For a generation of children who grew up in boggy Richmond, cobbling together a frog catcher was second nature.

First, find an old can that once held coffee, tobacco, soup or tomato sauce. Then, look for a stick or a two-by-two. Maybe there’s one in the garage or the neighbour’s yard. With the help of a rock, nail the can into the wood.

With the frog catchers in hand, they descended into the ditches.

“Everybody I went to school with had ditches in front of their houses,” said Julie Pappajohn, who was born in 1955 and grew up on Francis Road. “We’d have our frogcatchers, we’d have our fishing lines, we’d have our bucketfuls of living things and bring them home.”

Pockets of nature have always been a lure for the children of the suburbs, whether it’s the creeks of Burnaby or the forests of the North Shore, tucked behind the subdivisions. But in Richmond, the children had drainage ditches instead.

In the years of the postwar baby boom, Richmond was filled with children playing by ditches, paddling down ditches, pole vaulting ditches and leaping over ditches. And yes, there were children who fell into ditches, to the agony of parents who’d hose off the muck.

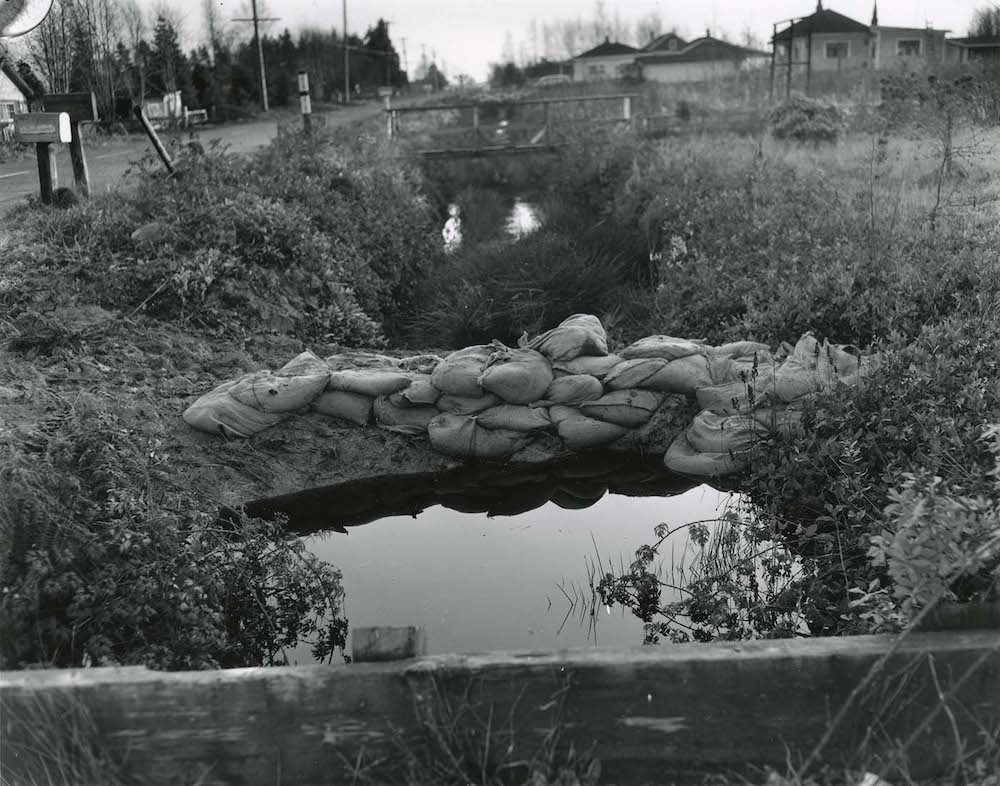

But the ditches weren’t dug to be played in. Richmond, an island city, sits at an average of one metre above sea level, which makes it prone to flooding. Basements can’t be built in the city because of this, and yards are often saturated with water. As a result, a gridded network of ditches were excavated for drainage, so that excess water from rainfall can be caught, carried off and discharged at the island’s edges.

The city’s nickname, inevitably, was “Ditchmond.”

Just about every house in every neighbourhood had a ditch fronting their property. To cross them, homeowners kept bridges made of wood or sandbags and asphalt. The upkeep was annoying, with Richmondites carefully dipping their lawnmowers at an angle to mow the grass that grew on the sloped edge of the ditch. To this day, drivers still steer their vehicles into ditches, with alcohol often a factor.

As the ditches became overgrown, swelled with water and were taken over by living things, children found them irresistible to play in. They might’ve been created to serve a practical purpose, but they were as wild as any wood.

Capturing this childhood, Pappajohn has an exhibit called Ditch, showing at the Richmond Art Gallery’s space at city hall. There are paintings and a video recreation of her frog hunting days, down to the tin can catcher.

“We were adventurers, we were scientists!” said Pappajohn. “Though it wasn’t all an idyllic fairy tale.”

For the exhibit, she dug into the history of local ditches, which have been around for over 160 years. They played a key role in the making of contemporary Richmond, created to master the waterways that crossed the island long before colonization.

Dawn of ditches

In 1861, Richmond’s first European settlers who wanted to farm on the low-lying Lulu Island, between two arms of the Fraser River, knew they had to protect their land from tides, storm surges and river floods.

They excavated earth by hand to create ditches, which drained water into sloughs and the Fraser, and piled up that earth to serve as dikes.

The growing population of settlers called for a public authority to take care of diking and drainage. In 1879, the municipality of Richmond was established. The young community employed the help of residents to set up its flood protection system, paying 10 cents per cubic yard of earth dug for new ditches. Long canals were also excavated to hold the excess water.

Because the river water was full of sediment and rain barrels often caught bugs and rats, Richmondites would even rely on ditches for water. However, the ditch water was extremely alkaline, which did not improve with boiling.

Thousands of years before ditches, the island had a natural system of drainage of its own: sloughs. They made up a vast network of channels that allowed rainwater to run off into the Fraser River. Fresh river water also flowed in and out with the tide. Over 100 kilometres of the sloughs were navigable by canoe.

It was a fertile landscape of bogs, grasslands and spruce forests. It was a natural garden of cranberry bogs and crab apple trees. According to an archeological report by the city’s museum, Indigenous families — mostly from Musqueam, Tsawwassen and Kwantlen and from as far as Cowichan, Nanaimo and Saanich — had the right to its resources. In 1781, smallpox killed many of the people who once came to the delta island.

When settlers came along, their human-made ditches and canals replaced many of those ancient waterways as they paved the land.

Harold Steves, 86, the longtime city councillor whose family established the town of Steveston, remembers his father telling him that he learned to swim in the slough near their home in the southwest corner of Richmond. When the city turned it into a canal, it became the younger Steves’ skating rink.

“All the kids would get together when the canal would freeze up, and we used to have a race from here to Terra Nova and back,” Steves once told me. The roundtrip totals over nine kilometres.

Back then, his family raised Holstein milk cows. One winter, the bull decided he wanted to join in the youngsters’ fun and walked to Steveston on the frozen canal. Steves was able to lure him back home with a bucket of potatoes.

Though Steves was born a few generations after Richmond’s first farmers, he too had encounters with flooded fields, which came in handy during the winter of his Grade 12 year when he played for the local hockey team.

“We learned all of our skills on Mah Bing’s field [the neighbouring farmer],” he said. “Mah Bing grew potatoes, and after the potatoes were dug, the field was quite level and filled up with water. We had a couple of acres of ice to skate on.”

Like other Richmond kids, he also played in the ditches, which were continuously being developed.

“We saw ditches as part of our recreation,” he said. “There were little salmon fry and minnows swimming up and down the ditch. We used to get a piece of window screen, tie strings on it, and when the little fish swam over it, we’d pull it out. It was great fun.”

Looking back, Steves now knows why there were chum salmon there: they were trapped within the ditch because of the city’s floodgates.

Frogs, rafts, slime

There is a Facebook group called “You grew up in Richmond, B.C. if you remember...” where ditches are a favourite topic. When I put out calls for ditch memories, I received over 350 responses.

Most of the respondents were from Pappajohn’s baby boom generation, which filled Richmond with children who were often left to play around the ditches unsupervised from a young age.

Between the 1950s and ‘70s, the population of school-aged children grew fivefold from 2,900 to 15,000.

In the 1960s alone, 17 new schools opened.

Frogs drew this generation into the ditches. To get as close into the ditch was possible, children tied rope around their waists or simply held each other as they lowered themselves in on their bellies. The cans for catchers came from a variety of household products, from Nabob coffee to Rogers syrup. These were often too sharp, hurting the frogs. But placing dandelion flowers on fish line worked like a charm, and the hungry frogs could be caught unharmed.

“As a really young kid who had no money but wanted to give presents, I [decided I] was going to catch a female and male frog to give to my grandparents as an anniversary gift,” wrote Alexis Schick. “Gramma was making a beautiful dinner and I came in the kitchen with my muddy arms behind my back and told her I had a present for them. I showed her the present and put them on the kitchen table. She had so much grace and said thank you very much and let’s put them in the pond.”

Tadpoles were also a draw, described as big as trout, and stickleback fish. Dragonflies flittered about and water striders skittered across the surface of the ditch water. Buckets and jars of ditch water and their denizens would be brought inside homes for children to inspect. Kiddie pools were used to hold frogs.

“The film is long gone, but we used to have Super 8 film of our dog, Rusty, drowning mink in the ditch in front of our house on Gilbert between Lucas and Blundell,” wrote Cassandra Harmony Tuan. “There was a mink farm somewhere in the area and every now and again a couple would escape. The ditches led them right by our house and in those days no one kept their dogs contained.”

Depending on the tide, the water could be fairly clear. But when it wasn’t, the children who fell in ended up covered in sludge and slime.

Whatever the case, many of the respondents shared about people falling in on holidays. Jen Netzlaw wrote about a friend who, on Halloween night, dressed up as a ninja turtle and fell into a ditch, ruining all his candy. Bonnie Beeston wrote about riding her new bike on Christmas Day right into the ditch.

Also on Christmas, Lori Cochrane’s grandmother slipped on the bridge over the ditch on a stormy night and fell in, along with the cake she brought for dessert. “Didn’t find the copper cake pan and lid till the following spring,” she wrote.

There were ditches big enough for children to build rafts to ride in out of whatever wood they could scavenge, paddling them under each property’s bridges. Jordan Scott Linger wrote about collecting the blades of broken goalie sticks, whose ends made for perfect raft paddles. Some children were lucky enough to traverse the ditches and sloughs on their parents’ skiffs.

There was a dark side to ditches too. A few people shared about being thrown into ditches by bullies. One notorious ditch for this was on No. 1 Road, leading up to Hugh Boyd Secondary. Losers of fights also went in.

“A cat had been in a ditch and there was a bunch of boys spearing the cat,” said Pappajohn. “And that traumatized me. I still remember running home crying. In my mind, I still remember them laughing.... You learned there’s an ugliness out there.”

Children also put frogs on the road for vehicles to run over.

“I think that that’s part of childhood too,” said Pappajohn. “Not really understanding something until you do it.”

City workers would often come by to dredge the ditches to prevent them from getting clogged. They would also fill in the old ones, which upset the children about the fate of frogs and led to a surge in rats.

‘River rats’

Susan Anderson told me about growing up on Mowbray Road in the 1960s, which formed a ring with Pigott Road, allowing her and her friends to skate on the frozen ditches around the blocks in an almost perfect oval.

“It was very affordable compared to Vancouver,” said Anderson of the houses. “It was very working class; everybody was in the same point.”

Because Richmond was developing fast to accommodate these families, constructions sites were everywhere. Naturally, children played in them too, climbing on top of piles of silt and crawling inside concrete pipes.

When Anderson got older, she was so used to seeing ditches that she was surprised to realize that they weren’t a common feature everywhere. That’s when she started hearing the “Ditchmond” nickname.

“It was used against us,” she said. “People from the city would prove that I was basically a hick from Ditchmond.”

It was the same for Pappajohn, whose father worked as a butcher a world away in Vancouver’s Kerrisdale, a tony neighbourhood known for its British character. The children of her father’s friends who lived on Vancouver’s west side called the Richmondites “river rats.”

The name calling stung. Whenever Pappajohn rode in the car from Vancouver back to Richmond, crossing the bridge over the Fraser River, smelling the pulp mills, she felt the distance between the two places.

“That’s what I discovered doing this project,” she said. “We had a relationship to water.”

Deeper into the ditch

Doing a project on ditches meant sifting through a lot of personal and crowdsourced memories for Pappajohn. But because ditches are ultimately infrastructure, she also ventured into the Richmond archives to read histories and examine old engineering reports.

She learned about the rich habitat on the island before the settlers arrived, how it became one of the most populated places on the coast during the late summer salmon season. Creatures like muskrats, which were often found swimming back and forth in ditches, have been here a long time.

She learned about Joseph Trutch, who recently had his name struck from a Richmond street, the province’s first lieutenant-governor and former land surveyor who pushed for the shrinking of reserve lands for Indigenous peoples.

Pappajohn was an art educator for 20 years in the North Vancouver School District, always involving history and culture.

“This had me thinking, why did we not learn about this in school?” said Pappajohn, who felt “cheated” of what really happened. “I did a lot of thinking about what difference would it have made if we knew.”

Pappajohn’s exhibit features works with grassy yellows, murky greens and clear blues that fill the canvases, drawing you into the immersive banks of a Richmond ditch.

The ditches, of course, are still around. If your parents let you, you can play in them. The occasional driver still crashes into them. And the occasional body is fished out.

Pappajohn’s project on her former hometown gave her an excuse to give herself an education on Richmond’s many murky layers of displacement and development. The natural sloughs and channels that cut across the island might’ve been only a fragment of their old grandeur by the time Pappajohn was born. But her ditch on Francis Road was enough of an echo of that history.

“If you’re connected to a waterway as a child, it doesn’t matter if it’s a ditch or a big puddle. It’s a connection to a living thing.”

‘Ditch’ is on view at Richmond City Hall until Sept. 13. ![]()

Read more: Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: