On what would have been the centennial birthday year of Haida artist Bill Reid, the gallery that bears his name was set for a massive party, complete with a chocolate cake totem pole.

While the global pandemic may have curtailed the cake, the Bill Reid Gallery of Northwest Coast Art in Vancouver was determined to carry on with the celebrations.

The gallery is reopening with a new exhibition To Speak with a Golden Voice, a look at Reid’s extraordinary work and impact.

The show features a selection of rarely seen pieces, many of them on loan from private collections, as well as newly commissioned work from Haida artist Cori Savard and musician Kinnie Starr.

Guest curator Gwaai Edenshaw, who lived with Reid as a teenager and is considered to be Reid’s last apprentice, wanted the exhibition to feature a more personal side of the artist.

Edenshaw says part of the impetus for the show wasn’t simply to celebrate the anniversary, but to share memories, offering a more intimate understanding of Reid, who died in 1998.

This is evident in the drawings and sculptures that introduce the show. When Parkinson’s disease had robbed Reid of control and a steady hand, he kept working.

These drawings and sculptures, comprised of marks that the artist built up over time, carry with them a softness of line as well as steely intent. As Edenshaw explains, “He made his sickness work for him.”

This kind of openness to process gives the exhibition a humble quality that’s bolstered by comfy chairs where visitors can sit and listen to recordings of Reid speaking, a wall of family photographs, and a recreation of Reid’s studio on Granville Island.

Process was central to Reid, as demonstrated by the wealth of objects and tools on display: casting moulds, miniature maquettes, pens, paintbrushes and objects like an extended pen that allowed Reid to sign prints.

The artist’s puckish sense of humour is also central to the show. In the recreation of his studio, there is a wooden door with a plaque entitled "Native Washroom," emblazoned with drawings and the artist’s signature.

It’s both a statement on surrealist found objects (i.e., Marcel Duchamp’s R. Mutt urinal) as well as inside joke about the fact that when he first rented the studio, it didn’t have a bathroom. Out of this chaos came creation.

Masterworks like Chief of the Undersea World, The Spirit of Haida Gwaii and Raven and the First Men are so recognizable that it’s difficult to understand what a change they first represented to the perception of Indigenous art.

To Speak with a Golden Voice strips away this degree of over-familiarity to offer a new look at Reid’s life and work. Four distinct sections — Voice, Process, Lineage and Legacy — draw lines between the different periods of his life, uncovering sometimes little-known connections.

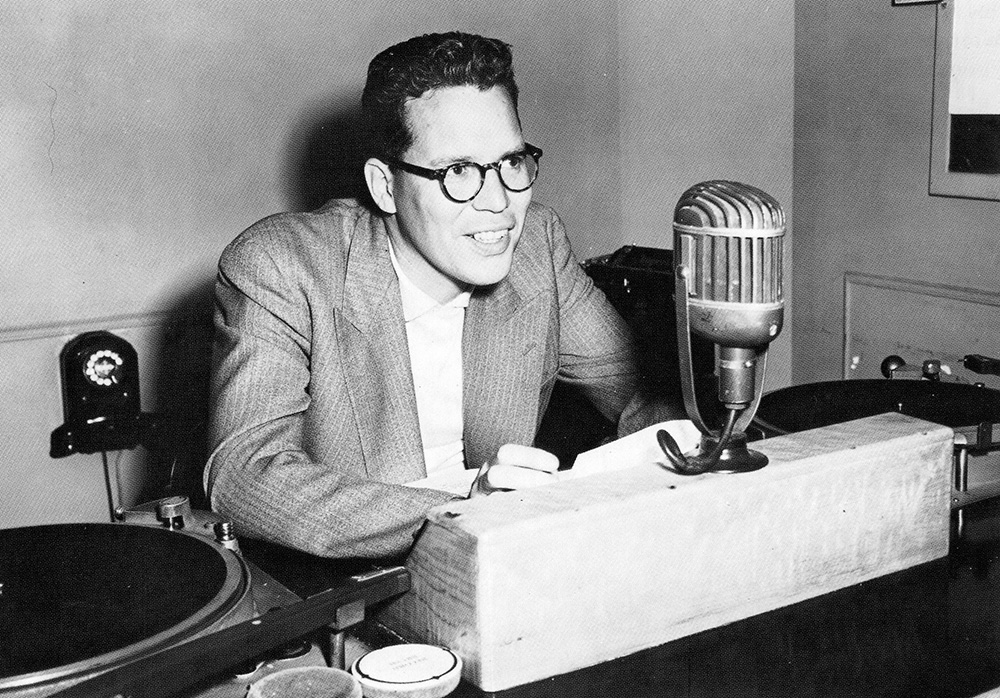

The title of the show stems from Reid’s early career as a CBC radio announcer, when he was given the name Kihlguulins (golden voice), one of the many Haida names that he carried through his life. It also provides the show with a curatorial ethos, reflecting the artist’s ability to speak to different communities and generations over time and distance.

Reid’s impact was so great that Edenshaw and co-curator Beth Carter were challenged in limiting the number of artists in the show. As Edenshaw notes in his exhibition introduction: “Just about every Northwest Coast artist working today has a connection or link to Reid.” But Reid was, by his own admission, something of an unlikely saviour of Haida art.

Raised in Victoria, his mother Sophie Gladstone Reid rarely talked about her Indigenous heritage. It wasn’t until Reid was in his thirties that he began carving large-scale totems for a project at the University of British Columbia.

Before this, Reid had worked primarily on a smaller scale, creating Haida designs in gold, silver and platinum jewelry. But after a trip to Haida Gwaii in 1954, where he discovered the work of his great-great-uncle Charles Edenshaw, the artist took a different path.

Reid is not without controversy, although the show avoids most of the issues that have dogged his career. Ambitious, driven and by many accounts something of an egomaniac, Reid still managed to bring global recognition to Haida art through his savvy understanding of the media, as well as ability to charm wealthy donors and collectors.

His behaviour with other artists, including many of those who worked on his most seminal pieces and who weren’t always credited for their contributions, wasn’t as clear cut. Other thornier issues around authenticity have surfaced over the years, including allegations that as his Parkinson’s advanced Reid was forced to rely heavily on other artists to do the physical labour of creating work.

Master artists employing apprentices has been around since the Renaissance, but contemporary artists using assistants to do the majority of creative labour has been cause for some debate.

A 1979 NFB documentary about the Dogfish totem-pole raising in Skidegate features the artist in reflective mode, talking about what his presence means to the people in the community. As he admits in the film, he sees himself as something of a disruption.

Gwaii Edenshaw’s father Guujaaw (Gary Edenshaw), who was a key part of the pole’s construction, is pictured working alongside Reid. But when Reid attempted to buy property in the area, the community denied his request.

Haida artist Robert Davidson, who credits Reid with teaching him the mastery of his craft, also had a complex relationship with the older artist. When Davidson was carving argillite sculptures at Eaton’s Department Store in Vancouver, Reid paid a visit.

The moment is recounted in the documentary Haida Modern, and as Davidson tells it, it was Reid’s voice booming “Hello! I’m Bill Reid!” that immediately got his attention. Although Reid claimed the lion’s share of credit for the rebirth of Haida culture, there were a number of artists working at the time, including Davidson himself.

Still, the impact of what Reid achieved is impossible to deny, and with his larger-than-life personality as well as access to a broad platform, he was able to introduce Haida art to a global audience.

This impact continues to ripple out, influencing younger artists. As the show’s co-curator Carter explains, it was important to include women artists in the show, and Kinnie Starr and Cori Savard were a natural fit.

The Voice section of the exhibition combines Reid’s own voice filtered through Kinnie Starr’s audio installation to make viewers feel that Reid is whispering to them as they move through the exhibition. Guest curator Edenshaw worked with Starr to create wooden masks that act as amplifiers for the sound.

As Reid was fond of saying, “Joy is a well-made object, equalled only by the joy of making it.” There is great joy in this show, emblazoned in large-scale work like Mythic Messengers and in exquisite gold pendants, bracelets and even wall sconces.

In connection with the exhibition, the gallery will publish a catalogue with essays from Edenshaw, Nika Collison and Reid’s wife Martine. Smaller scale parties are planned for Aug. 15 and 16, with demonstrations, tours and interviews.

'To Speak with a Golden Voice' runs from July 16 to April 11, 2021. The gallery is observing the recommended provincial and safety guidelines, including limiting the number of visitors, as well as offering sanitizer stations throughout the gallery and frequent cleaning of high-touch surfaces. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Art

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: