Marina Dodis didn’t have far to go to make her documentary short The Return.

The Still Creek salmon run was only a few blocks from her house in East Vancouver. When Dodis heard a CBC news story about the reappearance of salmon in the heart of her neighbourhood, she jumped on her bike and rode over to check it out.

The filmmaker was surprised to see wild salmon in the midst of such a densely urban environment, surrounded by pavement, transit lines and big box stores like Canadian Tire. “It was miraculous,” she says.

She wasn’t alone in this revelation. Many people had worked hard to make the return happen. “Here were all these people falling in love with fish.”

Although “salmon aren’t the cuddliest of creatures,” Dodis says, people seemed innately drawn to them. Maybe because of the inherent drama of their journey from the open ocean back to the tiny streams where they first came into being. It’s a Homeric story filled with life, death, sex and the longing for home. “It just resonates with people.”

Documentary audiences and fish fans can share this experience when The Return screens at the DOXA Documentary Film Festival, which starts today.

“Forty-five years ago, Still Creek was probably the most polluted waterway in the Lower Mainland,” an interviewee in the film explains. Sewage, industrial pollution, rusty bed springs and other assorted junk had made the creek little more than a garbage dump, inaccessible and degraded with decades of human trash. The salmon run was once declared dead.

Still Creek flows through major portions of Burnaby, meandering through heavily industrialized areas before turning northwest into Vancouver. A particularly pretty stretch runs alongside the Renfrew Park Community Centre at 22nd Avenue. It stands in for many other polluted waterways in the city, writer J.B. MacKinnon explains in the film, noting there are “120 creeks in Vancouver that have been covered in pavement.”

Bringing Still Creek back to something like it once was took decades of hard, often mucky work, carried out by local people who still remembered when salmon had been a part of this place. As the creek was cleared, greenery and plants were added to offer shelter, creating a more conducive environment for the fish.

Biologist Mike Pearson’s work with habitat restoration put him right where the action was, knee-deep in streams to make certain the fish have a fighting chance. Stoney Creek (the largest tributary of the Brunette River) with its cool well-shaded pools is a real refuge for fish, he says. “The last couple of years, there’s been well over a thousand chum salmon come up through here.”

The Still Creek/Brunette watershed was once the richest salmon bearing area in the Lower Mainland, with seven different species spawning in the streams and tributaries. Morgan Guerin, Aboriginal fisheries officer for the Musqueam First Nation, describes the importance of the salmon to Indigenous people: “It’s one of our genesis points.”

With the help of community stewards and individuals working over the course of decades to re-establish habitat, salmon are once again spawning in ancestral creeks. John Templeton, president of the Stoney Creek Environment Committee, is one such frontline worker.

As Templeton says, “I used to look into this beautiful crystal-clear water with beautiful gravel and wonder: why are there no salmon?” He laboured for over 16 years to make a better home for the fish, clearing debris and making a place for them to reproduce.

With more than 200,000 people in the watershed area (stretching across East Vancouver and parts of Burnaby), a salmon run in such an urbanized environment is unique in North America. But the density poses challenges to the health of the fish. Pavement causes runoff and during heavy rainstorms road salt, oil and other toxic materials are washed into the storm drains, eventually ending up in the watershed.

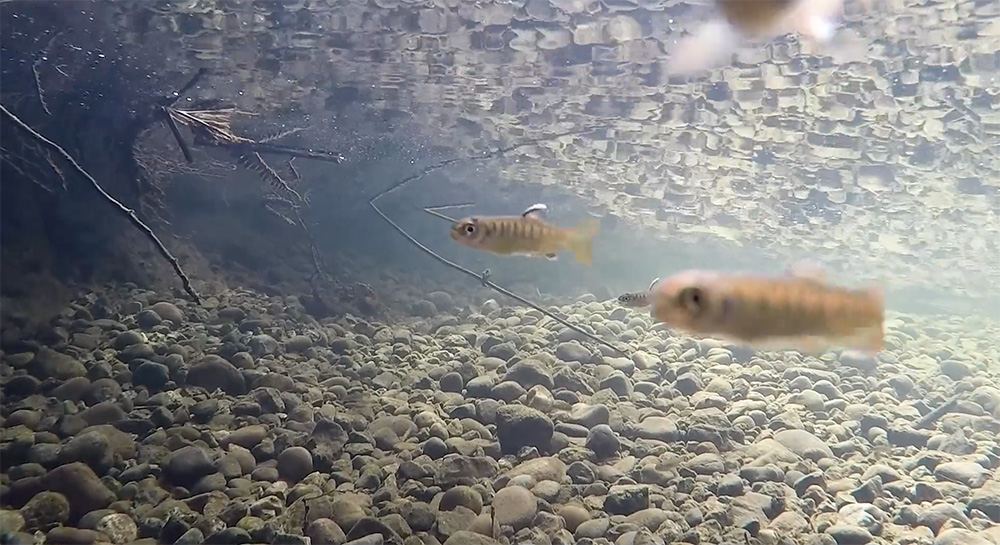

Young fish stay in their home streams for a year before they return to the ocean and are incredibly vulnerable to pollution. The film offers plenty of footage of curious smolts and fingerlings bumping into the camera lens like kids anywhere, bug-eyed and a bit goofy looking.

As much as there is to look at in The Return, there is also a great deal to listen to — crackling ice, distant birdcalls and the burbling onomatopoeia sounds of water, all set against the machine roar of the city. Dodis says her intent was to alert people to the nature right in their midst, winding between parking lots and highways. “There’s so much richness here,” she says.

But in order to get people to fight for nature, they first have to feel like it’s part of their home, their community. “That’s why I wanted to include a map on the website to show people where these streams are located."

Not unlike a salmon run, the making of a documentary film is complex. Grant writing, pre-interviews, actual interviews, filming, animation, editing, sound editing, and then the work of setting your creation free to swim on its own in the wild waters of film festivals.

One of the screenings that was most important to Dodis was a presentation at the Stoney Creek Environment Committee’s annual general meeting in Maple Ridge. Many of the members are aging, she says, and it’s important that the next generation picks up the work and carries on the work of the organization.

Where there is life there is hope, but different voices in the film make it clear that protecting salmon in the long haul requires a fundamental shift in values.

“When we share a landscape with other species, they become part of the community. It really helps us develop a sense of place and our identities become attached to the things around us, and we become the kind of people who will work harder to defend them,” writer MacKinnon says in the film.

But this kind of connection doesn’t happen in the abstract: it needs a place, a physical location and something that enables people to develop a sense of what MacKinnon calls “the big picture.”

MacKinnon says we need wild spaces, and without them people are “really missing opportunities to develop our humanity.”

Here’s where a place like Still Creek is critical. Beneath the lush growth, as salmon churn the waters, re-enacting an ancient rite, there’s a sense of older cycles of life taking place, a great web of interconnectedness where humans and fish can abide together.

'The Return' is part of the BC Voices Shorts Program and is available to screen as part of DOXA’s online virtual festival from June 18, 12:01 a.m. to June 26, 11:59 p.m. ![]()

Read more: Media, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: