[Editor’s note: This is an excerpt from 'Shadows and Light: A Physician's Lens on COVID' by Dr. Heather Patterson, an emergency physician granted access by Alberta Health Services to photograph five Calgary hospitals throughout the pandemic. The pictures offer a behind-the-scenes view of the impact of the virus, from the lives of health-care workers to what patients experienced when hospitalized with COVID.]

In November 2020, during Calgary’s second COVID wave, I walked into the Foothills emergency department with my camera instead of my stethoscope.

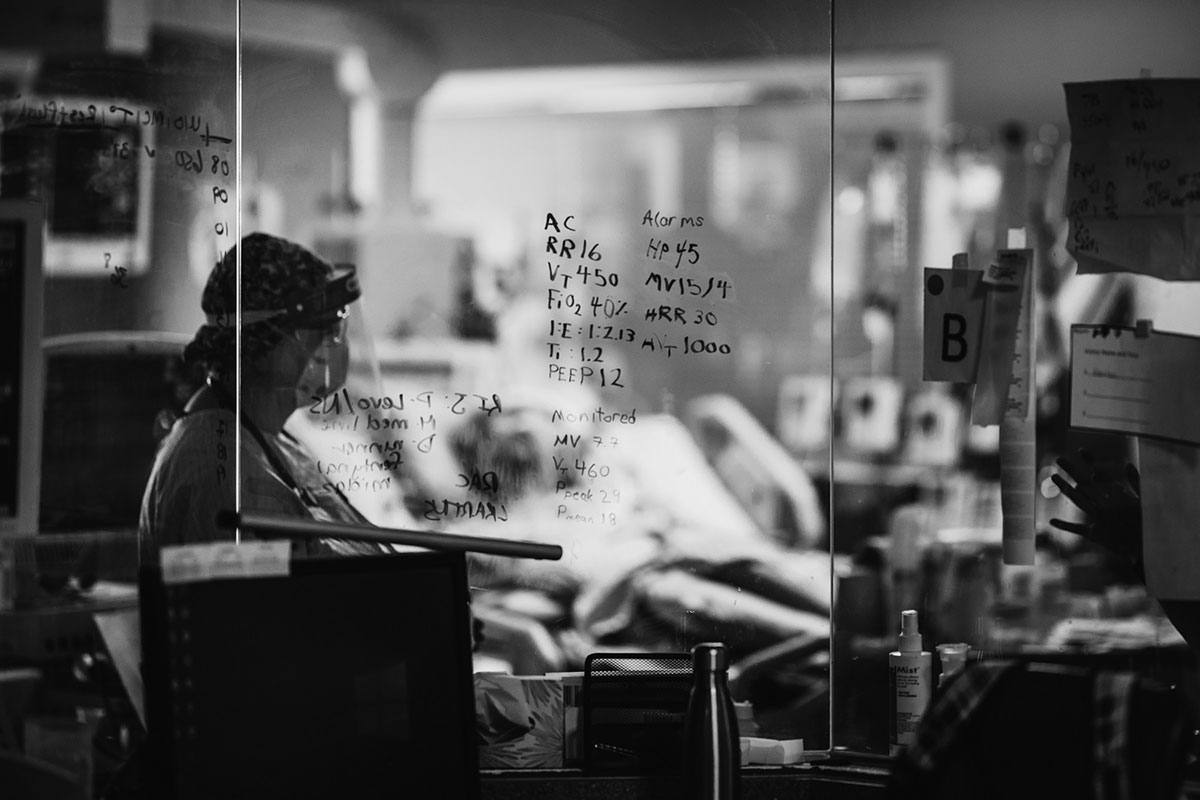

To get prepared, I’d taken courses and been mentored by university professors and internationally recognized photographers. Still, I was terrified. But the emergency department was a safe environment for me. Surrounded by supportive friends and colleagues, I had time to understand and respond to the physical and technical challenges — harsh artificial light; photographing in personal protective equipment through the layers of my face shield and goggles; the faces of the team obscured by the reflective surfaces of their own shields and goggles, with deep shadows hiding their eyes; and finding room to photograph unobtrusively in a crowded, busy space.

I worked with Alberta Health Services to address the challenges involved in photographing in the hospital and moving from the role of physician, with the core value of patient privacy, to the role of photographer, sharing images and stories of those who would otherwise remain anonymous. Ethics reviews, meetings with the privacy and legal departments, and correspondence with communications teams and Alberta Health Services leadership were encouraging, incredibly helpful and supportive.

I realized that this could act as a historic record to show how the pandemic was affecting frontline workers and citizens and generate empathy. Eight months after our first conversation, I received approval to photograph at five Calgary hospitals: Foothills Medical Centre, Rockyview General Hospital, Peter Lougheed Centre, South Health Campus and Alberta Children’s Hospital.

Day by day I became more comfortable, but nothing could have prepared me for the impact of photographing my friends and colleagues and their patients. I could see more clearly the role of each team member and the warmth and empathy they exhibited.

I am inspired by the people in these images who have given us a window into their COVID experience, often by allowing themselves to be vulnerable and exposed during their most difficult moments. And I realize the need to follow their example.

Medical culture carries a long tradition of telling ourselves and others that we are “fine,” but the pandemic offers us the chance to accelerate a much-needed change. I hope health-care workers and others in our community see glimpses of themselves in these images and stories, take time to reflect, and become curious about others’ experiences. It is time for us all to engage in discussion about how we can promote self compassion and empathy within our culture and our communities. We owe it to the people we love, to the people we care for, and to ourselves.

David speaks to his daughter before undergoing bronchoscopy, an invasive procedure to look directly at the airways in the lungs. Dr. Chip Doig, a critical-care physician, holds the phone. David did not have COVID; his respiratory symptoms came from other causes. But he was one of countless patients whose experience of illness and health care was a more isolated one because of COVID. Due to public health restrictions, he hadn’t seen his daughter or grandchildren for several months.

“Lead with your heart,” Erica Foulds tells me, as we sit for the evening at the bedside of a dying woman. She has been volunteering with the No One Dies Alone program twice a week for the past two years, bringing companionship through touch, talking, singing and reading poetry. Since 2016, this program has brought comfort to those dying in hospital without friends or family nearby. During COVID, the numbers increased because of loved ones who couldn’t travel due to public health restrictions. At least three or four patients each week had a volunteer at their bedside during the last 72 hours of their lives.

Sangarie Matengey wears full PPE, as required, to wash the floor in a patient room in the ICU. She has worked as a housekeeper for eight years — four in the ICU and four on the wards. Proud of her hard work during the pandemic, Sangarie said she looked forward to resting after her shifts and was grateful that her family remained healthy. It takes two people up to an hour to clean and decontaminate an ICU room to prepare it for the next patient.

Nash, snuggling with his parents in hospital. Too young for vaccination at nine months, he contracted COVID. We saw an increase in pediatric cases and admissions to the Alberta Children’s Hospital during the fourth wave, including children admitted to the ICU. Watching infants, children and teens suffer was heartbreaking as a parent and a physician. I desperately wanted everyone to recognize the impact on children.

Jim, a patient on the COVID ward, claps along as staff members celebrate his 62nd birthday by dancing and singing outside his isolation room. Smiles and laughter filled the room and corridor. Jim had joked that he wanted “dancing ladies” for his birthday. He didn’t realize we were paying attention.

Excerpted from 'Shadows and Light: A Physician's Lens on COVID' by Dr. Heather Patterson. Copyright © 2022 Heather Patterson. Published by Goose Lane Editions. All rights reserved. ![]()

Read more: Health, Coronavirus, Photo Essays

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: