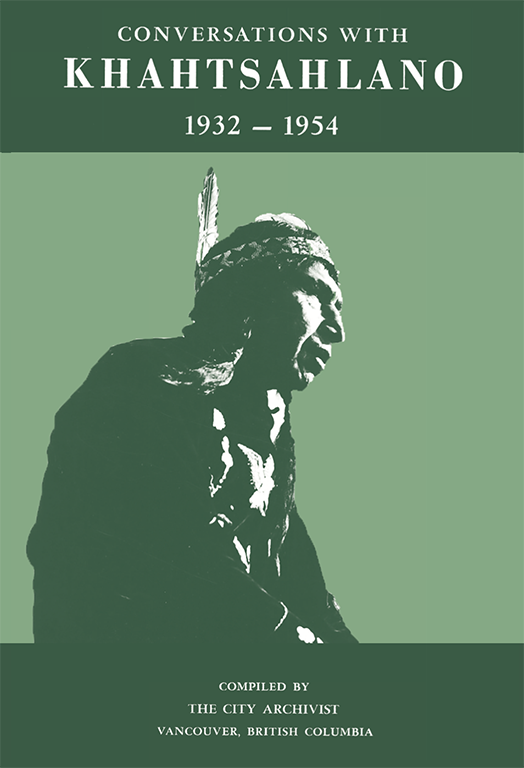

- Conversations with Khatsahlano, 1932-1954

- Talonbooks and Massy Books (2022)

It was a home then — several homes actually. Before it became Stanley Park in 1888, small settlements with people of Indigenous, European, Chinese and Hawaiian ancestry dotted the forested peninsula to the west of Vancouver, then just in its infancy.

There were roaming horses and pigs and cows, whose milk Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Chief August Jack X̱ats'alanexw said his mother would deliver to the Hastings Mill, the city’s early industrial heart. In the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh village of Chaythoos, which once stood at Prospect Point, his family had a little vegetable garden where they grew potatoes and carrots. Then came the swing of an axe, a presage of what would come after.

Shortly before Stanley Park was established, a young X̱ats'alanexw and his family were sharing a meal inside their Chaythoos home when road surveyors began chopping at the side of the house. His sister, Louise, the only one who could then speak English, tried to figure out what was happening.

“We’re surveying the road,” one of the workers told her. “Whose road?” she asked. “Is it whiteman’s?” They assured the family the road would run around the home. That wasn’t true. It would soon cut straight through where their home once stood, displacing the family, along with the rest of the village. Over the coming years, the remaining residents of what is now Stanley Park were also uprooted, sometimes through violence.

“Of course, whiteman did not say park,” Chief X̱ats'alanexw recalled decades later. “They did not call it park then.”

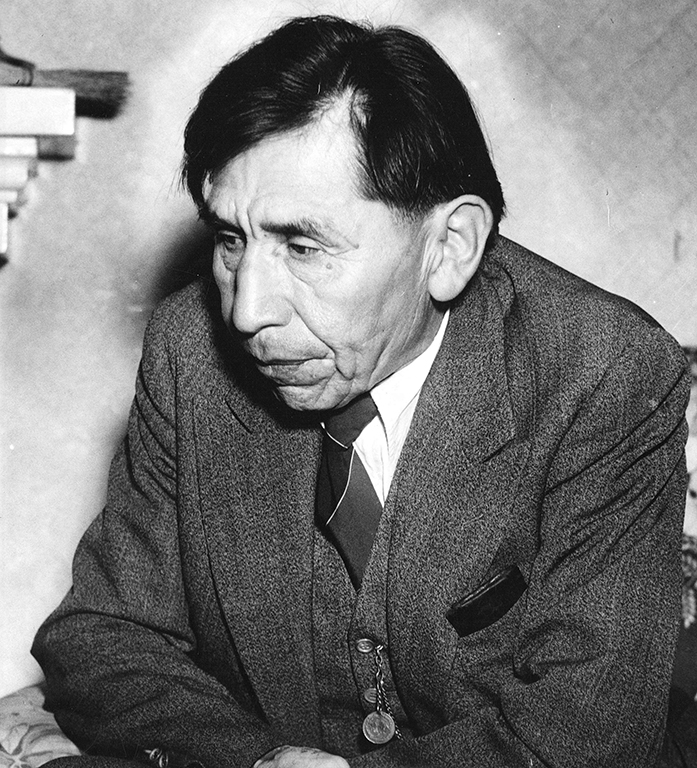

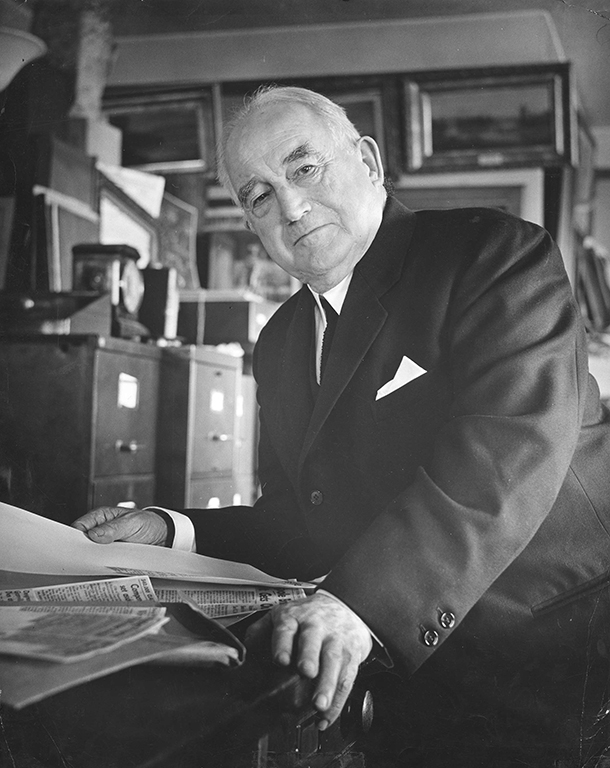

This poignant scene arrives about 50 pages into Conversations with Khahtsahlano, a sprawling book of letters, illustrations, documents and, fundamentally, more than two decades of conversations between the famed Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Chief and Major J.S. Matthews, Vancouver’s first archivist. Less a literary work than a scrapbook, it provides an invaluable window into Sḵwx̱wú7mesh life, culture and tradition around the time of Vancouver’s founding.

After decades out of print, Vancouver-based Massy Books and Talonbooks, in collaboration with the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Nation, have now republished a facsimile copy of Conversations. (The book’s full title is Conversations with August Jack Khahtsahlano, born at Snauq, False Creek Indian Reserve, circa 1877, son of Khaytulk and grandson of Chief Khahtsahlanogh.)

It’s a fitting moment. Last week, the Squamish Nation broke ground on its much-talked-about Sen̓áḵw development, an ambitious 11-tower residential project located on a sliver of reserve land — once a Sḵwx̱wú7mesh village called Sen̓áḵw — near the south end of the Burrard Bridge. The 6,000-unit development, all of which is expected to be rental housing, has roiled nearby residents.

The book paints a vivid picture of Sen̓áḵw long before the area became home to Vanier Park, the H.R. MacMillan Space Centre, the Museum of Vancouver and countless other attractions.

It’s where Chief X̱ats'alanexw and his family migrated after they were pushed out of Stanley Park. By this time, the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh settlement was known as Kitsilano Indian Reserve No. 6. Then it became the site of another forced eviction when the provincial government expropriated the reserve in 1913. Chief X̱ats'alanexw was this time driven from an area named — as he was — after his own grandfather, placed on a barge and dropped on the North Shore. The village was razed.

But that injustice gets scant mention in Major Matthews’ book. For the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh and neighbouring Coast Salish peoples, Conversations is an indispensable record; it’s been used to support land claims. Still, it’s hard to read the book without wondering what the archivist may have left out.

‘It's like talking to an Elder’

It was Linda Daniels, one of Chief X̱ats'alanexw’s great-granddaughters, who pushed to have Conversations reprinted. She first discovered it nearly 30 years ago, then unaware that she was related to the book’s subject. It immediately connected with her, particularly the text’s repetitive, conversational cadence.

“It's like talking to an Elder,” Daniels, now 70, said. “They’re repetitive. They always say it more than once. They want you to remember it.... They repeat the story until it becomes our story.”

Her mother, X̱ats'alanexw’s granddaughter, had seldom talked about her own family after she married Daniels’ dad. She too fell in love with the book, sleeping with it under her pillow. “It became a part of our lives,” Daniels said. But when her mom called Chief X̱ats'alanexw grandpa, she didn’t take it literally at first. (“We call a lot of people ‘grandpa’ or ‘uncle.'”)

Daniels ended up buying 40 copies from the city archive, which had only printed 500 when it released the book in 1967, only months after X̱ats'alanexw died. It’s unclear if the city ever printed more. Daniels handed them out to other Sḵwx̱wú7mesh people and sold them to interested students until she ran out.

“I was always on the search for the book,” she said. “In all of the bookstores, garage sales. Anywhere I went, I looked for the book.”

But they were rare and could sometimes fetch upwards of $600. When she found out Conversations had entered the public domain, she started looking for someone who could print more, which led her earlier this year to Patricia Massy, owner of Massy Books in Vancouver’s Chinatown. “It wasn't a hard sell,” Massy said. Since the April announcement that the book was being reprinted, Massy Books has received at least 400 preorders.

‘A guest of the city’

Centred on countless interviews with X̱ats'alanexw — all dutifully typed and indexed by the archivist’s assistant, Mrs. Alera Way — Conversations reads, and was written, in fits and starts. There are no chapters, the page numbers are inconsistent, and the book frequently bounces between topics, interpolated with little sketches or photos or contextual notes.

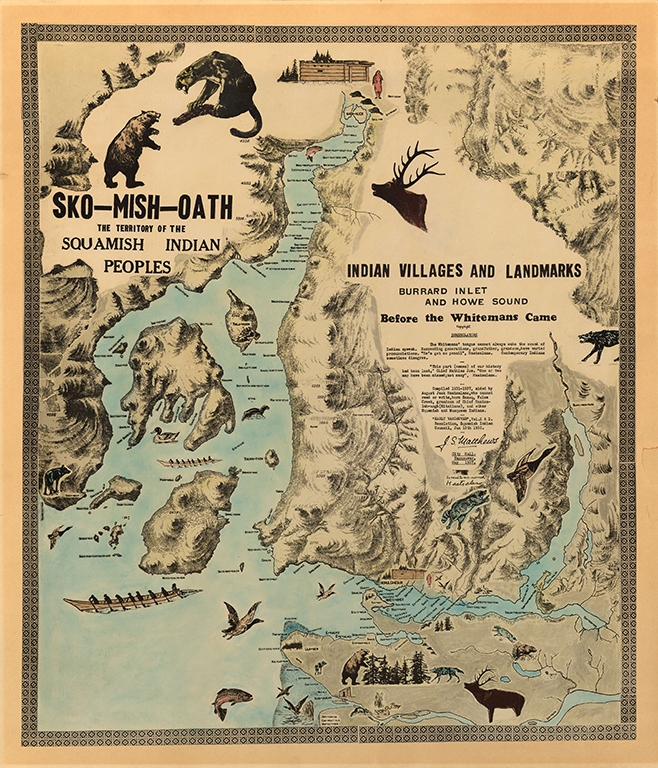

It can make for a disjointed read, but it brims with vivid detail: Sḵwx̱wú7mesh vocabulary and local place names (and corresponding maps); family lineages and lore; traditional Sḵwx̱wú7mesh duck hunting techniques, architecture, social organization, canoe design, tools, diet and customs. There are detailed transportation routes, appraisals of local rumours and casual commentary on the myriad effects of colonialism: “Everywhere whiteman goes, he change food.”

Some of the most memorable passages come when Chief X̱ats'alanexw recounts his experience with displacement. Here he talks about what happened after the province expropriated the Kitsilano reserve:

“The remains of those buried in the graveyard on the reserve close to First Avenue, about the foot of Fir or Cedar Street, were exhumed and taken for reburial at Squamish,” Chief X̱ats'alanexw told Major Matthews, though his account appears to have been reworded for the book.

“The orchard went to ruin, the fences fell down, and the houses were destroyed. A few hops survived and continued to grow until the building of the Burrard Bridge covered them up. I received a formal invitation to be present at the opening of the great bridge as a guest of the city." (Emphasis, my own.)

In her short story “Goodbye Snauq,” the late Stó:lō writer Lee Maracle says the ancient settlement, long a seasonal outpost among the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh and xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, once stretched along False Creek, all the way to Clark Drive in East Vancouver. Like Major Matthews, Maracle spells Sen̓áḵw differently.

“It was a common garden shared by all the friendly tribes in the area,” Maracle wrote. Fish, ducks, oysters, clams, wild cabbage, mushrooms, berries, camas, a purple flower from the asparagus family. “Summer after summer the nations gathered to harvest, likely to plan marriages, play a few rounds of that old gambling game Lahal.”

British Columbia’s attorney general, William Bowser, who was instrumental in pushing the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh out of Sen̓áḵw, described the village as an “eyesore to the citizens of Vancouver” and the eviction as “one of the best real estate transactions ever carried out in the province.”

In his own words — sometimes

Chief X̱ats'alanexw was, by all accounts, a darling of the Vancouver aristocracy. Newspaper reports have the “prominent Indian” lunching and exchanging gifts with the mayor. After X̱ats'alanexw was forced out of what’s now Stanley Park, he was asked to perform a dance at the opening ceremony, which he did once more at a rededication to the park in the early 1940s.

An article published in the Vancouver Daily Province a few days later revealed that X̱ats'alanexw was, at the same time, fighting to be compensated for the land his family lost when Chaythoos was destroyed. The headline reads “Indian Seeks Cash.” The family was told they’d receive a sum for their loss, X̱ats'alanexw later told Matthews. “But they have not paid yet.”

It's clear that X̱ats'alanexw was holding conflicting truths; he had the attention of people in power, but he was also living at their behest. Still, in their conversations, there's a genuine warmth between Chief X̱ats'alanexw and Major Matthews.

“Two men, one white, one brown, sat side by side on a cottage verandah on a sunny summer's evening at Kitsilano Beach,” Matthews wrote in early October 1937. “Old friends, enjoying each other's company, and with a tray of tea and iced cake between them, watching the blue sea beyond the sandy beach of Kitsilano. It was a tranquille [sic] happy scene.”

X̱ats'alanexw is “as kindly a gentleman — and a wise one, too — as ever I knew,” Matthews writes at one point. But it can also be jarring to see how Matthews describes X̱ats'alanexw, and Indigenous people in general, at other times. The archivist, who likely fancied himself an amateur ethnographer, cannot seem to shake the romanticized, often patronizing lens with which he views his friend.

“He is an entirely different character to those Indian entertainers who are ‘show men,’ who are said to make up Indian tradition and lore to suit their audience. August is dependable,” Matthews wrote to a colleague at the Public Archives of Canada.

He goes on to describe X̱ats'alanexw as a “living link” to the Stone Age. The Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Chief countered by dubbing Matthews a “relief age man,” in reference to the many Canadians on government support at the height of the Great Depression.

Matthews says he “put down what he said in his own words the day he said it, and frequently read back to him what I had typed, and he corrected or added.” But there are moments that put his commitment to accuracy in doubt. When X̱ats'alanexw tries to correct where he was born — Chaythoos, not Sen̓áḵw — Matthews says it would be “more in keeping if he was born in Kitsilano” because of his name.

It’s true that much of the text is in the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Chief’s own words, but it’s also curated (and sometimes paraphrased) by a man — although progressive for his time — who worked for a city that had recently displaced X̱ats'alanexw and his entire community.

Major Matthews was surely a product of the (Eurocentric) society he was living in, says Rudy Reimer, a Sḵwx̱wú7mesh archeology professor at Simon Fraser University, whose ancestral name is Yumks. He keeps an original pressing of the book, gifted to him by an Elder, in his office.

But unlike other ethnological works, the book doesn’t treat Indigenous people in a clinical, dehumanizing fashion, he says. It doesn’t omit X̱ats'alanexw’s voice or his sense of humour. “With Conversations, it's front and centre.”

Sen̓áḵw returns

Amid a worsening housing crisis, the new Sen̓áḵw has become a hot-button issue among locals frustrated by a lack of community input. (Since the project will be built on reserve land, the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh can bypass municipal zoning and public consultation.) Many say they’re worried the neighbourhood can’t handle the dramatic influx of new residents.

Besides a NIMBY’s worst nightmare, Sen̓áḵw might also be one of the most tangible examples of Indigenous reconciliation in Canada.

The development will sit on a small piece of the old Kitsilano reserve. Following a long legal battle, about 10 acres in reserve land was was repatriated to the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh in 2003, along with $92.5-million. (That’s about one-eighth of its former size.)

A significant number of the units will be set aside for Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Nation members. Revenue from the development could improve the nation’s access to education, social services, health care, language, and arts and employment opportunities, according to recent research by Tiffany Kaewen Dang, a geographer whose work focuses on the use of parks as a tool of colonization. Sen̓áḵw could also be used to fund other land claims, notoriously expensive endeavours.

“Khatsahlano dreamed of being buried at Snauq,” wrote Lee Maracle in “Goodbye Snauq.” “I dream of living there.”

Maracle was born in North Vancouver, the granddaughter of Oscar-nominated actor and səlilwətaɬ Chief, Dan George. And though she came to identify as Stó:lō, she spent a lot of time with X̱ats'alanexw when she was a girl. The Chief left a mark on her, and he features heavily in “Goodbye Snauq.” Maracle wrote the story in the wake of the 2003 land claim settlement, something the narrator — who bears more than a passing resemblance to the author herself — has trouble celebrating. She mourns the old Sen̓áḵw, the one her ancestors knew. She can’t foresee the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh development that will soon transform the area.

Maracle dreamed of living at Sen̓áḵw. Soon, many Sḵwx̱wú7mesh will.

It’s a story of reclamation that Conversations with Khahtsahlano helped bring to fruition. It affirms the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Nation’s historical connection to Sen̓áḵw and the surrounding area in a way that few other books do.

That’s its power, said Syex̱wáliya, also known as Ann Whonnock, a Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Nation councillor and grandniece of X̱ats'alanexw.

“This is making us visible again,” she said. “We’re no longer invisible. I’m still here.” ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice, Municipal Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: