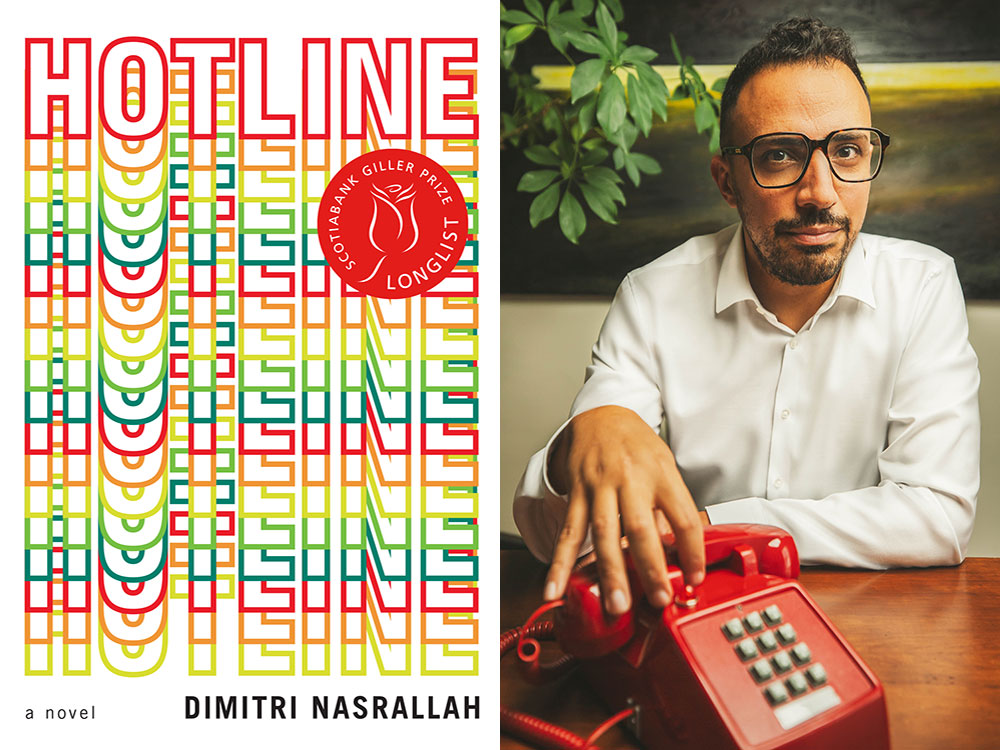

Dimitri Nasrallah and his newest book Hotline, out from Véhicule Press, have a lot to say about home and identity.

Home, wrapped in emotions and familial ties, is a difficult term to quantify. Through the eyes of a newly arrived immigrant to Canada and single mother, Muna, Hotline explores the delicate balance between acclimation and assimilation. Dejected by rejections from jobs she’s qualified for, Muna begins working as a consultant at a weight loss centre. As part of this, she anglicizes her identity, becoming Mona. As Mona, she fits in, finds success and is able to provide for her young son Omar.

Much of her early cultural exploration begins with the yellow meal boxes she brings home from work, in an attempt to save money on groceries. An assortment of low-calorie, mostly tasteless soups, ravioli, pizza and pot pies get her and Omar through their tough, first winter in Canada.

Nasrallah will be discussing Hotline as part of the Vancouver Writers Festival panel What Home Means, taking place Oct. 18.

Ahead of this event, Nasrallah and I spoke about many of the aspects of the book that appealed to me as a recent immigrant who often struggles with her own identity and sense of belonging. I enjoyed Hotline's interplay of Arabic and English, for example. Nasrallah wanted Arabic words to reveal themselves through context, repetition and usage. Adding a footnote, he said, or italicizing the language, would only serve to make it feel exotic. “It was definitely a big consideration going into the project,” he said.

Here’s my conversation with Nasrallah, edited for length and clarity.

The Tyee: The idea of identity is explored extensively in Hotline through Muna’s experience moving to Quebec from Lebanon. How much of that reflects your own experience?

Dimitri Nasrallah: This story, or the inspiration for it, has been sitting with me for over 30 years now. I moved to Quebec with my family when I was about 11 years old in 1988. We lived in a very similar apartment. My sister and I shared the bedroom and my parents, the pullout couch in the living room for an entire year.

I always look back on that year as one of discomfort and almost impoverishment. We were living in Greece before that, and we had a relatively comfortable existence compared to what came after. When we arrived [in Canada], it felt as though everything had been lost and we had to be rebuilt from scratch.

Although we’d lived in several places before that where we didn't feel we had to sacrifice our identity as much, moving to North America in the ’80s, before the internet, was quite isolating and forced you to really begin all over again. That experience really stayed with me.

We were put in this situation where we had to decide if we were going to hold on to parts of our identity that we were quite familiar with, but ultimately, were not very useful to us here, or if we wanted to be pushed into these new identities, especially in Quebec, where I had to learn French which essentially replaced my Arabic because there was nowhere to use my Arabic then. Identity became an either/or type of choice. You couldn’t mix the two.

We didn't really have a community to connect with it. The people who moved here with us and held on to more of their Lebanese identities had a very hard time and ultimately moved back to Lebanon after several years.

At the end of the novel, Muna decides to take on a relatively new (to her) identity, in what seems like a fresh start. Would you call that assimilating?

I think I would because it's not necessarily a happy ending. Muna sacrifices this self that she knows quite well that no one should really have to sacrifice for the sake of their environment. But at the end of the day, she's worn down by the hurdles and constant challenges of this new life. So, she negotiates with herself and ends ups deciding to let part of it go for the sake of an easier path forward. There’s a bit of a tragedy to it.

Systemically, it's quite difficult to hold on to your identity and deal with the challenges of having to navigate this new life where you don't quite know the rules that are around you and must learn that as you go. On the one hand, it marks the end of a very difficult year for them but on the other hand, it also marks a surrender to a world that's not going to bend for her and is forcing her to bend towards it instead.

Language can be a huge factor in assimilation, as we see in the instance of Omar’s teacher Monsieur Pierre, who insists that Muna speaks French at home to improve his language. Was this your experience as well?

That teacher was based on the teacher that I had in my first years [in Quebec], who was quite like the one in the book, quite ardent about the use of the language. I remember getting little story assignments back so thoroughly marked up in red ink that halfway through, the teacher told me that he decided to give up on even correcting my work. That stayed with me.

It made me unconfident with learning French beyond that point, and I no longer wanted to learn the language, which really shortchanged my experience and my education at the time. So, I really felt a lot of those very same challenges and emotions that Omar experienced in the book.

What was the pivotal thought or experience that inspired you to write this novel?

I think, on the one hand, it was the yellow food boxes that appeared in our house right after we showed up. I always remember them as this curiosity, part of a new culture that I'd never really experienced before in the Middle East; this idea that you could commercialize weight loss in this way and sell diet plans. It just wasn't part of the language that I was familiar with. Since at the time we really didn’t have much access to the culture, we were largely invisible and on our own when we showed up, we just had the radio, television, and these boxes that my mother brought home from work. It always stayed with me.

As I got older and became a parent, I began to see the boxes as being this symptom of a larger problem. The systemic problem — why my mother couldn't continue with her profession when she arrived here and what, as a child, I thought of that one year where I was largely ignored and felt like my needs weren't quite being met.

I had a child's complaints about that episode, but the older I got, the more I began to see the challenges that my mother specifically had to navigate when she came here, and I wanted to write this book to show her that I see that side now and to communicate that to her.

What was your mother’s response to the book?

This is the first book, she says, where I don’t feel like an angry young man anymore. And I think she’s right, there's a maturity in the book that wasn't there before.

In my 40s, I began to see things differently — less with myself at the centre and more in contrasts, the greys between the blacks and whites. There's a greater understanding, and sympathy for what people go through than what may have existed in my previous work.

Raising your own child, you begin to see that you have to be more sympathetic to other people's trials. It's not a sign of weakness to let your emotions show. There were things that I had to relearn along the way since I’m now responsible, not only for myself but also for my family. A lot of that really came through being a parent and navigating someone else's experiences for them. You always want to avoid repeating what happened to you when you're a parent, especially if it's a matter of misgiving.

What are you hoping readers take away from Hotline?

Even though this is a historical novel, not much has changed. We still have these systemic barriers in society. We talk about immigration in one way but the reality of it is quite different. We say there's no problem because we choose not to look at what the situation is like for people once they’re here.

I think there is always work to be done in terms of how we see people and how much of people we don't see. And that may wear a different skin now than it did in the 1980s, but I think the core problem is still the same. Beyond that, I think I would like people to see that a lot of people who come here exhibit a great deal of resilience and overcome some very serious systemic barriers trying to build their own communities on an individual level, with the people they need around them.

We live in societies that are filled with individual kindness, but still have systemic feelings placed around that individual kindness. So, a lot of people who are integrating into society still find themselves navigating between individual advances and being held back by society at large.

I've also heard back from several readers and a lot of people really do see themselves, either their own stories or their parents’ stories, and that we tend to want to wash the entire story with the brush of overt racism sometimes, but sometimes that kind of outsiderness is more subdued than open complaints about race and culture. It's this invisibility that people suffer through. That is really the great indignity that comes with immigration. Ultimately what I wanted to do with this book was to articulate that loneliness in a particular way and I think a lot of people recognize themselves in that.

Dimitri Nasrallah will be discussing 'Hotline' as part of the Vancouver Writer’s Festival panel What Home Means, taking place Oct. 18. ![]()

Read more: Books, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: