- Chop Suey Nation

- Douglas & McIntyre (2019)

I’ve always known “chop suey” as bad words. Literally, assorted scraps. Leftovers. Odds and ends. An inauthentic culinary abomination whipped up by Cantonese sellouts and served to know-nothing North Americans.

Ann Hui’s Chop Suey Nation proves I’m the real know-nothing. I learned that dishes I thought were random fusions — items as innocuous as ginger beef — are actually thoughtful creations, crafted with trial and error by immigrant chefs for foreign palates.

While chop suey dishes deserve praise in their own right, they’re also part of a bigger legacy.

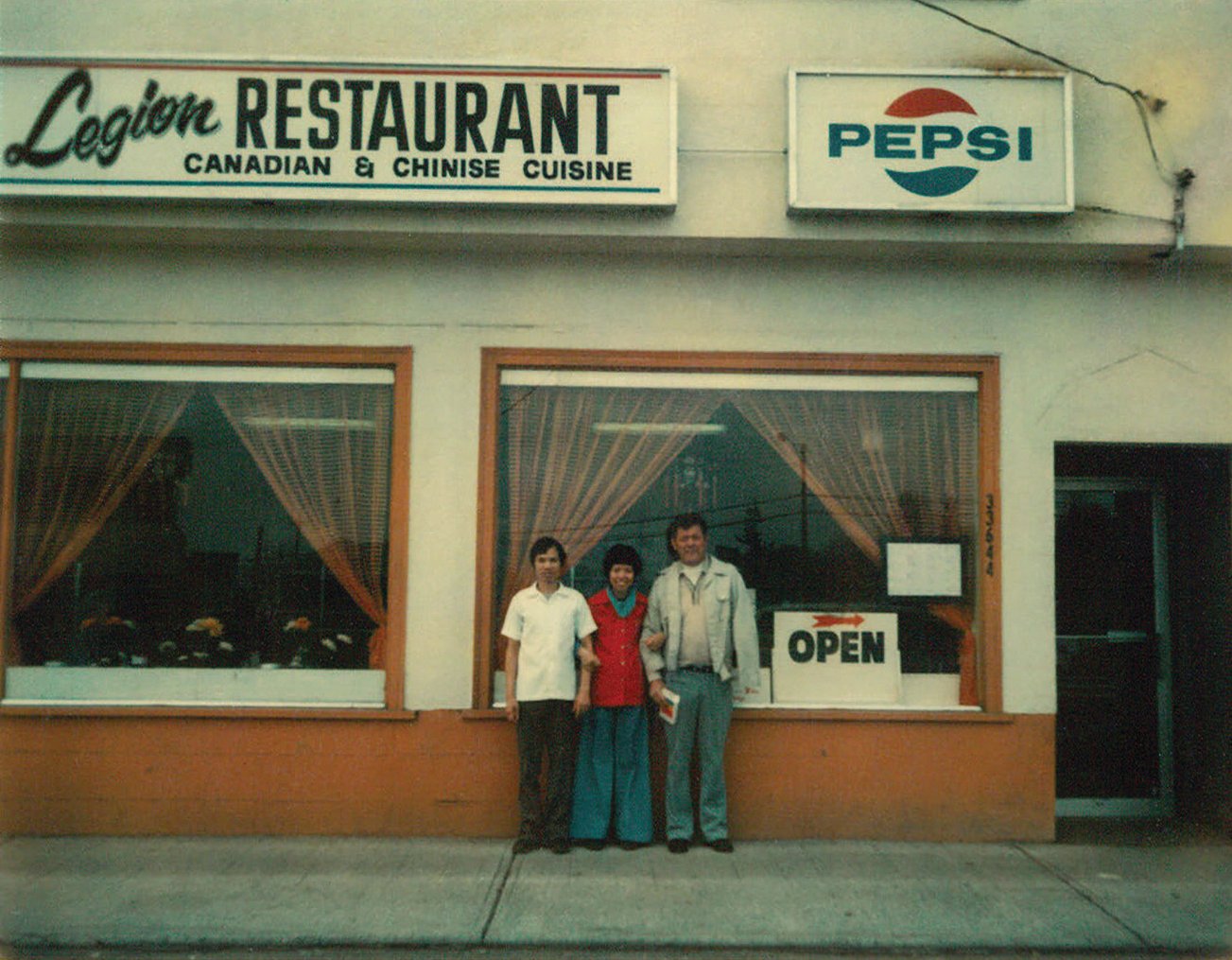

In her book Hui tells the rich history of the Chinese Canadian restaurants that chop-suey cuisine emerged from, and how these places gave, and are still giving, bright futures to generations of immigrant families.

The book itself is a thoughtful chop suey, with chapters leaping through three moving odysseys.

First, there’s a road trip from coast to coast, Hui’s quest to uncover why there are Chinese restaurants scattered across Canada, from prairie towns to inside a Thunder Bay curling rink to Fogo Island. (It was originally published as an essay in the Globe and Mail in 2016 to great acclaim.)

Then there’s Hui’s own story of growing up as the Chinese-Canadian child of immigrants, wrestling to understand family, culture and identity.

There’s also the life of Hui’s father and his journey from Cantonese China to Canada, from the bustling kitchens of Vancouver’s Chinatown to running a diner and buffet in Abbotsford with Hui’s mother.

It’s a seamless retelling — particularly scenes in Guangdong; summertime at the lake, hunting for clams — considering what must’ve been a laborious effort on Hui’s part to stitch together her father’s life shared through snippets over many conversations.

This was a tough book to research. Hui may be a reporter with the Globe and Mail but, as she mentions in the book, that could mean nothing to immigrant sources who often struggle communicating with English-speaking salespeople and bank tellers. Why would they talk about their lives with a stranger? As we meet restaurant owners for the first time with Hui, there is some shyness and suspicion — but they open up.

Readers are welcomed into the dining rooms of eateries both humble and lavish. Thanks to Hui’s skill at connection, you’ll feel like you’re sitting with her as she meets the owners face-to-face, hearing their voices and stories, sacrifices and joys.

A less delicate writer may have exotified these immigrants’ quirks and struggles into tales about weird restaurants in small towns with sad owners. Hui writes with empathy, presenting these people as they are, and tying them to a bigger Canadian story.

In the book we meet Mayor William Choy, who — on the side — runs Bing Restaurant No. 1 in Stony Plain, Alta.

There’s also Lan Huynh of Thai Woks N’go, who sells both “Chinese” and Ukranian pierogies in Glendon, Alta., home of the world’s largest pierogi.

And we meet Huang Feng Zhu of Kwang Tung Restaurant on Fogo Island, whose husband runs a Chinese restaurant in Twillingate, two hours away by car and ferry, so their family could have two incomes.

Some are longtime Cantonese immigrants, some came more recently from Mandarin-speaking China, and some are Canadian-born. We also meet Vietnamese, Korean and continental European immigrants with the similar experience of adjusting to a new home.

In the background, we see things like a bed on the side for tired restaurant kids to nap and a framed photo of a university graduation.

We hear of jobs left behind in China, ranging from air conditioner repair to working in the big city’s 100-cook kitchens. We hear of the dream pursued — simply for the children “to be OK.”

We learn of the informal economies that exist outside of formal social services, job offers and restaurants for sale communicated word of mouth by somebody’s relative or friend of a friend, powerful enough to trigger a move overseas.

And if someone needed a loan to get started they went to someone they knew, not the bank.

Authentic or fake?

We also unpack the two-menu phenomenon, common at North American Chinese restaurants: one traditional and one chop suey, with all the moo shu pork and egg foo young you could want. Is one “authentic” and the other “fake”?

I certainly held this mindset for most of my life, having grown up and lived in Metro Vancouver, an Asian immigrant gateway where you can order cheap mom-and-pop eats like salt-and-pepper chicken fried steak and cold, slippery liang pi noodles, as well as fancy fare like gold-painted dim sum and whole cod bubbling in a vat of hot peppers.

I remember being appalled at age 11 when my family ate at a chop suey restaurant called Ho Ho Yummy Food on Denman Street in Vancouver. The stuff screamed Chinese to me in a gaudy, embarrassing way.

But I was hit with a big one-two when I read about Kwong Cheung of Calgary and the ingenious story of how ginger beef was created in the 1970s by Cheung’s brother-in-law, George Wong.

Wong wanted guests to buy more alcohol at his restaurant, so he started brainstorming small snack dishes. Having worked in Peking-style restaurants in Hong Kong, he settled on a jerky-like beef dish that was sweet and chewy. Unfortunately the guests, used to tender Alberta beef, did not take. “Survival,” writes Hui, “was dependent on winning over white customers.”

Wong did more experimentation before an idea hit him: why not fry the beef? His customers loved fried food. With some batter and less spices, ginger beef was born — a dish so popular that it quickly spread across the Prairies.

As they say in design, form follows function; chop suey wasn’t random after all. And for people like me who thought that “fake” Chinese food is lazy, Wong’s story proves that it takes skill. Wong had to fry the beef with great care to keep it tender, “highlighting the fresh, local beef,” Hui writes. Out of Calgary, a Canadian dish.

Other foods make an appearance in Chop Suey Nation, like the dishes of Hong Kong cha chaan teng cafés, a mishmash of pan-Asian and Western colonial flavours. Hui’s husband eats Korean pizza, with toppings like bulgogi beef and gochujang, a ubiquitous red chili paste. It’s a young invention, but one that’s growing in popularity in American and Canadian Korean communities.

As inventions like these grow deep roots, it poses the question: what’s authentic food anyway?

Hui argues that immigrant-driven cross-cultural creations, often cooked in the face of racial and economic barriers, are a “display of perseverance, creativity and entrepreneurialism.” In the case of chop suey, what could be more Chinese or Canadian?

Leftover thoughts

Two pandas, two menus. I first encountered the two-menu phenomenon in Austin, TX, at a restaurant called Twin Panda. To my surprise, my Indonesian friend Josephine vouched for the place as an authentic Indonesian restaurant. On one menu, fried rice and egg rolls. On the other, beef rendang. I ordered from the Indonesian menu. The fried tilapia was very good.

Chop suey on the lake. Sometime in the late 1970s, my Great-Aunt Ulin’s family had a restaurant called Chinese Kitchen in the central Saskatchewan lakeside town of La Ronge. There was one other Chinese family in the town and they also ran a restaurant, called Chicken Delight. My great-aunt’s family found success feeding the town’s miners for about a decade before they moved back to Vancouver.

The restaurentrepreneur! In recent years, Metro Vancouver has seen the rise of restauranteur-entrepreneurs bringing over big chains and franchises from East Asia. Rather than working-class mom-and-pops, these are educated transnationals with business savvy. Rather than humble fare, the dishes and restaurants being imported focus on high quality and introducing food concepts. There are Chinese hot pot chains like Haidilao and Dolar Shop, the high-end, nostalgic Old Beijing Roast Duck, artisanal bubble tea spots like Yi Fang and The Alley, among many others. No chop suey here.

‘Fame awaits in a distant land.’ Did you know that fortune cookies were inspired by a Japanese, not a Chinese, cookie, called omikuji? It’s hard to pinpoint who introduced the treat to Chinese Americana, but they were popularized in California in the 1920s and have become synonymous with chop suey cuisine. You will not find them in Chinese restaurants in China.

The Vancouver book launch for Chop Suey Nation is Sunday, Feb. 24. Free admission, registration encouraged. Details here.

Read more: Food

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: