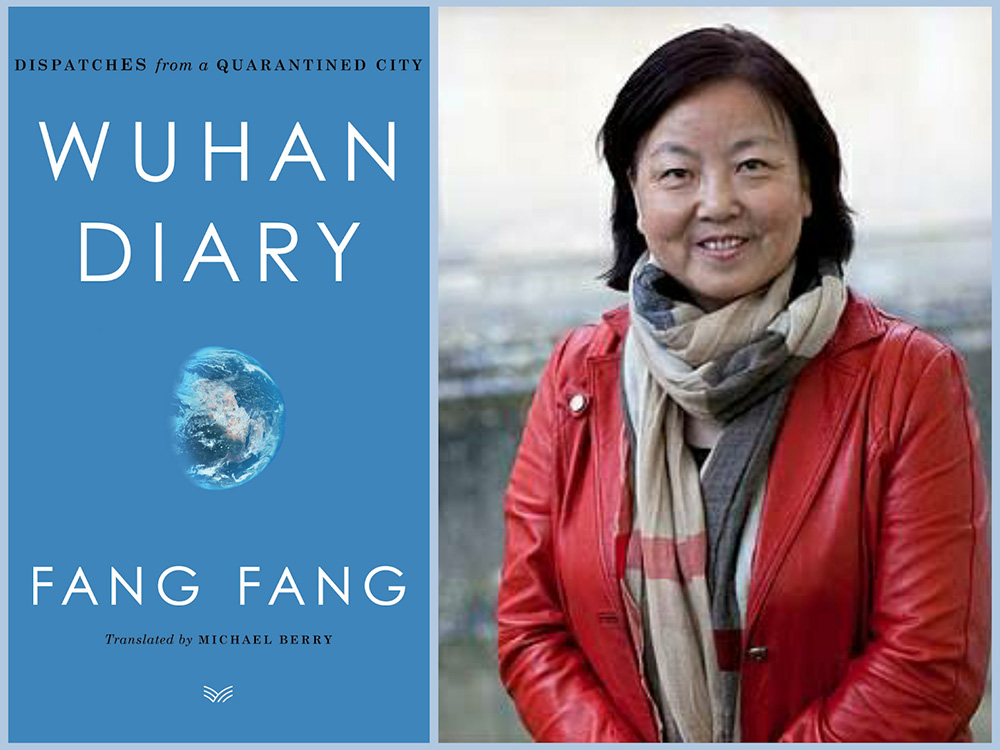

- Wuhan Diary: Dispatches from a Quarantined City

- HarperCollins (2020)

This book is an event as well as a document. It's the first book-length report on the emergence of COVID-19 in Wuhan, and its author is a notable Chinese novelist who is deeply unpopular with the government.

Wang Fang, who writes as Fang Fang, was born in 1955 and has lived through a tumultuous 65 years of Chinese history, from the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution to the age of Xi Jinping. Part of a well-educated family, she now lives alone (with a 16-year-old dog) in a Wuhan apartment complex reserved for writers and artists. Very familiar with online communication, she has been a frequent user of Weibo, the Chinese equivalent of Twitter, and WeChat, another social-media platform.

In Europe or North America, Fang Fang would be a well-followed member of what I call Flublogia — a loose network of people tracking outbreaks of infectious disease and swapping information on blogs and Twitter. Flublogia sometimes gets into quarrels with bots and trolls, usually over the issue of vaccines and now over the politics of COVID-19. But such spats are generally rare.

Fang Fang, by contrast, has been battling bots, trolls and her government for a long time. Before the outbreak, she'd often seen her posts taken down by government censors, and occasionally her account was suspended and then mysteriously restored. Some Weibo and WeChat users attacked her politics and patriotism, usually from a position she considered extreme left (Cultural Revolution) — and she wondered why their posts were never censored.

62 days in lockdown

Still, her posts and literary stature won her a large following, and it was natural for her to focus on her experience during the 62 days when Wuhan was completely locked down and she was effectively confined to her small apartment and an adjoining courtyard.

The result is a book that's plausible and sympathetic because her experience is so like our own. Admittedly it's more intense, because Wuhan was locked down first and hardest; we in B.C. have had a much easier time of it. But Fang Fang, like us, has to deal with boredom, lack of exercise, anxiety about daily case numbers, and the tedious logistics of shopping and cleaning.

Also like us, she spends a lot of time online — emailing, blogging and texting as well as talking with friends, colleagues and relatives. She gets much of her information from Chinese media, which of course have no independence from Beijing. She enhances this with an ancient Chinese method for coping with bureaucracy and official incompetence: guanxi, a network of personal connections to people who have news or the ability to get something done right away.

Consulting the networks

Fang Fang has very good guanxi. She has relatives and in-laws who are highly-placed academics and professionals, neighbours and colleagues consulting their own networks, and classmates all over China who keep in touch with one another by email and social media.

So she heard from one of her brothers about the mysterious pneumonia cases at Wuhan Central Hospital shortly before the official word came down on Dec. 31, and she often cites colleagues or friends or in-laws as sources of information. Some allowed her to use their names, while others preferred anonymity. As a result, her long daily posts were a mix of daily concerns plus informed overviews of an ongoing disaster — put together by a skilled writer in her little apartment.

Fang Fang seems like the kind of neighbour you'd love to have: good-hearted, smart, informed, full of gossip and very opinionated. It's no wonder, then, that her posts attracted a lot of followers, or that they were frequently removed from Weibo and WeChat. Or that they attracted incessant attacks from trolls, bots and fellow-Chinese who didn't agree with her. Fang Fang was critiquing the response to COVID-19 right from the heart of the disaster.

Beijing critiqued right back, with a series of attacks on her in the English-language Global Times that intensified when her diary appeared in English.

From Beijing's point of view, this book must look like a set-up job: her posts, including those deleted from the Chinese web, were transferred to the West, rapidly translated, and rushed into print with early fanfare from media like the Guardian. Fang Fang herself turned up tentatively on Twitter in April, then vanished. (Another account, Fangfang_wuhandiary, appears to be phony; it's in Chinese which Google translates into near-gibberish.)

So the postings of an elderly Chinese academic and writer have caused an international uproar, worthy of continuing response from the second most powerful government on the planet. It's as if Margaret Atwood or William Gibson had criticized the Canadian response to COVID-19 and brought down the wrath of Ottawa on their heads. If anything, such criticism here would only advance such writers' careers.

Why authoritarians fear writers

But character assassination is the homage that authoritarian governments pay to writers. Russia's tsars feared Leo Tolstoy as a kind of co-tsar, and the Soviets dreaded Alexander Solzhenitsyn for the same reason: people inside and outside the country read such writers with respect. Fang Fang has won the Lu Xun Prize, named for a radical pre-revolutionary Chinese author; Lu Xun, if he were writing in 2020, would terrify Xi Jinping himself.

I got a glimpse, when I taught in China in 1983, of some intellectuals who had survived the Cultural Revolution and were preparing their children and students for Deng Xiaoping's second Chinese revolution. They struck me as highly intelligent, better educated and more bitterly experienced than any western academic, and able to survive in China's whitewater politics.

Xi Jinping must know them far better than I, and he doubtless remembers Mao once called them “the stinking ninth” of China's population, the smart guys who think they know better than the Party. And of course, they do know better than the hacks and time-servers who run China from the towns to the provinces to Beijing itself.

Fang Fang knows better than to criticize Xi and his government; she attacks the local officials who did nothing until they heard from Beijing — an indirect attack on Beijing. She repeatedly reminds her readers of the critical 20 days in January when nothing really happened (“no human-to-human transmission!”) and the virus spread across Wuhan, then China, and then the world. Those responsible, she insists, should face justice.

Of course she's right. But by the same token, Donald Trump and his administration, and many other governments, should face justice too. At least Beijing has battled COVID-19 to a standstill, with about 84,000 cases in late May. Even Canada now has more cases than that, and the U.S. has a staggering 1.7 million cases and over 100,000 deaths. No one expects any immediate independent inquiries into the failures of our own response to the pandemic.

Apart from its political aspects, Wuhan Diary has strengths and weaknesses. Michael Berry's translation, while generally readable, was done under pressure (he was working 10 hours a day on it, he tells us in an afterword, while under quarantine himself in Los Angeles). It needs a polish, and the book itself would have benefited from tighter editing; Fang Fang can be as repetitious and long-winded as any other blogger.

But she also gives us a portrait of a China utterly transformed from the one she grew up in. She swaps texts with her translator; I can recall when a long-distance phone call from Guangzhou to Vancouver took a formal request and hours of waiting in a hotel lobby. She lives just four hours by bullet train from most major Chinese cities. She has her own car; a daughter lives in Singapore, and nieces and nephews are all over the world. China has come a long way since the Great Leap Forward.

Some old values persist. Fang Fang follows government orders to the letter. She praises the health-care workers who pour into Wuhan from all over China, and the spontaneous co-ops that form to organize food deliveries to locked-down residents like her. The trolls who attack her are “ultra-leftists,” a threat to everything China has achieved under Deng Xiaoping's policies.

No doubt many other books will emerge from this pandemic; I hope Dr. Anthony Fauci writes his memoirs, as well as workers in the intensive care units of New York and Montreal hospitals. Dr. Bonnie Henry's perspective will also be invaluable.

But whatever happens to Fang Fang, her Wuhan Diary will surely be a key document in the history of this century's first pandemic. ![]()

Read more: Politics, Coronavirus

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: