How can you tell it’s a Yucho Chow photograph?

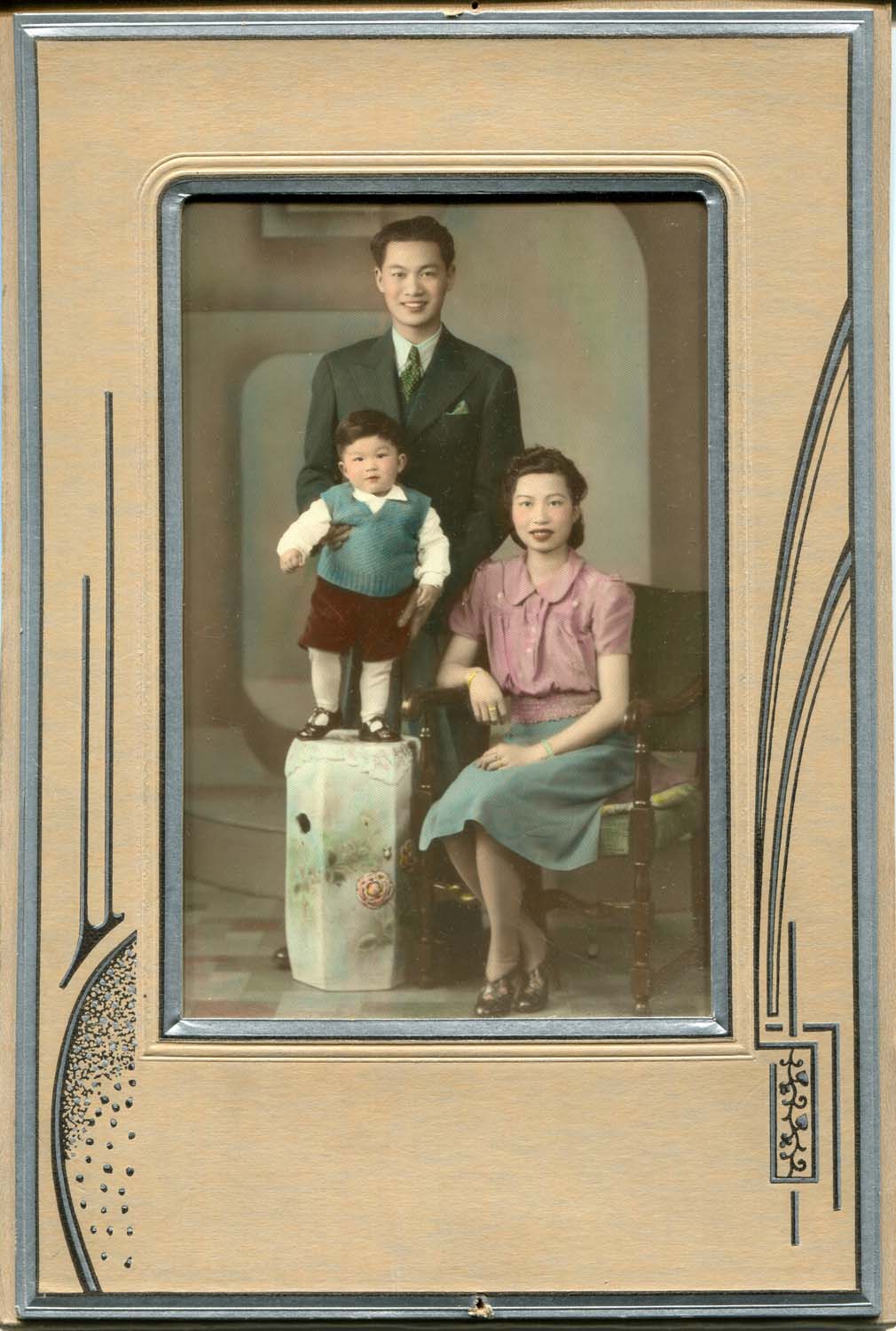

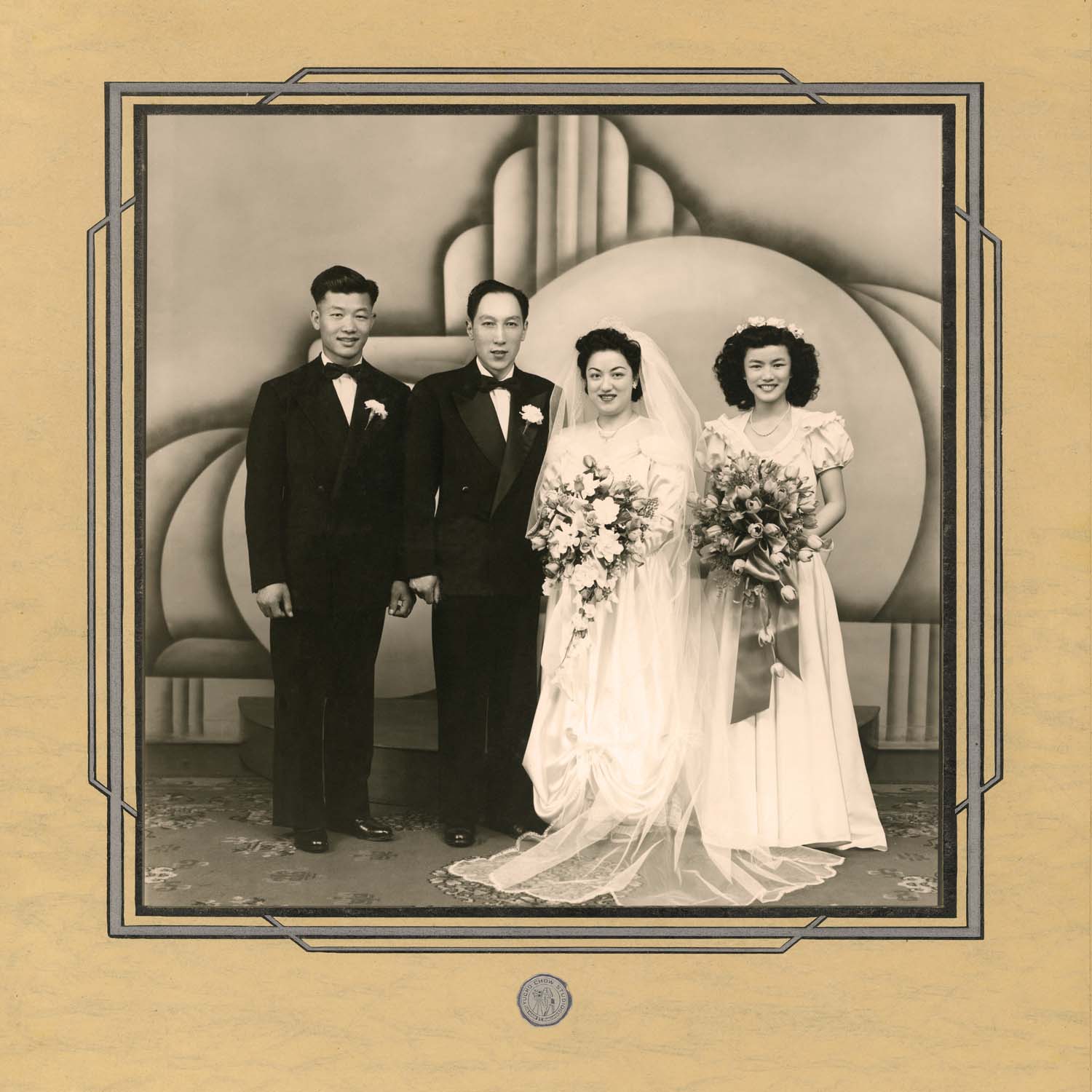

There’s the signature seal bearing Chow’s name, but if it’s missing, there are plenty of other clues: ornate props like gold pocket watches or faux marble pedestals, grand backdrops in art deco and French baroque styles and many Vancouver subjects who aren’t Anglo whites.

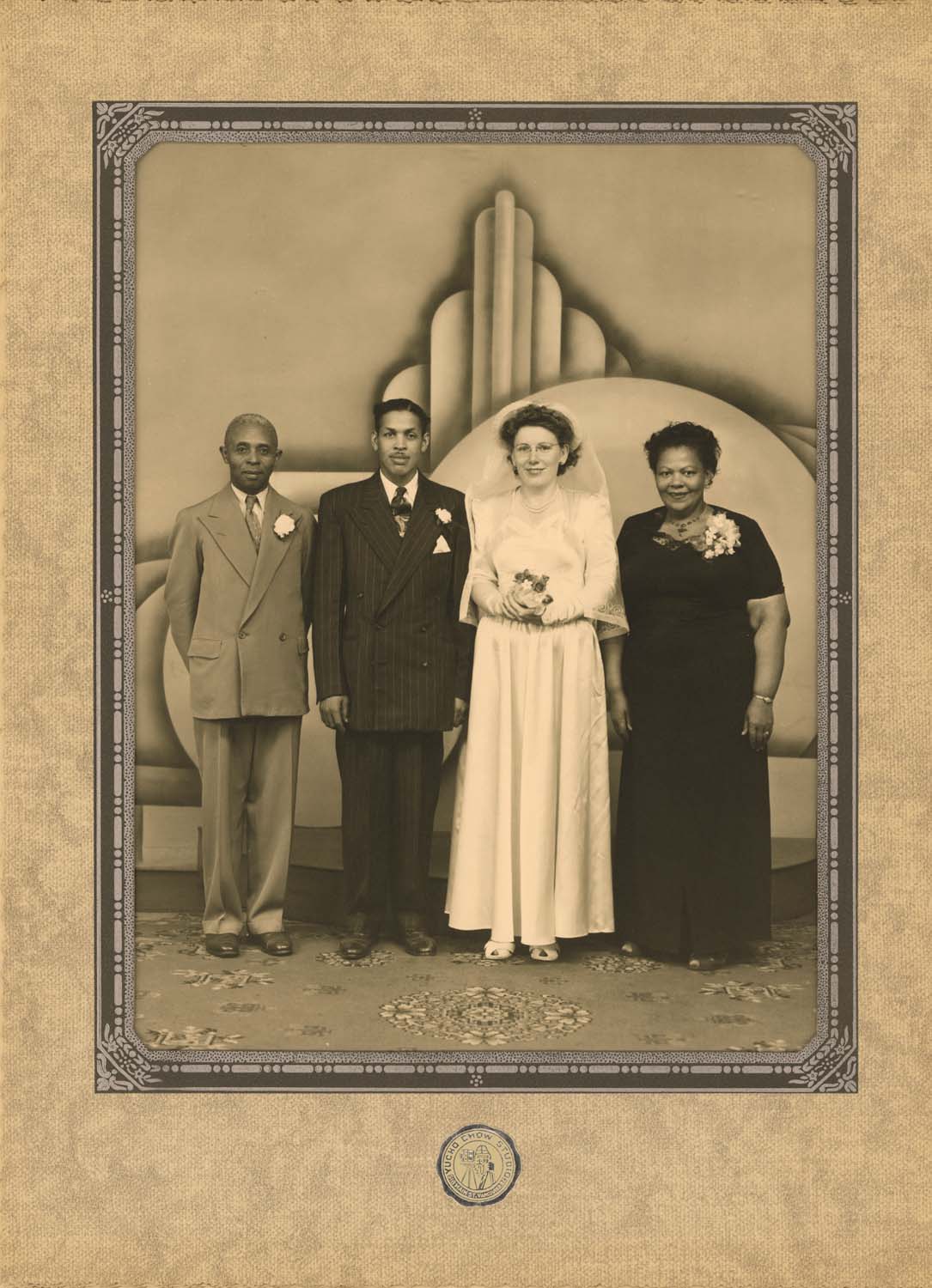

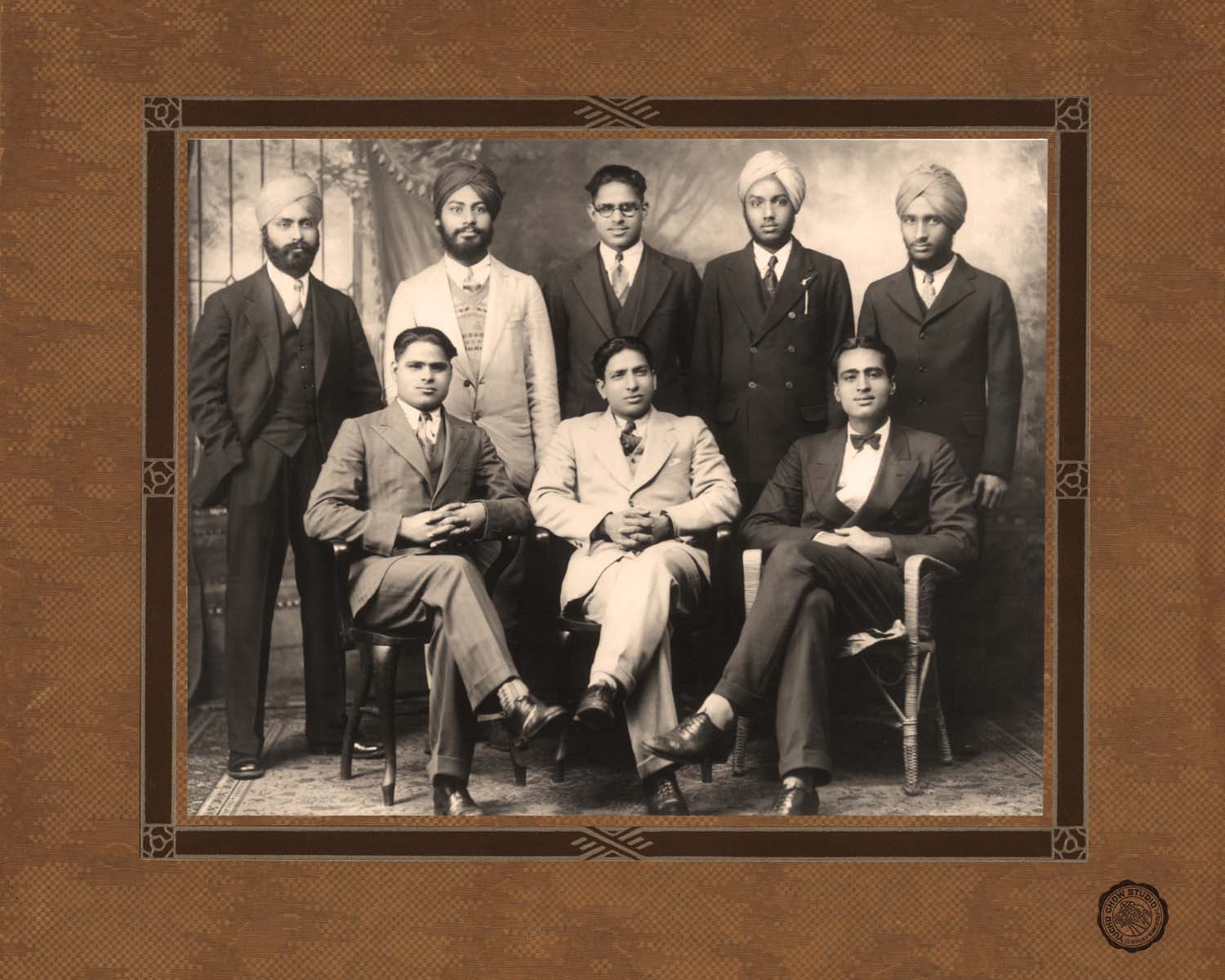

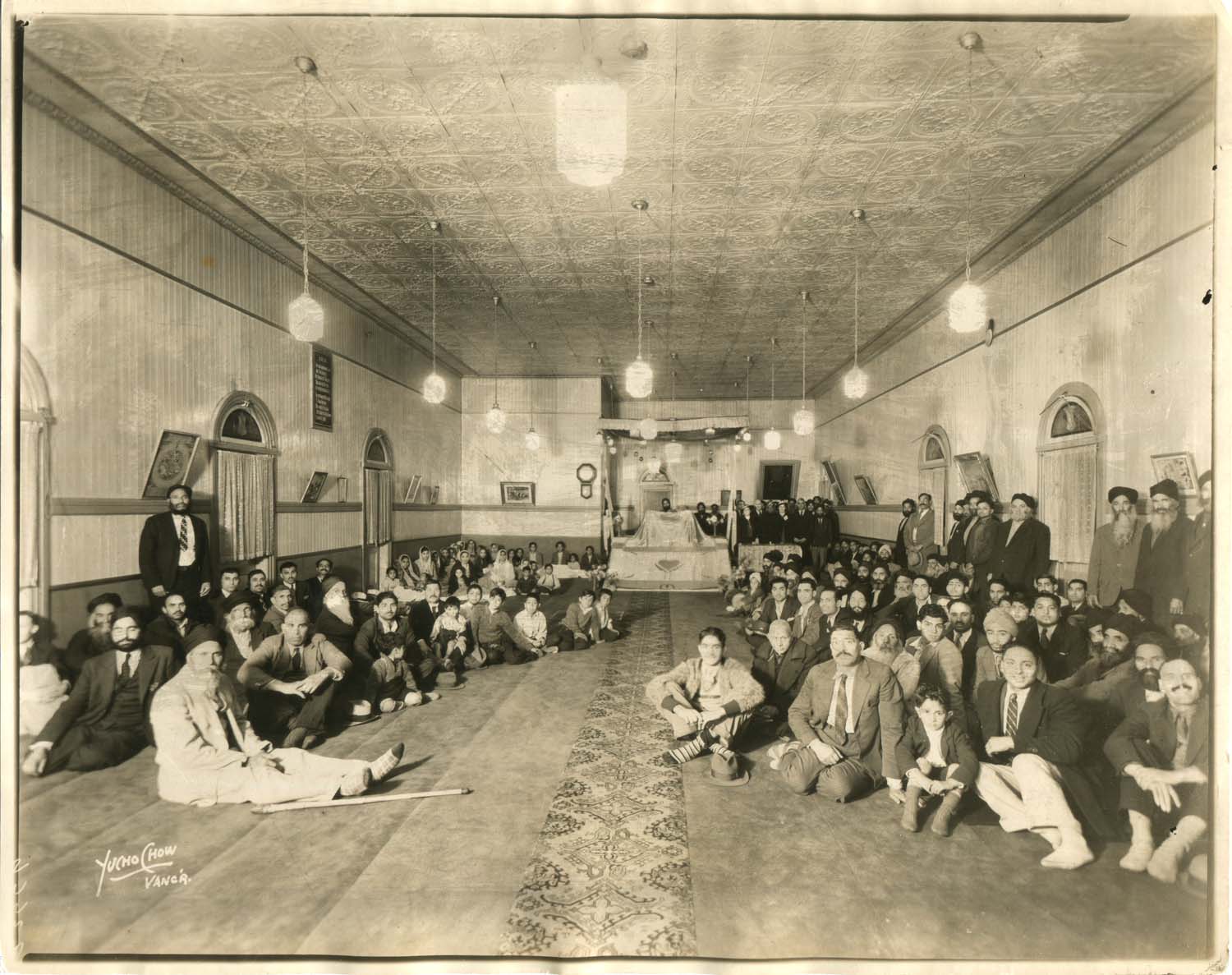

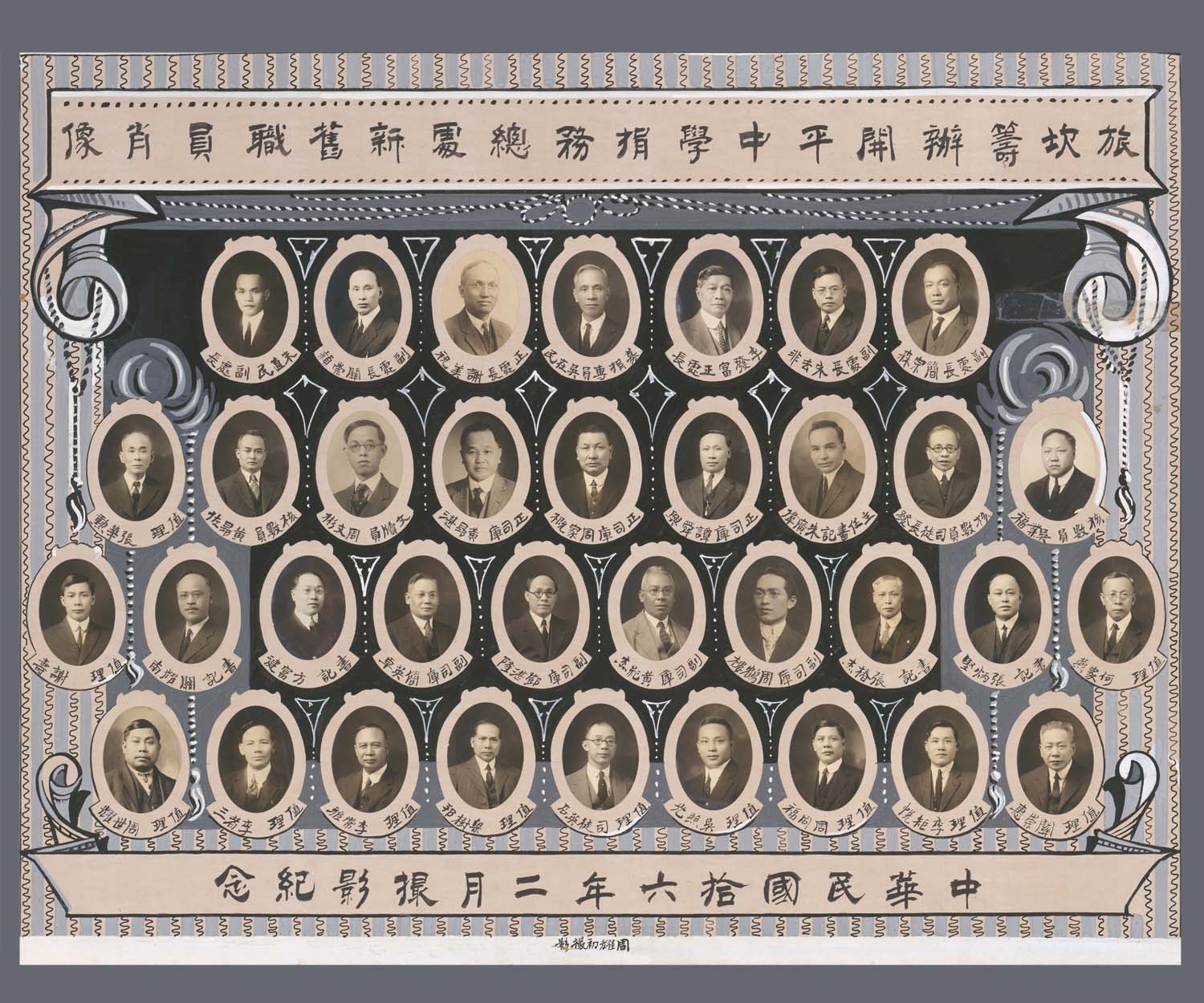

Throughout Chow’s career from 1906 to 1949, he often photographed the city’s minorities and marginalized, dressed in their finest. A look at the faces might surprise you.

They are members of the Vancouver’s early black, Chinese, Indian, Indigenous, Italian, Japanese, Polish and Ukrainian communities.

They are activists, athletes, entertainers and war veterans.

There are individual portraits, wedding photos of mixed-race marriages and shots of large immigrant families.

The fact that these photographs were taken is something of a miracle. Most white-owned businesses of the day, from photo studios to restaurants, only served white customers.

But Chow opened his studio door to anyone, and for marginalized people in an unfamiliar and unwelcome society it meant a lot to be able to commemorate an occasion with a photograph.

“They wound up in Chinatown, and Chow wound up being adopted by them,” said Catherine Clement, who’s been patiently tracking Chow’s legacy since 2010. “He became their chronicler.”

This makes Chow’s work much more than just pictures of family and friends for private albums; his photographs are a historical reminder of the diversity of people who, despite discrimination, made a life in the early decades of the city.

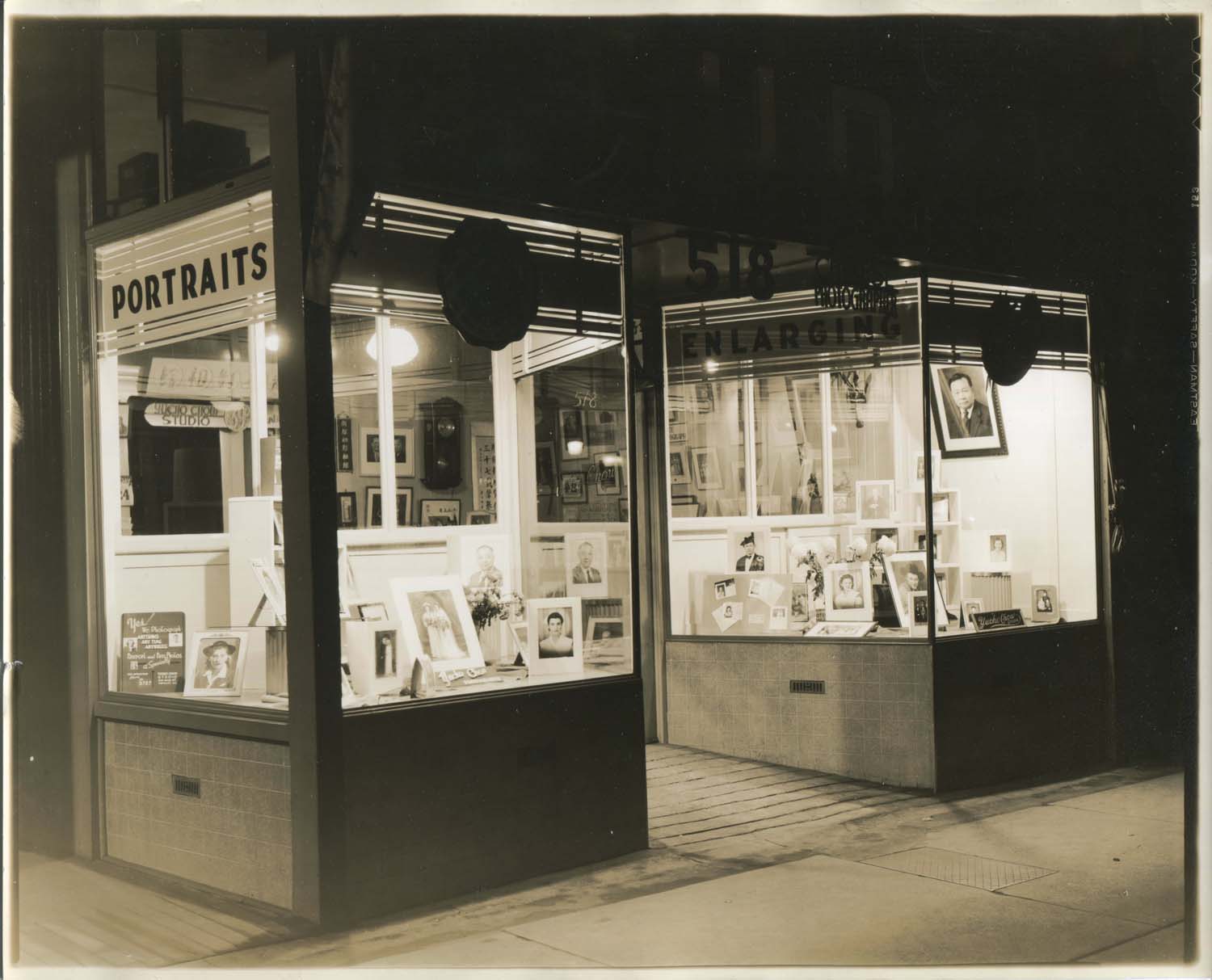

Chow’s legacy was never publicly recognized before Clement’s detective work. This month in Vancouver, thanks to her persistence, Chow’s photographs are exhibited for the first time.

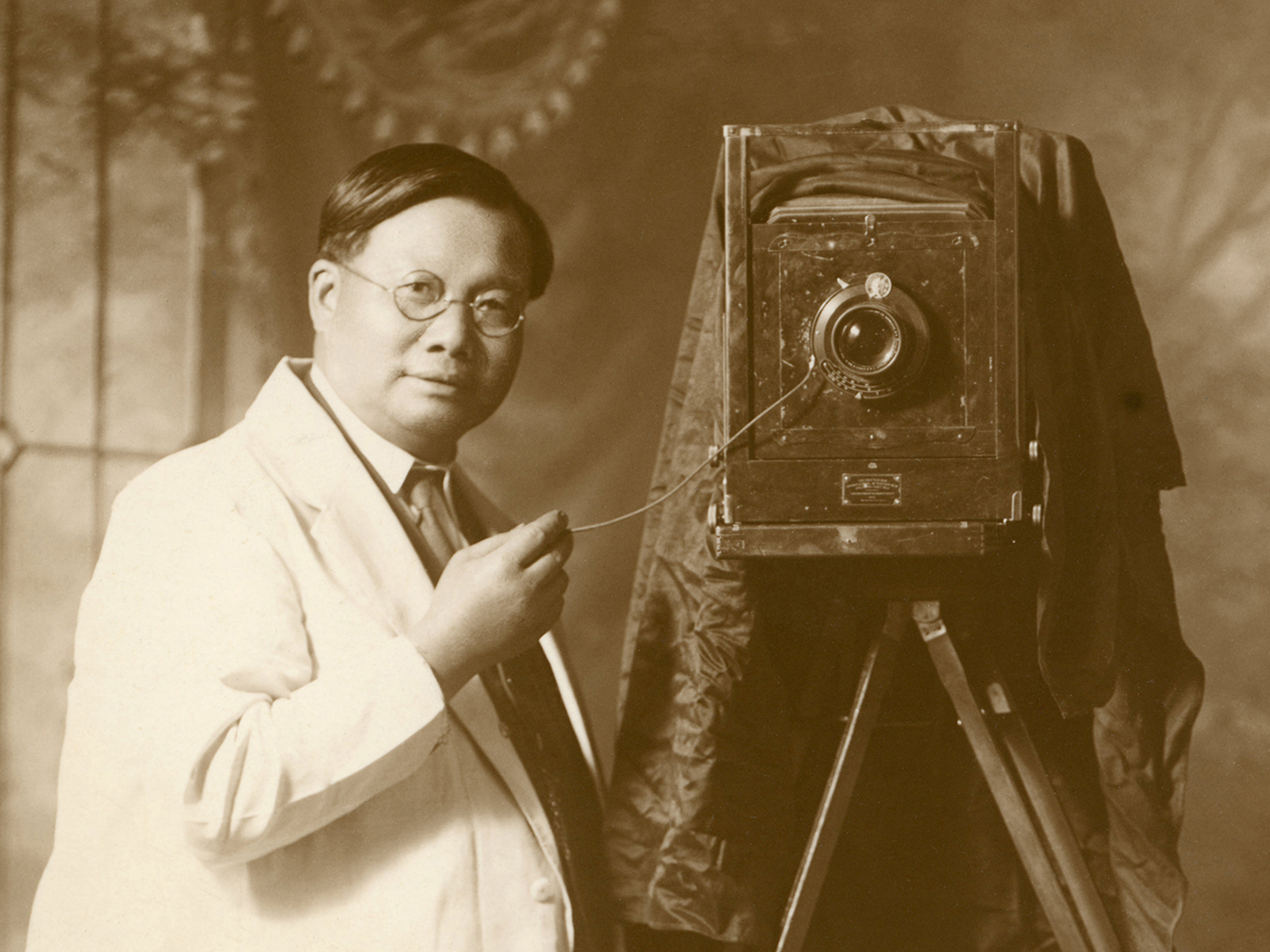

The search for Yucho Chow

For Clement, it all started during her work as the curator of the Chinese Canadian Military Museum interviewing veterans and their families. She noticed that many of their photographs bore a similar seal with the name of Yucho Chow.

“Every time I went to another person’s house, I’d see the seal,” she said. One creative variation of the seal had Chow’s name in Chinese in the shape of a photographer and his camera.

“Also, the name is really catchy! I thought I should just look up this guy, and that’s when I found there was very, very little on him — just a smattering of pictures here and there.”

So Clement began collecting. If she came across a Chow, she’d ask the owners to tell her something about the photograph and for permission to scan it.

“I got really obsessed,” she said. “Every time I found one it would be joy — and then the next day I’d be looking for the next hit.”

At first, progress was slow. Photographs she suspected were Chow’s were often marked unattributed or photographer unknown.

But Clement began to recognize enough signs of Chow’s work to identify which photographs might have been his. Chow showed a sense of artistry with his taste in backdrops and furniture. Much of that flair, which included books and jewelry, was to make subjects appear affluent.

His work was “everywhere and nowhere,” she said. The fact that the photographs were widespread yet elusive fuelled Clement’s search all the more.

“Given his body of work through the 1907 race riots, escalating head taxes, the First World War, the Chinese Exclusion Act, the Great Depression, the Second World War and the winning of citizenship [for Chinese Canadians]… that’s a really transformative and tumultuous period of time,” she said. “I felt an obligation to try and help people remember his story.”

In 2015, Clement finally came face to face with Chow. She found her first photograph of the man himself as part of her work with the museum thanks to Chow’s granddaughter, the widow of a war veteran.

When it was unveiled as part of a city-sponsored Chinatown exhibit two years later, her quest picked up speed as people called in with their pieces of the puzzle.

“Suddenly I was meeting Polish families and Ukrainian families and black Canadian families,” said Clement. “I had been pulling on this thread that was a really big tapestry.”

Chow wasn’t just a photographer of Chinese Canadians, they told her; he was the photographer of other marginalized communities too. It didn’t matter if they lived far from his Chinatown studio.

It meant a lot to have someone like Chow who welcomed them at a time when “they couldn’t get a white tailor to make them a suit or a white barber to cut their hair,” Clement recalled. People who appeared white, like Ukrainians, but were not Anglo, experienced discrimination too.

Clement found pictures everywhere from Abbotsford to Barkerville, treasured by families and in private collections and universities.

Clement learned more about Chow’s life, though there is still plenty of mystery.

Chow was born in what was then called Hoy Ping in southern China in 1876. It is believed that he came to Canada around 1902; immigration officers at the time did a poor job documenting names.

Chow was a houseboy in Canada before he opened his first studio in 1906, but it’s not known where he learned photography. “Somehow, he managed to find time during his schedule to apprentice with somebody,” said Clement.

Chow made trips to the train station to photograph European immigrants from eastern Canada getting off in Vancouver, but it’s not known whether someone commissioned him to do this or if it was a personal project.

Chow also didn’t work alone: the studio was a family affair. His daughter Jessie was known for her work colouring photographs with paint.

When Chow died in 1949 of a heart attack, his sons Peter and Philip ran the studio until 1986, though they did away with their father’s signature trademarks like ornate seals and painted backdrops in favour of a simple curtain and linoleum floor.

Upon closing, all the negatives were destroyed.

Lost and found

The 80 photographs are featured in this month’s Yucho Chow exhibition curated by Clement are reproductions of selected prints she painstakingly tracked down over the years.

Some were found on eBay and at thrift shops like Value Village. Like the work of street photographers Vivian Maier or Vancouver’s own Fred Herzog, Chow’s work was also unveiled long after the photos were taken and challenge our perceptions of a place.

But even when Clement found a Chow photograph, it wasn’t guaranteed that a story would come with it.

“One of the sad things I’ve noticed over the years when I’ve done this work of recording people’s stories is how quickly knowledge is forgotten within three generations,” said Clement. “Most of who you were and what you’ve done is forgotten. It’s a really short window.”

But her quest to learn about Chow’s photographs encouraged many Vancouverites to connect with elderly relatives to hear about the people in the pictures.

The exhibition, called “Chinatown Through a Wide Lens,” is an intimate look at Vancouver’s past, plucked straight from family albums. Accompanying many of the photographs are rich anecdotes that humanize history, but the details in the images alone will have you wondering about the stories behind them.

What did it mean for Chinese university students to win a prestigious soccer trophy?

What were attitudes like towards marriages between Chinese and Musqueam or black and white people?

In a group photograph of a young Sikh Canadian association, is it a sign of westernization that some members are wearing turbans and others not?

The dates of the photographs are also telling.

There are a number of Japanese Canadian weddings from the 1960s, a document of their lives after the Second World War when the government had interned British Columbians of Japanese heritage.

One date tells a story about the Chows themselves: the wedding photo for a Walter and Mary Sierpina was taken on Nov. 12, 1949, two days after the death of Yucho Chow. It is proof of the family’s tremendous work ethic during a time of loss.

Some migrant stories have surprising endings. A young Indian man who makes it to Vancouver ends up homesick and returning to India. The McKay family of Richmond helps their Chinese houseboy return to China, only for the houseboy to feel out of place and return to Canada.

There is also evidence of the social nature of the postcard-sized prints that existed outside of family albums. Some customers would purchase multiple prints from Chow and pass them among family and friends. In the exhibit, the photograph of a suave looking Harry Lee is addressed to “Dearest Rose.”

The sharing of photographs with relatives overseas was especially important. Chinese residents sought out Chow for photographs of newborns, and the closed eyes of dead relatives, a kind of informal death certificate sent back to families in China.

Chow also offered post-processing services to bring families together, editing separate photographs of wives in China and husbands in Canada to unite them within a single image.

Though the price of a session wasn’t cheap. Some of the exhibited photographs were commissioned by friends or family who pooled their money together.

The vibrancy of the exhibit cannot be doubted — there are so many different celebrations and vaudeville acts documented — but there is also an air of melancholy as we read about death, discrimination and separation.

One particularly moving section of the exhibit documents three generations in the life of an immigrant Polish family. A man named Alexander Klimec is photographed alone by Chow, then again years later with his wife Juliana and two daughters after they are reunited.

In the next photograph, Alexander is missing — he died in a sawmill accident. But the family continues visiting Chow. Two supportive cousins appear in the next family photograph.

And in the final two images exhibited, the couple’s eldest daughter returns to Chow with her husband for a wedding photograph, and again years later for a photo with their daughter.

Despite the melancholy, the photographs tell stories of resilience. There’s a black entertainer who later fights for civil rights, Chinese who go to war for a country that doesn’t recognize them as citizens and a touching story about white Canadians who lobby for their friend Bill Lim to be accepted into the tony Capilano Golf and Country Club.

There’s something for everyone to recognize in this exhibit. There are the people behind old Vancouver businesses still around, such as Benny’s Market or the Ovaltine Café. Followers of politics might recognize a young Wally Oppal, a future attorney general of B.C. Military buffs might marvel at the photograph of humble veteran Harry Gong, the only Chinese Canadian to pilot a Spitfire.

The exhibit shines light on our history, but also reminds you there are many holes. Photographs with unidentified people have plaques that ask: do you know them?

It may be a pity that we don’t know more, but these holes make the exhibit feel more real. Isn’t the fear of forgetting part of why we want photographs at all?

“There’s a commonality present in our desire to remember and be remembered, to be dressed in the finest clothing, to celebrate special moments,” said Clement. “It reminds us we’re more alike than we’re different, not matter what our background is.”

But with this daylighted body of work, we will not forget the name of Yucho Chow.

The Yucho Chow exhibit “Chinatown Through a Wide Lens: The Hidden Photographs of Yucho Chow” is on display at the second floor of the Chinese Cultural Centre at 555 Columbia St. in Vancouver until May 30. It is open Tuesdays to Sundays between 11 a.m. and 5 p.m.

Do you suspect you may have a Yucho Chow? There’s a guide to identify his work here.

Catherine Clement is still looking for more of Chow’s work. You can bring your photographs to the exhibit to be scanned to the archive on May 25 and 26 or contact Clement at [email protected]. ![]()

Read more: Photo Essays

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: