At the end of every driving lesson, my instructor Vincent takes his hands off the second steering wheel in front of him, gives me a high five and says, “You did it, girl!” He’s probably not much older than I am but is possessed of a gentle, even courtly manner. Even on the days when things don’t go well, he maintains an admirable equanimity. “It’s a process,” he shrugs. Which is perhaps a kinder way of saying, “You really sucked today, but maybe you’ll be better next time.”

The confines of a car create a strange, automatic intimacy. Before long Vincent and I exchange bits and pieces about our lives. I tell him about my son Louis getting ready to graduate and head off to university, and he tells me about his sister coming to visit. Some days we don’t say very much at all, but it feels comradely and comforting to have the presence of another body beside me with a second set of controls should things go wildly out of hand.

One day we drive all the way to Burnaby to where the road tests take place. We pull into the ICBC parking lot and get stuck behind a student driver who is trying to back into a parking space. It isn’t going too well — a series of attempts, lots of backing up and starting over again. I stretch my neck to see a young woman in the other car. Her face is a smeary pale oval against the window, her expression one of total despair. It doesn’t look like she has a hope in hell of passing her road test. “That will be me in six months,” I think.

Still, every couple of weeks, I show up at the driving school and enact the same routine — humiliation, inadequacy, moments of mortal terror and occasionally a brief snatch of joy. Some days it rains so hard I can barely see more than a few feet in front of me. Other days we simply sit in traffic, inching our way across the city. Secretly I am very happy when this happens. If you are only going five kilometres per hour, the chances of exploding into a fireball are actually quite low.

Driving at a normal speed is much more frightening. “You have to get up to the speed limit,” says Vincent. At 50 km/h, I feel like control could simply vanish at any second. It’s like a strange form of vertigo, a compulsion to go right over the edge and steer into oncoming traffic. Decades after crashing my mother’s car as a teenager, the panic and shame, the police officer saying “Don’t let this one drive,” are still there beneath the surface. In fact, every time I finish a driving lesson it’s as if I have cheated death.

The exhilaration lifts me across the parking lot, down Commercial Drive and onto the SkyTrain. Everything seems wondrous and remarkable — the taste of coffee, the smell of rain, the guy asking for change outside the dollar store — every corner of this dirty old city, aglow and pulsing with life. The feeling doesn’t last, and the next lesson I’m filled with the same dread and foreboding.

But slowly this driving business is getting easier. Things make a bit more sense and the car has started to feel less like a bulky metal body and more like a natural extension of my arms and legs. With this comes a new feeling of power and an imperious desire to drive over things.

I exaggerate, but only slightly. I’ve been left out of the larger cultural conversation for so long that I’m eager to make up for lost time. As a film critic and curator, I have tried to comprehend the appeal of works like The Cannonball Run, Smokey and the Bandit, Convoy, The Fast and the Furious and Transformers — all those movies and television shows and music videos that have featured humans inside cars, underneath them, and occasionally writhing around on their hoods. Until now, I never grasped such fetishized feelings for automobiles. But now I’d even exult in watching, if it existed, The Fast and the Furriest, wherein Vin Diesel and the gang penetrate a ring of International drug-smuggling plushies. Stomp on that gas pedal! “Look at me taking control of this mighty beast and pointing it where I want to go!”

You are your car. (If you choose to be.)

If this were a Hollywood movie, driving lessons would be a training montage set to “Eye of The Tiger” or maybe “Highway to Hell.” I would get punched down, then come roaring back up, battling to victory or at least to be a contender. Bloody, bruised but not beaten, I would drive off into the sunset. But reality is terribly unexciting compared to the movies. There’s just the work of trying to do things the right way and not fuck up too badly.

During my first few driving lessons, Vincent suggests we nose about the side streets of East Vancouver, edging around curbs and rolling over speed bumps in slow motion, stopping and starting, signalling and turning. The process is like learning a new language. You make plenty of grammatical errors and mispronunciations. But it’s all about communicating to the people around you about what you intend to do. If you fail to signal or stop suddenly in the middle of the street, other drivers let you know that you’re being unclear.

When I make a mistake in heavy traffic, panic freezes my brain and I make more mistakes. I forget to signal. I hit the curb. I go too slow, and people yell. I go too fast, and I scream inside my own head “WE’RE ALL GONNA DIE!” I have no sense of how wide the car is and swerve too close to parked cars. I forget basic things like looking in my mirrors or doing shoulder checks. There is a lot of detail, much of which you only realize a fraction too late when some guy zooms by and gives you the finger.

A few lessons in we practice left-hand turns, inching out into traffic, waiting for the yellow light, then swooping across the oncoming line of cars. However many times we do this it doesn’t get much less frightening. Some days I am filled with determination to conquer this thing. Drive, dammit! Other days I cancel lessons and hide at home like I’m avoiding the truant officer.

On the May long weekend, Louis leaves for Montreal to scout out universities. His father and I take him to the airport, put him on a plane and then proceed to fall apart. It’s only three days, but it’s a precursor of the big change to come. That afternoon I can’t function very well, so Vincent and I spend the entire lesson creeping slowly through side streets again, watching kids on their way home from school. I knew the day was coming when my own kid would say so long sucker and head off on his adventure. Still, it feels like a prelude to other endings.

On a sunny October afternoon, my twin sister Avril and I decide she will help me practice driving in Delta. It’s Sunday and with the exception of a few giant tractors and some random bird watchers, there’s little traffic on the skinny road on Westham Island. At the Reifel Bird Sanctuary, we park, get out and trade places. She, the lifelong driver, hops in the passenger seat and I settle in behind the wheel. To have switched positions feels weird and also interesting. Mostly it feels new.

We drive past pumpkins patches like pop art paintings, orange blobs of colour and squiggly lines carved into the raw brown dirt. We drive past seed farms, horse barns and grand houses fit for cattle baron ranches. Then it’s back over the one-lane wooden bridge towards the mainland. It’s a little like going back in time. Actually, it’s a lot like going back in time. The landscape reminds me of the Kootenays, the place where my driving career started and then ended in catastrophe. My sister and I talk about the things we always talk about and make the same stupid jokes.

Sometimes my earliest memories swerve into view — events that seem almost too weird to have really taken place. When this happens I usually ask Avril, “Do you remember this?” To which she replies, “Yep.” Being a twin gives you access to two perspectives separated by a just few degrees. It’s like seeing from two different sets of eyes simultaneously.

On June 15, 1971, Avril and I celebrated our fourth birthdays in Jasper National Park. (It is my mother’s birthday too. We were born the day she turned 19.) I remember the campsite we’d set up for the night, the picnic table and the store-bought cake with white icing and four fat red roses, one on each corner. I can see the way the trees grew together, thick and close, catching gloom between them.

I don’t remember when the grizzly bear decided to crash our party, just my mother bundling me into the Volkswagen bus. The grizzly was so large it had to bend down to look in the window of the van. My sister and I, high on cake and birthday surprise, waved at the bear. My mother was less than thrilled by the prospect of us all being devoured. The only creature with any sense turned out to be our cross-eyed Siamese cat Sapphire who stood down the bear, hissing and spitting, until we grabbed her and roared off down the road. Later that same night, after we’d pitched a tent and gone to bed, we were awakened once more by the sound of animals. This time it was a herd of horses. My mother caught one and gave Avril and me a ride.

In the Kootenays people have a habit of naming their cars. Like family dogs they all have distinctive personalities. I can see the long line of family cars, beginning with the Volkswagen bus that withstood a grizzly. After that there was a rusted-out Chevy sedan covered with patches of scabrous grey Bondo, with a gaping hole in the floorboard that we spat cherry pits through. When you looked down you could see the road rushing beneath your feet, blurred streaks of asphalt.

My mother’s ancient white pickup was called Dirty Gertie, because she was always coated with a thick layer of crud — the truck, not my mother, although they were both a bit begrimed. Later, when our second stepdad Len arrived on the scene, he drove a red Cortina that we called Fred, because Fred rhymed with red. When Red Fred finally kicked the bucket it immediately became Dead Red Fred.

Perhaps cars invite names because we live large chunks of our lives inside of them. Seminal moments take place there: make-out sessions, long meandering conversations with friends and family, summer road trips and winter journeys home. And if you aren’t paying attention to the signals, a grizzly bear wanting to eat your cake and maybe you, too. If you’re lucky, your mother will be there to save you.

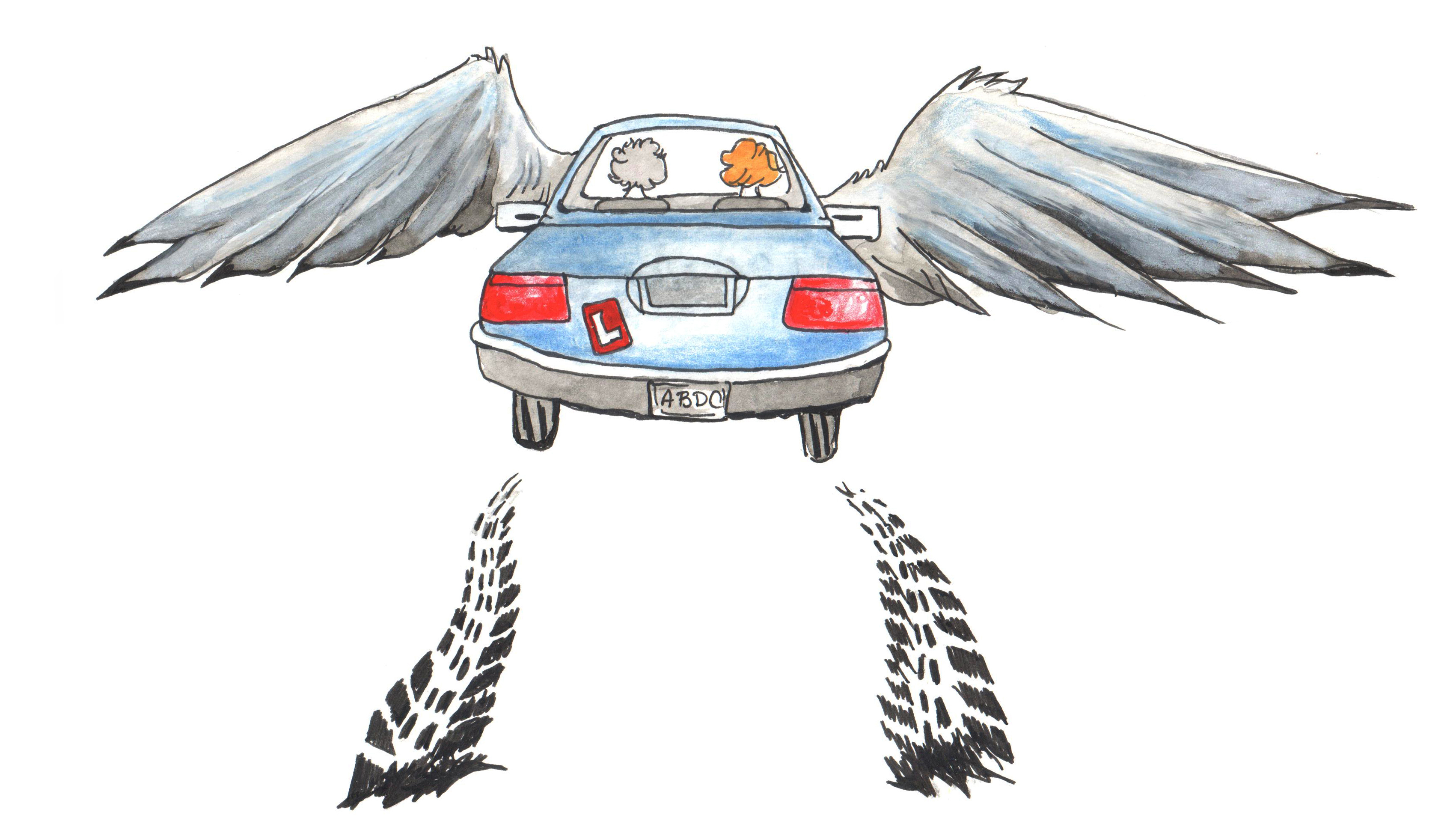

My mind snaps back to the highway before me. My foot gently nudges the gas pedal, then instinctively taps the brake to prepare for a mild bend ahead. Out of the corner of my eye, my sister seems pretty okay there in the passenger seat as I steer the two of us through a sunny afternoon in Delta. At first I don’t notice, but then I realize something. I forgot to be afraid. I have a sensation of flying that feels safe and free.

This concludes the four-part series. Find all the pieces here. ![]()

Read more: Transportation

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: