- At the Bridge: James Teit and an Anthropology of Belonging

- UBC Press (2019)

Cultures are stubborn and almost immortal. Many European and Latin American apartment buildings are built like those of Rome, and bullfights are akin in spirit and purpose to gladiatorial combat.

Similarly, Indigenous cultures in Canada have stubbornly survived despite over a century and a half of calculated oppression by white Canadians and their governments. And Canadian governmental culture since Confederation has been equally stubborn in its determination to destroy the peoples it has expropriated.

Wendy Wickwire makes that clear in this epic account of James Teit, who not only preserved much of B.C.’s Indigenous culture in the 19th and early 20th century, but fought Ottawa’s malevolent racism every step of the way.

Teit was born in 1864 in the Shetland Islands, a Scandinavian community long ruled by the Scots and then by the English. It had been one of Britain’s first colonies, with its own dialect and culture, and by the late 19th century it offered little to its own people. As a young man Teit was glad to have an offer from his uncle to work for him in Spences Bridge, in distant British Columbia; the rest of the family scattered around the world. Like their former masters the Scots, Shetlanders had become a diaspora, a world people trying to make a living where they could.

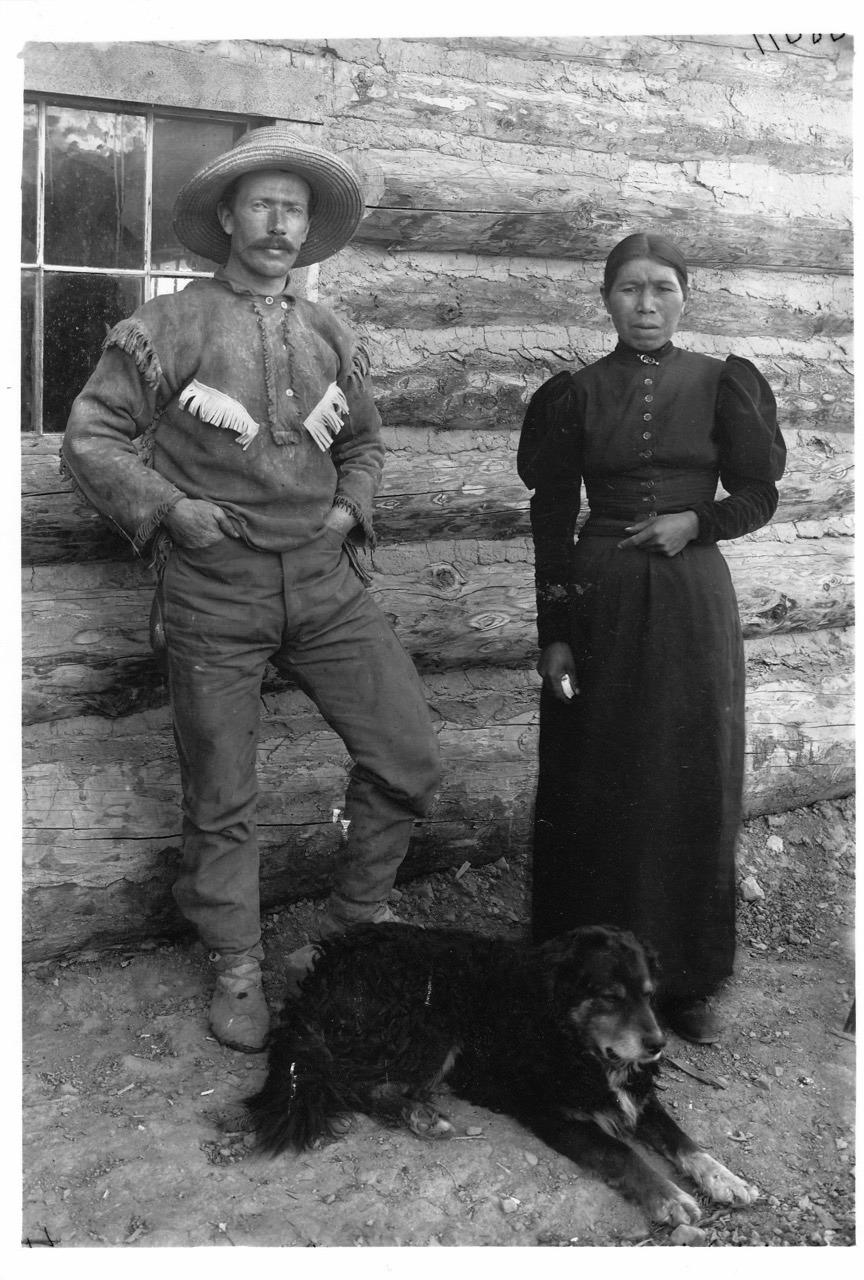

Arriving in 1884, Teit adjusted quickly and learned far more about his new home than most settlers ever did. He met and liked the Indigenous Nlaka’pamux, known to most whites as “Thompson River Indians.” He listened to them, learned their language (and other Indigenous languages), hunted with them, and married one of them, a young woman named Antko.

In the eyes of most British-born settlers, this was a serious lapse in judgment. Teit was a “squaw man,” what modern white nationalists would call a “traitor to his race,” but he had no special affinity for the Brits who considered Shetlanders just another colonized people. In a decade, his Indigenous wife and other mentors made him the strongest link between them and their European rulers.

Reeling from the onset of empire

This was at a time when Indigenous societies across Canada were reeling from the onset of empire. Repeated epidemics of smallpox and measles had reduced their population and broken their cultures. Gold prospectors had marched up from the U.S., triggering a series of wars in the B.C. Interior. Indigenous peoples were crowded off their land and their children were crowded into residential schools. The young dominion of Canada was determined to solve the “Indian problem,” whether by assimilation or extermination.

A young German anthropologist appeared in Spences Bridge in 1894. Franz Boas was a brilliant man, determined to turn his discipline into a science. But he approached B.C.’s Indigenous peoples like a time traveller interviewing residents of Pompeii just before Vesuvius erupted. Boas considered them as barely living archaeological specimens, who could provide details about their languages and culture before they vanished altogether.

Predictably, he’d gone nowhere until he met James Teit. Teit had already become a kind of self-educated ethnographer, and he was happy to do well-paid research for Boas. But he regarded the people he studied as members of a living, developing culture, who were happy to share their knowledge with someone they trusted. After all, Teit spoke their language.

Boas seems never to have understood why Teit’s material was so good. He stripped out the personal details and pestered Teit for irrelevant minutiae about the techniques of basket weaving. Still, both men benefited. Boas was drawing attention to Indigenous cultures at a time when settlers couldn’t have cared less, and Teit was able, with Boas’s funding, to explore many Indigenous B.C. cultures. By the end of the 19th century, Teit was probably the best-informed European in North America on the present state of its Indigenous peoples.

The man who listened

The peoples themselves recognized this. Few of them could even speak English, let alone understand what settlers were going on about. Teit actually listened to them, and understood. He could interpret settler culture and values in terms they understood. So Boas found his convenient research assistant was often working for Indigenous employers, gradually becoming their spokesperson in Ottawa.

As such Teit soon ran afoul of Duncan Campbell Scott, the Canadian poet who was also the civil servant in charge of “Indian affairs.” Scott believed that “only through the great forces of intermarriage and education will [we] finally overcome the lingering traces of native custom and tradition.” We fret today about whether genocide is a cause of the missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls; genocide was Scott’s whole policy. At one point Scott actually ran a crude espionage campaign to try to discredit Teit, who was being paid a nominal sum by Indigenous chiefs to speak (and interpret) for them.

While Teit continued in that role, he supplied Boas with still more information, lost his Indigenous wife to pneumonia, married a European, and eventually, in 1922, developed bowel cancer. Radiation treatment at St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver seemed to have saved him, but late that year, at 58, he died — of a pelvic abscess that he’d been too busy to seek medical help for.

No one could replace James Teit, but both the Canadian government and the anthropological establishment were eager to make him an unperson. Ottawa pursued its policy of assimilation for the next century, while reluctantly paying a little lip service to “reconciliation.” Incidents like the death of Colten Boushie show how far reconciliation can go.

Franz Boas and his disciples downgraded Teit’s work, which had helped make their careers and shape the whole science of anthropology, as merely the contribution of an “informant.” Much of Teit’s work remains unpublished.

But it survives. Wendy Wickwire, a professor emerita at the University of Victoria history department, has studied Teit’s life and work for decades, all the way to Shetland and across British Columbia. Her magnificent book is a massive revision of B.C. and Canadian history. It demands not a staged apology on the floor of the House of the Commons, but a genuine change of heart and policy throughout Canadian politics and government.

That will require a change of heart in all Canadians, many of whom have little interest in Indigenous peoples and less desire to treat them as equals.

We may mark some progress toward that change of heart if we remove some Ottawa statue of Sir John A. MacDonald and replace it with one of James Teit and his Nlaka’pamux wife Antko. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: