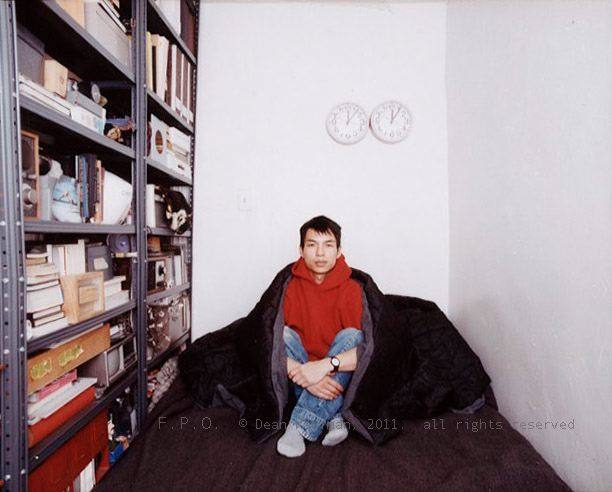

Tobias Wong was ahead of his time. The Vancouver-born artist died at age 35 in his New York City apartment. Many wished for more time with him. The title of a new exhibition of his work at the Museum of Vancouver captures this desire. As curator Viviane Gosselin explains, the title was a play on words about conspicuous consumption, but also summed up the feelings of the staff at MOV as they put together the show.

All We Want Is More: The Tobias Wong Project is an encompassing look at Wong’s cheeky body of work.

Many of Wong’s most irreverent works took as their impetus the things that we wear. Jewelry, watches, T-shirts, mittens or bulletproof brooches figure heavily in his work.

Ballistic Rose, part of the Museum of Modern Art's 2005 exhibition SAFE: Design Takes on Risk, was a Kevlar blossom designed to stop a slug and look pretty at the safe time. It is a good summation of Wong’s many interests and obsessions — sex, danger, beauty, fashion and a cheerful kind of perversity that upends even as it delights.

Born and raised in Vancouver, Wong started his career as a provocateur early. As a first-year student at Emily Carr University of Art + Design, Wong’s contribution to the year-end Foundation show was a precise arrangement of live goldfish in plastic bags. The installation brought about a call to the SPCA. Overnight, Wong swapped out the live fish for canned tuna.

After studying architecture in Toronto, Wong continued his studies at the Cooper Union, a private New York City college where he further developed his signature style of shit-disturbing sweetness. The unlikely combo still packs a sizable wallop.

Many of Wong’s most iconic pieces riffed on the dissonance of unlikely pairings, such as piranha fish and Swarovski crystals, precious pearls and black rubber, gold flakes and human poop. Iceberg Chandelier, which Wong created with Amelia Bauer for the 2005 Art Basel Miami Beach, required the artist to source the piranha illegally. Upbeat criminality in the pursuit of art is something of a theme in the current MOV exhibition.

Amongst the many exquisitely crafted objects are cease-and-desist letters from the corporations that took issue with the designer’s appropriation of logos and other branded materials. Fashion houses Issey Miyake, Burberry and Ralph Lauren were all the subject of Wong’s purloining.

Sometimes, it worked out in the most unexpected fashion (heh). When Wong repurposed Burberry’s famous plaid to make buttons, stylish cognoscenti snapped them up. The fashion house took note and ended up using the pirated buttons in their own advertising campaigns.

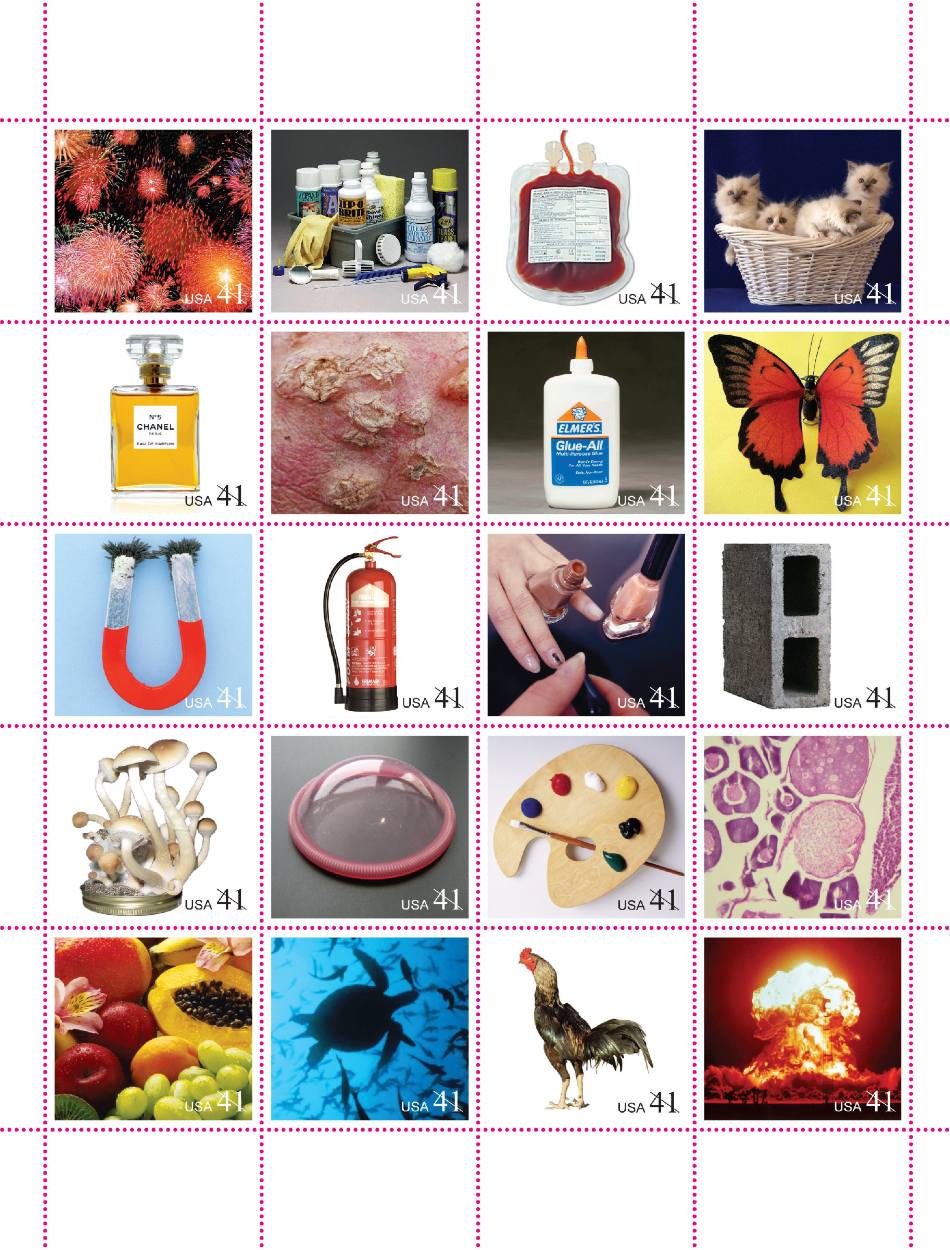

Straddling the arenas of visual art, performance, design and mind-fuckery, Wong’s work is filled with loopy inversions, swapping high for low and vice versa. The experience is a little like being on a conceptual roller coaster. One moment things are right side up and the next hanging in midair, borne aloft by outrageous wit and a curious form of bravery. In this interstitial instant, it is possible to see art and design anew.

Beauty is also a big part of the show.

Many of the objects on display are remarkable not only for the cleverness of conceit but also for their extraordinary execution. Gold plated stir sticks. Dimes embedded with diamonds. Leatherbound bondage watches. A neon sign that cheerfully reads "ANUS" in big glowing letters. The anus sign was displayed in the window of Wong’s Manhattan apartment and it is recreated in golden name-plate necklaces, akin to the kind worn by Carrie Bradshaw in the Sex and the City series.

Even the lowliest of things, human poop for example, can be rendered beautiful by the addition of gold and silver flakes. Wong’s edible capsules entitled Shitting Gold, filled with precious metal, were designed to be swallowed to make glittering stuff come out the other end of people.

A dozen years after his death, the MOV exhibition reveals how many of the themes and ideas that animated Wong’s work are more prescient than ever. The haute couture meets street punk ethos that has fuelled the work of designers like Virgil Abloh, fashion houses such as Vetements and Supreme is abundant in Wong’s work.

In addition to his skill as designer, Wong was also a genius of collaboration, with a knack for identifying other like-minded folks from candy maker Papabubble to furniture design house Cappellini.

But above all, the man was extremely funny. It’s rare to walk through an art exhibition and laugh out loud, but this happened to me a number of times in All We Want Is More.

The kinkier, more fetishistic aspects of Wong’s work are balanced by this puckish sense of humour, which infuse his rubber-encased pearls in a Tiffany’s blue box or a gold-plated McDonald’s coffee stir stick. McDonald’s discontinued the infamous sticks when they became synonymous with cocaine use, but Wong revived them with a flourish and received another cease-and-desist letter for his efforts.

In this appropriation and repurposing, Wong’s work draws upon a long tradition of creative troublemakers. Artists like Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dalí and Andy Warhol are evident in his work, as are fashion designers like Elsa Schiaparelli and art movements (the Dadaists and Fluxus folks).

Like Duchamp’s readymade sculptures, many of Wong’s creations took items already in existence, whether that was a Philippe Starck Club Chair or a Alvar Aalto Savoy vase. Wong’s Aalto Door Stop was created by filling one of Aalto’s vases with cement and smashing the precious glass to extract the rough object from within, which was then used to prop open doors.

This blend of prankish, razored wit effectively transformed objects with a seemingly simple elision. The addition of an interior light source in Philippe Starck’s Bubble Chair in Wong’s most famous work This Is a Lamp was a story unto itself. Wong was able to snag a copy of the chair even before its official U.S. debut, much to the consternation of the company that made them. If brazenness is art form all on its own, Wong was also a genius of getting away with the most outrageous acts.

After seeing one of Wong’s pieces, you can never look at the original thing in quite the same way. Killer Ring is a prime example. A diamond solitaire with the pointy end of the gem sticking out from the band, it becomes an impromptu weapon, as well as enduring token of love. If your beloved spouse disappoints you, the ring is a means of cutting, carving and gouging, creating all manner of mayhem.

The attacks on New York City on Sept. 11, 2001 impacted Wong’s work profoundly. There is both grief and violence mixed into works like a matchbook, carved out to resemble the Manhattan skyline, with only two unlit matches standing in for the Twin Towers. There’s a chrome-plated box cutter, similar to those used by the terrorists who hijacked the planes, engraved with the words “Another Notion of Possibility.”

When industrial designer Karim Rashid chose to release his book I Want to Change the World a few weeks after 9/11, Wong carved out the shape of a gun from the hardcover edition of the book. In an interview with NPR, the concept was explained in commentary so sharp it hurt: “Karim Rashid calls Wong's gun-shaped version of his book an astute critique of the power of design, the loaded agenda of changing the world.”

As much as he gleefully purloined other people’s stuff, ultimately Wong was his own singular creation. Nowhere is this more cheekily delivered than in a 2007 work, where he sent a blond, blue-eyed colleague to give a lecture at a design conference pretending to be Wong himself, while the actual designer sat in the audience as anonymous attendee.

All of this inversion/perversion/subversion was in the service of making people see anew or see differently, revealing the shocking beauty of ordinary things hiding in plain sight, whether they were matchbooks, a Bic pen cap or a mason jar. One of the artist’s most well-known works involved filling canning jars with solar batteries so that people could use them as gold-filled light sources. It is beautiful, both conceptually and in the flesh.

Wong died in 2010 in New York City. Although his death was ruled a suicide, his partner Tim Dubitsky maintained that Wong had died accidentally while sleepwalking. The artist had a long and complex history of different sleep disorders, including chronic sleepwalking and night terrors. Following his passing, the New York Times dedicated a feature to his life and work that questioned the official cause of his death.

As much as it an enormous pleasure to see the work collected, it is hard to escape the sadness that attends it. The quality of “what if?” lingers. I thought about where he might have gone or done, had he lived. Reading previously published profiles about him is a little like hearing a wickedly funny ghost.

While walking through the MOV exhibition, a woman approached me. “Do you like the show?” she asked. It turned out to be Wong’s mother. In addition to being an artist and designer, Wong was a beloved child, brother and son. We chatted and she took a couple of photos. The exchange was so bittersweet that it stays with me still. If only I had Wong’s bulletproof brooch to protect my heart. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: