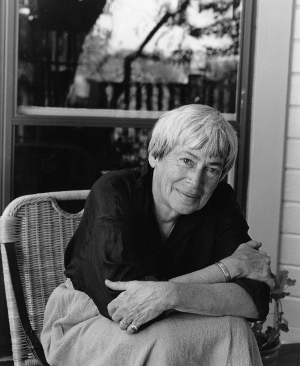

Ursula K. Le Guin has died at 88. For news that might have been expected, it still came as a shock, and one felt around the world. Her name instantly trended on Twitter, with posts in Korean, Japanese, Spanish, Portuguese and Turkish.

It was a personal shock as well. I first heard of her 50 years ago, when I learned that her novel A Wizard of Earthsea and my children’s book Wonders, Inc., would both be on the fall 1968 list of Parnassus Press. A few years later I wrote her a fan letter about Wizard; she wrote back saying she’d been reading my book to her kids.

A Wizard of Earthsea shaped my own writing career. Her ocean world, studded with strange islands, inspired the Gulf of Islands — the Salish Sea, 10 million years from now — in my novel Eyas. And my hero’s journey into Hell was a homage to Le Guin’s Ged and his journey through the land of the dead.

More importantly, Le Guin almost instantly established herself as the only grownup in the field. Science fiction and fantasy were genres derived straight from teenage boys’ dreams of teenage-boy glory, with hot weapons, cool spaceships, and a princess as the prize.

Le Guin cooled our jets in 1969 with The Left Hand of Darkness, about a world locked in ice and populated by humans who become male or female for about five days a month; one can be both a father and a mother. The ambassador from Earth is called “the pervert” because he never quits being male. Half a century later we are still trying to come to terms with what she understood then.

Other books challenged other complacencies. The Dispossessed describes twin worlds, Urras and its moon Anarres — the first a capitalist, class-ridden culture and the second a colony of collectivist anarchist refugees who are taught as children not to “egoize.” Canadian man of letters George Woodcock, himself a philosophical anarchist, thought it was the greatest book on anarchy ever written — and it describes anarchy in decay.

Variations on the theme of humanity

Le Guin was fortunate in her parents, both well-known anthropologists, and she showed us startling cultural variations on the theme of humanity instead of starships swapping laser fire. Her stories were, of course, about our own culture, which she made us contemplate in uncomfortable ways. “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” is about a utopian city where everyone is happy except for one child, whose endless torture supports the city. Most accept this; the ones who walk away are those who will not tolerate happiness on such terms.

Once I had the honour of having dinner with Le Guin and her husband Charles when they were visiting Vancouver. We talked shop, but the part of the conversation I remember best was when I mentioned John Le Carré and she erupted. How could the man be so pessimistic and defeatist, she demanded. She was truly scandalized by a man who might fight but expected only defeat. As she writes in The Dispossessed, “You cannot buy the revolution. You cannot make the revolution. You can only be the revolution. It is in your spirit, or it is nowhere.”

Le Guin did not mellow with age. When a self-appointed militia, all beards and rifles and cowboy hats, took over the headquarters of a national wildlife refuge two years ago, she damned them as “Right-winged looneybirds,” and the media for being “a mere mouthpiece for the scofflaws illegally occupying public buildings and land, repeating their lies and distortions of history and law.”

Le Guin never took the status quo as unchangeable. “We live in capitalism,” she wrote. “Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art, and very often in our art, the art of words.”

For half a century Le Guin’s novels, short stories, and essays appeared like flares on a stormy night, and several generations of writers guided themselves by her light. When she wrote, she gave permission for them to write as she did, and to go beyond her.

And they did. One of the great consolations of my old age is to see the astonishing writers Le Guin has inspired. She broadened and deepened science fiction and fantasy into much more than mere genre fiction, and they have continued her work.

For all the magnificence of Ursula K. Le Guin’s own work, her literary daughters’ work may be her greatest legacy. Thank you, ma’am. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: