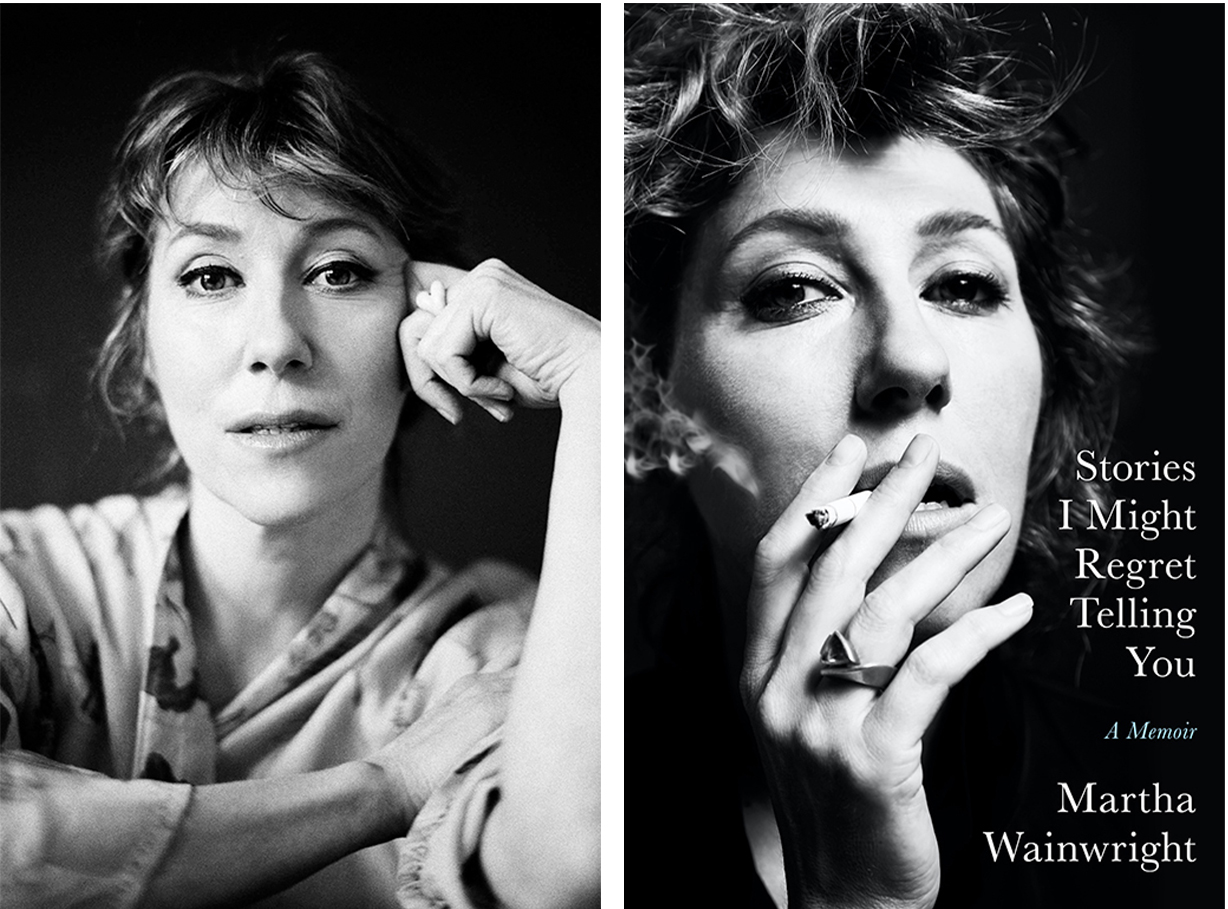

Stories I Might Regret Telling You: A Memoir

Martha Wainwright

Penguin Random House Canada (2022)

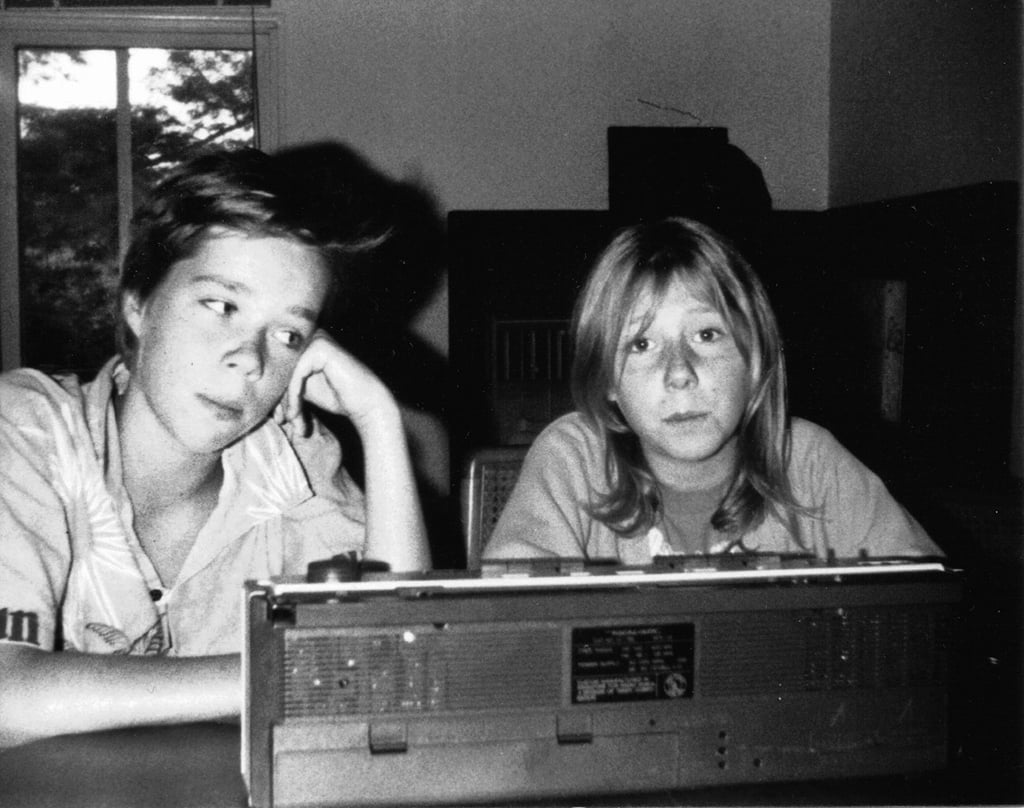

“There are lots of pictures of us caught up in the cables at the front of the stage, looking bored or half singing along in the summer heat,” singer-songwriter Martha Wainwright says about summers spent with her brother at folk festivals in her memoir, Stories I Might Regret Telling You. “These shows were work, but they were also our summer vacations and usually so laid-back, you could practically imagine a barbecue set up onstage along with some lawn chairs.”

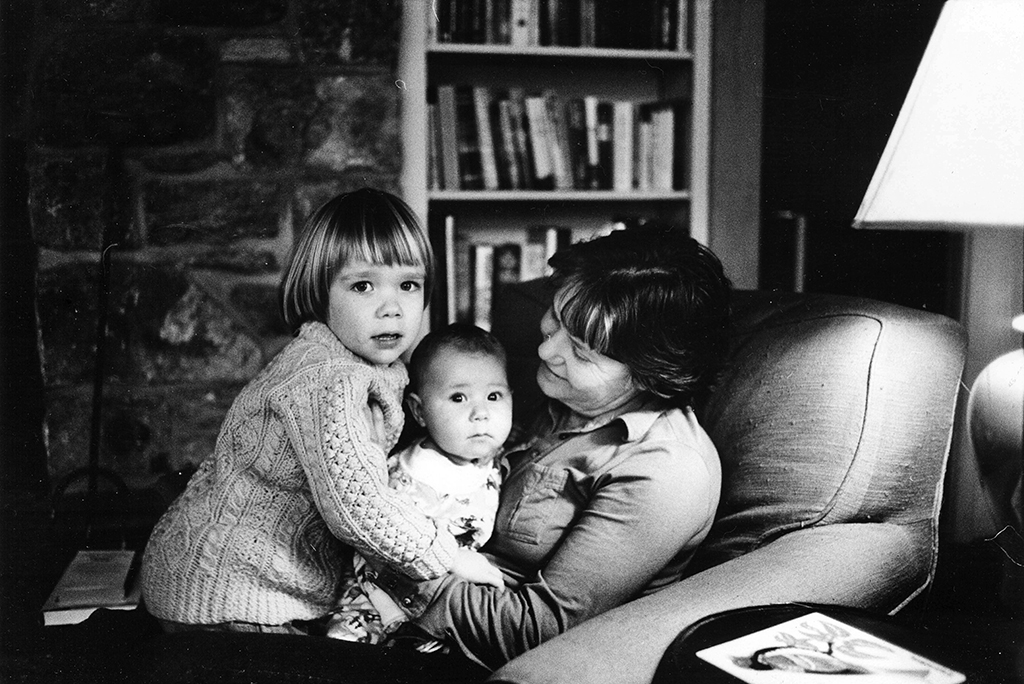

Wainwright, the daughter of singer-songwriters Loudon Wainwright III and the late Kate McGarrigle (who performed with her sister Anna), was literally raised onstage. Born in New York City in 1976, Wainwright and her brother, singer-songwriter Rufus Wainwright, were brought up mainly by their mother in Montreal.

As a teenager, Wainwright briefly lived with her father. Onstage, years later, as she recounts in her memoir, Loudon introduced an acrimonious song he’d written called “I’d Rather Be Lonely” (sample lyric: “I think that I need some space / Every day you're in my face”) as being inspired by that time together. Predictably, the younger Wainwright was devastated. “A part of me wanted to jump to my death,” she writes. “But the show must go on, so I dried my tears and… sang 'Dead Skunk' with him, looking to stress any discordant harmony that could possibly make the song more interesting.”

As that passage demonstrates, the airing of interpersonal and domestic strife in song is a family tradition. Wainwright’s first hit (from the 2005 album of the same name), the transcendentally rageful “Bloody Mother Fucking Asshole,” simultaneously eviscerates her father and sexism in the music industry.

Like her songs, Stories I Might Regret Telling You entrances readers with its candour and bite. Her narratives have their share of rock-and-roll moments with hard drugs and celebrity cameos, like Yoko Ono in a basement kitchen, “poised in the corner like a queen, [where] she would say arresting and painful things like ‘We only live to die’ in her sweet, but a little scary, Japanese-accented voice.”

Readers unfamiliar with the family’s songbook will still find themselves captivated by Wainwright’s portrayal of a family that sang together while trying to outshine one another. And anyone who’s ever lost a parent will get emotional at Wainwright’s lovingly detailed account of her mother Kate’s final days before succumbing to cancer.

When I spoke to Wainwright over the phone, she was north of Montreal inspecting a family property after a storm. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

The Tyee: Your book’s power is in its honesty. But there's also a lot of restraint in your book. How do you draw the line between honesty and oversharing?

Martha Wainwright: A lot of memoirs can afford to be tell-all, because people are at the end of their lives. But I'm right in it still, you know? Because my songs, as well as songs of my parents and Rufus, have touched on some of these subjects already in our songwriting, I felt that was a place that I could go to, that I could divulge, and that, I think, interests people. It's a family story that a lot of people will recognize and see similarities in their own family story.

I was doing a YouTube deep dive of your music and your family's music. And I saw a great Late Night with David Letterman appearance with Kate and Anna McGarrigle. While your parents are famous, they aren't Taylor Swift or Leonard Cohen-famous. Do you think that's partly the secret to the longevity of the Wainwrights and the McGarrigles?

Kate and Anna, they lived in an era where you could live in two worlds, where you could really have that kind of success. They were also on Saturday Night Live and played Carnegie Hall. But then at the same time, they didn't make a record for eight years. They were present for their children’s lives.

But it also left room for me and my brother to usurp our parents. I can be happily influenced by them, but able to go beyond that and have my own story.

So it seemed like a doable thing when Rufus and I were younger. Whereas for some friends of ours — when you're John Lennon’s son, it’s a harder road.

Well, that ties to my next question about how, in your book, you write about Rufus being part of a "sons of" club (along with Sean Lennon, and the sons of Leonard Cohen and Stephen Stills) and you feeling left out of it. You sing about sexism too in "Bloody Mother Fucking Asshole." How did you push back against sexism in the music industry?

When Rufus and I were in our 20s, we were part of that first generation of kids of stars of folk and rock and popular music. There were not a lot of girls making music and there was really never much of an example of, as a girl, of how to be. I was not only comparing myself to these other musicians, I was also vying for their sexual attention. So it's sort of a two-way thing. I wanted them to like me, but at the same time, I wanted to compete with them and be just as good if not better. The loneliness spurred on the music and the music spurred on the loneliness.

Some of the most gripping and vividly rendered passages are when you write about your mother’s death and how that intersects with the difficult premature birth of your first child, Arcangelo, while performing in London. What was it like putting yourself through this again in writing about it?

I think that is the main story of the book, and the main event in my life, up until that point. Rufus and I have been mourning our mother's death for a long time. We've been dragging it out purposely, you know, by singing her music and starting a foundation in her name to raise money for cancer research. I didn't realize this when I started, but writing about her death was freeing in many ways.

That being said, every time I've had to read that section, at a book event or when I did the audiobook, I still get quite moved and upset. And that's good too, because that means I'm not disconnected and that it's still powerful.

You write about being onstage at an early age. Is that something you're doing with your children, bringing them on the stage and performing?

One of my sons is really into music and really wants to get up on stage. My other son almost pushes away from it. And so I'm just trying to be sensitive to that and to know that they need to have their own relationship to music and their own story.

Rufus was just in Montreal and he played a show at Place des Arts. I made my youngest son watch the first half; the second half he could go into the back and watch a movie, but I wanted him to see his uncle and be challenged.

Did he love every second of it? No. But at one point he did turn over to me and say, “Rufus is a really good singer.” And I was like, “OK, my work here is done. You can go watch a movie now, I'm not gonna torture you anymore, but I do want you to recognize art and, and see your uncle and how incredible he is.”

You're also playing live music again. How's that been?

It's good. I'm careful not to book too many gigs because attendance is down everywhere. My audience also is older. They're not all ready to come back into small venues and be shoulder-to-shoulder. But I've been really fortunate. I can get in my car and play for a small audience with my guitar, get a cheque and come home.

It'll be really interesting for me to sit down after this summer after touring, in front of a computer screen or in front of a piece of paper with a pencil, and see if there's anything else to write about. I'm a little nervous. Whatever comes, it'll take time because you know, it's really not easy to write. You gotta weigh every word and every sentence. You want to connect. So that's really what I'm curious to see. ![]()

Read more: Music

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: