Sixty years ago, a new bridge linking Vancouver to the North Shore collapsed during its construction. Seventy-nine ironworkers plummeted into the Burrard Inlet below, and 19 lost their lives.

Today, the Ironworkers Memorial Bridge, better known as the Second Narrows Bridge, stands in the wake of this disaster. Six decades after its collapse, few people are left to share their tales from that terrible day.

In 1958, Peter Hall was working as a draftsman for the Dominion Bridge Company. A hobby filmmaker, he was tasked by the engineering firm to make a movie of the bridge’s construction. Two or three times a week, Hall filmed without the safety of a harness on beams that were suspended hundreds of feet in the air.

On June 17 of that year, Hall had been delayed at the office. When he arrived late to the building site, the bridge had already fallen into the water. Despite losing friends, many of whom were young men just like him, he carried on with his movie until the bridge was rebuilt in 1960. After the bridge’s completion, Hall carefully stored the film reels away. He never showed the film to anyone until journalist George Orr caught wind of its existence last year.

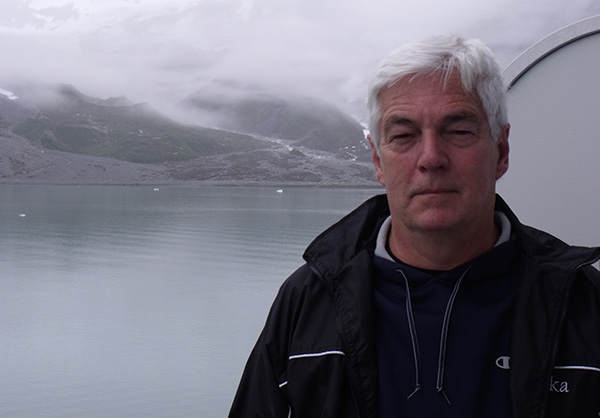

Orr got his start in Vancouver daily news in the 1970s. Over the span of his career, he transitioned from radio to broadcast journalism and finally to teaching at BCIT. His latest film about the collapse of the Second Narrows Bridge, entitled simply The Bridge, is his fourth documentary.

“I like long stories that take a long time to shoot that tell complicated projects in simple terms. That’s what I do,” Orr said.

The Tyee spoke with Orr about uncovering Hall’s 60-year-old footage, and befriending the octogenarian in the process.

The Tyee: When did you discover that Peter Hall had this archival footage?

George Orr: Last summer, I read an article in the Parksville Qualicum Beach News about a fellow in a retirement home. At the end of the article, [Peter Hall] mentioned that he’d done some filming around the Second Narrows Bridge while it was being built. So, I phoned him up and said, “What did you do and what’s happened with this film?” He said, “I’ve shot 3,000 feet of 16 mm, high-quality, colour film. Nobody has ever seen it.” And I thought, “Well, they will now.” We’ve been working on it ever since.

And that was it — you knew you had to make it into a documentary?

Well, it was too good to be true. You hear about these sorts of things in the movies: the undiscovered treasure. Well, I found one.

Had you known about the collapse of the Second Narrows Bridge by that point?

I did. I knew of the bridge, but the stories were all old newspaper photographs and a plaque beside the road. Until this came along, I had never given it any thought.

Besides Peter Hall’s footage, was there another reason that made you want to devote an entire film to this event?

I worked on another project over the course of 10 years about the coming of the Olympics and the changing face of Vancouver, which is yet to be finished. In the process of doing that, I videotaped the 50th anniversary of the collapse in 2008. I put the footage away and didn’t give it any thought — I’ve got a lot of archived footage — until this material came up and I thought, “Well, I’ve got something I’ve shot and I’ve got this stuff.” So, I started looking for people whose stories I could tell that wouldn’t just make this a piece of history, but something more dynamic.

You have a variety of characters in your film — a disc jockey, a commercial diver, a news reporter, a longshoreman — how did you find them?

It was just serendipity. I’ve got a good friend named George Garrett, an ace reporter in Vancouver for 43 years, long since retired. I was having lunch with George, mentioned the footage, and he said, “That was my first big scoop.” He told me about that and then he told me about his friend who had been an investigator on the bridge and that led to [disc jockey] Red Robinson, who recalled being on air, who actually kept the tape of being on air. It was just kind of serendipity. I didn’t really dig hard to find these people, they just appeared. It’s kind of like this film really wanted to get told.

Can you explain why the bridge collapsed?

They were building from the North Shore and the south shore simultaneously and the bridge coming out from the North Shore had to be a big arch. They had to cantilever out a lot of steel in order to meet up with the other side. As they’re doing that, they put in what were called temporary supports to carry that weight. It turned out that because those were not part of the permanent structure of the bridge, they were not certified by the engineer. So, they were put up, they thought they’d be fine. [But] there were a couple of mistakes made in the mathematics of the steel working. Nobody caught them because it wasn’t the certified-engineer part of the bridge, because it was temporary. That’s what happened: they failed. It came down and 79 men were working on the project, and as a result of the project, 19 of them died.

Do you have a visceral reaction when you see the footage of the bridge crumpled in the water?

I did initially. When I looked at [the archival film] it was overwhelming. It was just the raw camera footage of being up on the bridge, seeing these people working, seeing down 200 feet, they’re not wearing safety harnesses or belts at all. Initially, it was overwhelming. Then I started processing it and I had to turn footage into a story and create the narratives and connect the characters, and so I became numb to it after awhile. Until I started showing rough cuts to friends and looking at their faces and I go, “Oh my Lord.” The potency of it is coming back for me. I have yet to see it on a big screen and I’m quite unnerved by that prospect.

The film is really powerful when we hear some of the survivors, like Gary Poirier, tell their stories from that day.

Gary was an 18-year-old kid. He’d just gotten into ironworking. When you watch the footage, he’s very emotional. He relives that moment every day, and has for the last 60 years. When I found him, he wasn’t really interested in exploring his emotional vulnerabilities on camera. So, he and I got to know each other, and I tried to convince him of the value of this. When he finally saw the piece in a screening exercise he looked at it and he cried and said, “I’ll be remembered.” I found that really quite overwhelming and powerful.

Did you have any long-harboured fascination with the subject matter of this film, like engineering or labour?

In the ‘70s, when I worked at CKNW, I covered labour for a couple of years. I lived part-time in the labour journalism world and got to know the men and the women who were working in those fields as activists and organizers and picketers. So, it was a milieu I was comfortable with. The great thing about journalism is [you] pick a project and learn as much as you can in the time allotted. If you’re working in daily news, you don’t get to scoop up a lot of context. But with a project like this, I talked to all sorts of people. I know more about engineering than I ever thought I would. I’ve scratched the tip of the iceberg about what there is to know about it. It was fascinating because I had never really given any thought to, “How do you make a damn big bridge stand up?” Now I know more about it than I want, I think.

The film focuses a great deal on Peter Hall. How did your relationship develop through the process of making the film?

When I phoned him and asked about the footage, he was very candid, very pleasant, very soft-spoken. He was a little taken aback that I was interested, but I went to visit him, we talked, and since then he took on faith that I kind of knew what I might be doing. I took the footage away, I chewed on it for about six weeks — I’d interviewed him a little bit already — and [when] I sent him a rough cut, he was kind of blown away about what might become the story. But he kept on saying, “It’s not about me.” And I kept on saying, “Well, a strong story has an interesting spine of characters who we watch move through time. So yes, Peter, it is about you.” So, he and I became close friends. We’re 20 years apart in age, but we’re good friends. I told him I was going to make his film famous. He’s getting something of a public profile in his 86th year, which I think is delightful.

What was it about Hall that grabbed you and made you want to build the film around him?

Well, to be honest, you could look at old footage for two or three minutes and go, “Well, that’s interesting, I guess, but what does it tell me?” A good story needs a strong character. Peter, he’s an honest man, he’s not blowing his own horn at all. He’s an engineer by trade — he’s a numbers guy and a slide-rule guy. Through listening to Peter — you’re looking at an 86-year-old man, but you’re actually hearing a 26-year-old man, who’s got a camera for the first time, who’s come out from Britain and has discovered the New World and has started making his way in life. So, you experience the story through him and I think that’s part of the strength of the story.

Has the film become an obsession?

Oh, yeah. I’ve been at this documentary business for 20 years, and I’ve yet to make 10 cents out of it. CBC’s carried one of them; this one’s going to get a bit of traction educationally. I’ve been more than obsessed about this stuff for about 20 years. I think I’m finally running out of steam, but then you open the paper and you read something or you hear something and you go, “Wow, that’s an interesting story.” If you push it, it will become interesting. If you just walk away that won’t happen. I’m still looking for the next story.

Do you expect Vancouverites to be familiar with this story?

Everybody over 65 who was born in Vancouver knows this story. I hear from dozens of people every day: they were in school [when] they heard the bang, or they heard the sirens go by, or they had an uncle who died. So, everybody over 65 knows where they were when it happened. Everybody under 40 really has no idea. Part of my process in doing this is to keep this piece of history alive, to bring it back to life, so that it doesn’t get forgotten, because it was horrible. It helped build up the North Shore and it helped develop the region. It was the last link of the Trans-Canada Highway that was built in the ‘50s across the country.

Vancouver has not really embraced its history. I’m hoping through processes like this, and other people who do this kind of work, to get this city to a point where some day when it starts to look back, there will be things to look back at. And this will be one of those things. It’s important, and we’ll see what kind of audience it attracts.

What’s next for the film?

There’s going to be three screenings at the Vancity Theatre. We’ll push the button at approximately the moment when the bridge collapsed. Now that I’ve got the material and processed it and put it together, I’ll find a variety of homes for it so that it can be part of the memory of this place. I’ve had interest from local museums to create something more educational and shorter. What I will do with all this footage, I will produce in a variety of formats for provincial archives and city archives. I told my kids years ago with these projects, “I’ll shoot them, I’ll cut them, I’ll do something with them, and when I pass, you’ll look in my sock drawer and there will be all these great stories.” So, this one goes in the sock drawer along with all the rest.

Will you be able to let go of the film after you’ve screened it?

You never finish a piece — you just walk away. That’s the thing about journalism, period. It’s never perfect, but you get to a point where you go, “I’m tinkering here, I’m puttering, I’m dealing with the swapping of verbs.” Whatever level of detail you get to, at some point you have to walk away. I could re-edit the whole thing, but my wrist hurts and the way it sits now — it’s fine. To re-edit it wouldn’t make it better, it’d just make it different. I’m not looking for the next project, but the way my project life has worked, one finishes and one rolls along and goes, “What about me?” You never know.

‘The Bridge’ will screen on June 17 at the Vancity Theatre, 1181 Seymour St., at 3:30 p.m. A ceremony to remember the 60th anniversary of the bridge’s collapse will precede the film at 1 p.m. alongside the Ironworkers Memorial Bridge. ![]()

Read more: Transportation, Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: