[Editor’s note: This is an excerpt from the new collection Symbols of Canada (Between the Lines, 2018), which “gives us the real and surprising truth behind the most iconic Canadian symbols revealing their contentious and often contested histories.” The collection is edited by Michael Dawson, Catherine Gidney and Donald Wright.]

An anthropologist, an artist, and a politician walk into a restaurant and we have a great opener for a joke and a brief summary of how the totem pole became recognized around the world as a symbol of Canada. The year was 1929, the anthropologist Marius Barbeau, the artist Group of Seven member Edwin Holgate, and the restaurant the Jasper Tea Room in the iconic Chateau Laurier. A stone’s throw from Parliament Hill, it was the haunt of many parliamentarians, including the prime minister, William Lyon Mackenzie King.

Admittedly, the totem pole is an unlikely candidate for a national icon. Totem poles existed in relatively few First Nations communities in a sliver of what is now British Columbia and southern Alaska, so remote that even in 1910 they could only be reached by several days’ boat journey north from Victoria and Vancouver; Indigenous culture was considered by many Canadians, including prime minister King, to be “barbaric”; and, finally, totem poles were no longer being carved, and those that survived were in a state of decay, largely because the Indigenous peoples of the West Coast who had carved them were under intense pressure to abandon their culture. (The ceremony needed to carve and raise a totem pole — the potlatch — was actually against the law!) How, then, did these rare and exotic disappearing carvings, many of which were in Alaska, come to be a symbol of Canada?

The story begins in 1913 with the completion of the ill-fated Grand Trunk Pacific Railway (GTPR). The railway, whose president, Charles Hays, went down with the Titanic in 1912, was also sinking under the weight of its accrued debt because almost no one yet lived in the expanse between the northern Prairies and Prince Rupert, B.C., except in small First Nations communities. Looking for sources of revenue, the railway turned to tourism. The GTPR’s route ran along the Skeena River, through the Gitxsan village of Gitwangak (Kitwanga), one of a very few communities in British Columbia that still had a cluster of standing totem poles. Yes, its more profitable competitor, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR), also had grand hotels, as well as sublime scenery, but only the GTPR had totem poles. By 1925, six years after the bankrupt railway had been nationalized as the Canadian National Railway (CNR), the totem pole collection at Gitwangak was considered the most photographed site in Canada after Niagara Falls.

The CNR had a formidable ally in the form of Marius Barbeau, a leading anthropologist at the National Museum of Canada. Barbeau believed that Indigenous people in Canada were dying out and that their monumental art needed to be recorded before they entirely disappeared. Like the CPR before it, the CNR used “product placement” to promote tourism and it invited famous artists to travel for free as long as they painted the scenery the company wanted to promote. Barbeau arranged for the CNR to provide free passage to Group of Seven artists A. Y. Jackson and Edwin Holgate, and he served as their guide in Gitxsan territory in the late summer of 1926. They spent a week at Gitwangak, where Harlan Smith, another National Museum of Canada anthropologist, was working on a government-sponsored project to restore, repaint, and relocate the villages’ totems alongside the railway tracks, where they would be more visible to tourists.

There were many terrible ironies to this project, a collaboration of the Dominion Parks Branch, the National Museum of Canada, the Canadian National Railway, and the Department of Indian Affairs. The standing poles were being made into a tourist attraction, as a reminder of the past glories of an Indigenous culture that the federal government was actively trying to suppress. The Indian Act had been amended in 1884 to ban the potlatch and so suppress Indigenous law and culture. It was amended again in 1914 and 1918 to make it easier to convict British Columbia’s Indigenous people of hosting a potlatch — a feast needed to erect a new pole. Successful potlatch prosecutions between the 1910s and the 1930s included a case in Alert Bay in 1921, in which 22 Kwakwaka’wakw were sentenced to jail time, and another in 1931 in Gitxsan territory, where Barbeau was working, in which two men were convicted and one sent to prison. The 1920s also saw the extension of the federal Indian residential school program and the beginning of the enforcement of compulsory school attendance designed to eradicate traditional culture.

As Indigenous communities came under new pressure and their population reached its lowest point in the 1920s, Barbeau (ignoring Alaska) identified the totem pole as a distinctive new form of art that was uniquely Canadian — a coming together of Indigenous motifs and culture with the European iron technology used to carve them.

Beginning with British explorer James Cook in 1778, visitors have been struck by the power of West Coast Indigenous art forms — including house posts (of which more below) and totem poles. While these monumental carvings existed in various forms before European contact, the arrival of new trade goods and wealth contributed to an explosion of the most familiar totem poles — free-standing outdoor structures — in the mid- to late nineteenth century. By the 1870s, photographs of the Northwest Coast show dozens of these totem poles in front of villages from the Tlingit communities in Alaska, through Haida Gwaii, across to the Nisga’a, Tsimshian, and Gitxsan villages on the Nass and the Skeena watersheds, through the Haisla and Heiltsuk territory, and as far south as the Kwakwaka’wakw villages on northern Vancouver Island and the islands and mainland shore opposite. One Tlingit village, Tuxekan, had 125 mortuary and memorial poles in 1916, while other communities had more than 70 house, mortuary, and memorial poles standing in the late nineteenth century.

What is now called a totem pole is in fact a story, or series of stories, with a range of distinct purposes and cultural styles carved in three dimensions into a tree trunk stripped of its bark. The earliest pictured is what is known as a house post, painted by John Webber at Yuquot with Captain Cook in 1778. These interior carved poles actually supported the roof beams of the traditional longhouse. Using stylized animal or spiritual figures or crests, these poles told elements of the history of the family or clan that owned the house.

The most familiar of the monumental totems is the house pole, sometimes known as a house frontal pole, a free-standing structure set in front of a longhouse and often with a portal that forms the doorway to the house. Like the house posts, these tell stories about the owners’ ancestors, including their deeds, spirit helpers, and clan crests. The poles, according to the Gitxsan and Wetsuweten people, were “the expressions of ownership of land [conveyed] through the adaawk, kungax,[their stories], songs, and ceremonial regalia.” “Confirmation of ownership comes through the totem poles erected to give those expressions a material base.”

The Haida and the Tlingit also erected a third form of totem pole to mark the death of a distinguished family member. These mortuary poles sometimes held the remains of the deceased. The Coast Salish of southern Vancouver Island and the Fraser Valley carved life-size (or larger) mortuary figures that often represented the deceased or his or her spirit helpers. The Kwakwaka’wakw and the Nuu-cha-nulth, on Vancouver Island’s west coast, have historically produced another form of monumental carving: welcome poles, large human figures that stand near the entrance to a village to welcome guests. The final type of pole was a story pole, narrating a significant event or used to shame or embarrass someone who made the owner angry. In that case, the person shamed was often represented on the top of the pole.

Before the arrival of iron blades, power tools, and motorized transportation, the carving of a pole took several years of work, from the planning, the selection of the right tree — almost invariably a western red cedar — then the felling at the right time of year, the hollowing-out on site, followed by the challenges of transport overland and by sea to its intended location, where the design was ultimately carved. The carving alone might have taken a team many months of full-time work depending on the length and elaboration of the design. The poles were often painted and then a trench was dug to plant the pole. Hundreds of people were, and are, required to raise a large pole, with some people pushing and many others pulling on ropes to bring it into a standing position. Pole raising was, and is, typically accompanied by a potlatch at which speeches are given to tell the story on the pole, praise is bestowed on the owners, and gifts are given to the witnesses in attendance who, in accepting the gifts, certify as true the story and right to the images of the family who raised the pole. Only families who had accumulated large surpluses of wealth could afford to pay for the transport and carving of a pole and the feast required to raise it, so poles were also symbols of prestige and status.

Since the very first arrival of Europeans in the Northwest, there has been an active exchange of Indigenous artistic production and Europeans’ industrially produced goods. Indigenous people eager to acquire metal, fabrics, and decorative items traded with sailors eager to have mementos of their visits to the remote Northwest Coast. From the 1820s, Haida were selling elaborate three-dimensional carvings in argillite — a black slate unique to Haida Gwaii — to this small but important market of commercial fur traders and explorers.

The advent of regular steamer service from San Francisco to Alaska in 1883 created an opportunity to capitalize on the unique totem poles still visible from the waters off British Columbia and Alaska. Alaskan visits grew from 1,650 in 1884 to over 5,000 in 1890 as the Pacific Coast Steamship line started to advertise the trip as the “totem pole route” and Alaska as “the land of the totem-pole.” Indigenous carvers met the tourist demand for totems with miniature replicas. The earliest known example was carved from argillite and acquired in Victoria by the photographer Frederick Dally in the mid-1860s. Some miniatures were carved by professional artists such as Haida Charles Edenshaw, who was active between 1870 and 1920. Edenshaw’s replicas, which were over a metre high, are recognized today as exquisite works of craftsmanship.

For museums, full-size totem poles became the holy grail of ethnographic prizes, and collectors rushed to the Northwest Coast to purchase or, in many cases, simply remove poles from deserted villages without permission, as did some Seattleites who, in 1899, stole a pole from Tongass and erected it in Pioneer Square in their city as a “municipal landmark.”

British Columbia was slower to recognize the tourist appeal of the totem pole. In 1903, the Tourist Association of Victoria rejected an artist’s suggestion of “an Indian” for the cover of a promotional book because local prejudice against Indigenous peoples had convinced the association “to avoid using Indians in our illustrations as much as possible.” By the 1920s, things were changing. In Vancouver, the city had expelled actual Coast Salish Indigenous people from their historic village site in what had become Stanley Park, while a group of citizens in the Art Historical and Scientific Association of Vancouver were attempting to create a mock northern Indian village on the same site to attract tourists. They succeeded in purchasing four Kwakwaka’wakw totem poles and erected them on the former Squamish village site, establishing it as one of Vancouver’s premier tourist attractions. In 1936, the association added three new poles, and in 1941 Victoria opened Thunderbird Park, its version of an outdoor totem pole museum, which was also located on a former village site.

The demand for low-cost miniature totem poles for the tourist market exceeded the willingness of West Coast carvers to provide such commodities, and so businesses, like Seattle’s Ye Olde Curiosity Shop, found in the 1920s that they could supply poles carved in Japan from cow bone. Today, the carved wooden totems sold in tourist shops are imported from Indonesia, and resin or plastic poles, cast in standard molds, are sold at almost every tourist shop in Canada, alongside their miniature northern cousin, the inuksuk.

But back to the story of the making of a national icon: in 1927, the year after Jackson and Holgate visited the Skeena poles and, significantly, the sixtieth anniversary of Canadian Confederation, Marius Barbeau co-organized a show with the National Gallery of Canada — the “Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art: Native and Modern” — that brought totem poles to the political, cultural, and tourist capitals of Canada. Prime minister Mackenzie King attended the opening in Ottawa in 1927. The show travelled to Montreal and Toronto in 1928 and introduced both the totem pole and the as yet unknown Emily Carr — whose work frequently featured totem poles — to the national scene alongside the artifacts of West Coast Indigenous people.

“History in Canadian art was made,” wrote the Toronto Globe, “showing what a tremendous influence the vanishing civilization of the West Coast Indian is having on the minds of Canadian artists.” Holgate’s woodcuts, Jackson’s illustrations, and Carr’s new fame all spread the image of the totem as part of the patrimony of Canadian culture and a unique representation of the country. At the same time, Mackenzie King and his colleagues in Parliament were doing their part to erase First Nations from Canada. Having earlier banned the potlatch needed to raise totems, in 1927 Parliament prohibited Indigenous people from hiring lawyers to reclaim their land.

Yet the totem had caught the national imagination. Within a year, the first totem pole to grace a Canadian postage stamp appeared. The pole, the Spesanish (or Half-Bear Den) from Kitwanga, had been copied from a photograph by Marius Barbeau.

But Barbeau was not done. He convinced the CNR to commission Holgate to redesign the Jasper Tea Room in its signature hotel, the Chateau Laurier, in the “Skeena River Indian style.” Opened to great acclaim in 1929, this restaurant in the heart of Ottawa’s cultural and political centre had the pillars designed as faux totem poles, and applied totem motifs to the lamps and other features. Writer Merrill Dennison described it as “the most Canadian room in Canada,” while Barbeau described it as “the symbol of our growing aspirations toward nationhood and a culture that will be our own, our contribution to the world at large.” In the eyes of both the media and the arts establishment, the totem had been bequeathed to the whole nation by a disappearing race.

In the end, the artist and the anthropologist were elated but the politician disgusted. Prime minister King, a regular at the Tea Room, had called the 1927 West Coast Art exhibition “barbaric,” an adjective he also later used to express his view of totem poles. For his role in creating the Jasper Tea Room, King thought Holgate should face eternal damnation.

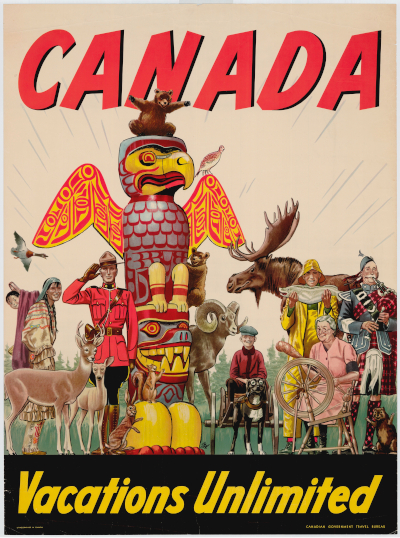

While totem poles had definitely arrived as part of the national imagination, if not a part of the prime minister’s, they had not yet hit the road as Canada’s international ambassadors — but that was about to change. The 1929 opening of the Jasper Tea Room coincided with the onset of the Great Depression and the attendant, and dramatic, drop in tourism. R. B. Bennett, by then prime minister, created a Senate Committee in 1934 to promote tourism. Within months the Canadian Government Travel Bureau was born and in 1935, 50 years since the potlatch had been banned, it published its first promotional booklet. Aimed at American tourists, Canada, Your Friendly Neighbor Invites You had on its cover, among many other iconic symbols of Canada, two totem poles. It was the symbol’s breakout appearance as a piece of national tourist promotional material. Two years later, when Canada created its pavilion for the Paris International Exhibition, a totem pole stood beside the main door.

In Canada, the revival of totem pole carving began in Vancouver in the 1940s with Ellen Neel, granddaughter of the famous Kwakwaka’wakw carver Charlie James. While this had largely been a male pursuit, Neel began carving model poles in 1946 in Vancouver after her husband had a stroke. In 1948, the Vancouver Parks Board offered Neel space for a carving studio and shop in Stanley Park, not far from the “Totem Park.” While Neel mostly carved miniature totems for tourists, including an order of 5,000 from the Hudson’s Bay Company stores, she also carved some of the first new standing poles to be produced in British Columbia in the twentieth century, including a 16-foot pole for the University of British Columbia (UBC) and a large pole for the annual Pacific National Exhibition. In 1949, UBC also invited Neel to restore some poles in its Museum of Anthropology. She did so for a year, but preferring to create her own, she introduced her uncle Mungo Martin to the museum. Martin worked at the museum from 1949 to 1951, when he was hired by Wilson Duff of the British Columbia Provincial Museum in Victoria to restore its poles and to carve replicas.

Martin’s hiring coincided with the removal of the potlatch prohibition from the Indian Act. During the decade that he was chief carver at the BC Provincial Museum, he also carved numerous new poles for the museum, as well as for provincial and federal celebrations. He trained a new generation of carvers, who formed the basis for a renaissance of totem pole carving in the 1960s and 1970s. Martin also formalized an entirely new form of totem that might be called the “Commemoration Pole.” To commemorate the centenary of British Columbia’s creation as a colony in 1858, Martin was commissioned to create two identical thirty-metre poles, one to be raised in Vancouver on the grounds of the Maritime Museum and the other to be given to Queen Elizabeth and raised in Windsor Great Park. To mark Canada’s 100th birthday in 1967, the BC Centennial Committee commissioned 20 poles to be placed around the province. And in 1971, to mark the centenary of British Columbia’s entry into Confederation, more totems were commissioned — this time 13 15-foot-high poles — as gifts to each of the other provinces and territories and one for Confederation Park in Ottawa.

Today, totem pole kitsch, plastic miniatures, and totem emblems are on everything from tea towels to water bottles, and from pepper shakers to Playmobil kits, and they can be found in virtually every tourist shop in Canada. But there is also a new generation of full-sized totem poles — monumental structures commissioned by governments, museums, corporations, and First Nations communities — that serve as towering pieces of art, and which tell a different story than that told by Barbeau and Holgate in the 1920s.

This new generation of three-dimensional story poles celebrates revitalized Indigenous cultures, a recovery from the dark years of residential schools, hopes for reconciliation, and the artistry of new generations of skilled Indigenous carvers. Appropriated by Canada in the 1920s, today they have been reclaimed by First Nations artists, both for their own celebrations and for commemorations across Canada and around the globe.

Now, when an anthropologist, an artist, and a politician have a serious interest in totem poles, they take a short stroll from the Chateau Laurier across the Ottawa River. There, outstanding works from the world’s largest collection of totem poles, the celebrated masterpieces in the Great Hall of the Canadian Museum of History, glare with fixed wooden eyes directly at Parliament, where politicians had tried for so many years to suppress Indigenous culture while appropriating Indigenous art. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: