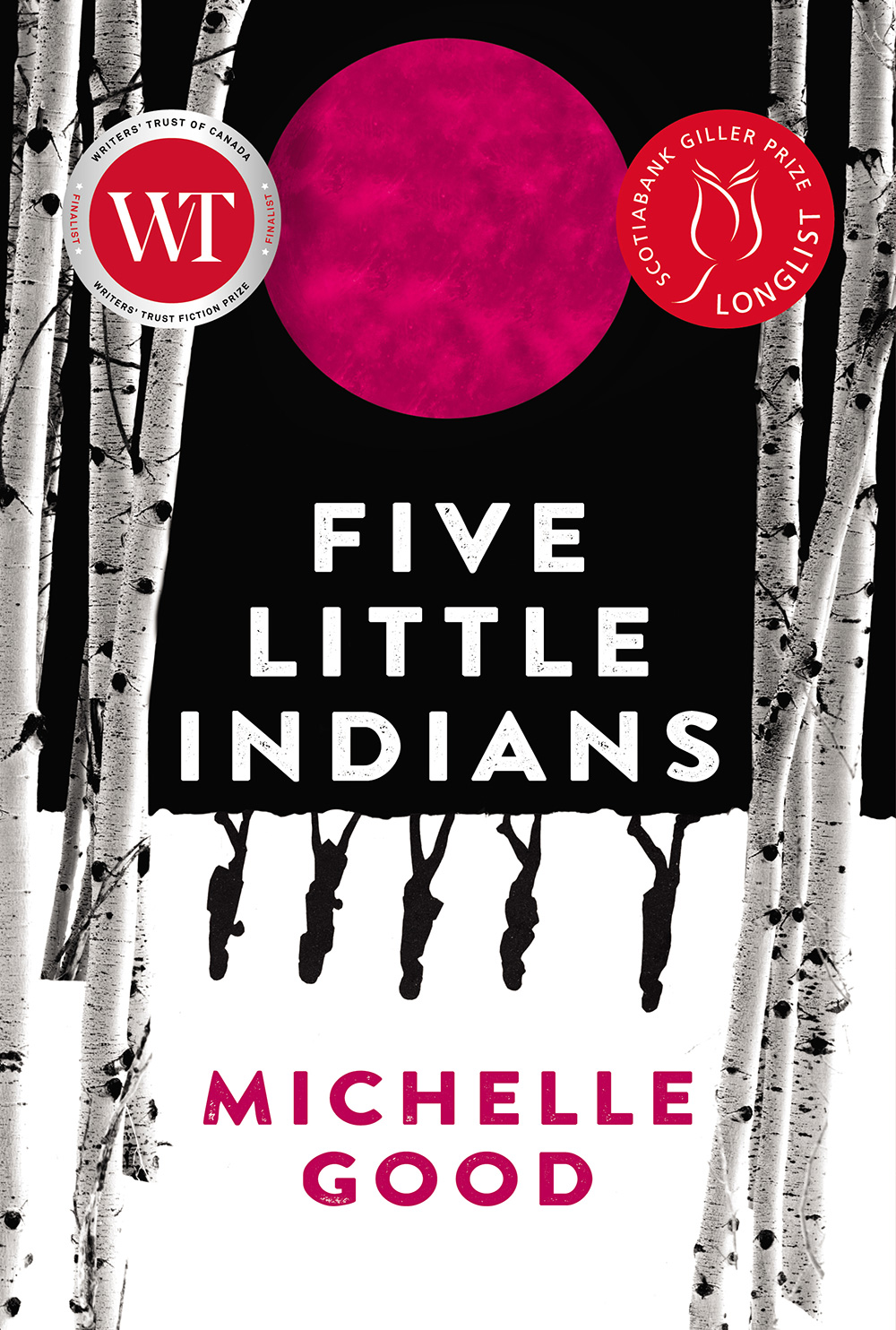

Cree writer and lifelong activist Michelle Good is busy with the phenomenal response to her bestselling first novel, Five Little Indians.

“My reading life is a victim of my own success,” says Good, who has not had much time to sit down with a good book lately. Instead, she’s been inundated with interview requests (like mine!) after her debut novel was nominated for the Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction, the Amazon Canada First Novel Award and the Kobo Emerging Writer Prize — all in the same day in early May. The book was also, last year, a finalist for the 2020 Atwood Gibson Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize.

Good, a member of the Red Pheasant First Nation in Treaty 6 territory, was born in Kitimat, B.C., in 1956. “There wasn’t even a road into town at that point,” she recalls. Her mother and grandmother, along with many aunts and uncles, attended residential school, and Good was profoundly shaped by their impact.

“I am an intergenerational survivor,” she says. “I think people tend to say that if you didn’t go to a school, you’re not a survivor. But I am a survivor. To say that I’m not is to suggest that my mother’s experience was not reflected in our relationship, or in the challenges that she faced, the anxiety and feelings of inferiority that she faced, that we all witnessed as children. It’s different than attending a school, but it is a lived experience.”

That experience led her to activism; she began working in Indigenous organizations at age 18 and spent decades supporting and advocating for other survivors. At 43, she obtained a law degree from UBC to further her work. But writing was always a passion, and at 54 she enrolled in UBC’s creative writing MFA program and began crafting Five Little Indians.

“I’d been threatening to write a book about all of this sort of stuff for a long time, and I thought that I better get down to it if I expected it to, you know, come to fruition before I die,” she says. “The clock was ticking, let’s put it that way.”

In 2018, she received a contract for Five Little Indians as the winner of the HarperCollins Canada/UBC Prize for Best New Fiction.

Good expected that the book would be well-received by a niche audience of readers like social scientists, survivors of residential schools and activists like herself who have advocated for survivors. The book’s success has massively surpassed her expectations.

“The broad audience that has picked up this book… it’s literally beyond my wildest imagination,” she says.

Between media requests and working on her forthcoming second novel, Good found time to answer a few questions about her favourite books. This interview has been edited for clarity and condensed.

What are you excited to read these days?

I’m a big fan of historical fiction. And my favourite author of all time is Louise Erdrich. I think she does the historical braided novel like nobody else. I have her latest book, The Night Watchman, waiting for a moment when I can have some time to just read it comfortably without having to set it aside to do a lot of other things.

What else have you enjoyed lately?

I loved Empire of Wild [by Cherie Dimaline], I loved Moon of the Crusted Snow [by Waubgeshig Rice]. I like a lot of American Indigenous authors: Gerald Vizenor, N. Scott Momaday, Winona LaDuke. There was an earlier presence of Indigenous writers in the U.S. than there was in Canada, though the border doesn’t really exist for Indigenous peoples.

What are your favourite books, by Indigenous authors and others?

Everything by Louise Erdrich, I love them all. The Grass Dancer by Susan Power; Halfbreed by Maria Campbell, Cannery Row by John Steinbeck; Swamp Angel, Love and Salt Water and The Innocent Traveller by Ethel Wilson; The Diviners and A Jest of God by Margaret Laurence; everything by Alice Munro; Blue Ravens by Gerald Vizenor; The Ancient Child and House Made of Dawn by N. Scott Momaday; Gilead and Lila by Marilynne Robinson; Beloved and The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison; The Color Purple by Alice Walker; Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys; Sweetland by Michael Crummey; The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov. Good grief, the list could go on and on!

You’re working on your second novel. What’s it about?

It’s a historical novel, based loosely on the life of my great-grandmother, who was born in 1856. She was a young woman at the time of the Northwest Resistance, though I don’t call it that. And she would have been there, because she was Chief Big Bear’s niece. She was with Big Bear’s band when the North-West Mounted Police hounded them across the border, into Montana.

And it’s the story of clearing the Plains to allow for settler dominance in the Prairies, through the eyes of an Indigenous woman who had never even seen a non-Indigenous person until she was in her late teens or possibly early 20s. So a woman who lived a significant part of her life without that ugly influence, without the things she would experience later in her life.

Are you drawing on family stories that you were told?

Some of them, but she was long deceased before I was born. It’s really an exercise in imagination, placing this person. It’s easy to make her my character because there’s a blood relation, but it is going to be largely fictionalized. It’s a contemplation of that time and what was going on then, as told through her voice. There’s a lot of historical research involved in this one.

Are you a writer who can read other people’s books while writing?

I absolutely read fiction while I’m writing. Writing is like anything else; you have ebbs and flows. You have times when you’re feeling prolific and your story is finding the page comfortably. And then there’s times when you need to be thinking and working on it in a different way than actually putting words on the page. And I find that reading really, really supports that sort of subconscious thinking about how you’re going to present your story. I actually love reading while I’m writing.

What book do you give most often as a gift?

Well, if I give a book to somebody it’s going to be unique to that person. So I wouldn’t say that there’s one in particular. But one book that I give to any writer that’s looking for assistance with the craft is Winter in the Blood by James Welch. That is a phenomenal work, just absolutely phenomenal. I used to refer to it as my style bible.

Were you a big reader as a child?

Oh yes. And my parents were both avid readers, and some of my fondest childhood memories are of my father reading to us. I would almost say I was born reading.

What did your father read to you?

Oh, well, that’s a long time ago! I’ll be 65 soon. But one of the things he read for certain was the work of Robert Service. My father actually really enjoyed the classics, but he also enjoyed the vividness of Robert Service’s work. So there we are, these little toddlers listening to “The Cremation of Sam McGee.” That was quite a formative experience.

Was there a particular book or author who made you want to be a writer?

I always wanted to be a writer from pretty much my earliest recollections as a child. I was that funny little kid with a journal under her arm. And writing has been this enormous part of my life, although not publishing until now.

I’m curious, why didn’t you pursue that path of publishing your writing until recently?

Because I had obligations. My life was dedicated to the work of Indigenous activism. And I’m fortunate that my life opened up in a way that I could return to writing and realize that dream later.

Do you see your writing as a continuation of your activism?

Absolutely.

There are so many Indigenous authors who are bringing their experiences and realities to their work, and being widely read by all kinds of readers. What do you think is behind that interest?

What’s happening is we fought our way into the literary world. We fought our way into the literary landscape. When I was a very young woman in my teens, there were very few if any Indigenous authors in Canada that were being published. We had Maria Campbell, and a bit later we had Jeannette Armstrong. There were those early trailblazers, but it was a phenomenal thing that they would be received by the publishing world.

And there are Indigenous people now who are not simply struggling to survive, that can envision having meaningful careers. And one of them, of course, is writing. So many people are driven to write the stories that will really clarify what Indigenous reality is. I think that’s what many of these writers like Cherie Dimaline, Eden Robinson and Waubgeshig Rice — they’re really picking up the mantle, if you will, of furthering storytelling from an Indigenous reality. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: