On a fair summer’s day a century ago, two young single men travelled north from Los Angeles to enlist at the Mobilization Centre in Victoria. They wanted to fight in a war that had been raging in Europe for three years.

One of them gave his profession as actor, though the description was more aspirational than factual. The other said he was a journalist, though he had most recently been employed as a branch manager for a creamery after handling ice-cream accounts as a bookkeeper.

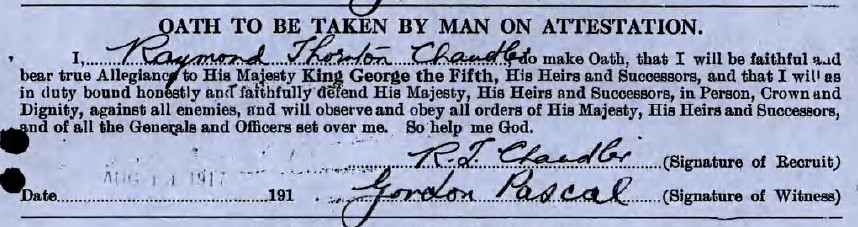

Both solemnly swore to join the Canadian overseas force for as long as six months after the cessation of hostilities between Britain and Germany. They served as witness for each other’s declaration. One signed his name Raymond Thornton Chandler.

One hundred and one years ago today, on Aug. 14, 1917, an obscure writer still decades away from fame as the author of hard-boiled mysteries joined the Canadian infantry to fight the Hun. Raymond Chandler, the creator of the wisecracking, hard-drinking private eye Philip Marlowe, spent less than two years in uniform but the experience, including being knocked senseless by a German shell, profoundly influenced his later writing.

Chandler’s little-known wartime service can be more fully appreciated with the release of 80 pages of his records by Library and Archives Canada. Last week, the archives announced the completion of a five-year project to digitize all 622,290 files of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. (It took 18 months just to remove 260 kilograms of pins, clips, staples and brass fasteners from the files.) Some 30 million images are now available online, including files for Norman Bethune, Lester Pearson and Toronto Maple Leafs’ owner Conn Smythe.

The records add important detail to Chandler’s biography, including his survival after enduring two bouts of influenza during the deadly Spanish Flu pandemic in 1918.

Born in Chicago and raised and schooled in England after his father abandoned the family, Chandler returned to the U.S. in 1912 to seek adventure in San Francisco. His mother joined him a year later and the pair moved to Los Angeles, where a friend found him a job at the creamery. The aspiring writer, who had sold some undistinguished romantic poems to literary journals in England, chaffed at the tedious nature of keeping accounts, yet was obliged to earn enough income to support both himself and his mother.

Two months after the United States joined the Allied cause in April, 1917, Chandler sought an exemption from military service “on account (of) mother,” in the terse language of the registrar who filled out the form. He was her sole support and could not leave her on her own.

The slaughter on the Western Front was so great that Canadian forces were desperate for replacements. The 50th Gordon Highlanders of Canada published notices in newspapers reading, “More men are urgently required by this well known Vancouver Island Regiment to reinforce the Canadian Scottish Battalions at the front.” The notices sought fit men between 18 and 40, promising $1.10 pay per day with all clothing and living expenses covered. Married men were offered a $20 separation allowance. Additional money could be provided by the Canadian Patriotic Fund to maintain a family’s standard of living.

In the San Fernando Building at Fourth and Main in Los Angeles, the American recruiting office was adjacent to one for volunteers seeking to join British and Canadian forces. A headline in the Los Angeles Times read ANGELENOS GO IN STEADY STREAM TO ALLIED CAMPS.

“British-Canadian recruiting office a place of romance and efficiency from which warriors depart in quiet groups, calmly and unsung,” the newspaper stated. The reporter Alma Whitaker noted the Canadians daily sent recruits on a 2 p.m. Pacific Electric train to the waterfront to catch a liner bound for British Columbia.

Joined by his 20-year-old friend Gordon Pascal, Chandler arrived in Victoria to join the Highlanders, one of the “picturesque kiltie regiments” featured by the Times. (Earlier that summer, Chandler wrote a comic operetta titled, “The Prince and the Pedlar,” with music by Julian Pascal, a noted pianist and Gordon’s father. The work was unproduced and forgotten, elusive even to biographers, until the writer Kim Cooper happened upon an online library catalogue entry nearly a century later. As we shall see, Chandler’s relationship with the Pascals became more complicated after the war. The promise of a separation allowance for dependents likely influenced Chandler’s decision to join the Canadians.

The two young men were signed into service by Lt-Col. Charles A. Forsythe, the former commanding officer of the regiment. The officer had been a long-time advocate for the formation of a Highland regiment in the British Columbia capital, a campaign which finally succeeded in 1913 after several failed attempts.

Those who spent a nickel on a copy of the Daily Colonist on the day Chandler enlisted read a front page filled with news favourable to the Allied side. “ARTILLERY IS ACTIVE ON FLANDERS FRONT,” read the main headline.

A lean frame — he stood 5-foot-9 and weighed 140 pounds — did not make Chandler an imposing recruit, though he was in good health with a complexion described as fresh. The examining doctor noted he had dark brown hair and hazel eyes with 20/20 vision. (In middle age, he would be most often photographed wearing glasses and gripping a pipe on the right side of his mouth.) He was assigned regimental No. 2025271.

A family’s sad story was expressed in a few entries on a bureaucratic form. The recruit acknowledged paying his mother $60 per month in support. In the space after the question, “Is your father alive?”Chandler wrote by hand: “I don’t know.”

Maurice Chandler, a civil engineer for a railway and a lapsed Quaker, had married Florence Dart Thornton, an Irish immigrant. They had just one child, born on July 23, 1888. The marriage soon collapsed, largely because of Maurice’s heavy drinking. The boy and his mother lived for a time in Nebraska before they returned to England via Montreal. Chandler enrolled at Dulwich College in south London in 1900. (P.G. Wodehouse graduated that year. The two Old Alleynians, as the school’s former pupils are known, gave the literary world immortal characters in the shamus Marlowe and the butler Jeeves.) Chandler played rugger, suffering a broken nose, and aspired to be a barrister. He graduated in 1906, became a naturalized British subject the following year to qualify for the civil service exam, and wrote for literary journals before returning to North America.

The cadet underwent three months of basic training at Willows Camp, a staging area established on fairgrounds in Oak Bay, just east of Victoria. Years later, he wrote a letter to the journalist Alex Barris reminiscing about his time in the B.C. capital. “If I called Victoria dull, it was in my time dullish as an English town would be on a Sunday, everything shut up, churchy atmosphere and so on,” he wrote. “I did not mean to call the people dull. Knew some very nice ones.”

In November, he was ordered to Halifax, where he boarded the ocean liner Megantic bound for Liverpool. By March, 1918, he was in the trenches near Arras serving with the 7th Battalion of the British Columbia Regiment. Some of the men he fought alongside had survived Ypres and Vimy Ridge.

His papers include a fragment of unpublished memoir in which he describes a gun crewman “silhouetted above the parapet, motionless against the glare of the lights except that his hand was playing scales on the butt of his gun.” Another time, the uneven edge of a trench seemed like “a line of crazy camels in a nightmare against an idiotic moonrise.” The war erased the romanticism of his poetry and added some sharp metaphors to his prose, a trait for which he would come to be celebrated.

Just two months after arriving on the front lines, he was promoted to sergeant and given command of 30 men.

“Once you have had to lead a platoon into direct machine-gun fire,” he said, “nothing is ever the same.” When a German shell landed near his trench, he suffered a concussion, a fate that would befall many of his characters, including his proxy, Marlowe.

He was in hospital with influenza for six days in July and another six days in October. The examining doctor noted “good recovery” after both episodes.

In the fall, he was assigned to the No. 6 School of Military Aeronautics at Elmdale Road Camp in Clifton, Bristol. His Royal Air Force medical form listed his smoking habit as six cigarettes and six pipes daily, and his alcohol consumption as moderate. That would not be the word used later in life, as it was while with the flyers that he discovered the ability to drunkenly crawl into bed only to arise afresh after a few hours, a talent he would come to consider more a curse than a blessing. (“I’m an occasional drinker,” Chandler wrote in the 1939 short story, “I’ll Be Waiting,” “the kind of guy who goes out for a beer and wakes up in Singapore with a full beard.”) The dreary wait to be returned to Canada after the Armistice was signed on Nov. 11, 1918, was eased by long nights of drinking.

At last, Chandler left Liverpool aboard the Carmania on Feb. 1, 1919, arriving in Halifax a week later. He was discharged on Feb. 20, 1919, at Hastings Park in Vancouver. He then crossed the strait to Victoria to catch a boat to San Francisco.

Once back in Los Angeles, he had an affair with the married Cissy Pascal, the wife of the man with whom he wrote the operetta and the stepmother of the friend who joined him in volunteering for the Canadian army. She had an amicable divorce, but Cissy and Raymond did not marry until after the death of Chandler’s mother, who did not approve of his relationship with a woman 18 years his senior.

Starting as a bookkeeper, Chandler climbed the corporate ladder at oil companies before becoming a vice-president with the Dabney Oil Syndicate, only to lose his job during the Depression. He was 45 by the time he sold his first story, “Blackmailers Don’t Shoot,” to the pulp magazine Black Mask in 1933. Philip Marlowe made his debut in Chandler’s first novel, The Big Sleep, which was released by Knopf in 1939. The publisher advertised the book as a worthy successor to Dashiell Hammett’s The Thin Man and James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice. Over time, Marlowe has been portrayed on the big screen by the likes of Robert Mitchum and Humphrey Bogart.

Chandler became a screenwriter, too, gaining Academy Award nominations for Double Indemnity in 1945 (best adapted screenplay) and Blue Dahlia in 1947 (best original screenplay).

The writer was bereft after Cissy’s death in 1954 and spent much of his final years in a drunken stupor before dying of pneumonia in California in 1959. Celebrated as a great noir writer in his day, his reputation among critics and readers has only improved over the years.

Four years ago, a blue ceramic English Heritage plaque was attached to a Victorian villa at 110 Auckland Road in the leafy Upper Norwood neighbourhood of London, where Chandler lived as a day student from 1900 to 1905. As yet, no such marker exists for his months in Victoria, nor his service in the Canadian infantry. ![]()

Read more: Film

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: