- The Devil’s Trick: How Canada Fought the Vietnam War

- Alfred A. Knopf Canada (2021)

After half a century, the Vietnam War is ancient history to many Canadians — and someone’s else’s history, at that. But Canada was entangled in Vietnam for a decade before the war; we tried and failed to prevent it, and our experience in the war shaped our response to later wars and the refugees they generated.

Historian John Boyko is a good researcher and an even better writer. He breaks his book into six chapters, each built around a person who typifies an aspect of Canadian involvement in Vietnam. Sherwood Lett was a brilliant lawyer and veteran who led our contingent on the International Control Commission in the 1950s. Blair Seaborn was a career diplomat whose mission to the North Vietnamese Communists could have ended the war before it began.

Claire Culhane worked in Vietnam and then waged a one-woman resistance campaign against the war. Joe Erickson was a young American who came here rather than fight; Doug Carey was a Canadian who joined the U.S. Marines. And Rebecca Trinh was a Vietnamese refugee who survived horrors to reach safety here. All six emerge as memorable people trying to deal with complex and ambiguous political and moral issues.

Canada itself was similarly ambiguous about the war. Ottawa in the 1950s was reluctant to get involved in Vietnam right from the start, but wanted to please the Americans. While most of us disapproved of the war, we prospered selling them weapons, napalm and Agent Orange — a defoliant that caused untold environmental and genetic damage to Vietnam and its people, as well as to Canadians and Americans who were exposed to it.

Sherwood Lett and his team were supposed to help supervise an orderly transition to a reunited Vietnam under a democratically elected government; in reality, the Communists and anti-communists continued their civil war and used the ICC to score propaganda points against each other. It was soon clear that the U.S. had no intention of allowing an election that Ho Chi Minh was sure to win. Lett managed to defuse some dangerous situations, but he realized the commission was only a screen, behind which the real players were preparing for war.

Then the Americans asked Canada to carry an offer to Hanoi: keep Vietnam divided in two, leave the South alone, and U.S. economic aid would go to the North. Otherwise, the U.S. would attack. Blair Seaborn, a career diplomat, delivered the message and brought back a counter-offer: leave the country. Then let Vietnam sort out its own problems and reunify as a neutral nation. The Americans didn’t bother to listen; Seaborn’s mission had been an afterthought, not a serious effort to stave off war.

Claire Culhane was a hospital administrator who applied for a job in a new Canadian-built hospital in South Vietnam. She was also so radical that she’d quit the Canadian Communist Party as a talk shop, but she got the Vietnam job anyway, and joined a team that provided much-needed service in the hospital’s region. But the hospital had been created as a propaganda showpiece, and Ottawa quickly replaced the original team with people less eager to help the Vietnamese.

A ‘scum community’

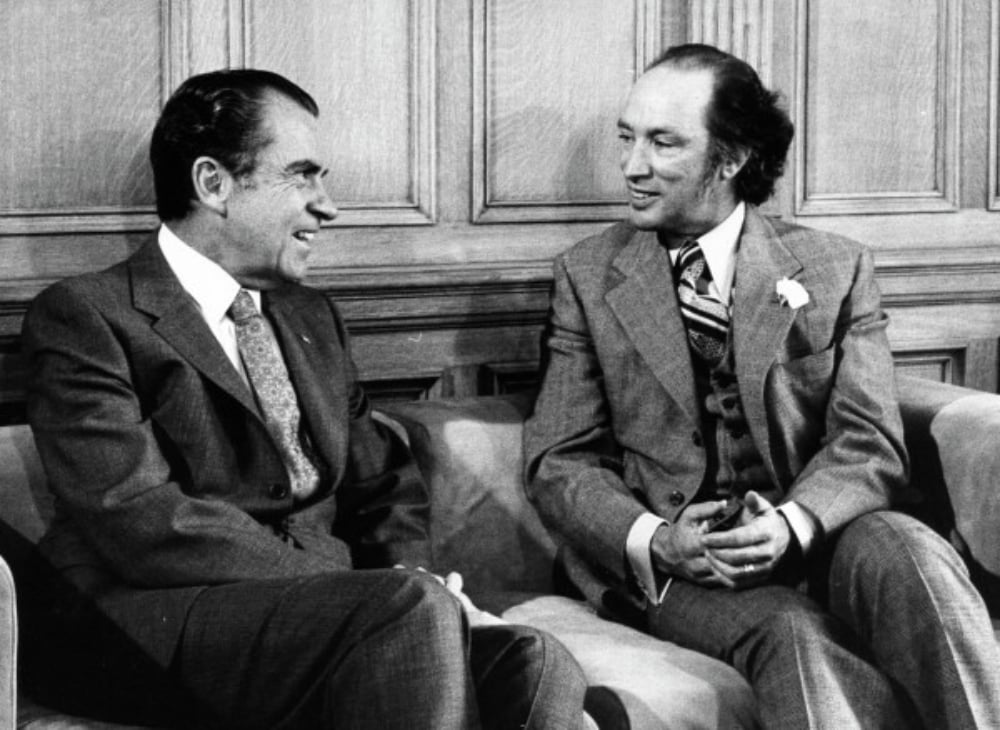

Culhane returned to Canada and became a serious nuisance to the Pierre Trudeau government. She called out Trudeau’s hypocrisy in supporting the British arms embargo against apartheid South Africa while flogging Canadian weapons sales to the U.S. She caused a ruckus in Parliament during question period. She had several personal exchanges with Trudeau, in one of which he told her: “You have no idea of the pressure I am under.” After all, 150,000 Canadian jobs involved producing arms for the U.S.

Boyko describes how Joe Erickson, a Minnesota farmer’s son, wrestled with the moral issues of the Vietnam War and finally decided to head for Canada with his wife. They arrived in 1968 as landed immigrants (very easy, in those days, if you were white and college-educated) and settled down in Winnipeg. Like many immigrants, they made friends with their fellow-nationals and worried about surveillance from the authorities in the old country.

Erickson was one of over 25,000 war resisters (including their wives, girlfriends, and sometimes mothers) who arrived between 1965 and 1970. They added to the cultural and political ferment of late-'60s Canada and drew criticism from what Boyko calls “Old Canada:” “British-oriented, white, patriarchal.” Vancouver Mayor Tom (“Terrific”) Campbell described them as part of a “scum community.”

Resisting the resisters

Canadian universities saw some resistance to the resisters as well: as Canadian post-secondary expanded dramatically, it recruited many Americans including draft dodgers and deserters. This triggered a spate of Canadian nationalism among some academics, enhanced by a general dislike of the Vietnam War. It would die down as more Canadians completed master’s and PhD’s and established their own careers.

Many years later, Joe Erickson returned to Minnesota for a high school reunion and was interrogated at the border. He then learned that the FBI had harassed his family, trying to get his parents to persuade him to return home; his family did nothing of the sort, and didn’t tell Joe either.

Meanwhile Doug Carey, a U.S.-born Canadian, headed south in 1965 to join the Marines. He was technically in violation of a 1930s law intended to keep Canadians from joining the International Brigades fighting in the Spanish Civil War. But Ottawa didn’t enforce it, and thousands of young men followed Carey. Their motives were mixed: some were anti-communist, some had family traditions of military service and some just wanted to see what a real war was like.

After serving two tours in Vietnam, Carey was shipped home with Japanese encephalitis, contracted from a mosquito bite. He recovered, but was baffled by his own short temper, nightmares and flashbacks.

It’s never over

Not until 1980 was post-traumatic stress disorder recognized and named. A U.S. Army researcher found that “40.2 per cent of American and 65.9 per cent of Canadian vets suffered symptoms of PTSD during their service or after returning home.”

Why so many more Canadians? According to Boyko, “Fewer Canadian doctors and psychologists were properly trained to diagnose or treat PTSD and there was no government funding for treatment.” He tells us Carey eventually got help in the U.S., funded by the Americans, but is still haunted by the war.

Rebecca Trinh and her husband Sam were ethnic-Chinese Vietnamese who found themselves persecuted in 1978 when reunified Vietnam fought a brief war with China. They hoped to join Sam’s sisters in Alberta, but the only way to get there now was to become boat people — refugees crammed in decrepit ships in search of a haven. They and their children endured hunger, sickness and pirate attacks before finally reaching Malaysia and months of waiting and hoping Canada would accept them.

It wasn’t certain. Polls showed half of Canadians didn’t want any refugees at all, but Flora MacDonald, secretary of state for external affairs in the short-lived Joe Clark Tory government, shocked the country and shamed the world by declaring we would take 50,000 of them by 1980.

Canadian immigration officers flew to the refugee camps and somehow managed to interview, screen and approve thousands, including the Trinh family. Despite some racist backlash the Trudeau Liberals, now back in power, increased the Indochinese immigrant total to 60,000. Like every big wave of immigrants, the Vietnamese, Laotians and Cambodians settled in, adjusted and became part of the country.

We like to remember our best achievements, not our worst, so we prefer to remember Claire Culhane saving lives in a hospital never intended to be more than a showpiece. We prefer to remember serving as a haven for draft dodgers, and forget the officials who despised them.

We certainly don’t want to remember Agent Orange, but Pierre Trudeau needed the jobs it created, just as his son would need the jobs created by SNC-Lavalin, and Stephen Harper remains proud of the deal he made with the Saudis for armoured vehicles.

And while we like to think of ourselves as welcoming refugees, the truth is many of us didn’t like them then and many of us don’t like them now.

Nevertheless, however conflicted Canada was about Vietnam, we eventually did more good than harm through our involvement. Perhaps we will be able to say the same thing, some day, about our involvement in Afghanistan. ![]()

Read more: Federal Politics, Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: