On a very hot afternoon late in August, I place above my digital scanner a single rose. The rose is a hybrid tea with the official name Rosa "Mrs. Oakley Fisher" and as I look at this descendent of a burst of yellow first propagated in 1932 I am struck by a wave of nostalgia and melancholy.

Eighteen years ago I photographed my granddaughter Rebecca, who was seven at the time, wearing a sailor dress and, in her hair, a bloom of Mrs. Oakley Fisher from our garden. My wife Rosemary and I instantly decided this was our favourite rose variety. Later, when Rosemary and I moved to a Kitsilano duplex, Mrs. Oakley Fisher did not survive the transition.

And then, on Dec. 9, 2020, Rosemary died.

A month before, she’d instructed me to buy a terracotta pot and some dirt. She did not elaborate. Two months after she passed, the doorbell rang and outside was a package from Toronto with a specimen of Mrs. Oakley Fisher.

However, within three months, Rosemary’s final gift was but a memory. I hadn’t been able to make it grow.

My adventure with roses began in 1988. Rosemary and I were living in a house with a large corner garden in Kerrisdale. Rosemary told me we were going to a meeting of the Vancouver Rose Society at the Floral Hall of Van Dusen Gardens. After an hour of sitting on an uncomfortable chair and being subjected to a projection of 100 bad rose slides I admonished Rosemary for it.

Soon I came around and we had in our garden about 85 roses, most of them OGRs, or old garden roses. It was then that I decided that I would never photograph individual roses. To me it seemed like focusing on the nose of a photographic subject.

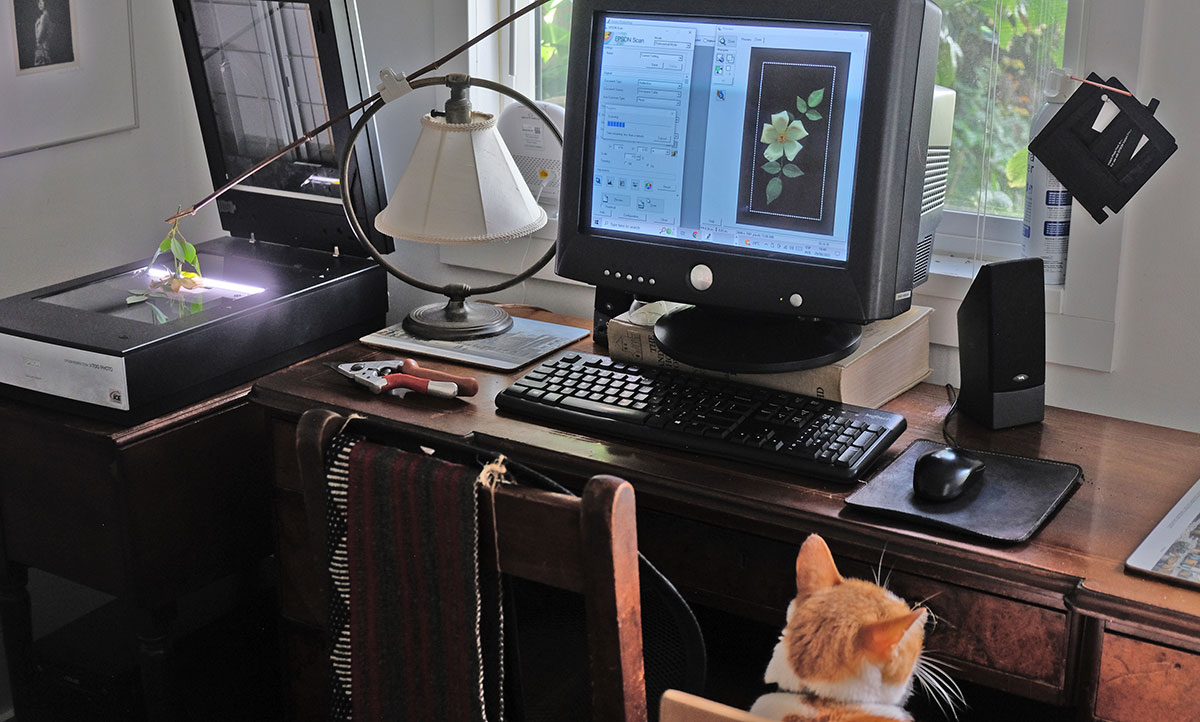

All changed during a lazy 2001 summer. I was bored and I had an idea of using my Epson scanner (a 1640SU at the time). I went to the garden and cut a difficult-to-grow Bourbon rose called Rosa "Reine Victoria" (a French joke so that the Brits could not give another rose their queen’s name!). I was lucky that first time. I had an art deco lamp on my Edwardian desk. I would clamp the rose on one end of a bamboo stick and the other to the lamp.

The vivid detail this rendered can be observed in the images accompanying this piece. I began to note the little things about my plants. I learned to appreciate a rose before it opened. Many of my scans included very small insects.

Canadian author Ross King, in his book The Judgment of Paris: The Revolutionary Decade That Gave the World Impressionism, explains that when Joseph Nicéphore Niépce’s heliographs (1827) and Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre’s daguerreotypes (1839) shocked the art world, the day’s richest French painter Ernest Meissonier, famous for his extremely detailed renderings of Napoleon on his horse, realized his moment was over.

The impressionists, writes King, created their fuzzy art to compensate for the sharpness of newly arrived photography. Early 20th century photographers Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen later sought to reference the dreamy effects of impressionism, but soon gave it up and started the f/64 club in San Francisco that featured ultra-sharp images.

All along, the visual arts of painting and photography have copied each other and you might note deep, dark, blue skies in the hyper-realist paintings of Alex Colville that mimic the effect of a polarizing filter on a camera’s lens.

Nowadays anybody can sport a macro lensed camera or a close focusing phone. Yet I am only interested in producing images of flowers made with my scanner, which can outperform a high school microscope and reveal some aspects of character that cameras do not.

When I worked as a magazine portrait photographer, I always did my best to respect my subjects and to somehow draw out their essence. My scans of the plants and flowers of my garden are made with a similar intent. I want to respect what a plant is. I tell some of my friends that I am a scanographer. And that my scanographs are of plants that communicate to me when they are at their best. Of late I have begun to appreciate the beauty of roses that are past their “best before” date.

That initial scan of Rosa Reine Victoria was one at actual size. I was careful to get the correct colour. I have similarly made some 3,000 flower scanographs since, each with name and date. I do this now using an Epson Perfection V700 Photo flatbed scanner, a 19-year-old edition of Photoshop and a very good cathode ray tube monitor. I do not close the scanner lid, as that would squish the plants. Why, then, is the background dark? The light behind the plants is affected by something called the inverse square law of light. What that means is that by the time the scanner sees my office ceiling it will be black. I make tiffs that are 800 dpi. That means that my scanographs are capable of being blown up to be almost wall-sized.

Best of all, arranging the leaves and the flowers is lots of fun.

The most important emotion I feel when I scan a rose, or one of Rosemary’s many rare perennials (she was a snob), is of intimacy with the plant and with my wife and what used to be our garden but is now only mine.

Somehow, to have that scan of Reine Victoria, and of many more roses and plants that gave up the ghost, gives me the comfort that a part of them is still with me. I feel the same about Rosemary when I look for plants to cut and scan.

Last fall I bought three Mrs. Oakley Fishers from an Oregon nursery. Two of them did not last long. The third one lives, is lovely, and will grow well. It has already given me four blooms. Somehow this Mrs. Oakley Fisher finally brings me the joy that Rosemary intended to share with me when, in the final season of her life, she quietly arranged her posthumous gift of young roses the colour of the late summer sun. ![]()

Read more: Art, Photo Essays

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: