There was a time when I assumed that one day, the sirens would sound, the missiles would rain down, and it would be sayonara, suckers!

But as curator John O’Brian stated in his introduction to Bombhead, a new exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery, the idea of nuclear annihilation largely disappeared from the public consciousness. “We forgot to be afraid. Except for artists, who are always paying attention.”

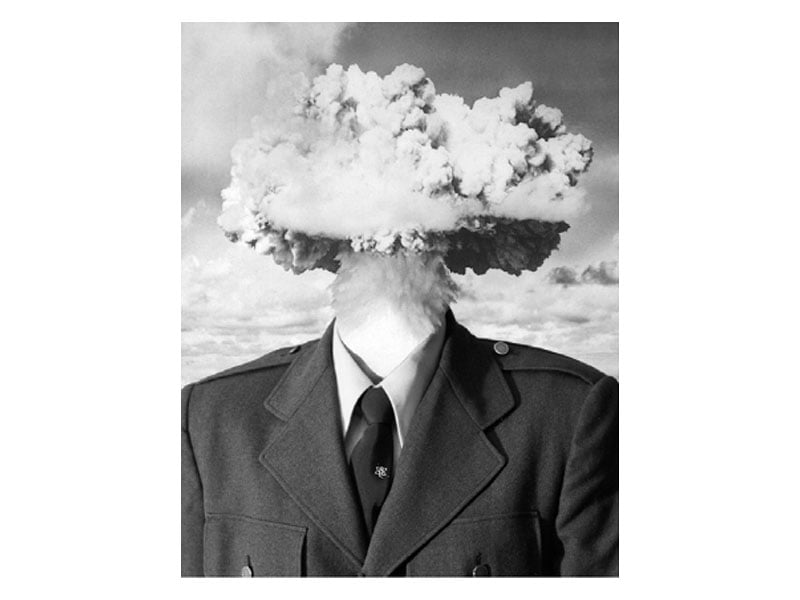

The title of the show pertains to the iconic mushroom cloud extruded by an atomic detonation. It is a peculiar shape — part skull, part horrifying chrysanthemum — familiar to anyone whose been around since 1945 or so. But the image has new relevance, vaulting out of history to take centre stage in nightmares and headlines around the globe. (They are often the same thing at the moment.)

If Vladimir Putin’s recent grandstanding is to believed, the nuclear monster is back with a bang. The Russian president just announced a broad range of weapons, sparking the idea for a new arms race. And if that weren’t enough, the spectre of a couple of corpulent madman with their stubby fingers poised over the nuclear button also seized media attention and twitter feeds. As the U.S. and North Korea taunted each other with schoolyard threats about the size of their armaments, the whole world, went “uh oh…”

It would be kind of darkly humorous, except for the fact that total Armageddon puts a damper on the super fun times.

So, it is a fitting moment for the launch (heh…) of Bombhead at the Vancouver Art Gallery, a show that could very well be subtitled: “The Bomb Rides Again!”

The recent incident of Hawaiian residents being advised that missiles were on their way brought back childhood memories of bomb drills in elementary school in the city of Little Rock, Arkansas. At the time, I didn’t have much of a sense of what was really happening, only that it was bad, and largely inescapable. No matter how well you hid under your desk, with your arms crossed over your head, it would find you and blow you into dust.

I don’t remember when that particular fear was replaced by other more immediate catastrophes — environmental collapse, global pandemics, what have you. But the bomb lingers long in the legacy of film, art, and culture-making shaped by this sense of imminent doom.

Guest curator O’Brian stated that he was initially skeptical that there would be enough work to build an entire exhibition. But lo and behold, there was whacks of stuff in the VAG’s own collection, some of it, like the work of Bruce Conner, direct and blunt in its presentation, while other pieces take a more oblique approach. In Roy Kiyooka’s series of large-scale photographs Stonedgloves, abandoned gloves appear like dead birds, littering the ground, strange remnants of their human hosts. The implications are more powerful for their quiet and stillness.

Each of the artists in the Bombhead exhibition — David Hockney, Jenny Holzer, Gathie Falk, Betty Goodwin, Robert Keziere, Carel Moiseiwitsch, Robert Rauschenberg, Nancy Spero and Barbara Todd, to name just a few — have their own individual takes on the nuclear reality.

But one artist who was really paying attention to the bomb was Takashi Murakami.

The bomb figures large in the Murakami exhibit, winding its way through his early work with its bleak depictions of a dark, obliterated world, peopled only by shadowy figures, and nuclear reactors, before exploding into the candy-coloured mushroom clouds that currently grace the alcoves in the VAG’s central rotunda. As the essay that accompanies The Octopus Eats Its Own Leg explains, Murakami belongs to the generation of artists who were forced into direct reaction to the legacy of the atomic bomb. As Murakami’s mother liked to remind him, the bombs that wiped out Hiroshima and Nagasaki didn’t fall that far away from where the artist lived as a child. You can also see this lingering half-life in the work of filmmakers like Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata.

Another reaction to the atomic devastation visited on Japan can be witnessed at the Vancouver International Dance Festival this month with various Butoh performances.

O’Brian spoke at length about the decision to include so many different kinds of creative reactions to the bomb, terming it, “The visual culture of the modern era.” Whether overtly or not, the films, drawings, and installations in the show contend in a multiplicity of ways, from the visceral, confrontational work of Nancy Spero to the more cool depictions of weaponry in the work of Carel Moiseiwitsch. Spero’s drawings resemble a body exploding on paper, the violence not only in the subject depicted, but in the ferocity of the lines themselves, virtually carved into the surface, in colours that resemble dried blood. Spero’s Bomb and Victims (1967) is pretty much a combat image filtered through the heart and lungs of the artist.

To be frank, this is not an easy show to contemplate. It opens up a window in the mind that has been sealed shut for a time, and the experience is, to put it mildly, disquieting.

Most of the work dates from a generation of artists that grew up under the threat of imminent nuclear destruction, Generation X-plode we’ll call them. But what does Bombhead contribute to the new atomic age, that we now find ourselves in?

Perhaps just the longevity of the thing itself, resurfacing in different ways, and in different parts of the world. Even here in peaceful old Canada. (Canada has a long and tangled history with uranium and was, until quite recently, the world’s largest producer of the stuff.)

One of the most compelling aspects of Bombhead is its dedication to activism. As long as there has been the bomb, there have been pesky, truculent little humans, busily fighting back with protests, artwork, and encampments, anything to throw a spanner in the works of the Industrial military complex.

Here again, there is a Canadian connection.

In Vancouver, the founding of Greenpeace was sparked by Vancouver Sun writer Bob Hunter, who cobbled together a bunch of raggedy hippies and an old fishing boat to set sail for Amchitka Island to stop the nuclear tests taking place there. The initial mission was documented in glorious black and white images by Robert Keziere. If you want a more detailed version of this story, watch Jerry Rothwell’s film How to Change the World.

The term used by Hunter for Greenpeace protests, was “mind bomb,” meaning an idea that would imbed and implode in human hearts and minds.

It’s a concept that surfaces large throughout the exhibit, but nowhere more epically and explicitly than in Bruce Conner’s film Crossroads. The VAG created a black box theatre to house the film, and it is worth a visit simply for the experience of witnessing the raw power of Conner’s work. Crossroads was constructed from the declassified footage of the first nuclear test that took place near the Bikini Atoll in 1946. The explosion was filmed from dozens of different angles, captured with drone shots, and the result is mesmerizing.

As the Guardian article explains, there weren’t any words that could truly contain or conceive of the power of the bomb. J. Robert Oppenheimer summed it up best in his infamous speech. Ranged against such Godlike destructive power, puny humans look positively insignificant. But people, when they work together, are like army ants, capable of overcoming unspeakable forces simply by keeping on.

In the case of the women of Greenham Common, you could call it an army of aunts. Grannies, sisters, aunties, and children camped out in the mud in England’s green and pleasant land to bring attention the anti-nuke movement. The women of Greenham Common, bravely and beautifully depicted in photographs, can be seen in action in Beeban Kidron’s film Carry Greenham Home. The film is well-worth seeking out to witness what ordinary, albeit, very determined women can do.

There are a great number of other compelling works in the Bombhead show, including Erin Siddall’s film Fukushima Half-Life, and Blaine Campbell's photographs of the particle accelerator centre at UBC’s TRIUMF.

In a moment when arming everyone — teachers, soccer coaches and lunch ladies — is being proposed in the U.S., the biggest weapon of them still has the power to shock and humble.

Even the briefest glimpse of what we humans have fashioned, the ability to unmake everything in a flash and a roar is enough. The most terrible thing about it is how strangely beautiful it is. Watching the multiple explosions in Bruce Conner’s film, creates a curious longing, to see it again and again.

Bombhead runs from March 3 to June 17 at the Vancouver Art Gallery.

If you’d like something a little more upbeat than the end of the world, a Wikipedia Edit-a-Thon is happening at the Belkin Gallery on March 10. The event, offered in collaboration with the UBC Department of Art History, Visual Art and Theory instructor Christine D’Onofrio, and Art+Feminism, brings together different communities (artist, activist, academic) to reinvest Wikipedia with a more inclusive approach, literally rewriting women back into the picture.

The Edit-a-Thon takes place at the Belkin Gallery from 12 to 5 p.m., and is preceded by a How-to workshop at the Koerner Library from 11 a.m. to noon. Other Edit-a-Thon events are also being offered at Emily Carr and The Western Front, but if you truck it out to UBC, you can check out Beginning with the Seventies: GLUT at the Belkin.

GLUT is the first of four exhibitions planned for the Gallery that dig deep into an era of major social movements, including women’s rights, the environmental movement and the LGBTQ movement. The selection explores the beginning of '70s feminist art practice with work from Allyson Clay, Judith Copithorne, Gathie Falk, Jamelie Hassan, Germaine Koh, Laiwan, Sara Leydon, Divya Mehra, Adrian Piper, Kristina Lee Podesva, Anne Ramsden, Evelyn Roth and Elizabeth Zvonar. But more critically, the exhibition also offers continuity with the work of younger artists, and like any seminal feminist experience, it all begins with the written word.

The show packs some serious surprises, including the work of Sister Corita Kent, an American nun who worked with John Cage, as well as other luminaries of the American avant garde

Kent’s art is a potent reminder of the necessity of ensuring that women artists and their work don’t fall into the cracks of history. Once compared to Andy Warhol, she remains little known at the moment.

I am embarrassed to say that I’d never heard of Corita Kent before, and now I am a bit obsessed with her.

Both Bombhead and GLUT are beautifully thought-through and well-executed, and most importantly they make clear what art is capable of when it’s not just hanging over someone’s couch. Who else but artists could remake the world, after we’ve blown it to kingdom come. ![]()

Read more: Film

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: