[Editor’s note: This is part two of the annual Harvey Stevenson Southam Lecture delivered by Tyee editor David Beers to a full auditorium at the University of Victoria on Feb. 7. The talk was video recorded and can be viewed above. Part one is here.]

The crisis in Canadian journalism, as I discussed in the first part of this talk, is decimating newsrooms and depriving citizens of vital information. Which raises natural questions.

Might crisis create opportunities for innovative publishers in tune with emerging markets?

If grafting giant legacy media chains onto the internet hasn’t worked well in Canada, does that not leave open the potential for some tech savvy entrepreneur to start from scratch to build a sustainable journalism model?

And wouldn’t the most likely opportunity lie in local news, where the retrenchment of Big Media is leaving the market open?

That was the thinking behind the launching of Overstory Media Group in Victoria in 2021 by multimillionaire tech investor Andrew Wilkinson — a story that made this headline in the Guardian newspaper.

A journalism school drop-out, in 2019 Wilkinson already had launched Victoria’s Capital Daily — which became the flagship for Overstory as the company set an ambitious three-year goal of starting or acquiring 50 publications and employing 250 journalists serving small to mid-sized metro regions across Canada.

Wilkinson explained he loved reading the New York Times and wanted to figure out how to pump that kind of reporting back into Victoria and other lightly served communities.

Here was a tech star who said he loved journalists!

Wilkinson’s experiment was watched very closely be me and anyone else itching to know whether public interest journalism was still the sort of profit-making business that could attract venture capital and turn a profit in Canada.

There was plenty of reason to think not. In the U.S. hundreds of millions have flowed into such ventures as Huffington Post, Buzzfeed, Vice and other flashy news sites — and just about all have either foundered or failed to meet financial expectations.

Me, well I’d long ago come to the conclusion that The Tyee should be a non-profit stand-alone, anchored by its special relationship with its members who provide, through monthly contributions of $15, the bulk of our revenue.

We at The Tyee had seen that angel investment — philanthropic contributions really — by wealthy patrons of journalism were also key to our survival.

We could not be where we are today without the stewardship of patrons Eric Peterson and Christina Munck.

We have tinkered for two decades with our model, which also includes arm’s length funding from government and foundations and yes, some advertising. After all that, no one could look at The Tyee and see a template for quickly establishing 50 siblings across the nation. We are a product of our distinct ecosystem and we are, in my mind, not a model for market players.

Instead, we should be viewed as a plucky response to obvious market failure.

Now, in Andrew Wilkinson, here came a business person obviously wiser than I, pouring millions into Overstory and declaring, as of last year, that Capital Daily reportedly already was making a profit.

And they were doing it by publishing in-depth journalism in the public interest, so well-honed that usually there was just one major piece a day.

Part of their model was to push that original content out in a buzzy email newsletter that curated the significant work of other news outlets and listed briefs about doings at city hall and ways to have fun. Hey, if it worked, there was hope after all.

In January, Wilkinson and Overstory CEO Farhan Mohamed announced the layoff of Capital Daily’s editor and three top reporters, saying the numbers no longer worked, projected losses loomed too large. Remaining staff are said to be reeling. Reportedly, a shift in editorial content is in the offing. The jury is still out of course, and I am rooting for an Overstory rebound.

But if Wilkinson and his Overstory attempt have done us the service of demonstrating how difficult it is to build a 2.0 version of for-profit online news chains in Canada, then we owe him a bit of thanks.

We are one more step closer to the place where I feel we must arrive in this country.

Journalism must be recognized to be an embattled public good — profitable or not, a public good essential to the functioning of our democracy.

If it can’t be sustained by distant hedge fund owners or local tech investors, we must creatively imagine, together, other ways to do so.

Ah but we have the CBC, I hear you thinking. Yes, thank goodness we do. But to consider the CBC the solution to all I’ve discussed here is to ignore two things. One, the CBC isn’t everyone’s cup of tea. A truly healthy journalism landscape would be far more diverse than one mothercorp.

And two, we are always one election away from a massive hit to the CBC’s budget. A recent poll showed that nearly half of Canadians strongly or somewhat support defunding the CBC. Defunding the CBC has become a rallying cry of Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre. Without a robust CBC, what is Canada’s plan B?

If in fact there is a war on journalists, so far I have only presented you with a loose bunch of collaborators. Tech barons with strange philosophies. Celebrity pundits subverting fact-based reality. Media owners who are either inept or parasitically destructive. Regulators asleep at the watch.

You might shrug and say OK, journalists don’t have it as good as they used to.

But that seems to be just because digital technologies that people like and invite into their lives have scrambled my neat little diagram of the role journalists should play in a healthy democracy.

Can’t stand in the way of progress Dave!

But this progress is enabling a dangerously reactionary moment around the world. I am speaking of the global assault on democracy fuelled by populist worship of cultish leaders. In Brazil, it was Bolsonaro. In the Philippines, Duterte. In Hungary, Orban. In Russia, the consummate autocrat, Putin.

Our North American prototype is Donald Trump and his Make America Great Again movement. And Donald Trump’s Svengali was Steve Bannon.

In 2012, Bannon famously took over a website called Breitbart when its namesake died and he turned it into a laboratory for fomenting populist anger at the farthest alt-right margins.

Bannon is a massive egotist, but he learns. Here is what Bannon says he learned working in Hong Kong’s online gaming industry in the 2000s. That many men leading dull, unfulfilled lives in the real world not only enjoy creating alternative selves online but the action there actually feels more real to them because the drama, the stakes, feel higher.

It’s a lesson he applied when constructing the comments section of Breitbart.

“This became more of a community than the city they live in, the town they live in, the old bowling league,” he told documentary maker Errol Morris. “The key to these sites was the comment section. This could be weaponized at some point in time. The angry voices, properly directed, have latent political power.”

As we saw happen at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

As a student of the online psyche Bannon co-founded Cambridge Analytica, a company that applied psychological warfare techniques to online campaigning. Eventually the company got into hot water by tapping the personal data of tens of millions of Facebook users without permission.

But not before Bannon’s skills at manipulating public opinion landed him a key role in Trump’s campaign and then as Trump’s chief strategist in the White House — until the two narcissists clashed and Bannon was out.

His next stop was Europe to rally proto-fascist movements and now he broadcasts a streamed online TV show called the War Room that, banned from YouTube, still pumps paranoid lie after lie and hosts the likes of disgraced school shooting denier Alex Jones.

What does Bannon hope to achieve? A former White House colleague of Bannon told Atlantic writer Jennifer Senior that “way too many conversations ended with ‘then we burn it all down… just burn it down.’

“It was never clear as to what ‘it’ was. Congress? The ‘establishment’? Washington, D.C.? The country as he perceived it? The ‘world order’?” the source told Senior.

But if you want to burn it all down, here is what Trump’s master strategist learned is key:

“The Democrats don’t matter,” Bannon told author Michael Lewis in 2018. “The real opposition is the media.

“And the way to deal with them is to flood the zone with shit.”

Now where did Steve Bannon learn that? Well, it’s straight from the totalitarian playbook.

It’s certainly the logic that drives Russian disinformation campaigns, a tactic the U.S. Rand Corp. describes as “a firehose of falsehoods.”

The Russian practitioners themselves call it False Information with a Purpose.

Expert Trygve Olson explains the well-known methods of planting fake conspiracy theories in order to confuse and shatter social cohesion and foster extremists.

The techniques flow from four psychological factors. And here I’m quoting Olson:

“The first is psychological distress — I am worried about... dot dot dot. This distress leads to a desire for answers to explain why. Distress in politics comes as grievances — real or contrived. Either way, people are looking for answers.

“The second is cognitively simplistic answers. Often the solution to problems — whether personal or societal — are complicated. We desire calming answers. Extremism occurs when simple answers to complex problems are offered.

“The third step on the path to extremism is overconfidence. People who become extremists through simple answers become overconfident in their beliefs and explanations. I have the answer — I want to share it with others.”

And here let me interject that disinformation monkey wrenchers exploit this trait by sprinkling the internet with kernels of the false narrative in various real seeming sites and forums — to provide a trail of fake crumbs for the gullible person “doing my own research.”

Back to Olson.

“The fourth phase is intolerance. Those who become extremists have the answers and struggle with those they believe don’t see what they do. Those who don’t are a threat. For the extremist, those who don’t share their beliefs become dangerous — political enemies.”

If ever there was zone designed so that it could flooded with shit, it is the internet.

Faced with this limitless opportunity, it is up to the owners of each platform to decide how much shit to allow to flow. It really comes down to profit. And profit is a function of how the algorithms are tweaked.

Teri Kanefield, an American author, lawyer and sharp observer of internet culture, explains why “people who are monetizing their social media feeds are often the ones writing content that arouses your emotions.”

She notes: “Rage-inducing content helps the content provider by attracting a large audience. It also helps the social media platform by increasing overall engagement. Rage-generators and for-profit social media platforms thus have a common goal: Keep people riled and angry, thus driving polarization and extremism.”

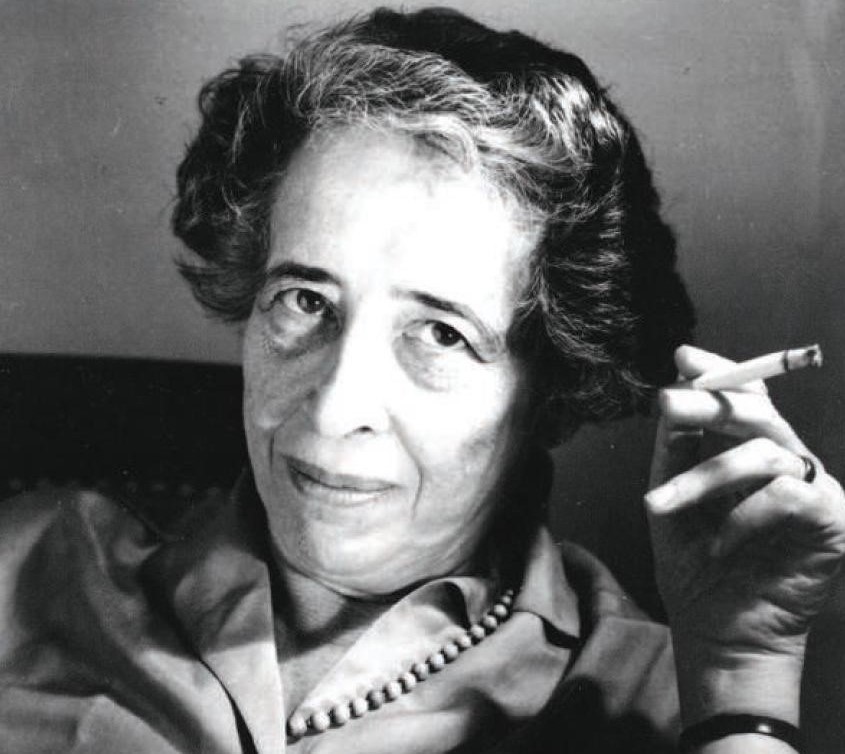

Hannah Arendt, the brilliant 20th century philosopher on the roots of Nazism and other forms of totalitarianism, would recognize this virtual landscape as fertile ground for the rise of movements primed to embrace a cult-like political figure.

Such movements flourish, she said, where citizens feel “atomized, isolated” and have come to despair that existing parties and institutions can render meaning to their lives and imaginations.

They seek a totalizing narrative of transformation and the movement leader provides it.

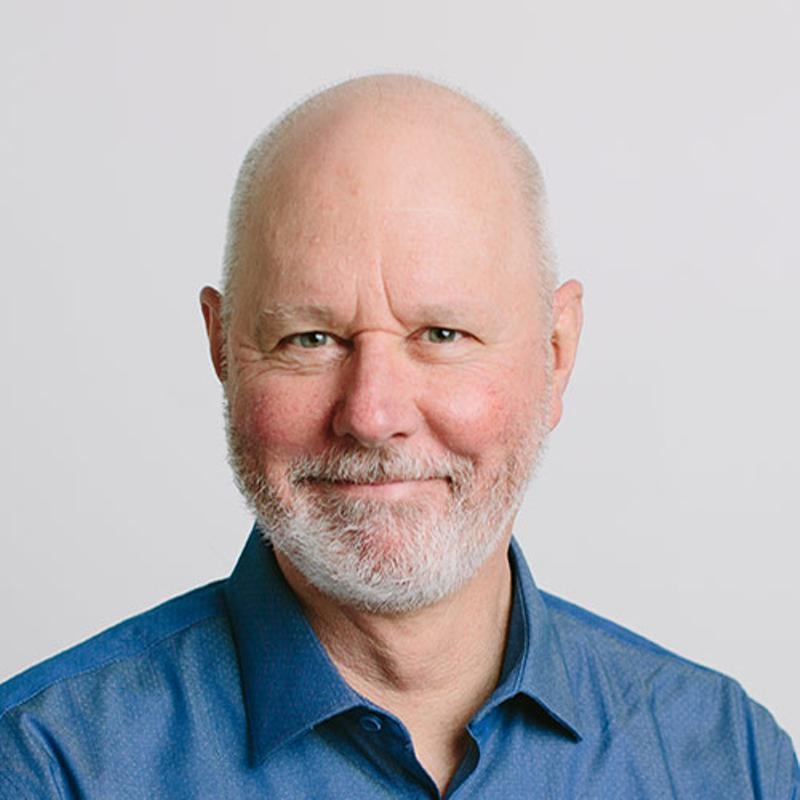

As Arendt scholar Roger Berkowitz writes:

“Movements thrive on the destruction of reality. Because the real world confronts us with challenges and obstructions, reality is uncertain, messy and unsettling. Movements work to create alternate realities that offer adherents a stable and empowering place in the world.

“Amid economic dislocation and the loss of stable identities, the Nazis’ promise of Aryan superiority is stabilizing.... Above all, movements promise consistency.”

And here he quotes Arendt: Such movements “conjure up a lying world of consistency which is more adequate to the needs of the human mind than reality itself.”

Welcome to the endless culture war waged on the internet and cable TV. Its proponents often masquerade as journalists but they are not, by my definition of the craft.

Public interest fact-finding is irrelevant when the goal is to keep pushing emotional buttons in order to maintain a consistent narrative that godless, world dominating socialists are bent on destroying all you hold dear.

Pick your sign of the apocalypse. Is it that the M&Ms have desexualized their cartoon versions of "spokescandies"?

Is it that teaching about slavery in schools is a nefarious plot called Critical Race Theory?

Is there a drag queen, gasp, holding a story time at your local library?

The eruptions are an endless flood of shit calling the lonely, atomized citizen to a war against the "woke."

It is tempting to feel above it all, to consider such debates the preoccupations of small minds.

But journalist and podcaster Sam Adler Bell reminds that the stakes are high. In an essay about how scaremongering about Critical Race Theory fuelled the electoral transformation of many U.S. school boards who are now banning books and supporting broader changes in government, Bell writes:

“For many traditional policy thinkers, the term ‘culture war’ carries a connotation of irrelevance or frivolity: a distraction from more concrete and consequential battles over economic or foreign affairs. But the implication is unearned.

“In 1990, borrowing the phrase from German chancellor Otto Von Bismarck, the American sociologist James Davison Hunter defined ‘culture war’ as ‘competition to define social reality.’ In other words, why are things the way they are?”

Which brings us back Steve Bannon and his aim to “burn it all down.” What was Cambridge Analytica? “This was Steve Bannon’s baby,” said a former contractor named Christopher Wylie turned whistleblower. He called it, “Bannon’s arsenal of weaponry to wage a culture war on America using military strategies.”

What are the spoils of such a war fought to steal from us our reality-based democracy? The reins of tremendous power.

After Trump was elected by narrow margins in two key swing states, a U.S. Senate report revealed that a Russia based outfit called the Internet Research Agency, or IRA, operated thousands of social media accounts interacting with tens of millions of unknowing Americans.

Teri Kanefield relates:

“The IRA even staged real events in the U.S. Using a Facebook page called ‘Heart of Texas’ which had attracted over 250,000 followers, IRA agents organized a ‘Stop Islamization of Texas’ event in 2016 in front of the Islamic Da’wah Center in Houston. At the same time, IRA operatives used their ‘United Muslims for America’ Facebook page with 325,000 followers to promote a second event, to be held at the same time in the same place called ‘Save Islamic Knowledge.’

“Protesters from both sides showed up and, as was the intention of the Russians, violence broke out. The competing events were covered live by local news agencies. They didn’t know both protests had been organized by Russian operators.”

And: “IRA agents posted Biblical verses on a page designed to attract White Evangelicals. White Evangelicals who were attracted to the site believed they were interacting with like-minded Americans. After building their trust, the IRA agents posted lies about Hillary Clinton,” writes Kanefield.

The night Trump’s election was announced, most journalists I know scratched their heads in wonder and dread. The ground clearly had shifted beneath their feet.

It crumbles further with the prospect that an increasingly unhinged Donald Trump, twice impeached, indicted on criminal charges and facing more indictments and law suits, remains the front-runner for the Republican presidential candidate in 2024.

We know the dynamic I have just traced has transformed the political culture of other nations.

Nobel Prize winning Filipino journalist Maria Ressa has said of former strongman President Duterte’s violent crackdowns:

“What happened in the Philippines would not have happened if Facebook wasn’t there. A hundred per cent of Filipinos on the internet are on Facebook. Facebook is our internet.” Lies spread on social media were reinforced by the strongman Duterte in the president’s office, said Ressa. “All of sudden our society was splintering.”

But Canada is different. Canada is immune from such deranged fevers, right? I might be more inclined to agree if we didn’t have the example of Alberta.

In his drive to unite a divided conservative base, Jason Kenney drew from the Trump playbook by constructing a reality-defying threat to Albertans that all could rally against. The conjured enemy was environmentalists who dared suggest the oilsands were major contributors to climate change and energy transition should be a top issue in the province.

He empowered his government officials to bully critics and journalists online. He set up a “war room” to propagandize against oilsands criticism. Among its work — slamming the credibility of the New York Times and calling pernicious an animated children’s film about saving creatures from oil pollution.

Like some Soviet potentate, he set up a tribunal to find environmentalists and their supposed journalist allies guilty of crimes against the state — a boondoggle that fizzled.

He whipped up support among the anti-vaccination crowd by proudly defying the science behind other provinces’ efforts to impose proof of vaccination and further health measures. Predictably, infection rates overwhelmed the province, finally forcing him to act. But pandemics provide plenty of fodder for waging culture war.

John Carlaw, a political scientist at Toronto Metropolitan University terms Jason Kenney’s style “a creative form of authoritarian populist politics.”

We saw where it leads the day last August a Grand Prairie man verbally attacked and intimidated deputy prime minister Chrystia Freeland, who is half his size.

He accused her of being a traitor, and said later he found the experience exhilaratingly satisfying. The episode directly arose, said political scientist Jared Wesley, from right-wing politicians who engage in “rage farming” by advancing false and misleading conspiracy narratives.

“They know how to feed those narratives,” said Wesley, who teaches at the University of Alberta.

What Kenney sowed he reaped in the convoy revolts that blocked his province’s border, and in the loss of his job. He fed a wing of the United Conservative Party that grew and threw him out.

Now it’s led by Danielle Smith, a vaccine skeptic who denies the federal government’s powers over her province enshrined in the constitution.

Everyone in Canada should keep a close eye on the tactics that Smith, building off Kenney, is employing in Alberta.

Unfortunately, there will be fewer journalists in the province to do so. In January a Postmedia internal memo said 12 of its Alberta newspapers would be stopping their print editions and layoffs were coming soon.

Having spent an hour describing the heightening war on reality, what it is like today to be a journalist in the trenches?

What is one’s reward for carrying out the careful, methodical, unglamourous work that I’ve said serious journalism in the public interest entails?

The short answer is that the work has become increasingly dangerous to journalists' mental well-being.

Last year the Canadian Journalism Forum on Violence and Trauma issued a survey-based report called Taking Care. “What we found was an industry struggling to cope with job stress and exposure to trauma."

Here are some its findings:

- Media workers have spent the past two years reporting on the widespread impacts of a deadly virus, all while trying to navigate their own fears, isolation and uncertainties. In return, media workers have become targets to an anti-vaccine movement intent on causing workers personal or professional harm. No media worker was immune from the COVID effect, but some reported greater degrees of stress, including women, people under 50 years old and Asian, Black and Indigenous workers.

- Even before the “freedom convoy” blockades, members of the media were already becoming a lightning rod for harassment and violence. Taking Care data shows that more than half of media workers are targeted, with women, non-binary and trans people, as well as people of colour, reporting alarming rates of harassment and violence.

- Media workers routinely run toward conflict, toiling among the details and graphic imagery of war, murder, sexual violence, humanitarian crises, natural disasters and other crimes and calamities. The fast pace of our work makes it tough to properly process all that we witness on the job.

- Canadian media workers’ overall job satisfaction is high. In spite of the consequences, we are fortified by our mission to inform the public. But we’re only capable of so much — and it’s often our well-being that gets left on the cutting room floor. Just one quarter of Taking Care respondents said their mental well-being was good, with rates of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress and high-risk drinking greatly exceeding Canadian averages.

All good reasons for no one to want to join the ranks of journalists in these difficult times.

And yet. And yet.

While it may surprise you that I’ve intended this talk to be a recruitment appeal, that is why I stand here.

Those of you in the audience who are young and contemplating taking up the craft and life of a journalist dedicated to the public interest, I strongly encourage you to do so.

I can’t promise that conditions will be any better than what I’ve described today. I cannot say that I still believe Martin Luther King’s guarantee that “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

My thoughts about the work journalists do and why have evolved over the 40 years I’ve called myself one.

My inspiration today is the character of Dr. Rieux in the novel The Plague written by Albert Camus.

A mysterious epidemic is sweeping through Rieux’s town, and so his chosen role as a man of medicine takes on all the more urgency.

Why does he expose himself to risk?

Why not abandon the field?

Why does he persist?

His answer resonates with me for its sense of purpose absent a clear path forward. For its humility.

He persists absent the rush of celebrity, the bursts of notoriety that our digital sphere delivers.

He does so absent even the promise of reward in heaven.

Rieux is an agnostic. And he is a doctor. That is his calling. That is his job. And so he says:

“I have no idea what's awaiting me, or what will happen when this all ends. For the moment I know this: there are sick people and they need curing.”

For the moment I know this. Our democracy is vulnerable. And it needs journalists. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: