes a difficult trick, I agree.

How do we nurture compassion in such a corrupted world? Is there a place where the human spirit can find redemption and refreshment? How do we maintain a sense of wonder?

We do it by bringing art and culture to the centre of our lives — personally and together. I’ve had the good fortune to spend much of my life being paid to write about the products of other people’s creativity: music, books, theatre, art, dance, film and so on. And I know the experience has made me a better person than I might otherwise have become. Art helps us develop kindness, because it gives us glimpses of the way other human beings, creatures as vulnerable as ourselves, think and feel. It puts us back in touch with the empathy, decency and care I believe we were born with.

Watch a play, read a book, wander round an art gallery: you come away changed, even if it’s in the slightest of ways. You’ve seen a fragment of the world, or of a life, through someone else’s eyes. Culture is the great humanizer: an essential part of a healthy society. But it has always been short-changed by our governments, treated as a frill, something to be fobbed off with the scraps after everything else it taken care of. We live in a society in which we value everything in terms of what it can contribute to the economy. But you can’t show the value of art on a cost-benefit graph.

Your argument is that the arts are a critical part of a functioning and, arguably, healthy democracy. With the end of capitalism, the rise of AI, it feels like we’re in the midst of a major paradigm shift, a crossroads moment, if you will. Do you think this level of escalating crisis could offer something of an opportunity for seismic, systemic change?

The escalating crisis you describe — plus the pandemic, and an old-fashioned tanks-and-artillery war in Europe (in the 21st century!)... the ground we all stand on is trembling. If we’re not willing to make change now, I asked myself, when will we be?

You can’t ignore the headlines, but I sense a readiness, a positivity. There’s another world behind the flickering images on the walls of the cave, a world of people of goodwill yearning to move together in a better direction. And I do feel that this broad social movement for cultural change is at an inflection point — there's a real possibility of a transition from talk to action if a true popular movement — across society at large and not just the cultural sector — can be activated.

My concern is that we adjust so quickly. I even worry that we might already have passed the ideal moment: people are settling back into their old ways and old habits. So, it becomes more than ever important that we get these changes — and they are necessary changes in my view — started now.

This book is meant as a contribution to that process. It makes what some might see as pretty radical proposals, but it’s very much intended as a jumping-off point for debate, rather than a finished blueprint for change. I don’t pretend to know all the answers — but I do hope to provoke people into asking the necessary questions.

When I was reading your book, I kept thinking about all these different, brilliant folks like filmmaker Adam Curtis, designer Bruce Mau, anthropologist David Graeber, essayist Rebecca Solnit all calling out that another way of being is immediately in front of us, and that we desperately need to take it. Why does it still seem so hard?

It still seems so hard because it is so hard. Yes, “another way of being” is immediately in front of us, and yes, we desperately need to take it. But the political and social will to make such fundamental change to the ways we live together — change that will involve radical readjustment of the neoliberal capitalist system to which we are currently subjugated — is hard to rally when the forces devoted to preserving the neoliberal capitalist status quo (greed, self-interest, privilege) are so entrenched. On top of which, there’s the purely personal challenges that more and more of us are facing: paying the mortgage, putting food on the table.

But as Crawford Kilian observed on this platform, summing up the arguments in The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity, by David Graeber and David Wengrow, “we’ve walked away from bad societies for tens of thousands of years, or just said no, and then built better societies after long debate.” And as you yourself quoted Graeber in another piece, “The ultimate hidden truth of the world is that it is something we make and could just as easily make differently.” He’s right, of course.

What I’m offering in this book — opening up for discussion, not laying down as law — is a sketch of a framework for a new and better way to approach our future together. I think that’s something people are at least ready to think about. To spend our lives learning and feeling without being afraid of one another seems to me a fine ambition. You may say I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one. I hope.

While reading your book, I thought about Ursula K. Le Guin’s statement about the power of imagination: “The daily routine of most adults is so heavy and artificial that we are closed off to much of the world. We have to do this in order to get our work done. I think one purpose of art is to get us out of those routines. When we hear music or poetry or stories, the world opens up again. We’re drawn in — or out — and the windows of our perception are cleansed, as William Blake said.”

In your own life, what works of art cleanse your windows of perception?

Depends on the mood and the day, but I do need to have my heart pierced rather than my head made to admire, which ties in with that famous quote from Rumi: “the eye of the heart” is 70-fold more seeing than the “sensible eyes” of the intellect.

Dance is my first choice; I’ll probably never get tired of being overcome by the wordless meaning and emotion that moving bodies can convey. Lots of music can clean my windows of perception — if I started to name names I’d be belittling the ones I omitted — and I love a good wallow in a gallery, ancient or modern. Writing is a special area — I always gravitate to people I can envy for their style and elegance… and can love for their compassion. It’s a never-ending adventure and a never-ending feast.

Join The Tyee’s culture editor Dorothy Woodend in conversation with Max Wyman to celebrate the launch of ‘The Compassionate Imagination’ at Upstart & Crow bookstore on Granville Island, Vancouver on Sept. 24 from 6 to 8 p.m. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: