On the July weekend of the big family reunion, Chinatown is crowded with Yips.

It has been 142 years since Yip Sang, their towering ancestor, came to Canada and made his fortune; 134 years since he set up shop on Pender Street, where he would house three of his four living wives and their 23 children; 96 years since his death, commemorated with the longest funeral procession Vancouver had ever seen; 22 years since the family property was sold; and 15 years since this many descendants have gathered together for a reunion.

Yip Sang, who they affectionately call the “Grand Old Man,” was a community leader and savvy businessman with a sprawling network of enterprises in labour contracting, real estate, steamship travel, overseas banking, imports and exports, fishing and canning, and restaurants and catering — all at a time when Chinese people were increasingly stripped of rights by a racist government.

The family, one of Vancouver’s oldest, is now in its seventh generation.

“It’s very likely that you can pass a cousin on the street and not know,” says Linda Yip, one of Yip Sang’s great-grandchildren.

Together, the generations have experienced every period of the country’s history as Chinese Canadians: the railway, the exclusion era, the wartime years, the subsequent fights for rights and acceptance, and the 1967 policy that kicked off the country’s immigration boom, which would’ve been unthinkable to Yips who remembered a time when they were denied citizenship despite being Canadian-born.

Reunions of this grand scale only happen every dozen years or so. This one took months of emails, phone calls and in-person invitations for seniors who don’t use either, preferring someone to knock on their door to tell them there’s a party.

The family has taken over the Chinese Cultural Centre for the weekend, packed with great-great uncles, great-grand nieces, cousins many times removed and relatives from another mother. While there are Yip descendants still in the Vancouver region, some have flown in from across Canada and across the world to attend the reunion, with wide-ranging careers in places like Hollywood and the United Nations.

With almost 400 family members in attendance, there’s the air of a conference. In between the hugs and chatter, there are lectures on family history in the auditorium. There are silent auctions for everything from cognac to family cookbooks. There’s a seemingly unlimitedly supply of buns coming from the kitchen. There’s a 50-50 draw, and just about everyone who runs into Auntie Grace is persuaded to buy a few.

Grace, who everyone calls auntie, and her husband Hoy Yip have been called the “keepers of the flame.” For years, they had a bedroom in their Vancouver home dedicated to Yip family records. They’ve been helping reunite the Yips ever since the last of the families moved out of the Chinatown home.

“This is the sixth reunion: 1972, 1986, 1989, 1996, 2008 and this one,” says Grace, who rattled them off like Olympic years.

On the wall is the Yip family tree, with 974 descendants on its many branches. Old Romanizations of Chinese surnames like Chew, Der, Gim and Soon are a testament to just how long the family has been in Canada.

“We wrote the first one by hand,” says Grace. It helped that her husband was an electrical engineer with experience drafting and that they had a neighbour willing to handle the Chinese names.

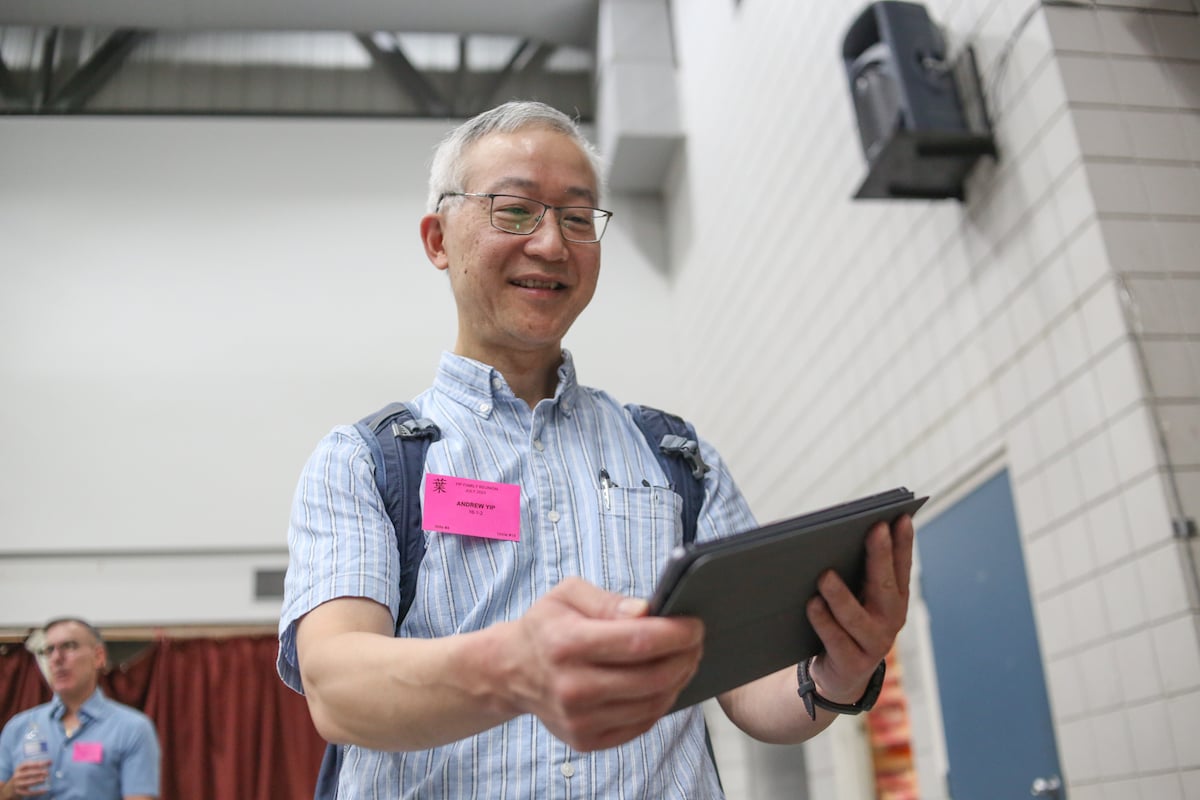

But now, it’s done in AutoCAD, a program used by architects to design buildings. Andrew Yip, a great-grandchild, took up the responsibility. As it is with families, he says he first started helping out when “Auntie Grace just called me.”

“You did a magnificent job! Sorry if I bugged you so many times,” says Auntie Grace, who snuck in her grandson’s Chinese name 10 days ago, just in time before the family submitted their order of trees from a large-format print shop.

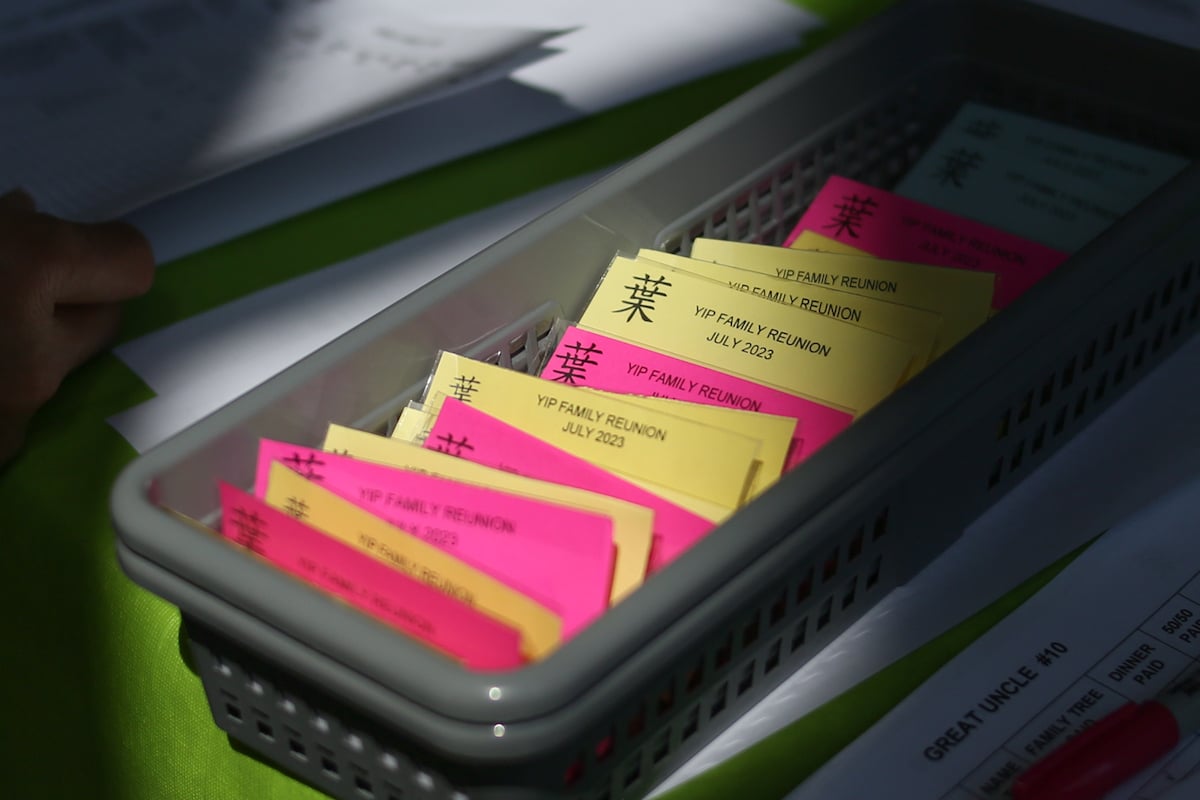

While the tree has been neatly designed, it’s still a dizzying document. To help everyone make sense of who’s who, there are detailed nametags at the reunion.

Each person’s is colour-coded by generation and identifies which of the four wives and which of the 23 children they’re descended from. Each person also has an identification number, a shorthand for their lineage that shows where they fall on the family tree.

Linda is 911, which means that she’s descended from Yip Sang’s ninth son and two subsequent firstborns. As a professional genealogist who’s become the go-to source for family history, she couldn’t have been designated a better number.

“It’s perfect because it’s so memorable,” she says. “If anyone wants to know anything about genealogy, just dial 911.”

Family trees tend to be patrilineal; Yip Sang’s all the more so with the heavy emphasis on sons, of which he had 19. But Linda is dedicated to ensuring that male biases don’t exclude the stories of women who married out of or into the family. There is important history in her own immediate family through her mother, who is descended from Chinese farmers who were tenants on Musqueam land.

The reunion will conclude with a dinner at the Floata Seafood Restaurant, where the Yips have booked 38 tables. The photographer for the day can’t help but quip, “Who’s buying?”

But before dinner, there’s something special planned for the afternoon: a tour of the Wing Sang, the family home and place of business on Pender Street, which has just been renovated by its newest owner. The name of the building means “Everlasting” in Chinese.

Just last year, real estate marketer Bob Rennie sold the building to the Chinese Canadian Museum, which had been eyeing the property for its permanent home.

The museum transformed Yip Sang’s compound of a residence and bustling place of business into a place for the public to learn about the Chinese diaspora. Parts of the building have been restored to look like it did when the Grand Old Man was around, down to the wallpaper and furniture.

The first of the family to step through the doors of the Wing Sang are Yip Sang’s grandchildren, who grew up in the building and remember rollerskating down its many halls, and when relatives would come in for tea ceremonies on their wedding days.

Five decades since anyone from the family has lived in the building, the Yips are in the house again.

The Grand Old Man

The younger generations farther removed from Yip Sang and the family’s Chinatown days are learning a lot this weekend, like 13-year-old Ella Kennedy, who’s been meeting her cousins from all over the world.

She was surprised to find out from her mother that she was one of Yip Sang’s great-great-great-grandchildren when doing a school project.

Her conclusion of his life and times: “The guy had layers!”

The stories about Yip Sang’s life have layers too. It can be hard to separate fact from fiction after years of tales grown in the telling by everyone from biographers, journalists and even family members. For example, that Yip Sang had a wealthy grandfather and that he came from a fruit-growing district, neither of which is true.

Another oft-repeated detail is that Yip Sang was an orphan, which some family members at the reunion realize could not have been true upon seeing that the brother who eventually joined him in Canada was eight years his junior.

“I’ve been told that story so many times,” says Linda. “I know we’re trying to fill in the details. People may make up the story, but I love that we have these fables of where Yip Sang came from.”

History does make it clear that Yip Sang never struck actual gold.

In 1845, he was born in Taishan, Guangdong as Yip Loy Jiu. Like 25,000 other Chinese migrants, he was drawn to the promise of “Gold Mountain” in California. So at age 19, he left home to try his luck.

In San Francisco, Yip made some money not in the goldfields, but as a cook, cigar roller and dishwasher. In 1881, he picked a different destination further up the coast: British Columbia. Again, no gold. Instead, he sold coal door to door.

His work ethic caught the attention of a labour contractor, and Yip was hired to help manage migrant workers on the Canadian Pacific Railway. He worked many jobs and was responsible for paying thousands. It is said that he rode a horse between campsites with a bag of money and a gun.

Over the years, Yip made a few trips back to Taishan. It was common for prominent men to be part of multiple, simultaneous marriages to father children. At the suggestion of his first wife, he married a second and third to help with a growing household. In 1885, when the coast-to-coast railroad was completed, he once again returned to Taishan. His first wife died around this time and he married a fourth.

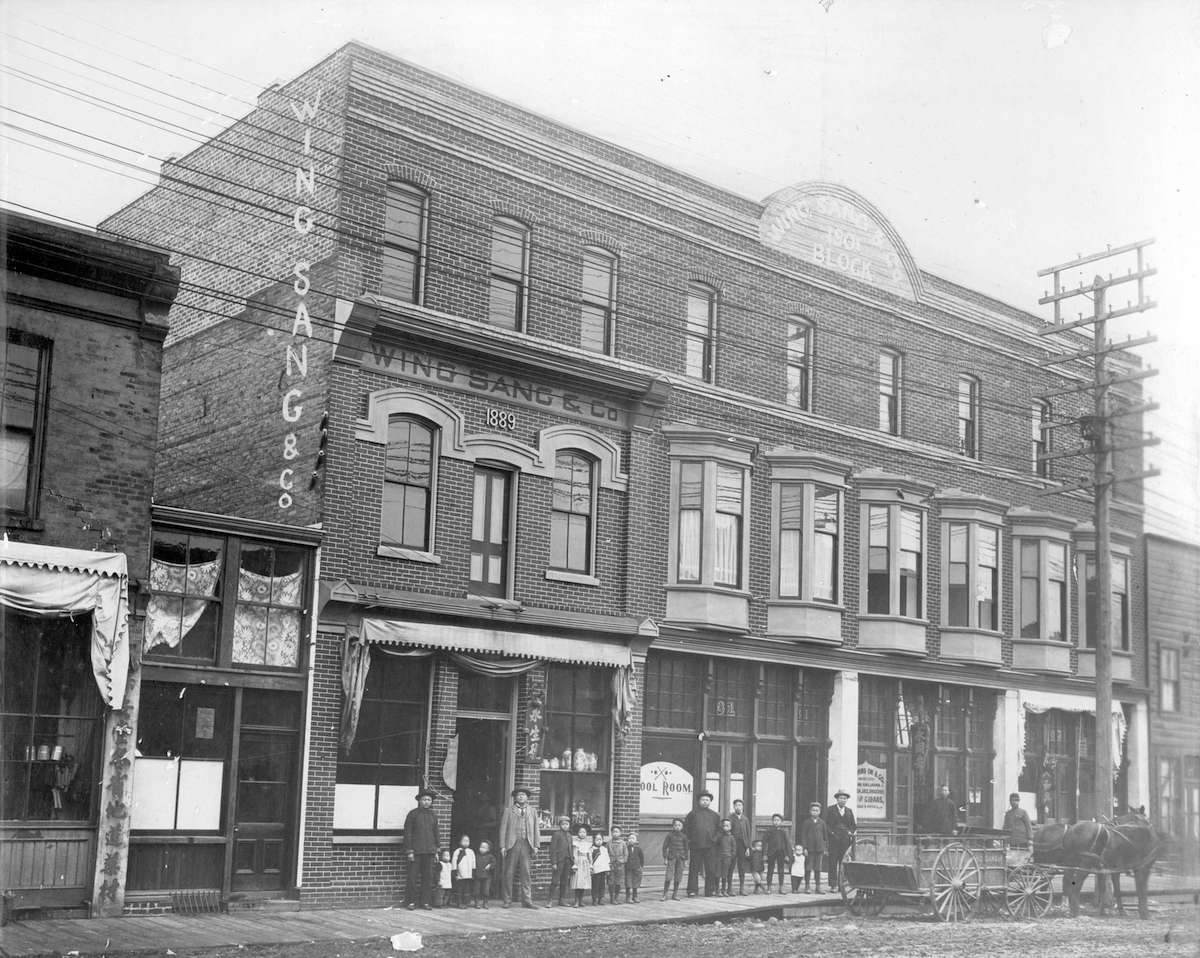

At age 44 in 1888, Yip returned to Vancouver and founded the Wing Sang Co. on Pender Street. His businesses would touch virtually every aspect of the lives of the Chinese diaspora, whose rights were continually eroded with racist legislation by a government that didn’t want them in the country. To match the name of his company, he styled himself “Yip Sang.”

It took nearly two decades for all of Yip Sang’s own family at the time — three wives, four children and a daughter-in-law — to join him in Canada, due to tightening rules and new fees for arrivals from China, a hint of the migration ban to come.

Yip Sang made his fortune as the Wing Sang became the place to shop, find work, borrow and transfer money, and pick up mail. Canada Post, then called Royal Mail Canada, would dump letters they couldn't read in Chinese at Yip Sang’s business.

As a sign of his wealth and holdings by 1904, Yip Sang contracted a Victoria builder to make $50,000 worth of brick for what the Victoria Daily Colonist called a “village of buildings” in Chinatown, equivalent to about $1.4 million today. He owned 26 properties in Vancouver at the time and would add four more in Burnaby and New Westminster.

In 1912, Yip Sang built a six-storey residence immediately behind and connected to his place of business on Pender Street for his family. His three living wives, with their respective children, each had a floor of their own. They were known by their maiden names of Dong, Wong and Chin, but everyone called them the First, Second and Third Lady.

Beyond his businesses, Yip Sang was also politically active and a community-minded philanthropist, helping establish the Chinese Empire Reform Association, the Chinese Benevolent Association, the Chinese School and the Chinese Hospital, which later became Mount Saint Joseph Hospital.

Education and health care were especially crucial at a time when the diaspora in Canada experienced exclusion. Yip Sang also donated money for schools and hospitals in Guangdong.

He was known as Chinatown’s unofficial mayor and was even questioned by prime minister Mackenzie King about the anti-Asian rioters that swept through the neighbourhood in 1907. A transcript of the exchange shows Yip Sang’s prowess in English as he lists his extensive assets.

But even a man of his stature was not invincible, says Linda. At best, Yip Sang was “tolerated” by the white establishment. She found records that he was held for four days in Victoria’s Chinese Detention Shed in 1914, an extension of ports for Chinese people without proper documentation. Ironically, the detention sheds were a customer of Yip Sang’s, who provided them with catering.

In 1925, the Grand Old Man had a grand old party for his 80th birthday. He hosted festivities across Chinatown, with 1,200 dinner guests across eight restaurants. It was a larger affair than the 2023 Yip family reunion.

In 1927, Yip Sang died at 81 years old from complications resulting from an old gastric ulcer. At a time when others from China sent their bones overseas, he was buried in Vancouver’s Mountain View Cemetery, cementing his place in Canada.

So what happened to all the money?

“I’ve been asked that several times and I’m curious myself,” says Linda. “To people outside the walls of Wing Sang, he was fabulously wealthy.”

Linda has a few theories. When the Chinese Exclusion Act came into effect, officially known as the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923, she believes that the import and export business was hit by a reduction in the number of ships coming into port. The travel and immigration business would also have been hit due to tightening borders, which were essentially closed.

“I think the Yips were used to a fancy, high falutin’ way of life,” she says. “For example, their assumption that they could travel back and forth to Hong Kong, visit family and party, to get wives — all of that was expensive. I have pictures from the 1910s. There’s one in 1917 where everyone’s in lace, they’re having garden parties.”

What money that was left would’ve been divided into many portions between the 18 out of 19 living sons and trustees of his businesses. While many of them were successful, none of them ascended to the status of Yip Sang.

“I don’t think it takes very long before all that dissipates,” says Linda.

House of the Yips

The grand Victorian exterior of the Wing Sang looks as good as it did in Yip Sang’s day as his descendants step through the front doors.

The inside, however, is a bit disorienting to those who grew up within its handsome brick walls. Mel, one of Yip Sang’s grandsons, lived here for 15 years. Back in 2008, Bob Rennie invited the Yips during their last reunion to see how the space for his real estate offices and gallery was coming along.

“Where am I?” Mel had said. “Which way is Pender Street?”

The last of the Yips to live in the Wing Sang moved out of the residential wing in the mid-1970s.

While the business wing was in relatively good shape — having housed gift shops, a seafood restaurant and the insurance offices of Gibb W. Yip over the years — the residential wing had been condemned due to rainwater soaking through the timber framing.

In 1989, the family invited the city archives to recover materials of interest inside the building. Many of the documents were wet and mouldy, with the surviving materials fumigated and freeze dried.

When Rennie purchased the building in 2004, it took workers in hazmat suits two months to clear the muck of used syringes, dead pigeons and a foot-high layer of droppings.

The floors of the residential wing that had been divided between Yip Sang’s wives and their children had to be taken out as a result. Rennie turned it into a cavernous gallery, but kept the brick wall, reinforced with shotcrete.

Looking up at the 40-foot ceiling of what is now the main gallery of the Chinese Canadian Museum, Mel, now 88, points to the airspace near the top where his bedroom once was.

“I lived on the sixth floor,” says Mel, who is descended from Yip Sang’s eighth son and shared the floor with the families of sons four, six and 12. “Can you imagine four families on one floor, sharing one kitchen, two toilets and one bathroom? We made it work.”

Rosalie Yip, age 93 and the oldest in the family today, also lived on the sixth floor with Mel.

“There were long stairs but we got used to it,” she says. “We used to play in the staircases and slide down in potato sacks.”

Many of the children who grew up in the Wing Sang had fond memories of games in the warren-like compound: hide and seek, football, zipping down the hallways in roller skates and shooting hoops on the open-air deck on the third floor. The adults too enjoyed the companionship. Anytime someone wanted to play mahjong, it was easy to find three others.

Mel also admits that life in Wing Sang, home to almost 100 people, could’ve been overwhelming for spouses who married into the Yip family, like his mother.

“My dad went to Hong Kong and married my mother in 1921,” he says. “Can you imagine the cultural shock of not only leaving your family but moving into a strange country? Moving in with one father-in-law, that’s normal. But three mothers-in-law? And all the brothers-in-law, sisters-in-law, cousins, nephews, nieces?”

As the Yip family tour the building, they pass a screening of a museum-produced documentary on Yip Sang and his descendants, where the seated tourists are unaware that the real deal is passing beside them.

There is one room that was remarkably intact by the time Rennie moved in: the classroom. It is on the third floor of Wing Sang’s business wing and was the home of the Vancouver Independent Chinese School. There are two green chalkboards at the front of the room, which Rennie put behind glass to preserve the writing of Yips from decades past.

Rosalie the eldest never attended this school, educated at the local public school instead, but she remembers that the classroom was converted to house the ancestral shrine. When a Yip got married, this was where the family would host the traditional tea ceremony.

Beside the classroom is a painstaking recreation of the Yips’ living room, with pink floral wallpaper and cultured pleasures like a piano and a phonograph. The museum researched what it would’ve been like with help from the family and old photographs, recovering furniture from auctions.

On the walls are images of the Yips at celebrations. There’s a wedding, a Christmas party, a day out boating and a portrait of the Chinese Students’ Athletic Association upon their 1933 victory of the Mainland Cup, with family members making up half the team. Each is packed to the edges of the frame with faces.

The finery and the sheer size of the family are evidence of what an anomaly the Yips were during Canada’s early years, when lonely bachelors could only dream of being united with their loved ones on the other side of the world.

Children of exclusion

In the museum’s documentary on the family, Yip Sang’s grandchild Audrey talks about the fun and freedoms within the Wing Sang’s walls, but also the isolation.

“My mom did not allow us to go outside because it’s not safe,” she said. “In a way, she was protecting us.”

As much as the Wing Sang was a warm home, it was also a fortress.

Cecil Yip, Linda’s late father, also grew up in the building. He was born in 1922, one year before the “Chinese Exclusion Act,” meaning that he lived with the weight of the racist legislation during the formative years of his life.

Cecil didn’t like to talk about the Chinese identification card that identified him as a non-citizen, not even when Linda found it in a drawer. He didn’t like to talk about the Second World War, not even when Linda asked him what it was like to be a veteran.

“If he did say something, it was, ‘I don’t want to talk about it,’” says Linda, whose curiosity about those early decades of history as experienced by her family led her to become a genealogist.

But one of the rare things his father did tell her was, “You had to be tough to grow up in Chinatown. And if you stepped outside, you’d get beat.”

Cecil naturally loved soccer. With so many cousins in the house, the team was ready-made. He too played on the Chinese Students’ team. While the team’s victories were a mark of Chinese pride during the exclusion era, they were hard-won against white teams and white referees.

“It was hardcore and rough,” says Linda. “Not only did you have to be better, faster and more fleet-of-foot than all of your other competitors, they literally got into fights while they were waiting on the sidelines to play.”

Rules would be skewed, and during a match in Victoria the team was charged a $10 fee per player.

“That generation, my parents’ generation, there is some aspect of self-loathing in it because they absolutely internalized racism,” says Linda.

“When you’re bullied at school, what happens? Do you hate the people who go after you? Maybe. But you also hate all the things about you that they pick on. Look at assimilation. That’s not being proud of who you are. That’s trying not to stick out because you’ve learned that when you stand out, it attracts negative attention.”

Homecoming

At the Yip reunion, everyone is congregating around the family tree to see how they’re all related.

The Grand Old Man, of course, is at the very top, followed by the four wives and the 23 children beneath them.

Kew Dock Yip, one of Yip Sang’s sons, became the first Chinese Canadian lawyer and fought for the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Kew Ghim Yip, another son, became the first Chinese Canadian doctor to practice western medicine. Once a week, he worked at a free clinic at Main and Hastings for pensioners and others who could not afford private medical care.

Susanne Yip, one of the four daughters, received university education at McGill and Columbia, where she completed two degrees in three years in the 1910s. She taught in Vancouver and Guangzhou, where she was a headmaster.

“We do tend to think a lot about Yip Sang,” says Linda. “But if you think about this legacy in terms of descendants… you can see the flowering of so many social needs that the community required but didn’t have.”

As more Yips got educated and got married, they left the walls of the building. But the end of the exclusion era did not mean an end to racism.

“Some areas were friendlier than others,” says Ava Lee, a great-great-grandchild of Yip Sang, descended from his firstborn.

In the 1950s, her parents moved to a house at Cambie and 27th, the second Chinese family to call that part of Vancouver home. Not long after, a white man approached her father.

“He asked him to sign a petition saying no more Chinese people in the neighbourhood. Let’s just say my father gave that person choice words.”

Yip Sang having died 96 years ago, there is no one alive who remembers the Grand Old Man. In 1993, the 19th and youngest son of Yip Sang was interviewed at age 87 about his father by the Vancouver Sun.

“He was very strict with us and he would hit us, oh, with a cane. And he’d swear at us. And he made us work. And what he said was law,” said the late Yip Kew Yacht. “‘You shouldn’t play football, you waste your time. You should make money.’

“But we were spoiled, eh? He loved us, yes. He loved us a good deal; he worked hard and gave everything to us. Money for education, everything. He spoiled us. In fact, he made us incapable of making money. We were too dependent on him. We were educated and had good careers, but we didn’t have his facility for making money.

“That is how it is with the generations. The first generation makes the money, the second one spends it, the third revives the family’s fortune.... Today’s generation of Yips are doing very well.”

His words ring true 30 years later as the Yips are gathering on Pender Street.

It’s now time for the group photo. The lobby of the Chinese Cultural Centre, with its double staircases, is just big enough to accommodate everyone in tiers. Parents are pushing the younger Yips in strollers and adult children are guiding the older Yips in walkers to pack in tight to fit the frame.

Christina More of the reunion committee holds up a copy of the group photograph from the 2008 gathering for comparison.

“There’s more people than last time!” she says. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: