Just the other day, a retiree told the team preparing the Chinese Canadian Museum for its grand opening that she identified as “recovering Chinese.”

“For much of her life and career, she didn’t really think about talking about it,” said Grace Wong, chair of the board that oversaw the museum’s creation. “‘Am I Chinese or not Chinese?’ It was almost not relevant. But she said now, as she’s older, she really understands the value of not losing that history. And she wants to know more.”

The retiree’s experience of grappling with her identity has, for generations, been common for others who are part of the Chinese diaspora but grew up in Canada. The intersecting forces of assimilation, discrimination and cultural shame — or simply a lack of resources to turn to — can contribute to a confusing experience of heritage and belonging.

But this is changing. And Wong hopes the new museum will help more people understand themselves and each other, “both Chinese Canadians and non-Chinese Canadians,” she says.

On July 1, the Chinese Canadian Museum opens its doors for the first time. It couldn’t be housed in a more storied location: the Wing Sang building at 51 E. Pender in Vancouver’s Chinatown, first established as the business and residence of the legendary merchant Yip Sang.

While there are museums that tell parts of the Chinese Canadian story — in places such as Vancouver, Burnaby, New Westminster, Victoria and, before the 2021 fire that destroyed most of the village, Lytton — this is the national museum dedicated to the subject.

The Chinese diaspora was first recorded to have set foot in Canada 235 years ago.

“When people think about Chinese Canadians and when they first came, they think about the Gold Rush,” said museum CEO Melissa Karmen Lee. “But it actually predates that by quite a long time. The timeline begins in 1788. And it’s Chinese [people] coming to Canada as carpenters and having that interface and relationship with Indigenous people. That’s a really important perspective to understand.”

The Odysseys and Migrations exhibit near the museum’s entrance shows the start of that timeline when a British fur trader named John Meares recruited about 120 carpenters from Macau and Guangzhou to build a fortress and 40-tonne schooner at Nootka Sound, what was Nuu-chah-nulth territory. The timeline stretches to the present, noting the influx of immigrants from Hong Kong and Mainland China.

There are family photos too, sepia-toned images plucked from precious albums, that show that not all Chinese Canadians necessarily arrived or had ancestors who arrived from China directly to Canada. There are members of the Chinese diaspora who’ve spent time in India, Jamaica, Mauritius, Peru and Vietnam. There’s a school portrait on display that shows a kid named Howie who sticks out as the only Chinese face amongst his Nigerian classmates. Another shows Chinese kids petting a kangaroo in Australia.

On another wall in the exhibit is a colourful mural by artist Marlene Yuen, a comic book-style pastiche of images from throughout Chinese Canadian history. There are references to older chapters, like when migrants worked in farms and canneries, the right to vote, the proliferation of “chop suey” restaurants in small towns, as well as more contemporary scenes like Chinese malls in suburbia and seniors doing tai chi at the park.

Whether they’re of Chinese background or not, everyone will recognize something in the museum about life in Canada, says Lee.

Many lives at the Wing Sang

The Wing Sang is an exhibit in itself. As it stands today, the building stitches together 134 years of additions, challenging curious visitors to spot the seams where an extra floor might’ve been added or where an alley used to be.

In 1889, it started out as a modest two-storey warehouse, where Yip Sang ran his import-export company.

In 1901, he hired an architect to extend the building and add another floor. These additions can be clearly seen from the street. Then in 1912, Yip Sang built a six-storey residence across the alley behind his place of business, connecting the two structures with an elevated passageway that crossed over the shops and services below. Three of his four living wives and 23 children lived at the Wing Sang.

Yip Sang died in 1927, but there were still Yip family members living in the residence until the mid-1970s. In the years that followed, rainwater soaked into the building’s wooden beams and it was deemed structurally unsound.

In 2001, the family sold the building for $850,000, but it wasn’t long before that buyer put it on the market again. In 2004, real estate marketer Bob Rennie, nicknamed Vancouver’s “condo king” by the press, received a call that it was available. He signed a cheque hastily in a downtown Starbucks, even though he had never been inside the building, in order to beat another bidder.

After a lengthy renovation that cost $22 million, Rennie reopened the Wing Sang in 2009. Yip Sang’s offices became Rennie’s. And the rundown residences became the Rennie Museum for contemporary art, of which is he is an avid collector and lender. On the rooftop garden, Rennie planted poppies in reference to the opium Yip Sang manufactured on site before it was made illegal.

In 2017, the provincial Ministry of Tourism, Arts and Culture was mandated to establish Canada’s first Chinese Canadian Museum. A society was formed to shepherd its creation. They always had Chinatown in mind and looked at 22 potential sites. But when Rennie was willing to sell the Wing Sang to serve as the new museum, there was no contest.

“It was perfect,” said society chair Wong. “Where else could we go that we could actually set up a Chinese Canadian Museum, while preserving the history of this building?”

In 2022, the province gave $27.5 million to the museum society. While the purchase price wasn’t announced, Wong says that people have been guessing “pretty well.”

“It’s close to that, a little beyond,” she said.

The province has since announced more funding, bringing its grand total of museum spending to $48.5 million. The federal government recently announced $5 million in funding, which the society had been anticipating, as it is a national museum. Rennie has also said that he plans to contribute $7.5 million.

Amidst all the changes, one space kept as a time capsule is the children’s classroom on the third floor. The wood panels on the walls remain painted green as they always were. The blackboard has writing preserved beneath a pane of glass by Rennie.

The adjacent room, however, required a lot more reconstruction: the Yips’ living room, with a piano, phonograph and rotary phone.

“We’ve looked at over thousands of photographs, trying to match the wallpaper, as well as the tile on the floor,” said Lee. “We’ve been going to auctions and getting the furniture, getting the tables, getting everything exactly the same so that you will feel immersed.”

She pointed to a set of chairs — a perfect match for the Yip family’s — that was recovered from a house from Point Grey, a tony neighbourhood on Vancouver’s well-to-do west side.

It’s a reminder of Yip Sang’s status that despite his race in a racist era, his Chinatown home was filled with the likes of furniture that you would find in upscale homes in a wealthier, whiter part of the city.

‘Exclusion and excessive documentation’

The doorway into the main gallery is on the second floor. Stepping into it, visitors leave the building that served as Yip Sang and Rennie’s places of business and into what was once the residential building behind it.

Rennie hollowed out the residential floors for his museum, turning them into two large 40-foot rooms with white walls. Each is like being inside of a big cube. If you spot the window by the ceiling that looks out into the gallery, that’s where Rennie’s office used to be.

The first exhibit to be shown in this space is The Paper Trail to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act. July 1 is a fitting day for the museum to open, exactly 100 years since the Canadian government closed the door on immigration from China through its Chinese Immigration Act (widely known as the “Chinese Exclusion Act”), the culmination of years of anti-Asian racism in legislation and daily life.

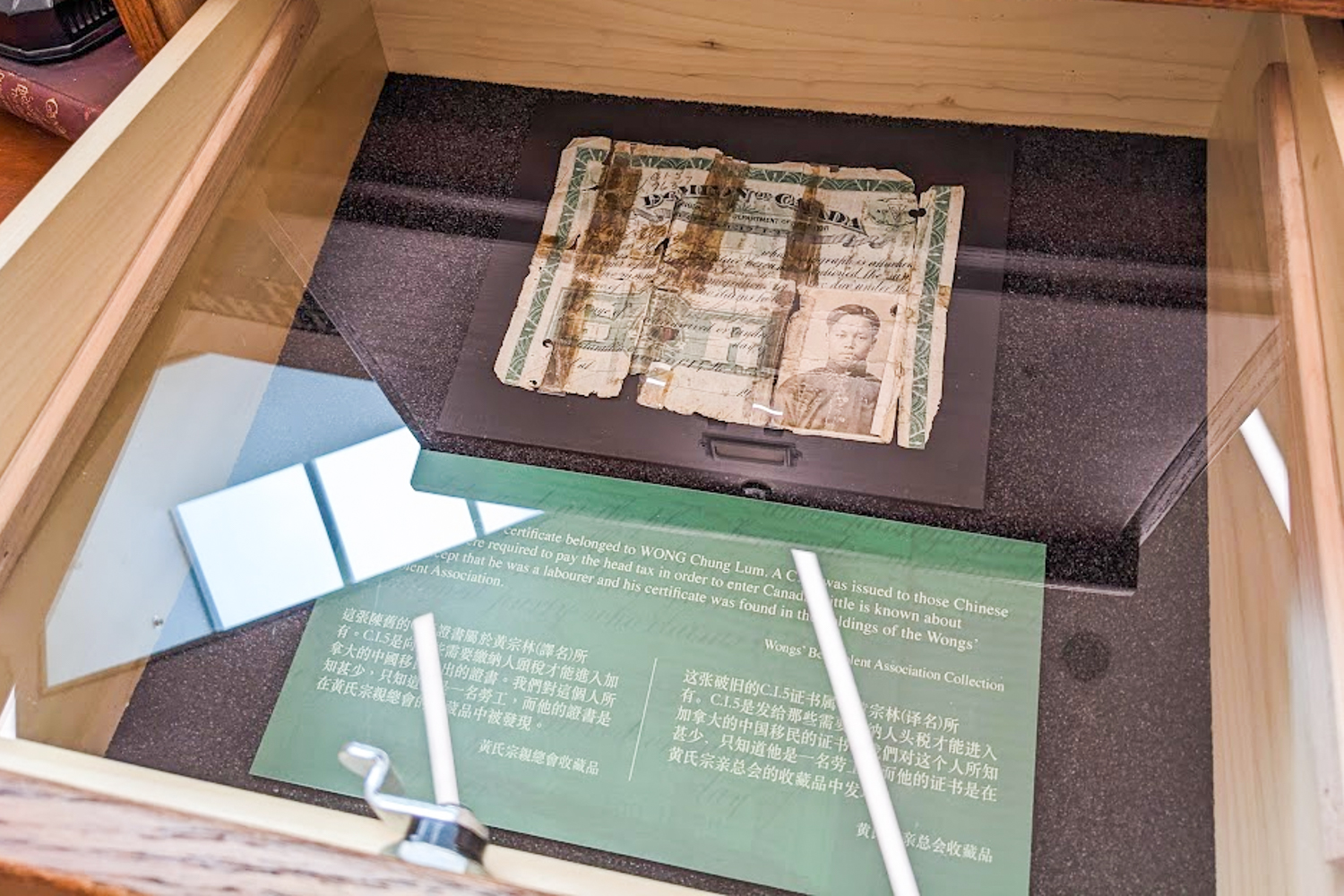

In the exhibit are large reproductions of Chinese immigration certificates. They were crowdsourced by curator Catherine Clement, who stresses their role in “exclusion and excessive documentation.”

“There are so few of these certificates in public archives,” said Clement. “The ones I’ve seen were all in someone’s shoebox drawer.”

In her work interviewing Chinese Canadian veterans, they would fume at the sight of them. That is, if they hadn’t destroyed them to avoid having to think about their painful legacy.

First issued in 1885, there were many types of certificates that functioned as receipts, identification and travel visas. They included documentation for the infamous head taxes and — when the “Exclusion Act” halted Chinese immigration 1923 — numbered cards for Canadian-borns to remind them that they were not Canadian citizens with rights.

There are dozens upon dozens of certificates on display, demonstrating how intensely the government tried to catalogue every Chinese body within its borders. The certificates were the first use of photo identification in the country, allowing visitors to meet this first generation of migrants face to face.

One of the walls is covered with certificates belonging to early Chinese children in Canada, citizens of nowhere because of their race.

Despite the heaviness of the subject matter, the babies and toddlers are incredibly cute with big smiles, fresh haircuts and cozy hats. There is a ball in the frame of one photo, likely to prevent the child from crying for what is an expensive photograph. To save on paying for individual portraits, a family with 10 children decided to take one group picture and cut out the images of each child instead.

Among the children is the certificate of a man with a sophisticated mustache. He is Won Alexander Cumyow, who in 1861 was the first ethnic Chinese person to be born in Canada.

It’s an impressive effort of crowdsourced material, but it begs the question: what about the people with no living descendants?

In order to surface them, Clement combed newspapers, migration records, hospital records and prison records to ensure they weren’t forgotten.

On display are patient files from the Essondale “Provincial Asylum for the Insane” in Coquitlam, later renamed Riverview, which tell of patients languishing for decades and refusing to speak. The province deported some, fed up with paying for their care. There are also stories of inmates and their brushes with racist juries. Tragedy often led to drug use.

And while the Yip residences were water damaged, Rennie preserved the brick wall, used as part of a unique corridor of the gallery which Clement dubbed “Bachelor’s Alley.”

Many Chinatown bachelors were in fact married to women overseas. The Chinese Immigration Act meant that they had no hope of reunification. Without children of their own, they spent time with children of friends and became known as their “uncles,” helping babysit and taking them on outings.

“What would it have been like for them?” said Clement. “To watch families but to have no family, to feel the fear of death, to feel shame, to feel a loss of hope.”

In the alley exhibit are photographs and stories of men who eventually died alone by suicide or of old age, one of whom was found in his tiny room on Pender Street at age 107, who had enjoyed some celebrity as the oldest man in the province.

“What’s most precious to me as a curator is the ones that have no one to tell their stories, and we’re telling them for the first time,” Clement said.

The “Exclusion Act” was repealed after the Second World War in 1947, lasting 24 years.

Chinese Canadian futures

The Chinese Canadian Museum in the renovated Wing Sang seems a world away from the disrepair of nearby buildings from the same era.

In the surrounding blocks, poverty is present in Chinatown and the Downtown Eastside. There are low-income immigrant residents who are still making a life here, against the odds. Chinatown is a rare neighbourhood that has all the culturally-catered shops and services they need within walking distance, but they’re gradually shuttering.

Then again, the Wing Sang has always been insulated from the world. Yip Sang the merchant and railway paymaster, with his four wives and 23 children, lived a very different life from the bachelor men brought over to labour. When Rennie took over the space, he marketed condos and displayed art in the middle of a neighbourhood where seniors wait in food lineups and high-end bars and boutiques are replacing the last of the Chinese businesses. Yet both men, titans of industry, are known for their philanthropy.

Vancouver’s Chinatown was the only area under consideration for the museum, with so many Chinese Canadians throughout history passing through the city and the neighbourhood itself.

Visitors won’t be able to resist pondering the state of Chinatown on their way to check out the exhibits, just as they contemplate the place of Chinese Canadians within its historic and ultra-modern walls. There’s more to come, as 65 per cent of the building is still yet to be turned into museum space. The museum will no doubt play an important role in the latest attempt to revitalize the neighbourhood.

In Chinese, Wing Sang means “everlasting.” With so many lives, the building is a testament to its name. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: