- On Some Faraway Beach: The Life and Times of Brian Eno

- Orion Books (2008)

Everybody, when they talk about Brian Eno, talks about his brain. Let's agree it's a large, unavoidable and very attractive organ, and move on down to talk about his groin for a moment.

David Sheppard's book about the life of the groundbreaking composer, producer and artist is the most comprehensive so far. Surprisingly, I can find only one other previous attempt to biographize the man -- and its main revelation to me is what a shag-monkey the man was in his heyday. For several decades, he's presented a cerebral image as popular music's most famous studio boffin and theoretician -- a clean-lined, monkish figure alternating stints in the studios of increasingly dodgy rock bands with appearances at esoteric art gallery installations.

I bought my first Brian Eno record in 1978 entitled Before and After Science. I was 14, and I hero-worshipped Eno for that record, wildly impressed by both the somber image of the brainiac on the cover and the heady talk of something called "Oblique Strategies" on the back of the album. Sex was definitely heavy on my mind at the time, but I didn't connect the hormones racing through my brain and body with this austere figure and his puzzling, intriguing music.

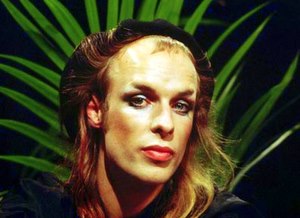

But travel back to 1973 and the inside fold-out cover of For Your Pleasure, the second and last Roxy Music album he appeared on as a full band member, and gaze upon the glammed-out glory of what Lester Bangs once called "his flutterlashed amphetamine spider look". Or hunt down Youtube clips of that early, bug-eyed version of the band performing its deconstructed pop-art-rock live, and you'll see just what an androgenously satyr-like figure the man was.

As Sheppard records, during his early rock star phase Eno was more than eagerly involved in all the usual sexual excess of that period and milieu, cutting a rampant swathe through the groupie hordes, collecting candid Polaroids of his conquests and dropping references to bondage and watersports during his frequent interviews. If you're strong of stomach, visit Enoweb and track down an interview from February, 1974, written by a clearly horrified pre-Pretenders Chrissie Hynde for the New Musical Express. Entitled "Everything You'd Rather Not Have Known About Brian Eno," it reveals the 25-year-old star as a full-blown, toe-curlingly louche perv wittering on about his porn collection -- and it includes this exchange:

"'Can I show you my pubic area?' (!!!) He exposes his stomach down to his, ah -- about six inches below his navel. 'Absolutely bare! Now I've got this beautiful bare belly! I've got this new Japanese thing, you see and the Japanese don't have much hair on their bodies. Japanese culture I tip as the next big thing.'"

Certain proclivities

Well, he was young, and it was the 1970s. And Sheppard exhumes quite a lot of this stuff, including a great, unpublished piece by the aforementioned Lester Bangs, who spent time hanging out with Eno in the post-punk world of downtown New York circa 1979. (You can find the article here). Bangs' lengthy profile -- which is excellent, by the way, and appears often in Sheppard's book -- strikes familiar notes of Eno as an eminently clubbable man, genial thinker and engaged theoretician. But again, the musical monk lifts up his robes:

"My friend and I were sitting [in Washington Square] discussing the comparative merits of various current purveyors of sonic aggravation, when suddenly I looked up and said, 'Hey, isn't that Brian Eno walking this way?' Sure enough it was: blonde hair already balding at thirty, alert blue eyes, sensual mouth, and functionally simple but expensive clothes.

"He came and sat down, cheery as ever, with that bemused expression whose innocence can make him seem, at various moments, like a seraphic artiste or cherubic child. Every time a pretty girl walked by, his head would swivel and he would comment admiringly, like either a kid at a parade or a guy who'd just got out of prison. I mentioned that I was getting ready to do a story on prostitution, interviewing call girls from a midtown agency that advertised in Screw, and he said: 'I called for a girl in response to one of those ads once. It said 'Unusual Black Girls.' So I phoned and said, 'Just what do you mean by unusual?' They said, 'Just what did you have in mind?' I said, 'Well, I'd like one that was bald with an astigmatism.' 'Well, we'll see what we can do,' they said. They found the astigmatism but not the baldness.'

"'Why astigmatism?' I wondered. He answered, 'I'm terribly attracted to women with ocular damage.'"

Indeed, when I went back and listened to some of Eno's best and most influential works, which I still play regularly -- the four early solo records, the production and collaboration with David Bowie and the Talking Heads, the experiments with Robert Fripp, the Krautrock explorations, even the more successful ambient stuff -- I started to think that maybe sex was Eno's secret weapon. There's a throb of lust that runs through this music of the head and keeps it compelling and vital.

'Dead from the neck down'

As usual though, Eno is his own best critic, and he's gotten there ahead of me:

"I think the trouble with almost all experimental composers is that they're all head, dead from the neck down. They don’t trust their hearts, I think, and tend to take themselves with a solemnity so extreme as to be downright preposterous. I don't see the point, really. I've always abandoned pieces which succeeded theoretically but not sensually."

Few artists have regularly offered such clear-eyed self-analysis (Eno on the instrument he is best known for: "Computers are hopeless! They're so under-evolved! Of course, they offer the promise of the future of music, but Jesus, they're badly designed! The fact that three million years of muscular evolution should end up being translated into an index finger clicking a mouse -- this is the problem. Think of any analogue instrument: playing a guitar, for instance, you're doing at least six things at once. I believe musicians have shrunk to fit the pathetic nature of the interfaces.")

Eno is famous these days -- he's got that odd sort of celebrity that's hard to pin down -- as the man who took stadium bands like U2 and Coldplay to art school, who leavened their crowd-pleasing antics with left-field sonic experiments. But Sheppard's book unpacks all the other, more compelling reasons any fan of contemporary music should care about him: his realization that "the evolution of electronic instruments and recording processes had created a situation where the whole question of timbre -- the physical quality of sound -- had been opened up wide and had become a major focus of compositional attention"; the development of ambient music; the introduction to pop culture of ideas inspired by Anthony Stafford Beer's cybernetics theories; the creation, along with artist Peter Schmidt, of the Oblique Strategies cards (an inspirational series of koan-like cards that offer gambits for getting out of creative roadblocks: "Honor the error as a hidden intention" is perhaps the best-known. "Try faking it!" is another.)

Blue sky or just BS?

Sheppard can be an annoying writer. He suffers from advanced mojo-magazine-itis, attempting to mimic his rock'n'roll subjects' flair with an overactive, pun-heavy prose style that just gets in the way of his reportage. But he talks to almost all the right people, including Eno's most insightful critic -- Eno himself -- and focuses, as far as this fan is concerned, on the most interesting period, from Roxy Music up to the post-punk days in New York.

He also doesn't shy away from the fact that Eno is as much an artist of bullshit as any other medium. Friends and collaborators from Gavin Bryars to David Bowie are quoted as enthusiastic allies, but are also allowed to express their reservations. The man has floated a thousand theories, is a veritable blue-sky machine, but has the faint air, common to many futurologists, of a used-car salesman. Many of his ideas -- like his '90s obsession with perfume, during which he once appeared for an interview swirling and sniffing a twig of lavender -- were silly, dead-end, or just gassy gusts of wind (so far, anyway: maybe there's an olfactory revolution in the flailing music industry's future).

But the fact remains that much of what he thought, said and put into practice in the many sectors of pop culture hadn't been done before, or at least not as successfully, or with such clarity. "It's like seeding a crystal" he tells an interviewer. "You start it off and hope that something accumulates around it. When you put a record out, you're hoping that people will pick up on it and take things more seriously than you ever did, and in turn make something much better than you ever did. It's like Music For Airports -- if that hadn't had crystals growing around it, I wouldn't think about it once. I've done stuff that didn't crystallise like that, and it's just forgotten."

Termite Art

This constant seeding, churning and remake/remodeling of ideas make Eno a prime example of what the film critic Manny Farber called "Termite Art", way back in 1962:

"Good work usually arises where the creators ... are involved in a kind of squandering-beaverish endeavor that isn't anywhere or for anything. A peculiar fact about termite-tapeworm-fungus-moss art is that it goes always forward eating its own boundaries, and, likely as not, leaves nothing in its path other than the signs of eager, industrious, unkempt activity ... a buglike immersion in a small area without point or aim ... concentration on nailing down one moment without glamorizing it, but forgetting this accomplishment as soon as it has been passed; the feeling that all is expendable, that it can be chopped up and flung down in a different arrangement without ruin." (Farber contrasted this style to something he called "White Elephant" art, which perfectly describes much of Eno's big-ticket work with U2, Coldplay and the like: "Masterpiece" art pieces that cry out their significance with every earnest inch of their being.)

Eno, of course, has left plenty in his path (if you haven't heard his solo work, start with his masterpiece, 1975's Another Green World). Termite, white elephant, monk, boffin, bullshit artist, priapic rock star: if there's a life in the art of the twentieth century that I'm jealous of, it's Brian Eno's. No one has been more generative and pleasant while providing such movement, cash, and thought-provoking music. Eno may have clipped his plumage since his brief period as an androgynous glam-rock stud, but he's still a rare bird. ![]()

Read more: Music, Gender + Sexuality

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: