In the new documentary about Bruce Mau, the designer provides an analogy about how information on the state of the world is often provided. Using the metaphor of a book, he explains that the first few pages are all screaming headlines about war, famine, violence, tragedy, etc. But go a bit deeper and there is a wealth of stories about people collaborating, co-operating and working together to make things better.

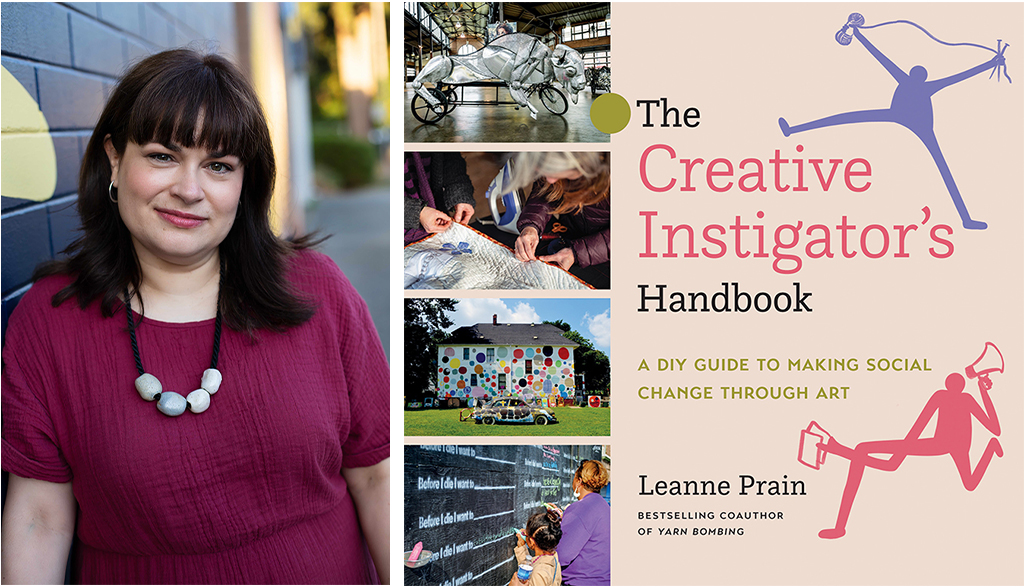

As he says these stories actually make up the bulk of the global narrative, although we rarely hear or read about them. Many of them are included in Vancouver designer and writer Leanne Prain’s new book, The Creative Instigators Handbook: A DIY Guide to Making Social Change Through Art.

Unlike superstar designers like Mau, the people profiled in Prain’s down-to-earth guide to changing the world are chugging along, creating, making and organizing on a smaller scale. But even the most modest action and events can manifest big impact.

Prain is a veteran of the local arts community. In 2009, she co-authored Yarn Bombing: The Art of Crochet and Knit Graffiti, recently re-released in a 10th anniversary edition. She also wrote 2014’s Strange Material: Storytelling Through Textiles, two of her four books published by Vancouver’s Arsenal Pulp Press. Instigators expands upon some of ideas explored in her earlier work, looking at different creative practices across North America, from Vancouver to Brooklyn.

As an artist and “craftivist” herself, Prain has unique insight into the pains and joys of making things in the public realm. The democratization of art is one central tenet, but another is simply to try stuff: whether it succeeds wildly or falls flat, no matter. Just keep going! This cheerfully balanced approach sets the tone for the book, equal parts practical and inspirational.

Examples of DIY creativity included in Instigators range from the basic (posters, cool buttons, quilts) to the wildly elaborate and long-term (permanent gallery spaces, an enormous model of the moon!).

The book is organized into a series of case studies and interviews with artists, activists, teachers, community organizers and ordinary folks — people who had an idea or saw a need and decided to do something about it. Interspersed between these conversations are sections devoted to helping would-be instigators plan for and navigate the complexities of event production. The advice ranges from simple things (don’t forget the duct tape and plastic bags!) to figuring out how to extricate oneself from a creative partnership that has gone awry.

When redesigning the world, it is critical to engage with other like-minded folks. The importance of community and of getting people involved is emphasized throughout. A good number of these hardworking creatives are right here in this city of ours.

The creation of the Alley-Oop is only one example. Located in Vancouver’s downtown core, the space offers local Instagrammers, b-ballers, hanger-outers and anyone who likes bright colours and fun stuff a place to do their thing. Melissa Higgs of the HCMA Architecture + Design firm who championed the idea explained in an interview. “In Vancouver, we don’t have enough places for people to gather in our city. It’s not reasonable to think we can purchase more park space, because land costs are so high. Laneways are just an obvious way to go about finding public space.”

With the support from the City of Vancouver and the Downtown Vancouver Business Improvement Association, the project came into being, sparking similar innovative ideas throughout the city.

Among the more than 20 folks interviewed in the book, some commonalities occur across the different disciplines and projects. But beneath the practical stuff is a more radical edge that argues for taking art off its pedestal and setting it loose in the streets and alleyways, the parks, the backyards and the school grounds. It is profoundly anti-elitist position, which is a great and glorious thing.

Prain makes the case that maintaining the old divisions between the museum and gallery systems and more grassroots stuff serves an older, and perhaps outdated paradigm that renders art as precious, inaccessible and expensive.

In the book’s opening section called “Art Snobbery Only Helps Art Snobs,” she states her position outright.

“I believe that art and design can belong to everyone. When art is categorized into high art versus pop culture, professional versus amateur, or outsider versus accomplished, we exclude some people and their voices. But when treated responsibly, creativity can be our common language. It enables us to exercise our dark humour and those sides of ourselves that we don’t always allow to surface. It makes us meet our truths. It lets us show each other who we are without having to use words that we are scared to speak. I believe that creativity opens the door to making just about anything possible.”

Happenstance and happy accident play a key role in how some of the instigators came to discover their respective projects. Vancouver-based poet Kevin Spenst, for example, had the pandemic to thank for leading him to offer open-air readings in alternative locations across the city.

In other instances, projects were a direct reaction to larger social and political events. Aram Han Sifuentes started a protest banner-lending library after the 2016 U.S. election. “Banners are a way for me to resist what is happening in the United States and in the world. It is a way to put my voice out there and not stay silent.”

Diane Weymour was also inspired by the utterances of one Donald Trump. Her Tiny Pricks Project emblazoned the former president’s bon mots in stitched form. As she explains in an interview with Prain: “Tiny Pricks already had the tagline, ‘Desperate Times, Creative Measures’ before COVID-19, but I had no idea how true this would become!” The initiative is another example of good things coming out of bad happenings, but it also offered a way to speak the truth in a tangible, physical fashion.

“The high stakes of the Trump presidency brought a further need for this project,” Weymour goes on to say. “There is a sense of urgency to document our habits, feelings, and how we’ve lived. With everyone glued to the news cycle, the project provided an essential outlet to counterbalance feelings of helplessness.”

From tiny pricks to the massive moon, the projects detailed in Instigators run the gamut in both size and complexity. Vancouver’s Chris Bentzen and Jim Hoehnle of Hot One Inch Action offered participants the opportunity to go button-mad at different events, where people could purchase, swap and haggle over the artist-made buttons. The idea originated in 2004, with 50 different artists creating a one-inch button, each containing a piece of original work.

On the other end of the size scale is Luke Jerram’s Museum of the Moon. Creating an accurate model of the lunar surface required a little help from NASA. The orb, measuring some seven metres in diameter, is impressive enough, but with every iteration of the work as it toured the experience differed, depending on the music, the settings and the people involved.

Whatever and wherever the opportunities present themselves, busy humans are getting busy making art. The vehicles may vary, but the intent remains the same whether it’s a miniature library, a voting booth or a kitted-up airstream trailer, traversing the continent, bringing cool literary forms to communities across Canada and the U.S.

The Projet Mobilivre-Bookmobile Project toured North America, offering a selection of zines, books and other fun stuff. Prain and a friend visited the mobile literary extravaganza on wheels during its stop at Emily Carr University.

As the two of the co-founders Courtney Dailey and Onya Hogan-Finlay explain, the Bookmobile was a product of the pre-internet era, when access to indie publications actually required physical media. But another, more critical aspect of the project was opening up discussions about different ideas.

Dailey explains in an interview in Instigators.

“We had also come to it from DIY activist backgrounds. Those values stood in pretty sharp contrast to this new-to-us rarified artist-book world. We were interested in challenging the preciousness of artist books that were in the special collections of libraries. Limited-edition and one-of-a-kind artist books that were not mass distributed objects, like zines or comic books. Zines were communication devices; they were accessible. We were motivated to make printed multiples to address issues and subject matter that no one else was talking about.”

The right time to evolve or end a project forms another through line in the book. Everything has a life span and when a project has run its course, it’s okay to hang it up. Some of the projects profiled in the book have ended, while others have taken on different shapes and new iterations. But this too is a good and fruitful thing, creating a layer of creative humus from which new ideas can sprout.

If you’re looking for ideas, inspiration or hard-gleaned wisdom, Instigators is an excellent guide. More importantly, it’s a heartening reminder that a great many people are out there, doing good, working hard to handmake a better world. ![]()

Read more: Art

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: